Leonard P. Liggio

Editor

John V. Cody

Managing Editor

Suzanne Woods

Production Manager

Ronald Hamowy

Senior Editor

Literature of Liberty, published quarterly by the Institute for Humane Studies, is an interdisciplinary periodical intended to be a resource to the scholarly community. Each issue contains a bibliographical essay and summaries of articles which clarify liberty in the fields of Philosophy, Political Science, Law, Economics, History, Psychology, Sociology, Anthropology, Education, and the Humanities. The summaries are based on articles drawn from approximately four hundred journals published in the United States and abroad. These journals are monitored for Literature of Liberty by the associate editors.

Subscriptions and correspondence should be mailed to Literature of Liberty, 1177 University Drive, Menlo Park, California 94025. The annual subscription rate is $12 (4 issues). Single issues are available for $4 per copy. Overseas rates are $20 for surface mail; $34 for airmail. An annual cumulative index is published in the fourth number of each volume. Second-class postage paid at San Francisco, California, and at additional mailing offices.

©Institute for Humane Studies

ISSN 0161–7303

John E. Bailey, III

Rome, Georgia

Randy Barnett

Chicago, Illinois

William Beach

University of Missouri

Donald Bogie

Georgetown University

Samuel Bostaph

Western Maryland College

M. E. Bradford

University of Dallas

Alfred Cuzan

New Mexico State University

Douglas Den Uyl

Marquette University

Edward C. Facey

Hillsdale College

John N. Gray

Jesus College, Oxford University

Malcolm Greenhill

Oxford University

M. E. Grenander

SUNY at Albany

Walter Grinder

University College, Cork, Ireland

John Hagel

Cambridge, Massachusetts

Jack High

University of California, Los Angeles

Tibor Machan

Reason Foundation, Santa Barbara

William Marina

Florida Atlantic University

Gerald O'Driscoll

New York University

Lyla O'Driscoll

New York Council for the Humanities

David O'Mahony

University College, Cork, Ireland

Ellen Paul

Miami University

Jeffrey Paul

University of Northern Kentucky

Joseph R. Peden

Baruch College, City University of New York

Tommy Rogers

Jackson, Mississippi

Timothy Rogus

Chicago, Illinois

John T. Sanders

Rochester Institute of Technology

Danny Shapiro

University of Minnesota

Sudha Shenoy

University of Newcastle

New South Wales

Bruce Shortt

Harvard Law School

Joseph Stromberg

University of Florida

David Suits

Rochester Institute of Technology

Karen Vaughn

George Mason University

Alan Waterman

Trenton State College

Marty Zupan

Santa Barbara, California

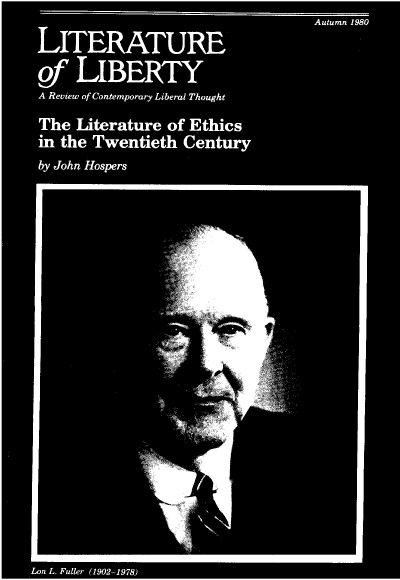

Lon L. Fuller's contributions have been a major milestone in modern moral and legal philosophy. Fuller's approach to legal and moral philosophy seemed to parallel the concepts which Pavia University legal theorist, Bruno Leoni, expressed in his Freedom and the Law (Los Angeles, 1972). Both Fuller and Leoni shared a common emphasis in not identifying legislation with true law; both also searched for fundamental legal principles as exemplified in such expressions of law as common law, custom, private arbitration and spontaneous adjustments among private individuals. Recently, F. A. Hayek has attempted to focus attention on the opposition between law and government statutes.

Fuller rejected coercion and hierarchies of command as identifying characteristics of law (see Fuller's The Morality of Law, 1964). Here also Fuller's attitude appears compatible with Hayek's concept of spontaneous order. Social activities and relations, including economic activities or exchanges, are legitimate and workable only in the context of personal freedom of action and choice. Hayek has emphasized the coordination role performed by individual judgments operating in freedom from statute law. Fuller, likewise, has identified a coordination role as central to human action. Fuller has identified the process of discovery of legal principles expressed in common law, custom, etc., as the natural law tradition. He identified with the system of legal thinking in the natural law tradition because it exemplified man's purposive and aspirational nature, emphasized the role of human reason, and opposed the arbitrariness of governing man. The role of command is excluded from the natural law tradition.

Hayek and Leoni have underscored the analogy between legislation and money. The denationalization or depoliticization of money and of law are seen as comparable processes in harmony with the natural order. The causes of the inflation of money and the inflation of legislation, with the good being depreciated and driven from use by the bad, are envisioned as similar in concept and in practice. The intrusion of government whether into the natural monetary process or the natural legal process creates disorder and depreciates the value of both money and law. Sound money and sound law, resembling sound science and technology, must be based upon a process of discovery and choice and not upon coercion, which is the basis of legislation. In a passage reminiscent of Cicero's stress on the value of the slow, organic growth of Roman law, which is the basis of legislation, Leoni notes:

Legislation appears today to be a quick, rational, and far-reaching remedy against every kind of evil or inconvenience, as compared with, say, judicial decisions, the settlement of disputes by private arbiters, conventions, customs, and similar kinds of spontaneous adjustments on the part of individuals. A fact that almost always goes unnoticed is that a remedy by way of legislation may be too quick to be efficacious, too unpredictably far-reaching to be wholly beneficial, and too directly connected with the contingent views and interests of a handful of people (the Edition: current; Page: [4]legislators), whoever they may be, to be, in fact, a remedy for all concerned. Even when all this is noticed, the criticism is usually directed against particular statutes rather than against legislation as such, and a new remedy is always looked for in “better” statutes instead of in something altogether different from legislation.

