I: Political Economy

Samuel Hollander's bibliographical essay on David Ricardo highlights the partisan controversies that continue to surround issues of political economy. Political economy transcends narrow economic issues, and investigates the vital interconnections of political, social and ethical concerns in human economic activity.

Our first three summaries are general in scope and theme in order to set the following summaries in a broader context. Telly's lead summary portrays the broad contours of the “classical economic model” in which influential political theorists as well as political economists—as varied as John Locke, Thomas Hobbes, David Ricardo, and John Stuart Mill—developed their ideas. This classical model stressed natural laws, individual freedom, and self-interest. Appleby's article investigates a parallel theme of the relationships between economic ideology and modernization factors. Perkin's following summary questions the opposition, in practice, between individualism and collectivism in nineteenth century socio-political and economic thought.

The following summaries then turn to more specific issues: the industrial revolution in relation to literacy and enclosures; the views of the classical economists, Smith and Ricardo, on such themes as monopoly, money, and wages; and finally, three treatments of the still vexing issue of the causes and effects of inflation, a theme also treated in section III of our summaries.

The Classical Model of Political Economy

Charles S. Telly

University of Dayton School of Law

“The Classical Economic Model and the Nature of Property in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries.” Tulsa Law Journal 13, no. 3 (1978): 406–507.

An important contribution of economics to the idea of freedom has been the development of the so-called “classical economic model.” Although some writers, such as Mark Blaug, have denied the existence of a comprehensive classical model held by all nineteenth century economists, the general outlines of the theory are clear. The classical model assumes the existence of society in which most resources are privately owned. Individuals bargain with each other, and the principal motivation

Edition: current; Page: [37]

each participant is self-interest. Out of these economic interactions, an ordered society will emerge.

As is already apparent, the notion of freedom is crucial to this model. The major theorists in this classical tradition, such as Locke, Smith, and Mill, stressed that the preservation of liberty was an indispensable social precondition. For example, in On Liberty (1859), Mill argues that the function of society is to promote individual autonomy. Each person must be encouraged to assume responsibility for his own life, rather than become dependent on the customs favored by public opinion.

The exponents of the classical model viewed freedom as part of the law of nature. They believed that there were laws of the social world in some ways like the laws discovered by the physical sciences. These natural laws, far from being inconsistent with human freedom, demanded it as their precondition. If each person in society freely acted to promote his own interest, an “invisible hand,” as Adam Smith claimed in the Wealth of Nations and Theory of Moral Sentiments, would operate to transform private good into the general welfare of society.

David Ricardo developed the theme of nature even beyond Smith's exposition. In his economic theory, Ricardo allowed virtually no role for the entrepreneur. Economic law acted in an almost mechanical fashion; the correct working out of the economic processes that Ricardo postulated did not depend on particular entrepreneurial decisions.

The view of human nature professed by the proponents of laissez-faire emphasized self-interest. Perhaps the most striking example of one version of this theory was presented by Thomas Hobbes. In Hobbes's Leviathan (1651), men were not only self-interested but also mutually antagonistic, By contrast, John Locke's view of human nature was substantially more optimistic and harmonious, but he also saw man as egoistically motivated. The Scottish Enlightenment thinker, Frances Hutcheson, however, affirmed a social instinct of human benevolence, a natural feeling of personal sympathy for others. Adam Smith also subscribed to this position and

believed in a natural harmony of interests.

The supporters of the classical model maintained that prices were determined by the market forces. For example, Adam Smith argued that products tended to gravitate around a “natural price,” which was determined by the costs of production. This could not be determined unless the market were allowed to function freely; furthermore, in the short run, supply and demand might cause prices to differ from the natural price.

Wages, under the classical model, were similarly determined by the market. Many followers of the classical model, beginning with John Locke, assumed that wages would tend toward the level of bare subsistence, owing to pressures of population. Smith, Turgot, and Ricardo, among others, each held versions of this “iron law of wages.”

The legacy of the Enlightenment, as expressed in the classical model, may be seen as a modification of the Greek doctrine of natural law. In the classical model, private property was recognized as an individual right This private and individual perspective of rights contrasted with the ancient Greek stress upon the ends of society as a whole.

Edition: current; Page: [38]

Modernization, Ideology, and Economic Freedom

Joyce Appleby

San Diego State University

“Modernization Theory and the Formation of Modern Social Theories in England and America.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 20 (April 1978): 259–285.

Modernization theory has increasingly come to be seen as a failure. Its basic assumption is that societies develop from traditional to modern through evolutionary stages. Traditional societies, in this approach, tend to stress community while modern socieities place more stress upon individualism, self-development, and economic growth. The basic flaw of the theory is that it does not explain how ideology changes as economic development proceeds.

In point of fact, economic development does not uniquely determine a country's ideology. This may be seen by contrasting social thought in England and America during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

The development of England during the seventeenth century was characterized by the rise of a stronger central government and at the same time the prevalence of a greater degree of economic freedom. Economists of the time tended to lavish praise on the benefits of trade. The tendency is especially noteworthy in the writings of Nicholas Barbon and, of course, in the far more widely known John Locke.

After 1689, however, the direction of British social thought changed. The Whig oligarchy in power emphasized national unity and economic growth through state direction. As measures such as the establishment of the Bank of England (1694) became law, the earlier emphasis on the benefits of trade and individualism ended. Writers now reverted to the older balance of trade theory, which stressed the need for a country to accumulate as much gold and silver as possible.

In the American colonies, the situation was different. Here centralized direction of the economy did not become the basis of an ideological movement. Government interferences with trade were bitterly resented, and American writers strongly favored individualism. For example Thomas Paine opposed social hierarchy and favored limited government. He viewed order as arising from individualism, not as something to be centrally imposed.

The contrast between Britain and America shows that economic development is consistent with different ideologies. The simple cause-and-effect relation between them assumed by modernization theory must be rejected.

Individualism vs. Collectivism?

“Individualism Versus Collectivism in Nineteenth Century Britain: A False Antithesis.” Journal of British Studies 17 (Fall 1977): 105–118.

The contrast between individualism and collectivism as themes of social reform and economic thought in nineteenth century Britain is a myth. The contrast was formulated by the great Victorian liberal A.V. Dicey in his influential lectures Law and Opinion (1905). He distinguished three stages in attitudes toward social reform:

Edition: current; Page: [39]

the period of Old Toryism, lasting to 1825 or 1830; the period of Benthamism or Individualism, from 1830 to about 1870; and the post-1870 period of Collectivism. Dicey stressed the role of ideas in accounting for the change from one period to another. Sir William Blackstone was the most influential thinker in the first period, and Jeremy Bentham in the second. Dicey did not single out a singel dominant thinker for the Collectivist period.

Dicey's scheme has been criticized by the so-called Tory or organic school of British institutional history, whose members include Oliver MacDonagh and G. Kitson Clark. They emphasize that reform measures proceeded largely according to the day-to-day activities of persons holding governmental office., not according to the carrying out of ideological aims. Both Dicey and the organic school are wrong: ideology was important, although not all important.

The real mistake of Dicey is to postulate a rigid antithesis between individualism and collectivism. Individualism meant that everyone should be able to pursue his own interests. As such, it was not viewed by most nineteenth-century thinkers as inconsistent with action by the state to protect individuals from exploitation. Specifically, acceptable forms of state intervention included: (1) the prevention of moral nuisances; (2) the enforcement of minimum standards of provision of certain services by some individuals to others (e.g., payment of wages in cash); (3) state financing for the private provision of certain services; (4) direct state provision of a service for part of the population; (5) public provision of a service, on a voluntary basis, for the whole of a population; and (6) the monopoly of essential services by the state (e.g., the telegraph system).

A great gulf stood between these types of collectivism, which most nineteenth-century writers accepted, and the nationalization of the means of production. Few favored this at all. Thus, for all but a few radicals, laissez-fairists, and socialists, there is no real opposition between individualism and collectivism in nineteenth-century Britain.

The Industrial Revolution and Literacy

E. G. West

Carleton University, Ottawa

“Literacy and the Industrial Revolution.” The Economic History Review (August 1978): 369–383.

This article examines the extent and timing of literacy changes in eighteenth and nineteenth century Britain and their relationship to economic growth.

Some British historians contend: (1) that literacy deteriorated during the Industrial Revolution; (2) that growth produces literacy rather than that literacy is a prerequisite of growth (Bowman and Anderson, “Concerning the Role of Education in Development,” in Geertz, ed., Old Societies and New States, New York, 1963, conclude that a literacy rate of 30–40 per cent was a necessary condition for a country to make a significant breakthrough in per capita income); and (3) that the provision of education by private interests was inadequate.

West begins by showing that the relatively high rates of illiteracy recorded in Lancashire were exceptional and were the result of the very high rate of immigration, especially from Ireland, into that county. He also shows, however, that even Lancashire lay within the 30–40 per cent range.

He then goes on to argue that the male literacy rate was stable from about 1740 to 1790 when it began to rise significantly.

Edition: current; Page: [40]

Thus, despite unprecedented population increase from 1760 on, the male literacy rate in England was maintained and before half the “revolution” was over it began to increase. The date of upturn, 1790, marked the beginning also of the large-scale factory system and the widespread commercial use of steam power.

The fact that literacy started to increase as early as 1790 indicates that the means of increasing it had begun to grow too. That implies in turn that private schooling was becoming increasingly available to all classes of the population.

Turning to schooling, as distinct from literacy, West rejects the view that the schools which taught only literacy skills were not well patronized and argues that parents invested “widely and voluntarily” in a type of education which had a literary rather than a practical orientation.

He then proceeds to deal with the contention that the working class was precluded from education in the private schools and had to wait until the authorities provided “free” education. He argues that the evidence suggests that a very high proportion of all children were attending school long before schooling became free and compulsory.

The Forster Education Act was passed in 1870 but it was several years before it had any significant effect on the actual provision of schools and schooling because it took a good deal of time to establish school boards, build schools, etc. Hence its effects could not begin to be felt until well into the 1870s. Yet the evidence strongly suggests that before 1879 something of the order of 90 per cent of the population was literate.

Parliamentary Enclosure and Uprooted Labor

“Enclosure and Labor Supply Revisited.” Explorations in Economic History 15 (April 1978): 172–183.

Did the British government's parliamentary enclosure acts uproot the rural population and thus create an increased supply of labor for industry in early nineteenth century England? Marxian Maurice Dobb argued in Studies in the Development of Capitalism (1946) that the parliamentary enclosures did create a new mobile labor force for “capitalist” industry's needs. On the other hand, since J.D. Chamber's seminal article [“Enclosure and Labour Supply.” Economic History Review 5 (1953): 319–343] the orthodox position has held that the government enclosures did not cause a “real flight from the countryside.”

However, on non-Marxian grounds and through empirical economic analysis of population movements in early nineteenth century England, we have substantial reasons for doubting the orthodox view of Chambers. First, Chambers's evidence is inadequate to maintain that the population increases that occurred in parliamentary enclosed villages were used in rural improvement projects associated with the enclosures, Secondly, Chambers erroneously argued that population grew more rapidly in parliamentary enclosed villages than in other villages possessing common land. And thirdly, at the county level, we find a small but positive association between government enclosure of common land and outmigration.

Edition: current; Page: [41]

Smith's Critique of Monopoly

“The Burdens of Monopoly: Classical Versus Neoclassical.” Southern Economic Journal 44 (April 1978): 829–849.

Whereas in classical analysis a dominant theme is the importance of promoting free trade and eradicating all forms of monopolies, modern neoclassical analysis shows that the actual cost of monopoly is very small. West argues that the modern approach is “too confined” and has become too “institutionally sterile” because it has ignored important elements in the classical critique that are equally pertinent today. Adam Smith's vigorous attack on monopolies provides the starting point of this comparison between classical and neoclassical views of monopoly.

Neoclassical analysis finds that net welfare loss to monopoly is small because most of the effect of higher monopoly price is a redistribution of income to monopolists. Those who challenge this conclusion have centered on rent-seeking activities of those who wish to capture the gain. Classical analysis is much more encompassing in its assessment of the welfare loss to monopoly. Smith specifically pointed both to rent-seeking and attempts to thwart rent-seeking as monopoly losses and also regarded the income redistribution itself as a major loss to monopoly.

Smith's attack on monopolies condemned the state protectionist system of overseas trading companies. These companies, enjoying exclusive trading rights, were subject to diseconomies of scale which included the inefficiencies of large bureaucratic management. Smith identified both the “excessive shirking” and “inadequate monitoring” that has been noted in the modern literature on bureaucracy, and concluded that bad institutions were responsibile for inappropriate employee behavior. One major diseconomy he noted was the tendency for these trading companies to export bureaucracy to the countries they traded with thereby reducing the potential gains from trade. Smith focused particularly on the losses associated with exclusive trading laws with the colonies. He argued that the cost of the monopoly to the public included not only higher prices both in the colonies and the mother country, but also the costs of policing and maintaining the colonies—defending trade routes and maintaining order—and he believed that the loss exceeded the gain.

Although the modern reader may view Smith's tendency to include all restrictions on supply as monopoly as too general for cogent analysis, West points out that Smith should be congratulated for providing a dynamic analysis which included political, constitutional, and legal factors. He was interested in the costs of “monopolizing” as well as the costs of monopoly, and monopolizing behavior will involve the law and constitution as dependent variables. This greatly increases costs of monopoly.

While many of the historical institutions about which Smith was writing have passed, we can still learn from his analysis. Smith reminds us that people use resources to change the rules of the game in their favor, but the rules are “part of the social fabric:” the system of “collective protection of private property” is vulnerable to attempt to close the market. West concludes by pointing to public education as a perfect example of monopolizing behavior which has eliminated the market to such an extent that it is no longer possible to measure the welfare loss.

Edition: current; Page: [42]

Ricardo and the “Dual Development”

“The Reception of Ricardian Economics.” Oxford Economic Papers 29 (July 1977): 221–257.

Many historians of economic thought have argued that the economics of Ricardo was moribund by the 1830s. As a result, economics after this time developed in a dual fashion, split between the Ricardians and their opponents. Both of these contentions exaggerate the extent to which the dissenters rejected Ricardo.

The basic proposition of Ricardo's economics is the inverse relationship between profits and wages (more profits would mean less wages, and vice versa). The wage-rate is taken to be determined from outside the price-system and is measured in terms of a commodity standard of allegedly constant value, such as gold. Increases in wages, according to this view, cannot be inflationary but react only on the rate of profits. Opponents of this approach argue that to consider the wage-rate as determined outside the system is arbitrarily to reduce the number of variables for analysis.

Ricardo's contemporaries, however, did not advance criticisms of this sort against the doctrine. On the contrary, even alleged dissenters against Ricardo's system such as Mountstuart Longfield, Thomas Malthus, and Samuel Bailey all accepted the basic Ricardian doctrine of an inverse wage-profit ratio.

Furthermore, the Ricardian school was much stronger than often pictured. Recent suggestions that J.R. McCulloch was not a full-fledged Ricardian but was more in the tradition of Adam Smith must be rejected. Similarly, Thomas DeQuincey remained a loyal expositor of his mentor, Ricardo.