Eric A. Havelock, in The Liberal Temper in Greek Politics (1957) indicates the Hellenistic origins of the concept of natural law and of its expression in the idea of liberty as freedom from coercion by other men. Leoni has commented:

The paradoxical situation of our times is that we are governed by men, not, as the classical Aristotelian theory would contend, because we are not governed by laws, but because we are. In this situation it would be of very little use to invoke the law against such men. Machiavelli himself would not have been able to contrive a more ingenious device to dignify the will of a tyrant who pretends to be a simple official acting within the framework of a perfectly legal system. If one values individual freedom of action and decision, one cannot avoid the conclusion that there must be something wrong with the whole system.

Lon Fuller, like Dean Roscoe Pound, has been a leading critic of legal positivism. “Specifically the problem is that of choosing between two competing directions of legal thought which may be labeled natural law and legal positivism. In The Law in Quest of Itself (1940), Fuller wrote that natural law “is the view which denies the possibility of a rigid separation of the is and the ought.” Fuller held that being and value were two aspects of a single reality. Nature or reality contained both an is and an ought. Natural law was discoverable in the process of human activity. F. A. Hayek, in The Rule of Law (Studies in Law, Institute for Humane Studies, 1975) observed:

What all the schools of natural law agree upon is the existence of rules which are not of the deliberate making of any lawgiver. They agree that all positive law derives its validity from some rules that have not in this sense been made by men but which can be “found” and that these rules provide both the criterion for the justice of positive law and the ground for men's obedience to it. Whether they seek the answer in divine inspiration or in the inherent powers of human reason, or in principles which are not themselves part of human reason but constitute non-rational factors that govern the working of the human intellect, or whether they conceive of the natural law as permanent and immutable or as variable in content, they all seek to answer a question which positivism does not recognize. For the latter, law by definition consists exclusively of deliberate commands of a human will.

Hayek's characterization of natural law in opposition to positivism or legal realism finds an interesting analogue in H. L. A. Hart's contrast between two extremes of American jurisprudence, “the Nightmare and the Noble Dream.” For Hart, the “Nightmare” is the view that judges always make and never find the law they impose on litigants. The opposed view of the “Noble Dream” is that the judge never functions as a legislator but rather lives up to Lord Radcliffe's ideal judge: the “objective, impartial, erudite, and experienced declarer of the law.” [See H. L. A. Hart, “American Jurisprudence Through English Eyes: The Nightmare and the Noble Dream.” Georgia Law Review 11 (September 1977): 969–989.]

There have been more articles and books written on ethics in the twentieth century than in the entire history of the subject before 1900. Whether a great deal has been added to the wisdom of the ages by this proliferation of essays, is a matter for individual judgment; but that many distinctions have been made and many concepts clarified that were not made or clarified before, is surely beyond question. For reasons of this very proliferation of studies, the following essay does not attempt to exhaustively survey the entire field of twentieth-century ethics. Some major ethical approaches and “schools”—such as the Continental phenomenological, existential, and realist—are passed over for reasons of space. Our survey will primarily focus on other works in the tradition of Anglo-American ethical analysis.

The great work in ethics which concluded the nineteenth century, a book which many scholars feel is the all-time greatest book ever written on ethics, is Henry Sidgwick's The Methods of Ethics.1 If you want to know what ethical terms are definable and how, or if you desire a clear and worked-out breakdown of the main ethical theories and what can be said for and against each of them; or on a less general level, if you want to know what can be said both in favor of and against laws against prostitution or laws protective of individual privacy, the arguments are all there, laid out with the greatest detail and in a highly systematic manner. No book has ever equaled this one in its thoroughness, scope, and integration of material. The twentieth century may have added new examples or cast fresh light on old ones, but most twentieth-century treatments of ethical issues are incomplete and sketchy compared with Sidgwick's great work. A good introduction to Sidgwick's ethics is contained in C.D. Broad's Five Types of Ethical Theory2 (the last two Edition: current; Page: [6]chapters), and an extended account and evaluation is to be found in Jerome Schneewind's Sidgwick's Ethics and Victorian Moral Philosophy.3

The philosophical background of ethical theory which was most influential on Sidgwick was that of the great eighteenth-century British tradition in ethics: Bishop Butler, Samuel Clarke, Ralph Cudworth, and others. An excellent collection of readings by these eighteenth-century thinkers is Selby-Bigge's anthology, British Moralists.4

Then, in 1903, a book appeared which changed the direction of ethical thinking, G.E. Moore's Principia Ethica.5 Moore's main charge against previous ethical thinkers—all except Sidgwick—was that they had not got the issues straight. John Stuart Mill had defended his utilitarian theory—that the right act was the act which produces the most intrinsically good consequences—without ever making clear whether what he was presenting was a definition of “right” or a statement about right acts: if it was a definition of right, one could object that many acts are believed to be right although they do not produce the best possible consequences in that instance (for example, keeping a promise even though the consequences of breaking it would be better); and if it was a statement about right acts—if we are being told that all right acts also have another characteristic, that they are maximally good-producing—then we do not know how to evaluate the second sentence until we know what the word “right” in it means: to say that one characteristic A always goes along with another characteristic B tells us nothing unless we know what sort of characteristic A is, and this Mill does not tell us. Moore makes similar comments about a whole array of his predecessors in ethical theory. Moore, for his part, held good (but not necessarily “right”) to be indefinable. “Good” was indefinable not in the sense that we could give no synonyms of it (such as “desirable”), but that it was a “simple,” i.e., an unanalyzable concept, like red, for which we could not, in advance, give any verbal instructions which would enable someone to identify it. This is opposed to a “complex” concept, such as horse, for which we could give such instructions, which would enable someone to recognize something as a horse by means of the definition even if that person had never seen a horse.

Moore's book was enormously influential, and the first chapter of Principia Ethica, “The Indefinability of Good,” is to this day reproduced in virtually all of the dozens of anthologies of ethics that have been spawned in the last few decades. Most philosophers do not agree with Moore, but they must come to terms with him. And the Edition: current; Page: [7]effect of his book—not quite what he intended—was to change the entire thrust of ethical thinking for at least a half century in the direction of meta-ethics, which is concerned with the meaning and definability of ethical terms rather than with normative ethics. Normative ethics concerns the discussion of which acts (or classes of acts) are right or wrong, just or unjust, which acts are violation of rights, which are the acts for which a person should be held normally responsible, the relation of acts to motives and intentions and character-traits, all of which had been the traditional subject matter of ethics since classical Greece. The later chapters of Moore's book, dealing with problems of normative ethics, were almost totally neglected in favor of the opening chapter. It is only in the last two decades that normative ethics has again come into its own; but until well after World War II, one could consult the annual index of the principal philosophical magazines—Mind, Philosophical Review, Journal of Philosophy, Ethics, and others—without encountering more than one or two articles on normative ethics in any of them.