The members of the supposed dissenting school of anti-Ricardians did not form a united front but often criticized one another much more than they questioned Ricardo. For example, Malthus strongly dissented from many of the propositions of Samuel Bailey. Furthermore, many of their doctrines were consistent with Ricardianism. This is especially the case as regards the long-run determination of wages by supply and demand.

Those who postulate a dual development of nineteenth-century British economics inaccurately place John Stuart Mill in the non-Ricardian camp. Mill regarded himself as someone continuing to develop the insights of Ricardo; to a large extent this could be said of almost all nineteenth-century British economists prior to Mill.

Ricardo on Money

Charles F. Peake

University of Maryland, Baltimore County

“Henry Thorton and the Development of Ricardo's Economic Thought.” History of Political Economy 10 (Summer 1978): 193–212.

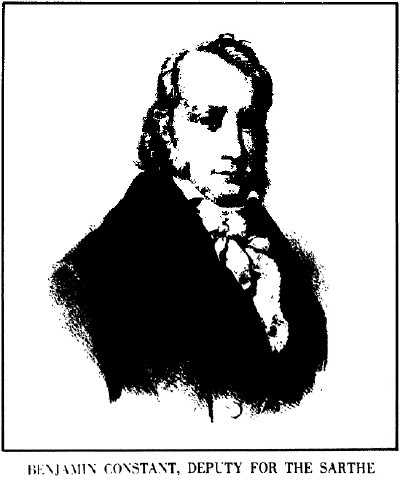

The importance of monetary questions in David Ricardo's economics has frequently been understated. In particular, much of Ricardo's system developed as a response to the monetary theories of Henry Thorton (1760–1815), the English banker and parliamentarian whose book The Paper Credit of Great Britain studied

Edition: current; Page: [43]

the link between the quantity of money, prices, and interest rates.

In 1797, the Bank of England suspended specie payments (that is, payments in gold for bank notes). This policy was defended by the London banker and economist Henry Thornton, who argued that doing so had averted a panic. Thornton's analysis, found in his influential Paper Credit, stressed short-run disequilibrium in the financial market. He favored a discretionary monetary policy, since he believed that this was within the capacity of the Bank of England.

Ricardo in The High Price of Bullion (1810) and Reply to Bosanquet (1811) challenged these contentions. He regarded money as neutral and conducted his analysis in real (commodity) terms. An increase in the money supply could raise only the level of prices; it had no long-run effect on the rate of interest.

When the Bullion Committee was established to reconsider the specie payment question, Ricardo was able to influence Horner and Thornton, who were members of the committee, to adopt his own favorable view of specie resumption. Ricardo, although not the author of the committee's report in 1810, still exerted a powerful influence.

Ricardo continued his interest in monetary questions throughout his life. In particular, the Principles (1817) grew out of his controversy with Thornton and was not simply a response to the debates about Corn Laws. In the Principles, Ricardo continued his sharp separation between the goods and money sectors of the economy.

Inflation and Political Crisis: Germany

“Inflation, Revaluation, and the Crisis of Middle-Class Politics: A Study in the Dissolution of the German Party System, 1923–1928.” Central European History 12 (June 1979): 143–168.

The massive German inflation of the 1920s was one of the main factors responsible for the weakening of the party structure of the Weimar Republic. While both the onset of the 1929 depression and the rise of National Socialism greatly accelerated the dissolution of Germany's bourgeois parties, they did not begin the process but rather continued to intensify factors of disintegration which had been present since the foundation of the Weimar Republic. The established bourgeois parties, such as the German Democratic Party, the German People's Party, and the German National People's Party, proved unable to come up with effective programs to combat the inflation. Instead they tended to dissolve into their constituent social and economic factions.

The inflation proved particularly onerous for those on fixed incomes such as pensioners and for members of the liberal professions. Political controversy over how to handle the inflation intensified after a Supreme Court decision of November, 1923 rejected the principle that “mark equals mark” applied to fulfillment of contracts. That is to say, debts could not be settled for their nominal monetary amount; the discount in value had to be considered. The Cabinet of Cancellor Wilhelm Marx split over how to respond to this decision. One party, headed by Hans Luther, wished to disregard it on the grounds that attempts to recalculate debts would impede economic recovery. Another group wanted to respect the court's decision.

German society was also polarized by

Edition: current; Page: [44]

the issue. Various groups sprang up to agitate for measures in line with special economic interests of various sorts. As the inflation progressed, the position of the bourgeoisie worsened and the party structure became irreparably damaged.

Inflation and Unemployment

Melville J. Ulmer

University of Maryland, College Park

“Old and New Fashions in Employment and Inflation Theory.” Journal of Economic Issues 13 (March 1979): 1–18.

Keynesian economics has proved unable to deal with the increasing rates of inflation prevalent in the U.S. economy. An approach emphasizing microeconomics is needed if the problem of stagflation is to be controlled.

A common occurrence in the history of science is that a widely accepted theory proves unable to cope with new facts. Instead of revising the theory, proponents of the dominant paradigm often deny that essential changes are needed, refusing to confront the challenge which the new data provide. Keynesian economics fits this pattern. Designed to handle the issues of the 1930s depression, it stressed aggregate spending and largely ignored problems of inflation. When inflation was discussed, Keynesian economists dealt with it only in terms of too much spending rather than with particular prices that were too high.

A major problem Keynesian theory is unable to explain concerns the simultaneous existence of inflation and unemployment, popularly termed stagflation. This is not in its origins a recent development and was in fact present in the 1930s and 1940s. Keynesianism finds this difficult to understand, since according to its view, increased spending should generate employment.

One modified Keynesian discussion of these problems has appeared in a recent book by Edmond Malinvaud. He attempts a mathematical derivation of the Keynesian theorems, but his works in large part

reduce to tautologies that ignore the important policy issues. Sidney Weintraub, the author of another recent discussion, is at least aware of the central issues of today. He points out correctly that Keynesian theory assumes that the consumers can anticipate all the effects of inflation, surely a dubious proposition. Weintraub's

Edition: current; Page: [45]

analysis emphasizes wage rates as a cause of inflation, but like Keynesian theory, it overemphasizes macroeconomics.

A better way to combat inflation is to cut out the waste in government programs. Since most unemployed workers are unskilled, we should emphasize programs to provide specifically for this type of worker. Price and wage controls should be applied to industries that are the source of the trouble, not to the entire economy indiscriminately.

Government and Inflation: The McCracken Report

Robert O. Keohane

Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences

“Economics, Inflation, and the Role of the State: Political Implications of the McCracken Report.” World Politics 31 (October 1978): 108–128.

An analysis of the problems of inflation made in the report of an influential committee headed by Paul McCracken poses important issues for democratic government. In 1975 the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) sponsored a committee of eight prominent economists to consider “the recent serious deterioration of economic performance” in the advanced capitalist countries. Their report, Towards Full Employment and Price Stability can be viewed in three dimensions: (1) as explanatory theory; (2) as policy science; and (3) as a set of largely implicit recommendations for political arrangements compatible with modern capitalism.

The main defect of the McCracken Report as an explanatory theory is that it attributes the main economic phenomena it considers to causes which it fails to define adequately. Inflation in recent years, it claims, has to a large extent been caused by political factors. Among these are increases in popular expectations, the development of inflationary expectations, increased union militance, and the growing dependence of the U.S. economy on the international situation. Similarly, the causes of recession, such as a diminished level of public confidence, have a political origin. Yet the authors of the McCracken Report fail to analyze these political causes with sufficient care.