To say that a thing is desired is to make a psychological statement about persons; to say that it is desirable is to make a normative statement, namely that it ought to be desired. To say that most persons approve of something, X, is to make a statement about them; but to say that X is right is to say something quite different, which has a consequence (if not part of its meaning) that they ought to approve X. Normative terms occur, of course, in disciplines other than ethics (for example, “beautiful” in aesthetics); but in ethics there occurs an array of normative terms—such as ‘good’, ‘valuable’, ‘desirable’, ‘right’, ‘wrong’, ‘ought’, ‘should’, ‘just’, ‘unjust’, ‘responsible’, and others—which have been the focus of meta-ethical discussion, and an elaborate tracing of their relations to each other. The primary question of meta-ethics, however, is how these terms are related in meaning to non-ethical terms: how ‘desirable’ is related to ‘desired’, how calling an act ‘right’ is related to empirical facts about the act's intentions or consequences, how calling a person (or a motive, or an intention, or a consequence) ‘good’ is related to other data about the person or the consequence. Three main meta-ethical theories have been developed in detail in the twentieth century:

Ethical non-naturalism refers to the view that ethical terms are not analyzable without remainder into non-ethical terms. A proponent of this position may hold that some (or even all) ethical terms are definable by means of other ethical terms (e.g., ‘right’ may be defined as the “act which produces the most good.”); but proponents would further hold that some ethical term, at least one, cannot be Edition: current; Page: [8]defined without remainder by means of non-ethical terms. Thus one cannot escape from the circle of ethical terms. (In just the same manner, mathematical terms, however definable in terms of one another, cannot be defined by means of non-mathematical terms). This residue of meaning is “peculiarly ethical” and not reducible to any combination of empirical or other non-ethical terms.

Moore defended this thesis in the case of ‘good’—at least of ‘good in itself’ or ‘intrinsically good’ (‘instrumentally good’ could be defined as “that which leads to what is intrinsically good”). For example, if someone says (as hedonists do) that pleasure or enjoyment and nothing else is intrinsically good, there is no way to refute him by pointing to empirical facts; one cannot say that this or that empirical feature is good “because that is the very meaning of the term.” Sidgwick had defended the same thesis about ‘right’ in saying that this and other fundamental concepts of ethics are too fundamental to be reducible to any non-ethical concept or combination of such concepts. This thesis was taken up concerning the meaning of ‘right’ in numerous essays, most notably by H.A. Prichard in his famous essay (reprinted almost as often as Moore's Chapter 1) “Does Moral Philosophy Rest on a Mistake?” (1912).6 Prichard argued that no deductive or inductive arguments would establish the truth of an ethical conclusion, and that fundamental ethical truths must be grasped by a direct act of intuition, together with certain safeguards. This position was refined and systematized by Sir David Ross in his extremely influential book, The Right and the Good.7

All forms of ethical naturalism, the second major meta-ethical theory, have in common the thesis that ethical statements about good and right are reducible to statements or sets of statements about the natural world, especially human nature and the human situation. Most famous of the American proponents of ethical naturalism was Ralph Barton Perry, whose books, A General Theory of Value8 and Realms of Value,9 were systematic attempts to defend the view that “value” is definable in terms of psychological concepts such as desiring, willing, striving, enjoying, satisfying and the like, and that moral value (goodness) is a species of value which can be analyzed in terms of the general concept of value itself, as consisting in a preponderance of (positive) value. The Scottish philosopher C.A. Campbell argued a similar thesis on the basis of one concept only, human liking. Campbell distinguished, for example, cooperative from non-cooperative (obstructive) likings (obstructive ones Edition: current; Page: [9]being those that get in the way of other ones, either in the individual or in society as a whole); likings as end vs. as means; integral vs. incidental likings, etc.; and he defined goodness in terms of an array of these distinctions.10 Santayana, Dewey, and Blanshard also presented naturalistic theories.11 (Blanshard: “To say that I ought to do something is ultimately to say that if a set of ends is to be achieved, whose goodness I cannot deny without making nonsense of my own nature, then I must act in a certain way.”) The Ideal Observer theory, another kind of ethical naturalism, holds that an act is right if it would be approved by an ideal observer, one who fulfills certain qualifications such as impartiality; but this view tells us more about the approver than the act which is approved.12 Presumably Ayn Rand's view, that good is proper (appropriate) to the life of man qua man and that “man qua man” can be defined in terms of man's essential rational nature, would also be classified as a naturalistic theory, though she herself does not submit to such classifications.13

Even the theological view that “X is right,” meaning the same as “God commands X,” is a naturalistic view (“supernatural” is the opposite of “natural” in a different meaning of that term), since it defines rightness entirely by means of divine command, and saying that someone commands something involves no ethical term. One consequence of such a view, however, is that if God does not exist, no ethical terms defined in terms of God are intelligible.

Ethical emotivism, the third major meta-ethical theory, is the view that people use ethical terms not to refer to their ostensible objects (people and actions) but to express certain attitudes toward them and to attempt to evoke those attitudes in others. The pure form of the emotive (or non-cognitivist) theory holds that ethical terms do nothing but this, and no question of the truth or falsity of ethical statements arises because the sentences used in uttering them no more express true or false propositions than do commands (“Shut the door!”) or suggestions (“Let's get out of here.”) or questions (“What time is it?”). It is only one function of sentences to express propositions (i.e., to state what is true or false), and ethical sentences actually belong with commands and suggestions rather than with propositions, in spite of the fact that grammatically they look as if they express propositions: “This is square” and “This is good” are grammatically similar, but the first states a proposition (true or false), whereas the second does not. The classic statement of the pure emotive theory is given in Chapter 6 of A.J. Ayer's Language, Edition: current; Page: [10]Truth, and Logic14 (1936), following upon a suggestion contained in an article by Winston F. Barnes,15 and is stated in greater detail in Moritz Schlick's The Problems of Ethics.16

This radical emotivism, however, soon underwent considerable modification. According to the modified emotive theory, ethical sentences do act as expressers and evokers of attitudes: if you say “This would be a good thing to do” and I grant it but do nothing, the intended effect of your utterance on me has not been achieved. (This function of ethical sentences has now become almost universally recognized.) But ethical sentences also convey information: just as “This is a good wrench” conveys information, so does “This is a good man.” And since ethical sentences have cognitive (informational) meaning as well as emotive meaning, the whole question of naturalism vs. non-naturalism arises again with regard to the cognitive component of their meaning. Most modified emotivists are naturalists with regard to the cognitive component, and hold that the reason why ethical sentences are not totally reducible to non-ethical sentences is because of the irreducible nature of the emotive component (“This would be a really fine thing to do” is not the same as “This has qualities A, B, and C”).

In a beautifully clear and coherent exposition C.L. Stevenson introduced the thesis of modified emotivism in his article, “The Emotive Meaning of Ethical Terms,”17 followed by his article “Pursuasive Definitions,”18 and his profound and influential book, Ethics and Language.19 Many modifications of emotivism were introduced into the literature, and the periodical literature of the late '40s and early '50s abounded with them. R.M. Hare's The Language of Morals20 contains a large number of distinctions for clarifying the issue (meaning vs. criteria, description vs. evaluation, commending vs. choosing, etc.). But the most readable and comprehensive statement of this type of view is contained in Patrick Nowell-Smith's Ethics (1954),21 which contains detailed and insightful analyses of “good” in all its major uses, ethical and non-ethical, tapping the literature from Aristotle to the present day, and also presents a plausible account of the meaning of ethical terms in the light of the many distinctions he puts forward. This book remains the most definitive statement of modified emotivism to the present day, and the reading of it renders almost superfluous other treatments of the issue.

The essential truth in emotivism, that ethical language is used not only to state facts but to express attitudes and to persuade others, has been pretty well absorbed into the literature and is no longer a subject of dispute. Whether, minus the emotive component, the language of ethics can be reduced to that of psychology or some Edition: current; Page: [11]other empirical discipline—whether, for example, “I ought to do X” is reducible to some such formulation as “I would feel obliged to do X if I knew all the empirical facts of the case, and if I were impartial, in a rational frame of mind etc.”—is still very much a subject of controversy. But at any rate it is fairly clear that no specific theory of normative ethics (such as Mill's utilitarianism or Kant's categorical imperative) can be derived from any naturalistic analysis, by saying that, for example, “The greatest happiness of the greatest number is what is good because that after all is the very meaning of the word.”

The nature of value, and in what sense value is subjective and in what sense objective (and the difference between “subjective” and “relative”) are thoroughly and systematically discussed in Ralph Barton Perry, General Theory of Value,8 followed by his Realms of Value.9 Many essays have been written on this topic, but it is well summarized in Nicholas Rescher, An Introduction to the Theory of Value,22 together with historical bibliographies, especially in nineteenth-century German philosophy.

The concept of intrinsic goodness (“good for its own sake”) as opposed to instrumental goodness (“good for the same of something else”) is lucidly discussed, together with a defense of a plurality of intrinsic goods, by G.E. Moore in his Ethics,23 Chapter.6, and developed by Brand Blanshard, in Reason & Goodness,24 who concludes that fulfillment and satisfaction are the two intrinsic goods, all others being directly or indirectly reducible to these. The hedonistic notion that pleasure or satisfaction is the only intrinsic good is best stated by Ralph M. Blake in his classic essay, “Why Not Hedonism?”25 That the traditional list of intrinsic goods, e.g., pleasure, happiness, knowledge, virtue, are not intrinsic but relative (not to individuals, but) to human nature, is well defended by C.A. Campbell in “Moral and Non-Moral Values.”10 The entire distinction between intrinsic and instrumental good is attacked by John Dewey, Theory of Valuation,” and by Monroe Beardsley in “Intrinsic Value”.26

That goodness and badness are in some sense objective properties of the things or situations characterized as good or bad, is eloquently defended in the first two sections of Bertrand Russell's classic essay, “The Elements of Ethics” (1912).27 When Russell, after a forty-year absence, returned to writing once more on ethics, in his equally eloquent book, Human Society in Ethics and Politics Edition: current; Page: [12](1955),28 he defended the view that goodness and badness characterize human subjects and not the objects characterized as good and bad. But his actual judgments on particular moral issues changed not at all as a result of this about-face in ethical theory. An excellent book-length discussion of the concepts of moral goodness is G.H. Von Wright, The Varieties of Goodness.29

Psychological egoism, the theory that human beings are all necessarily motivated exclusively by self-interest (if a person does something for another it is only because it makes him feel better to do it than not to do it), is often assumed to be true in psychology, but has been exposed as riddled with logical and methodological errors by philosophers. The best defense of psychological egoism is still that of Moritz Schlick in his book The Problems of Ethics.16

However, the view that people are “wired up” so as always to act out of self-interest has come under extensive attack, and not many philosophers are psychological egoists today, though psychologists and sociologists still are. The view has been attacked on a variety of reasons, principally (1) that it is an unwarranted generalization about human motives (how do you know that all people, everywhere, past and future as well as present, are always egoistically motivated?) and (2) that it is a disguised tautology (if no egoistic motive has been found, we “have faith” that with further investigation it will yet be found, and thus no exceptions to it are permitted). Probably the most thorough systematic treatment of psychological egoism is contained in C.D. Broad's classic essay “Egoism as a Theory of Human Motives.”30 Also worthy of scrutiny are Joel Feinberg's “Psychological Egoism”31 and Alasdair MacIntyre's “Egoism and Altruism.”32

Ethical egoism, unlike psychological egoism, is a substantive view of normative ethics, the view that each person should act in such a way as to promote his or her own self-interest (usually long-term self-interest). Different ethical thinkers have recommended and defended different patterns of life which were supposed to promote one's long-term self-interest. Ethical egoism has a long and distinguished history. The ancient Epicureans were ethical egoists, but held that the pursuit of the “higher pleasures” (primarily intellectual and aesthetic) would lead to personal happiness more than the pursuit of the more easily cultivated “lower pleasures” (food, drink, sex) which they thought would, in the end lead to frustration and unhappiness. The Stoics were on the whole ethical egoists, holding a pessimistic view about the possibilities for personal Edition: current; Page: [13]happiness in a decaying world but recommending apatheia (fortitude and indifference in the face of adverse fortune) as a formula for achieving whatever happiness was possible to man—a theme taken up again with embellishments by the nineteenth-century German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer. Plato was not an ethical egoist, but he was a psychological egoist, and the problem of his Republic was to discover means by which it would become to the self-interest of each person to behave morally toward others, by invoking external sanctions (laws) to make it no longer worth one's while to harm others, as well as internal sanctions (conscience) to induce feelings of guilt at antisocial behavior. Christianity, too, is egoistic, to the extent that it promises rewards for behaving in ways that might not be to one's interest if one considered only one's earthly life.