The report's approach to policy science is also questionable. It advocates steady growth, on the grounds that a democratic capitalistic economy cannot endure the inflationary pressures of growth at more extensive rates. This recommendation presupposes that the continuation of capitalism is desirable. This, however, is an ideological assumption which the authors of the McCracken Report ought to have defended explicitly. So far as the report's recommendations for policy are concerned, the authors give no reasons for believing that their slow growth policy has a reasonable chance of being adopted.

II: Concepts of Liberty

Controversy reigns as to the nature, history, and morality of liberty. This set of summaries ranges over a wide diversity of concepts of liberty as analyzed from the perspectives of philosophy, law, history, political philosophy, and psychology. Such interdisciplinary approaches illuminate the relationship of liberty to rights, utilitarianism, individualism, legal doctrines, marriage, women's and children's status. In addition, in these summaries relating to liberty, we witness the dissenting voices of such thinkers in the liberal tradition as Locke, Coke, the American Revolutionaries, Sismondi, Mill, Thoreau, and Szasz, No less illuminating in refining our analysis of freedom are the several non-liberal voices which serve as a counterpoint in the following summaries.

Liberty and Its Components

W. E. Draughton

State University of New York College at Utica/Rome

“Liberty: A Proposed Analysis.” Social Theory and Practice 5 (Fall 1978) 29–44.

In 1955, Harvard scholar Lon L. Fuller observed that “the concept of freedom has been undergoing a progressive deterioration and dissipation of meaning.” Varying definitions of “liberty,” each emphasizing a particular aspect of human experience, have confused and debased this term. We need to revitalize the concept of liberty to solve policy problems.

In formulating his definition, Draughton expressly eliminates the notion of “categorical freedom,” in which a person is either free or not free. Instead, he favors the idea of “comparative freedom” or “degrees of freedom.” This relative view of liberty allows for a large number of interacting components, rather than the single litmus test to determine whether one is free.

One such component is choice. The more alternatives and choices, the more freedom. The notion of “option demand” in urban economics demonstrates that persons are actually willing to pay in order to widen the number of choices to the greatest degree possible. In general, people are more free as the number of acceptable options increases and the number of closed ones diminishes.

Another component in the definition of liberty is utility, which depends directly upon the values of the person who is choosing. In general, a person is more free the greater the positive utility of each open alternative and the smaller the positive utility of each closed alternative. Thus, classic “approach-approach” conflicts are situations of low freedom, since making

Edition: current; Page: [47]

one choice also involves eliminating another choice of high utility. Degrees of utility can serve as a useful measure of the degree of freedom in a situation. Thus, a person faced with a choice of exile or hanging will feel less free than the same person having to choose between being transferred or fired.

The availability of resources (material and nonmaterial) also affect the level of one's freedom. A person making a decision on the basis of insufficient or inaccurate information experiences a limitation of resources directly relevant to his liberty. Mental and physical abilities, health, and monetary resources, all affect one's capacity to carry out decisions.

Social context is also a strong influence upon one's liberty to choose and to act. The socialization process in a particular culture, the benevolence or hostility of persons in one's environment, a precarious or secure outlook for the future—all these social factors influence the individual's faculty of choice.

Professor Draughton envisions extensive policy implications for his comparative concept of freedom. The question of what constitutes a just distribution of liberty arises since freedom now admits of limits. Thus, future public policy will aim at a general raising of the level of liberty and of the justice of its distribution.

Is the Right to Freedom Vacuuous?

“The Rights of Man.” Social Theory and Practice 4 (Spring 1978): 423–444.

The question of how to justify rights, particularly the right to freedom, has puzzled moral philosophy. An analysis of the views of H. L. A. Hart, an influential recent ethician, holds that natural rights, apart from a particular political context, is a vacuous notion.

Edmund Burke strongly opposed the French Revolution's emphasis upon natural rights. He feared that the notion of natural rights might be used as a means of overthrowing government. His fear was groundless. Natural rights mandate no specific policies of government action.

We may see this if we analyze Hart's claim that the basic natural right is the “right to equal freedom.” As Hart points out, we cannot conclude from this right that specific forms of government action are prohibited: the right is only a claim which may be overriden in particular instances. Rights are a “determinable” rather than a “determinate” policy: that is to say, they advance a general claim which must be filled in, in specific instances.

Furthermore, it is not certain that the right to freedom is the most basic right. One cannot have any rights without the right to life, and the notion of rights also seems to presuppose the right to equality of treatment. All of the basic rights seem interconnected.

But again, we cannot deduce any specific course of conduct from them. Rights are better considered as an elaboration and defense of the prudential maxims expressing the aims of particular societies, not truths of all time. Their use is primarily ideological.

Edition: current; Page: [48]

Liberty, Slavery, and Utilitarianism

“What Is Wrong with Slavery?” Philosophy and Public Affairs 8 (Winter 1979): 103–121.

Questions about liberty and its opposite, slavery, raise important issues in moral philosophy. Specifically, utilitarianism has often been criticized on the grounds that it might lead us to conclude that slavery was justifiable. Since everyone knows that slavery is in fact wrong, anti-utilitarians believe that this criticism refutes utilitarianism.

In reply, the method of appealing to people's rights used in the anti-utilitarian criticism is a poor one. The objection appeals to a supposed right not to be enslaved; but claims to rights, unless supported by a general theory, rest only upon particular individuals' intuitions. As such they are in essence arbitrary. If slavery is wrong, this must be shown by demonstrating that it produces more harm than good, i.e., that it is unacceptable on utilitarian grounds.

To settle the question of the harmfulness of slavery, we must first define what constitutes slavery. Two features are relevant: first, slavery is a particular status in society; and second, it rests upon a particular relation to a master. Slavery should be distinguished from serfdom, imprisonment, and military service.

In most cases; slavery will be prohibited on utilitarian grounds, since it clearly harms the slaves. Anti-utilitarians claim, however, that in some cases this would not be so. For example, suppose the welfare of a large number of people depended upon the existence of a small class of slaves. Might not the happiness of the larger number outweigh the onerous consequences to the slaves?

Utilitarians have available two sorts of reply. Moral principles are supposed to apply to cases likely to occur in practice. Thus, our usual principle that slavery is wrong may not fit odd cases, such as the one suggested by the example. Although in this example slavery is morally right, this need not cause us to abandon our usual principle, since people in society would be unable to operate with a complex principle having the form “slavery is wrong—except in cases a, b, c, etc.” People need an easily remembered maxim, and the side that slavery is always wrong best meets the need.

In addition, it is unlikely that, in the example allegedly justifying slavery, all of the consequences have been taken into account. Slavery has damaging psychological effects on both slave and master. When these are taken into consideration, the only instances in which slavery is likely to be justified on utilitarian grounds are those in which it is a necessary means to prevent social chaos.

Individualism, Freedom, and Society

“De l'avenement de l'individu a la decouverte de la société.” Annales 34 (May-June 1979): 451–463.

“In the beginning were individuals, entities sufficient unto themselves, and, later, society, the result of their free association.” This individualist ideology, whereby society represents the willed order of autonomous human beings, has dominated Western social thought (Marxism not excepted) since the eighteenth century. With this new view, Western man effected a radical break with the

Edition: current; Page: [49]

traditionalist concept of social organization—an organic whole ordained by a god or gods in which the individual (even the sovereign) must humbly fulfill his predestined role.

Some social philosophers have viewed the rise of the individual and of the idea of the social contract as a debasement of the Western view of society, a new view based upon what is essentially a myth— that of the autonomous man, unmolded and uncoerced by the social environment that surrounds him. Prof. Gauchet, on the other hand, sees the development of this myth as having created conditions favorable to a much deeper understanding of social processes.