That ethics in the twentieth century is on the whole antipathetic toward ethical egoism is not so much the result of Immanuel Kant's ethics as that of the eighteenth-century English bishop, Joseph Butler, whose Sermons remain today models of psychological perceptiveness and closely reasoned discourse. But writers on ethics today do not take ethical egoism in the “general” sense the Epicureans did, as an ideal of personal life, but rather as a rigid doctrine to the effect that one should never in any circumstances act contrary to one's own self-interest, and that apart from hope of personal advantage one never has the slightest reason to behave generously toward others—a position that might be called “extreme ethical egoism,” which would have been alien to the Greeks, and was characterized by Hume as the belief that there is no good reason to life one's finger to prevent the fall of a civilization.

Having stated ethical egoism in this extreme form, writers today have a field day knocking it down, before they then pass on to “better things.” A book-length attack on ethical egoism is Thomas Nagel's The Possibility of Altruism.33 It is in the periodical articles, however, that the arguments are most incisively presented, e.g., Richmond Campbell, “A Short Refutation of Ethical Egoism”;34 W.H. Baumer, “Indefensible Impersonal Egoism”;35 G.E. Moore, in Principia Ethica; Donald Emmons, “Refuting the Egoist”;36 J.A. Brunton, “Egoism and Morality”;37 Brian Medlin, “Ultimate Principles and Ethical Egoism.”38 Two brief anthologies are highly recommended as studies of contemporary ethical egoism: David Gauthier (ed.), Morality and Rational Self-Interest,39 and Ronald Milo, Egoism and Altruism.40

The principal barrier to the acceptance of ethical egoism has been the concept of “the moral point of view”—the God's-eye point of view, that of the impartial and omniscient spectator who judges fairly on the basis of the interests of all parties (like a judge in court) Edition: current; Page: [14]rather than the interests of one individual. Ethical egoism, because it recommends action in accordance with the agent's own interest, in thus perceived as outside the pale of morality altogether. The principal author of this view (who, however, takes his cue largely from Kant) is Kurt Baier in his book The Moral Point of View,41 as well as in his article “Moral Reasons.”42 Also of note is Paul Taylor's article “On Taking the Moral Point of View.”43

Nevertheless, ethical egoism has had some defenders. Jesse Kalin is the author of an influential article “In Defense of Egoism,”44 as well as in his article “On Ethical Egoism.”45 The defense of ethical egoism is the subject of book-length treatment by Robert G. OLSON, The Morality of Self-Interest,46 though his view that “the individual is most likely to contribute to social betterment by rationally pursuing his own best long-range interests” could be construed as utilitarian (egoism as a means toward doing what's best for everyone) as much as egoistic. Some objections to ethical egoism are attacked in John Hospers, “Baier and Medlin on Ethical Egoism,”47 and a positive version of ethical egoism is recommended in his “Rule-Egoism.”48 Henry Hazlitt's book The Foundations of Morality49 defends egoism with emphasis on voluntary cooperation as a means of expanding self-interest.

Utilitarianism has taken many forms in the twentieth century. John Stuart Mill defended it in its hedonistic form (“Act so as to maximize happiness”), but Hastings Rashdall in his remarkably fair and insightful book Theory of Good and Evil,50 a classic in normative ethics second only to Sidgwick's Methods of Ethics, stated what he called ‘ideal utilitarianism’: “Act so as to maximize intrinsic good,” leaving open the possibility that other things besides happiness were intrinsically good, thus placing the one controversy in theory of good and the other in theory of right.

“Maximize net expectable utility” has been the basic formulation of utilitarianism—the word “net” indicating that it is not the amount of good that counts but the amount left over after the bad has been considered: thus 10 units of happiness with 5 units of unhappiness is not as good as 6 units of happiness with no unhappiness. “Expectable” indicates that the action to perform is the one that could rationally (on the basis of the evidence available) be expected at the time of acting to produce the most good, not the one that actually did so, something one would have had to be omniscient Edition: current; Page: [15]to know in advance. Thus, if I drive a friend home and have an auto accident on the way, which is not my fault, but in which we both are injured, the act is not wrong, though it would be if one considered only the actual consequences. G.E. Moore's Ethics contains the clearest statement of utilitarianism, minus misleading formulations such as Mill's “greatest happiness of the greatest number,” an ambiguous formula because what produces the greatest total happiness may not produce it for the greatest number. (Jan Narveson's Morality and Utility51 is a thorough and highly recommended discussion of utilitarian ethics.)

A version of utilitarianism that has become current in the last four decades is rule-utilitarianism (so-called, in contrast with the version already discussed, act-utilitarianism). According to rule-utilitarianism, one should act in accordance with the rule of conduct which has the best consequences (highest net expectable utility), not the act which does. For example, finding an innocent scapegoat and sentencing him may stop a crime wave and restore faith in law and order and so on, but it would still be wrong to do this because the rule “Never condemn the known innocent” is a good one, indeed the best one possible in the circumstances, even though there may be exceptional occasions on which the act of letting someone go (a perpetual nuisance, guilty of previous crimes for which he has been let off, etc.) may have better consequences.

A great deal of controversy, however, has attended the status of rule-utilitarianism. Some writers have argued that rule-utilitarianism is reducible to act-utilitarianism. (1) A rule, such as “Never convict those who are known to be innocent,” would be improved from the utilitarian point of view if it were revised to read “Never convict the innocent except when doing so would promote more good than not doing so,” which is exactly what act-utilitarianism would advocate; and the same for any rule of conduct: “Do not break promises once voluntarily made” would become “Do not break promises except when breaking them would do more good than keeping them,” which again is act-utilitarian. (2) To encompass the complexity and individuality of actual situations, one might have to make rules extremely complex, with so many qualifications that each rule would apply to only one situation— in which case doing the “optimic” act (the act with the best consequences) would be identical with following the optimic rule.

There have been numerous attempts to state rule-utilitarianism in such a way as to prevent it from collapsing into act-utilitarianism. Of these attempts the most noteworthy are Jonathan Harrison's “Utilitarianism, Universalization, and Our Duty to Be Just,”52 and Richard Brandt's “Toward a Credible Form Edition: current; Page: [16]of Utilitarianism”53 (making the set of rules short enough to be learnable, andrelativizing them to the culture), but the philosophical literature is full of others. J.J.C. Smart defends act-utilitarianism against rule-utilitarianism in An Outline of a System of Utilitarian Ethics,54 and again later in Smart and Bernard Williams, Utilitarianism: For and Against.55

There are at least three first-rate anthologies of readings on contemporary utilitarianism, which present the issues clearly, juxtaposing readings for and against various utilitarian positions so as to convey an exciting sense of confrontation of ideas: Michael Bayles (ed.), Contemporary Utilitarianism;56 Samuel Gorovitz (ed.), Mill's Utilitarianism: Text and Critical Essays;57 and Thomas Hearn (ed.), Studies in Utilitarianism.58 The many varieties of utilitarianism spawned in the twentieth century are well described and evaluated in David Lyons's comprehensive survey, Forms and Limits of Utilitarianism.59

There are several logical consequences of utilitarianism (of whatever kind) that are sufficiently counter-intuitive to have led moral philosophers to seek not only modifications but the scrapping of the entire theory. Prominent among these are: (1) Aside from the difficulty (impossibility?) of interpersonal utility measurements and comparisons (how do I know that you are experiencing more pleasure or satisfaction than I am?), there is a moral problem which is best brought out in the example of killing. Ordinarily death is preceded by pain and distress, which of course counts as a negative in the utilitarian calculus; but painless death, particularly when one does not dread it because one doesn't know it is going to occur, is not. Thus, if a hundred persons were to be made somewhat happier by one person's death, and if that death were to be painless, and it seemed probable that if he remained alive he would have more unhappiness than happiness for the remainder of his life, it would seem that there is nothing in utilitarianism to prohibit killing him. This theme is developed most thoroughly in Richard Henson, “Utilitarianism and the Wrongness of Killing.”60

(2) Another problem is that utilitarianism is too demanding: it does not make our usual moral distinctions between what is a positive obligation (something it is wrong not to do) with what is permissible (something that it is not wrong to do). “It would be a good thing if you did this” or “It would be wonderful if you did that” is not the same as “It is your duty to do that”—yet according to utilitarianism it is always our duty to maximize utility, and doing anything less than this would be wrong. If a man comes home after a day's work and has a beer in front of his television set, it is surely Edition: current; Page: [17]strange to say he is doing wrong, yet if his one duty is to maximize human welfare there are plenty of other things which he could be doing which would produce more good if he did them. This line of reasoning is forcefully pursued in the final chapter of Gilbert Harman, The Nature of Morality.61

(3) Utilitarianism seems not to take account of the diversity of the sources of obligation. If you agree to pay a boy to mow your lawn and he has done his work and comes to collect his wages, should you pay him only if you can find no more good-producing things to do with your money? (See Richard Brandt, A Theory of the Good and the Right.62)

There is an ambiguity in the word “duty” which is of relevance here. Originally it meant giving what is due (paying your dues, as it were); the presence of something due, such as a return of money borrowed, was always the result of a previous agreement. (See Joel Feinberg, Social Philosophy, p. 63.63) But in the last two centuries the word “duty” has come to mean anything at all which one is morally obliged to do, and in utilitarianism this means maximizing utility. Almost alone among contemporary moral philosophers, the British philosopher C.H. Whiteley (whose works are short and infrequent but always strike the jugular) put forth in his essay “Duties”64 the thesis that duties (in the current sense) always arise through prior agreement and that no man can be charged with any unchosen duties—a thesis rejected by most moral philosophers, and one which, in any case, it is impossible to reconcile with utilitarianism of any stripe.

Closely connected with the topic of rule-utilitarianism is that of utilitarian generalization, whose criterion of action is not “What would be the consequences if I did X?” but “What would be the consequences if everyone did X?” There is some such criterion implicit in certain interpretations of the Golden Rule, though as it stands the Golden Rule is considered by many to contain a serious defect, that its rule of action depends on what a person's desires happen to be: for example, “I should do to others as I wish them to do to me; so I should assist you in your criminal activities because I would wish you to assist me in my criminal activities.” R.M. Hare reinterprets the Golden Rule as a rule of impartiality: a person may make no exceptions on his own behalf: if it's wrong for others to do X, it's wrong for me, and it it's permissible for me to do X, it's permissible for others too (if their situation is similar in relevant respects). This position is amplified and defended in Hare's influential book, Freedom and Reason.65

Edition: current; Page: [18]Kant's Categorical Imperative—“act so that the maxim of your action could become a universal law of human conduct”—contains a reference to generalization, though not of a utilitarian kind because Kant appealed to consistency rather than to consequences: Kant's ethics is not consequentialist, utilitarianism is. An attempt to combine the formalism of Kant with an appeal to utilitarian consequences is outlined in Marcus Singer's article, “Generalization in Ethics,”66 and amplified in detail in his book Generalization in Ethics.67 I should not do X if the consequences of (not my, but) everyone's doing X would be disastrous. But there are numerous counter-intuitive consequences of this position which must be dealt with, and Singer's discussion as well as the many commentaries it has stimulated attempt to deal with them. For example, (1) if everyone refrained from taking up arms, there would be no need for me to do so; but since we live in a world in which violent persons exist, should I ignore this fact and adapt my actions only to the situation in which everyone obeys the rule? Shouldn't one's ethics be geared to the real world rather than an ideal world? But in that case what happens to the generalization test? (2) Often it is perfectly plain that not everyone will do X, and should I do X (follow a good rule) even knowing that many or even most people will not do so? Might not my conformity be an exercise in futility in that case? Yet if I should refrain from following a good rule simply because I know or believe that others will not, many good rules would never be followed, they would never even get off the ground.