The traditional vision of social organization offers few mysteries to ponder. God's plan is clear, the roles of persons are fixed, and the State acts to preserve divinely ordained harmony on earth. In the eighteenth century, however, a new view evolved whereby the social order maintains itself spontaneously through the free and self-interested actions of autonomous individuals. Nowhere was this concept more evident than in the newly developed science of economics, where countless profit-motivated transactions maintained a stable and harmonious market.

Far from devaluing the importance of society, the market view introduced the notion of invisible social laws which, while operating through the actions of individuals, had positive effects far beyond their intentions and understanding. In effect, the myth of the individual gave birth to the idea of society as a problematical servo-mechanism, whose operations could only be fathomed by serious and toilsome study. It is therefore not surprising that, along with economics, the science of sociology traces its roots back into the eighteenth century. A seeming paradox, the concept of Society grew immeasurably in depth and importance through the evolving ideal of the autonomous individual.

The new conceptualization of social factors also had an unexpected influence on the political element in Western civilization. Once again, the catalyst for this change was the concept of the individual.

The nation-state, a totally original Western contribution to the field of territorial administration, bases itself upon the notion of autonomous and equal citizenunits. In contrast, the traditional state established its legitimacy upon a metaphysical hierarchy of subordination. Nonetheless, the old hierarchical view often acted as a check on the powers of the State. With its demise, there has arisen a vast governmental bureaucracy with virtually unlimited power, whose stated function is to protect the free market and the freedoms of individuals.

The modern state has carefully nurtured the idea that the individual need not submit to an overweening social order. Indeed, it has allowed him the feeling that he is totally autonomous, no longer a member of a social whole. In doing so, however, the State has acquired an administrative hegemony undreamed of in former centuries. Thus, while seemingly freeing themselves from the constraints of social, power, “individuals” have, in fact, become (more than ever) subject to social coercion.

Liberty and Habeas Corpus

“Habeas Corpus and ‘Liberty of the Subject’: Legal Arguments for the Petition of Right in the Parliament of 1628.” The Historian: A Journal of History 41 (February 1979): 257–274.

The debates taking place at the time of the adoption of the Petition of Right in 1628 made an important contribution to individual liberty. Specifically, the arguments of a small group of common lawyers, led by Sir Edward Coke, in the

Edition: current; Page: [50]

House of Commons rested on the assumption that the common law was inviolable. These arguments supporting legally sacrosanct human rights constitute the lasting significance of the 1628 Petition. Although the lawyers' arguments may well have relied on a questionable reading of Magna Carta and other common law precedents, their willingness to stretch the law did not lead them to advance a theory of judicial supremacy in England's government. Rather, they persisted in the traditional view that the rights of subjects and the powers of the Crown were both secured by the common law as reaffirmed by the judiciary.

The immediate occasion for the dispute arose over Darnel's Case, also known as the Five Knight's Case. The knights in question had been imprisoned by special mandate of the king for refusing to consent to a forced loan. Their lawyer, John Selden, claimed that imprisoning them before indictment violated Magna Carta. By such imprisonment, persons might be condemned to “legal death,” languishing in prison indefinitely without ever being brought to trial.

In the parliamentary debates on the bill, Coke and the other common lawyers attempted to tie the privileges, rights, and immunities of Magna Carta to freedom from arbitrary arrest and imprisonment before trial. After the Petition of Right was passed in 1628, the king attempted to circumvent its provisions by requiring high sureties for bail and by refusing defendants the right to be present when their petitions came up for consideration. Although the king imprisoned several members of parliament in 1629, the principles of the Petition of Right were important precedents for later legislation.

Should Britain Have a Bill of Rights?

Howard Levenson

Sollicitor of the Supreme Court of Judicature (U.K.)

“Some Reflections on Civil Liberty in the English Legal System.” American Business Law Journal 7 (Spring 1979): 1–19.

Many American lawyers find it difficult to understand how the British legal system manages to defend civil liberties without a written constitution or Bill of Rights. How could one possibly reverse executive maneuvers or repressive legislation passed by Parliament? The English system does harbor numerous difficulties in defending civil liberties. Varied arguments exist for and against the adoption of a Bill of Rights in the United Kingdom.

Mr. Levenson begins by cataloguing the strategems employed by the British executive in order to circumvent Parliament's supremacy in government. Such ploys have often endangered civil rights in Great Britain. One such maneuver involves creating a climate of hysteria by which the government can secure the agreement of both the House of Commons and Lords to deal with all stages of a bill in one sitting and with no amendments. In such a climate of panic, repressively inclined laws like the Official Secrets Act (1911), the Prevention of Violence Act (1939), and the Prevention of Terrorism Act (1974) were enacted within hours of being introduced.

Another favorite device of the executive is to issue Departmental Circulars which ostensibly establish mere administrative policy. These Circulars are not subject to debate in Parliament, do not enjoy the force of law, and are not binding in the courts. Nonetheless, such directives constitutes a legal precedent which is not easily overturned. For example, the limits of police power and the rights of suspects have been defined by a Home Office Circular called the Judge's Rules and Administrative

Edition: current; Page: [51]

Directions to the Police. Following the issuance of this directive, complaints to the Home Office concerning the admission of illegal evidence in court have often received the bland reply that all suspects are protected by the Judge's Rules. No further investigation ensues.

British performance in due-process measure up poorly against Herbert Packer's four standards for adequately rendered criminal justice: (1) the absence of ex post facto laws, (2) the uniform application of criminal law to all segments of the population, (3) specified limits on the powers of the government to investigate and apprehend suspected criminals, and (4) the presentation of adequate proofs of guilt. Levinson cites celebrated and uncorrected violations of each of these standards. In his view, Great Britain's often cavalier attitude toward civil liberties accounts for her very poor showing in cases brought before the European Human Rights Tribunal.

The question then arises whether civil liberties would be better protected if the United Kingdom enacted a Bill of Rights. Such a proposal has been brought forth both by those concerned with due-process freedom of speech, etc. and by those seeking to protect private property against the ravages of further socialist legislation. It has been further suggested that Britain enact either the United States Charter or the European Convention on Human Rights as a symbol of her commitment to civil liberties on a national as well as international level.

Opponents have pointed out that both these documents have proven inadequate to the task of defending freedom in many areas of human activity. A Bill of Rights would, in addition, constitute a broad grant of power to British judges, who would impose their often narrow, class-oriented views on the whole of the nation. Also, the Bill of Rights might be subject to continual and, at times, arbitrary manipulations by Parliament, rendering it worthless as a legal instrument.

Mr. Levenson concludes that, despite the abuses he enumerates, a Bill of Rights would have a minimal impact on civil liberties in the UNITED Kingdom.

Locke, Women, and Freedom

“Marriage Contract and Social Contract in Seventeenth Century English Political Thought.” Western Political Quarterly 32 (March 1979): 79–91.

John Locke solved an important problem in the political theory of seventeenth-century English liberalism. The idea of liberty involves the view that human beings are free and equal in the state of nature. This view jostled with the fact that almost all social relationships of the time were hierarchical. Specifically, the analogy between political authority and a husband's authority over his wife posed an important problem which Locke solved by developing a new analysis of marriage.

During the English Civil War, the royalist supporters of Charles I such as Sir Dudley Digges appealed against the parliamentarian's claim that their consent to the king's acts was necessary by citing the marriage contract. Once husband and wife consented to be married, the terms of the contract were alleged to come into force irrevocably. These dictated that the husband possessed absolute rights over his wife. In like manner, the king possessed absolute authority over the people of his realm.

Parliamentarians such as Henry Parker and William Bridge tended to counterclaim that there were inherent restrictions

Edition: current; Page: [52]

upon the husband's power. For example, Bridge maintained that if a man committed adultery, his wife had the right to separate from him. The great poet, John Milton, used the analogy of marriage and politics to argue that the political bond of loyalty to the king could be dissolved. Most of the Puritans, however, were limited in the use to which they could put divorce arguments by their own conservative views on marriage.

During the reign of Charles II, James Tyrrell, a liberal writer who was a friend of John Locke's, argued against patriarchal justifications for royal power. He defended a view of marriage based on mutual consent but was ambivalent in his attitude toward women. At times he accepted the conventional view that they were the natural inferiors of men.

A more consistent position on the marriage question was taken by the great theorist John Locke. He denied that there was an analogy between political and familial authority. So far as the latter was concerned, marriage was based on consent, and the parties might agree to virtually any terms they chose. Although there are a few remnants of male supremacy beliefs left in his work, he strikingly anticipated the opinions of later writers favoring female emancipation. This is especially so in his denial of the idea that a woman surrendered control of her property to her husband upon marriage, and in his sympathy for divorce.

Locke, Women, Freedom, and Individualism

Teresa Brennan and Carole Pateman

Macquarie University; University of Sydney

“Mere Auxiliaries to the Commonwealth': Women and the Origins of Liberalism.” Political Studies 27 July 1979): 183–200.

An aspect of freedom neglected by political theorists concerns the place of married women. Individualist political theory, as exemplified in the work of Hobbes and Locke, developed along with the rise of capitalism. Since the position of women worsened during this period, it was relatively easy for Locke (and to a lesser extent Hobbes) to reconcile their individualist premises with a denial of married women's rights.

The problem posed for individualism by the status of married women is clear. Individualist political theory assumes that everyone is free and equal in the state of nature. There is no reason why we should restrict this principle to men. Hobbes, indeed, seems at first sight to accept this consequence. He asserts that the family is an artificial, not a natural, institution, and denies that men are so much more powerful than women in the state of nature that

Edition: current; Page: [53]

they could automatically dominate them. He goes so far as to declare that mothers, not fathers, are the natural lords over babies to whom they have given birth. As Hobbes's theory develops, however, we notice “the problem of the disappearing women.” Hobbes takes for granted that men will be in charge and says almost nothing more about women.

Locke treats the issue much more explicitly. Some have taken him to be an anti-patriarchalist not only toward governmental authority but also toward the husband's authority but also toward the husband's authority in marriage. He states that marriage is founded on consent and at one place grants the wife the right to leave her husband. These appearances are deceiving, because Locke assumed that virtually all women would consent to marriages in which they were subjugated to their husbands. When one considers Locke's very extended notion of tacit consent, it is apparent that his political theory is in practice not very far from the patriarchalist doctrine he is generally taken to be combating.

This aspect of individualism accompanied, and is partially explained by, the worsened position of women under capitalism. Before the 1650s, women had frequently exercised real economic independence and participated in occupations such as brewing on equal terms to men. As capitalist industry grew, it is argued, women fell under the domination of men and their legal position worsened. Although political theory cannot be completely explained by economic trends, it is to a large extent a response to them.

Locke, Property, and Individualism

“John Locke: Between God and Mammon.” Canadian Journal of Political Science 12 (March 1979): 73–96.

Locke's individualism is clarified by exploring his attitude toward work and property. C.B. Macpherson, one of Locke's most influential recent expositors, is correct to stress that Locke favored the accumulation of property. Although a possessive individualist, Locke did not favor unlimited accumulation, however, as Macpherson asserts. Neither did he believe that the poor are irrational. Another important author on Locke, John Dunn, rightly emphasizes Locke's use of the notion of a “calling.” He interprets it in an overly theological way which ignores Locke's secularization of the idea.

Critics of Macpherson have claimed that he ignores Locke's limits to property accumulation. Locke himself withdraws most of these once money has been introduced into an economy. Furthermore, Locke believed that, although natural law was still in effect once society had been instituted, people might voluntarily surrender some of their natural rights in order to promote their prosperity. Thus Macpherson is correct to point out that Locke favored accumulation. He did not believe in unlimited accumulation and in fact condemns it in his writings on education. Macpherson's claim that Locke thought the poor were necessarily irrational is also incorrect. Macpherson tends to dismiss Lock's views on religion, regarding them as having been advanced for the purpose of keeping the poor in check. In point of fact Locke devoted extensive time to his religious works and took them seriously.

John Dunn has strongly emphasized Locke's use of “calling,” According to this idea, people had a particular vocation to pursue their economic tasts as a means of

Edition: current; Page: [54]

advancing their salvation. Dunn tends to ignore the development of a “calling” among the Puritans and understands it in a very strict theological Way. Many of the Puritans themselves secularized the concept of “calling,” placing emphasis on the occupation being pursued more than the mental state of the laborer following the calling. Locke changed this idea even further. He tended to stress worldly success to a great extent, and relegated religion to the realm of a “general calling.” That is to say, Locke tended to distinguish sharply between religious and secular matters. In his concern with both, he can be seen as a transitional figure.

Children, Freedom, and Individualism

Kenneth Henley

Florida International University

“Children and the Individualism of Mill and Nozick.” The Personalist 59 (October 1978): 415–419.

Defining the status of children is a major stumbling block for social systems based on free choice. How does one foster independent judgment on the part of the child? And, to what extent can the choices of the young be termed “free” or “independent?”

Utopian religious communities, like those of the Amish or Shakers, pose special problems in the thorny area of the child's right to choose. Freedom-oriented thinkers value the flourishing of these diverse “experiments of living.” Yet, such groups survive through the strict isolation of all members, including children, from the influences of the larger, pluralistic society. How does one safeguard the child's right to choose his own values, if the social (and particularly educational) setting shields him from alternative ways of living?

John Stuart Mill's responded to this dilemma by exempting children of Utopian communities from compulsory public education, while, at the same time, providing for compulsory state examinations, for which parents would have to prepare their children. The imposition of uniform standards of education upon nonpluralistic groups posed no problems for Mill, since his system provides no room for social experiments which seek coerced adherence to illiberal principles.

A prominent libertarian thinker of our own day, Robert Nozick, does recognize the right of utopian communities to seek intellectual isolation. In his Anarchy, State, and Utopia, Nozick admits that such isolation would limit the child's freedom to know and to choose. However, this difficulty is put aside to be dealt with at a later time.

According to Prof. Henley, both Mill and Nozick ignore the basic question of how socialization effects the person's ability to choose. Every human beingis born as a helpless infant in a society which molds him to have desires appropriate to his place in the community. Education within a certain community exercises profound influence upon the person's character and disposition. The more closed the community, the more profound the influence exercised. Even when presented with a full range of alternatives, a person thus formed would be disposed to make a certain limited number of choices. An Amish girl, raised with the view of women's radical subordination to men, would most likely regard news of her equal rights in the larger society as the erroneous notions of people “out there.”

In Prof. Henley's mind, the basic flaw of the individualist position is its blindness to man's social nature. Individualism

Edition: current; Page: [55]

presupposes a kind of Cartesian consciousness which freely expresses its preferences—unswayed by ingrained social values. This view arises from a fictitious notion of human development.

How then does the individualist reconcile the survival of nonpluralist groups with the child's need for early exposure to alternate values before the community closes his mind to them? To this dilemma, Prof. Henley proposes an admittedly imperfect solution. In Henley's view, the state would have to require pluralistic schools (public or private) whose faculties and student bodies would reflect the diversity of the larger society. In the child of the closed community, such an environment would foster an openness to the possibility of alternatives, while other children could benefit from contact with the utopian child. Socialization in the closed community would, of course, continue but it would be balanced to some extent by these pluralistic contacts.