These problems have been argued back and forth most fruitfully and challengingly by A.K. Stout in “But Suppose Everyone Did the Same,”68 by A.C. Ewing in “What Would Happen if Everyone Acted like Me?,”69 by Colin Strang in “What if Everyone Did That?,”70 by Kurt Baier in The Moral Point of View,41 and by Don Locke in “The Trivializability of Universalizability.”71

Theories of normative ethics are divided into consequentialist and deontological. Both egoism and utilitarianism are consequentialist theories: in egoism one considers the consequences of the act to oneself, in utilitarianism one considers the consequences of the act to everyone affected by it. But deontological theories are not consequentialist: they do not base the rightness of actions entirely on consequences (they may do so partially), not even rationally expectable consequences.

The ethics of Kant is the purest example of deontological ethics, officially divorced entirely from consequences (though it has been argued that there is a covert appeal to consequences in many of the Edition: current; Page: [19]examples Kant himself gives). Kant's first moral law was the Categorical Imperative: “Act so that the maxim of your action could become a universal law of human conduct.” Some of the logical consequences Kant drew from this—for example, that one is never justified in telling falsehoods—have seemed so implausible that virtually no ethical thinker today accepts this aspect of Kant's ethics without emendation. (If the secret police are trying to find your friend, are you not justified in lying to them so that your friend will not be found?) Kant's second moral law,” Treat every person as an end not as a means,” has been subjected to less criticism by contemporaries, but there is considerable vagueness in what is meant by the phrase “treating someone as an end.” The most thorough-going discussion of this issue is in Respect for Persons by R.S. Downie and Elizabeth Telfer.72

The most systematic defense of Kantian ethics in our century is H.J. Paton, The Categorical Imperative.73 A clear and simple presentation of Kant's ethics is H.B. Acton, Kant's Moral Philosophy.74 A brief but admirably lucid descriptive and critical account is W.D. Ross, Kant's Ethical Theory.75 The best anthology of readings on Kant's ethics is Robert Paul Wolff (ed.), Kant: Foundations of the Metaphysics of Morals, Text and Critical Essays,76 which contains Kant's text as well as some of the best contemporary essays on it.

Trenchant criticisms of central tenets of Kant's ethics are Alasdair MacIntyre, “What Morality is Not,”77 in which the author argues that moral judgments are not necessarily universalizable (saying “I ought to do X” does not imply that anyone in exactly my circumstances ought to do X); and Philippa Foot, “Morality as a System of Hypothetical Imperatives,”78 in which she argues that categorical imperatives are not required in ethics and that hypothetical imperatives (“If you want this, then do that”) can be made to do justice to ethics just as well. Richard Taylor, in his penetrating and perceptive book Good and Evil,79 argues against Kant (1) that general rules are useless in ethics (when they enjoin an act one considers wrong, one simply scraps or amends the rule), and (2) that morality is based not on reason but on man's conative nature (his wants and desires) and that ethics is a matter of adjudicating the conflicting wants of different people.

Most presentations of deontological ethics combine utilitarian with Kantian features. For example, Sir David Ross, in what is probably the most famous and commented-on system of deontological ethics in this century, The Right and the Good,7 does not agree with Kant that it is always wrong to break a promise, but neither does he find utilitarianism correct in believing that whether or not one should keep a promise depends entirely on the good or bad consequences of keeping it. There lies in the fact of having made a promise a prima facie obligation to keep it, and thus the obligation Edition: current; Page: [20]to keep it does not depend solely on the good consequences that ensue from doing so. Ross conceives of a heterogeneous collection of prima facie duties, most of which arise not from the hoped-for benefit of producing certain consequences but from certain events taking place in the past. For example, I have promised a certain person that I will do a certain thing, and the fulfillment of the promise is owed to that person (I did not promise anyone else), and it is because of a past event, my making the promise. There are thus special duties to special people for special reasons, not merely the general duty of beneficence as envisaged by utilitarianism.

There is, for example, (1) the duty of fidelity; if I have made a promise, it would be wrong of me to break it just because I had reason to believe that I might do more good by breaking it (not paying an employee but giving it to charity instead); (2) the duty of reparation, i.e., the duty to make restitution for damages and injuries I have caused; (3) duties of gratitude, to help first those persons (such as parents) who have helped me; (4) duties of justice, to effect a proportionality between reward and desert; and (5) duties of self-improvement, to realize more fully one's own potentialities. Difficult as it is to weight these against each other, they must all be considered in deciding what acts one should perform; no attempt to reduce all these duties to the utilitarian model will suffice, since many of one's duties are (1) past-looking (based on previous acts) rather than future-looking (with an eye only to consequences), and (2) to special people for special reasons rather than to mankind in general.

Ross's highly influential work has led to much discussion and some criticism, particularly about his methodology in arriving at it; but it has largely sufficed to crack any convictions one has about the sufficiency of utilitarianism as the sole means of solving all the problems of normative ethics. But it is only one kind of approach toward breaking the back of utilitarianism. Other deontological views are presented in W. Hudson, Ethical Intuitionism;80 Alan Donagan, The Theory of Morality;81 Alan Gewirth, Reason and Morality;82 A. C. Ewing, Second Thoughts on Moral Philosophy.83

Other approaches consist in an explication and defense of the concepts of justice and rights.

There are occasions when the best consequences (more good for more people) might occur if individuals were treated in certain ways which are called violations of their rights. For example, an innocent person may be convicted in order to stop a crime-wave and restore faith in law and order; persons may be taken to slave labor camps to Edition: current; Page: [21]provide cheap labor for the State where private enterprise is prohibited; crimes may be solved at the expense of bugging and wiretapping and other violations of privacy; a person may be tortured in order to make him reveal classified information. And yet, we are inclined to say, it would be wrong to do these things, i.e., to violate these rights. There is much controversy in contemporary ethics about rights, their basis, their nature, and their scope, and, most of all, what is to be done when they conflict.

Feinberg84 defines a right as a valid claim which one person has against others: if I have a right to my car, I have a valid claim upon you not to use or damage it without my permission. Herbert McCloskey85 defines right in terms of an entitlement: “rights are entitlements to do, have, enjoy, or have done”—whether or not one lays claim to or exercises the right.