To implement this solution and to expand the child's ability to choose, more would be needed than Nozick's minimal state or Mill's limited state. Nevertheless, this compromise is necessary in Henley's view, if the individualist is to reconcile freedom of choice (which he values) with the facts of human sociality (which he often ignores).

Liberty and Mental Illness

Michael Nedelsky and Peter Schotten

“Civil Commitment and the Value of Liberty.” Social Research 46 (Summer 1979): 374–397.

A difficult problem in the study of liberty concerns the rights of the mentally ill. Specifically, may persons suffering from treatable mental illnesses be hospitalized against their will? The claim that they can be committed has been challenged on two grounds, especially by Thomas Szasz. First, Szasz contends that the concept of mental illness is a myth. If true, this would rule out involuntary commitment. Second, Szasz argues that to hospitalize someone against his will is incompatible with the ethics of a free society. The authors contend that neither of these arguments can be accepted, and the practice of involuntary commitment is in fact a means of advancing “the vitality of the principle of liberty.”

An objective criterion for mental illness exists if it is defined as a lack of a capacity for rational behavior. The irrationality in question must be gross, i.e., markedly below even minimum standards. Furthermore, the determining factor is not occasional irrational behavior, but the lack of any ability to act rationally. Szasz has objected to this approach on the grounds that there are no objective standards of rationality. To allege that someone is irrational is, on this view, simply to express disapproval of his conduct. Szasz's argument is inconsistent with his practice as a psychiatirst, even if he treats patients only on a voluntary basis. If there are no objective standards, he can be guided by nothing more than his personal preferences. Szasz's objection has nihilistic consequences for psychiatry.

The objective nature of mental illness does not by itself justify voluntary commitment. The practice might be objected to on the grounds that it is inconsistent with liberty to prevent a mentally ill person from acting as he desires, so long as he does not harm others. To this the authors reply that political theory has tended to value liberty as a means to promote human welfare: everyone should be free to pursue the good life as he sees fit. This, however, does not mean that they are unable to act rationally.

Edition: current; Page: [56]

The same answer applies to the claim that liberty cannot be infringed because free inquiry is essential to discover the truth. The process of discussion presupposes rationality. One may, in summary, distinguish between the mentally ill person's desires at the moment and his long-term interests. It is the role of the psychiatrist to help secure the latter, even at the expense of the former.

Sismondi and Liberty

“Sismondi's System of Liberty.” Journal of the History of Ideas 40 (April-June 1979): 251–266.

The cosmopolitan Jean Charles Léonard de Sismondi (1773–1842) is a key transitional thinker between the ancien régime of the eighteenth century and the turbulent social, political, and economic forces of the nineteenth century. As an important late Enlightenment figure, Sismondi sought to preserve and extend human liberty, while correcting its abuses in an era of increasingly mass collective society and growing state intervention against individual initiative. Sismondi's own writings anticipated such reactions to the Enlightenment as romanticism, Historismus, and socialism.

A true cosmopolitan, Sismondi traveled widely from his native Geneva (where he imbibed his ambivalence towards popular sovereignty), and became familiar with French, Italian, Spanish, and British contemporary thought. He was especially influenced by William Robertson and Edward Gibbon. His work on constitutionalism was indebted to Blackstone's Commentaries and Jean Louis Delolme's Constitution de l'Angleterre (1771). Sismondi was lover to Madame de Stael, uncle to Charles Darwin, and teacher of Gian Petro Vieusseux, who was eminent in the Italian risorgimento.

Through his own personal experience with both liberalism and democracy, Sismondi rejected Rousseau's egalitarianism. He believed that such democratic liberty aimed at the sovereignty of an enlightened elite. This needed to be balanced by civic or negative liberty, the area permitting individual freedom of choice. Holding that there were limits to what a legislature could do, Sismondi tended to be skeptical of state-controlled virtue.

Sismondi is noteworthy as a precursor of social science, particularly political sociology. He stressed the influence of constitution and law in determining the character of peoples. A free constitution (a republic or constitutional monarchy as in England) would foster free, educated, virtuous citizens; a despotic constitution would stunt and denature humans. In the field of political sociology three of his most significant contributions are: (1) his analysis of changes in Italians since the end of the Middle Ages (He went beyond constitutional analysis, to discuss the role of religion and customs on national character); (2) his encyclopedia article “Prejudice,” which pioneered in the area of social psychology; and (3) his sympathetic treatment of the proletariat in the Industrial Revolution, a theme which influenced many later writers.

Edition: current; Page: [57]

Mill: On Liberty

Michael Davis

Illinois State University

“The Budget of Tolerance.” Ethics 89 (January 1979): 165–178.

One of the most influential approaches to freedom has been the principle of liberty advanced in John Stuart Mill's On Liberty (1859). Few professed libertarians, however, consistently follow Mill's principle. This fact suggests the need to reexamine Mill's doctrine of tolerance.

Mill distinguished between private acts, which do not harm anyone, and public acts, which do. His thesis is not the trivial proposition that private acts should be left unregulated by the government and by the positive morality of society. Since private acts harm no one, this claim would be universally accepted. Rather, Mill should be taken as arguing that most public acts should be tolerated. An act is defined as “tolerated” if a society's positive morality prohibits it but it is nevertheless protected by the government. The government may protect it either actively, by prohibiting interference with it, or passively, by not taking measures against it.

The wide ranging concept of tolerance Mill favored was supported by an emphasis on the positive value of diversity for society. Although diversity is indeed an important social value, it is argued that, in an unlimited form it can become an evil. Too much change may prove unsettling, both for individuals and societies. The extent to which a society can tolerate changes in its values is determined by its simplicity, stability, and integration.

Four types of libertarian positions may be distinguished according to the way in which liberty and social order are comparatively valued. (1) Extreme libertarians believe that liberty may be restricted only to prohibit direct harm to others. (2) Strong libertarians extend the scope to which liberty may be restricted to include the measures needed to secure a minimum of social order. (3) Classical liberals, including Mill himself, allow restrictions on liberty which aim to insure that a society can develop in which liberty is of value to the individuals composing it. (4) Finally, equalitarian liberals allow the principle of liberty to be limited, as their name suggests, by a principle of equality.

Both liberals and conservatives recognize the need to “budget” liberty. The extent to which liberty should be limited depends to a large degree on the findings of sociology about what is necessary for social order. As such studies are carried further, liberals and conservatives may be expected to find themselves less far apart than they imagined.

Mill, Freedom, and Happiness

James Bogen and Daniel M. Farrell

“Freedom and Happiness in Mill's Defense of Liberty.” Philosophical Quarterly 28 (October 1978): 325–338.

John Stuart Mill's defense of personal freedom in his essay On Liberty has drawn the criticism that it is cogent only in so far as it is not utilitarian. The cornerstone of Mill's argument for individual liberty is the “harm principle”: that we may rightly use power against a person only to prevent harm to others (the person's own physical or moral good does not constitute a sufficient warrant for the use of force. Yet, one could ask how an ethical system based solely on the principle of utility could dissuade

Edition: current; Page: [58]

a member of society from making someone happier than he could make himself when left to his own devices.

Replying to this objection, Mill seems to regard Liberty as an end to be pursued for its own sake. Infringements upon personal freedom would thus constitute the violation of an absolute principle. This, however, would contradict Mill's view (stated in Utilitarianism) that happiness is the only ethical absolute.

The authors assert that this apparent contradiction confuses the meaning of the word “happiness” in Mill's work. Mill abetted this confusion by not clearly distinguishing his two basic uses of the term.

Mill's position becomes a contradictory one if happiness is understood as a simple mental state, consisting of feelings of contentment and well-being. Given this meaning, the pursuit of liberty might indeed conflict with one's happiness—as in the example of the advocates of free speech in the Soviet Union. This simple, monistic view of happiness does in fact appear in Mill's work. However, this notion must not be confused with the idea of happiness as an ethical absolute or as an end in itself. Here, Mill takes a composite view. Happiness consists of various goods such as health, freedom, lack of pain, poetry, etc. These diverse goods are naturally desirable as means to the end of happiness. In Mill's view, however, they are also part of that end, and, as such, they are desirable in and of themselves. Thus, the view that liberty is intrinsically desirable does not contradict the idea that only happiness is to be desired as an end in itself. Happiness is a composite of intrinsically desirable goods.

Nevertheless, this intrinsic view of desirable goods seems to conflict with the essential nature of Mill's utilitarianism, namely that truths are to be discovered within the confines of the contingent world. Mill's defenders have retorted that, when he speaks of various goods as ends in themselves, what he really believes to be desirable as an end is some single, natural principle to which all subsidiary “goods” Pleasure, as a mental state, has often been chosen as the most plausible candidate for this ultimately desirable state.

In fact, Mill does explicitly declare that certain mental states are intrinsically desirable and that all have at least one thing in common: they are all states of happiness or pleasure. That is not to say, however, that only mental states constitute the state of pleasure.

For Mill, pleasure consists not only of the feelings produced by certain activities. It also comprises the objects of these activities and the activities themselves. Thus, in Mill's own words, music, health, poetry, and virtue “are desired and desirable in and for themselves; besides being means, they are part of the end.”

Since the utilitarian good is not monistic, the ranking problems of pluralistic ethical theories immediately arise. For example, is justice or freedom to be more highly prized? In Chapter 4 of Utilitarianism, Mill supplies an embryonic response to this problem. Higher pleasures are to be distinguished from lower ones by “competent judges”—those who have experienced both. Mill's pluralistic ethical position effectively gives the lie to the old charge that utilitarianism, like epicureanism, is a theory fit only for swine.

Freedom of Speech and Moral Development

“Moral Development and Political Thinking: The Case of Freedom of Speech.” Western Political Quarterly 32 (March 1979): 7–20.

Almost all Americans would affirm that they support free speech. However, social science data indicates that the concensus breaks down when the question is asked concretely in terms of deviant groups' right to speak (Nazis, Communists, etc.)

Edition: current; Page: [59]

Reservations are expressed concerning “those with wrong ideas,” “those who talk against churches and religion,” etc.

The upper echelons of society qualify their tolerance of divergent views less so than lower socio-economic classes. Since the educational resources of the elite foster wider opportunities for moral development and since tolerance is a moral activity, researcher Lawrence Kohlberg has theorized that a definite correlation would exist between the level of subjects' moral developmeng and the consistency and quality of their tolerance of free speech.

Kohlberg and his colleagues have carried out a number of experiments with adults to corroborate this thesis. Prof. Patterson, however, has theorized that the process of moral maturation might appear more clearly in children and that correlating their moral development with their level of tolerance would provide a significant and revealing test of the Kohlberg theory.

To evaluate the moral maturity of elementary school pupils, Patterson employed the six-stage scale developed by Kohlberg, who himself followed the research of Jean Piaget. The scale ranges from the “Punishment and Obedience Orientation” in Stage 1 to the “Universal Ethical Principle Orientation” of Stage 6. Individuals pass through the six steps in age-related sequence, and, while rate of development may vary and some individuals may fixate at a certain point, the stage order is never violated. Stage transition is promoted by the individual's discovery of seeming contradictions and inconsistencies in his environment, which he endeavors to resolve.

Patterson further postulated two hypotheses to be tested in his experiments: (1) Since each successive level of moral development constitutes a more adequate mode of resolving moral dilemmas, the higher the stage, the more consistent the application of the principle of free speech; and (2) Those who support free speech in terms of right or principle (a higher level of moral reasoning) will be most tolerant of deviant ideas, and, when asked to provide a possible justification for suppressing deviant expression, those morally advanced subjects would support their justification by lower-level reasoning.

Level of tolerance was tested in two ways. First of all, children were read a series of questions conerning the advisability of free speech. A moral and political dilemma related to free speech was presented along with questions to elicit the child's choice of alternatives and his justification for them. The two tests were found to correlate with each other and, in turn, with the six-stage framework of moral development.

Briefly, moral maturity was found to have a significant relationship to political reasoning. Structures of reasoning about conflict situations were judged by both logical and empirical criteria to correspond to the structures of moral judgement. The research also suggested that the concepts of “tolerance” and “consistency” are far too simple as usually conceptualized, since from stage to stage of moral development, the nature of justification for free speech varies widely. Finally, the experiment throws light on the origins and nature of the quality of tolerance. Prof. Patterson, thus, suggests that Kohlberg's theory may elucidate other aspects of the political process not yet analyzed in the light of moral development.

Freedom in Kant, Hegel, and Marx

“Three Concepts of Freedom: Kant-Hegel-Marx.” Interpretation 7 (January 1978): 27–51.

Kant, Hegel, and Marx are three influential writers on freedom. Though often condemned, their philosophies can be seen in a more favorable light if they are considered as dialectically related to one another.

Edition: current; Page: [60]

Kant's idea of freedom depends upon his distinction between the phenomena of the everyday world and the noumenon, or thing-in-itself. It is only the noumenal self that is free; the empirical self is determined by outward events. Kant's conception wrongly reduces freedom to a purely inner state. One can be free, in his view, even under a despotic government. He believed, however, that one could deduce by pure reason the proper principles of political organization. His ideas on philosophy of law have been very influential.

Hegel criticized Kant's views on freedom for being unhistorical. It is only in society that true freedom can exist. The notion of freedom as arbitrary will most particularly be rejected. Furthermore, freedom develops concretely in history by means of struggle.

The latter theme Marx took up and greatly expanded. He argued that each social system has its own conception of freedom, as determined by the system's economic development. Marx himself, in contrast to his Stalinist disciples, was a strong proponent of freedom of the press. He believed that true freedom could exist only if the state ceased to exist.

Marx, Freedom, and Property

“Freedom and Private Property in Marx.” Philosophy and Public Affairs 8 (Winter 1979): 122–147.

The Communist Manifesto declares: “The theory of Communists may be summed up in the single sentence: Abolition of private property.” Karl Marx's opposition to private ownership remains controversial and ambiguous.

Many analysts of Marxian theory maintain that there is no possibility of a moral critique of capitalism by Marx, since, for him, all moral principles are imminant in the material situation. To the extent, therefore, that capitalism follows bourgeois moral and legal rules, Marx could not condemn private property as unjust or immoral. These analysts have therefore identified the essence of Marx's opposition to private ownership with various economic or historical factors.

On the other hand, some scholars claim that capitalist appropriation of the “surplus value” (or “unpaid labor”) inherent in a product represented for Marx an exploitation of workers. Such exploitation constituted a violation of the moral principle of justice.

Professor Brenkert finds both views in error. Marx based his critique of private property, not on the moral principle of justice, but on the moral principle of freedom.

Edition: current; Page: [61]

Human relations as determined by the bourgeois organization of society negate the value of freedom, as Marx viewed it.

At least three dimensions comprise the freedom that Marx advocates. First of all, one is truly free when one is exempt from fortuity and able to participate in the control of one's affairs. Private ownership, by dividing society into the propertied and the propertyless, denies to the latter the direction of their affairs, stands in opposition to a flourishing and harmonious society, and imposes upon all the clutch of the market's invisible hand.

Secondly, freedom requires the concrete objectification of man through his activities, products, and relations. Capitalism obstructs this objectification by providing for only symbolic interactions between people and things—in terms of exchange-value and money.