There is more disagreement about the basis of rights than about any issue on this topic. (1) Some, such as Gregory Vlastos, hold that the concept of rights is rooted in a conception of universal human worth, as opposed to merits, for the person may have little or no merit and one should still respect his rights because he is a human being. (“If I see a stranger in danger of drowning, I am not likely to ask myself questions about his moral character before going to his aid; my obligation here is to a man, to any man in such circumstances, not to a good man... No one has the right to be cruel to a cruel person. His offense against the moral law has not put him outside the law; he is still protected by its prohibition of cruelty—as much so as are kind persons.”)86 (2) Others base rights on man's rationality; however, some persons appear to be more rational than others, and are they therefore more worthy to have their rights respected? Has a congenital idiot no rights? Some animals appear to be more rational than some people—but much depends on what is meant by the slippery word “rational.” (3) Others have held that the basis of human rights lies in our common human vulnerability, especially our liability to pain and suffering. Since this feature is shared by the animal kingdom, it would appear that animals too have rights. Some persons are more sensitive to pain than others; do they have more rights? And certain forms of treatment which violate rights might cause no pain or suffering at all, such as the painless murder of an innocent man. (4) Or it may be held that “universal respect for human beings is, in a sense, groundless—a kind of ultimate attitude not itself justifiable in more ultimate terms. The parent's unshaken love for the child who has gone bad may not be a response to any merit of the child (he may have none), or to any of his observable qualities... ‘I am his father after all’ may explain to others an affection that might otherwise seem wholly unintelligible, but that does not state a ground for the affection so Edition: current; Page: [22]much as indicate that it is ‘groundless’, but not irrational or mysterious for that.”87

There are various overlapping classifications of rights. There are legal rights which can be claimed in the legal system (which varies from nation to nation and state to state), as opposed to moral rights, those which ought to be upheld by a State even if they are not. There are specific rights, such as your right to collect $100 from me at an agreed upon time if I have borrowed it from you, a right which does not extend to non-lenders, as opposed to general rights, e.g., the right to life and liberty, possessed by everyone because of some feature (not everyone agrees on which) of their common human nature. There are (real or alleged) positive rights, the rights to claim or possess goods and services produced by others (e.g., the right to a minimum standard of living, the right to a paid vacation, the right to decent conditions of work, etc.), as opposed to negative rights, e.g., the right to conduct one's life peacefully and free of aggression, which demand no positive action by others but only forbearance from others in the conduct of one's own activities. There are substantive rights, e.g., rights to liberty and property, as opposed to procedural rights, e.g., the right to a fair trial, the right not to be incarcerated without knowing the nature of the charge against one, which have to do with the procedures by which substantive rights can be implemented or are more likely to be achieved.

Only a few writers, such as Ayn Rand in her essay “Man's Rights,”88 take the position that all rights are negative rights, requiring only non-interference by others rather than positive action. Thus the right to life is the right to conduct one's life according to one's own plan as long as one does it non-coercively, without violating the rights of others. All rights, on this view, are rights to take certain actions, not rights to things; the right to property is not the right to take property but to take such action as is required to earn it. Most writers take the position that each person has a right to certain positive benefits from others, and then the controversy centers around the question of how extensive these benefits shall be, and which of life's goods each person has a right to, especially when granting one good means doing without another. Herbert McCloskey85 argues that each person in the world has a right to the equivalent of three meals a day, decent housing, leisure, etc. To the objection that in some areas it is impossible to produce all this for each person, he replies simply that every person has a right to these things but there is no way (at the moment) to implement this right in practice.

After decades of comparative neglect, the topic of rights is once again in the forefront of ethical controversy. One of the best brief discussions of rights (both legal and moral), which takes no strong Edition: current; Page: [23]position but lists arguments clearly and provides a convenient taxonomy of the subject, is to be found in Joel Feinberg, Social Philosophy, Chapter 4-6. Two short paperback anthologies, which contain some of the clearest and most provocative essays on the concept of rights and problems encountered in trying to adjudicate conflicting rights-claims, are David Lyons (ed.), Rights,89 and Abraham I. Melden, Human Rights.90 Other discussions of various aspects of rights are Alan Gewirth, Reason and Morality,91 A.I. Melden, Rights and Right Conduct,92 and the same author's Rights and Persons.93 In a legal context, see Edmund Cahn, The Great Rights.94

The British philosopher Jonathan Glover defends utilitarianism against all alternatives, even in the face of such arguments about rights as have been summarized here (as well as many others), in a fascinating book, full of examples and case histories, Causing Death and Saving Lives.95 A similar book, not quite so wedded to utilitarianism but equally permeated with thought-provoking examples, is John Mackie, Ethics.96

There is considerable ambiguity in the formulation of specific rights: for example, there is a minimal interpretation of “the right to life,” which interprets it simply as the right not to be murdered: thus a totalitarian dictatorship in which the State owned and totally governed everyone, but did not kill anyone, would respect each individual's right to life according to this interpretation. On the other hand, the maximal interpretation of the right to life construes it as the right to live one's life in accord with one's own voluntary decisions, as long as one does it non-coercively (so as not to interfere with the right to life of others), and in this interpretation the right to life includes other rights such as that of property and freedom of expression.

Property rights have been a subject of controversy ever since John Locke made “mixing one's labor with the land” the basis of property rights in his Second Treatise concerning Civil Government, and Herbert Spencer clarified and expanded some of Locke's points in his Social Statics (1848). But many problems beset property rights, chief among them being how the claims of property are to be adjudicated against other claims: does owning a house give you the right to play loud music and disturb neighbors? to raise poisonous snakes or engage in dangerous activities? to exclude police who are searching for a criminal? to walk about nude even if it offends your neighbors? to build carelessly on a hill so as to endanger houses below in case of rain or mud-slides? and so on endlessly. Perhaps the most careful and judicious of current books on this subject is Laurence Becker, Property Rights.97 A popular brief anthology of readings on property rights is Virginia Held (ed.), Property, Profits, and Economic Justice,98 a group of readings with a collectivist orientation.

Edition: current; Page: [24]Articles on some aspect or other of rights constantly appear in such journals as Ethics and Philosophy and Public Affairs. John Rawls's tremendously popular book, A Theory of Justice,99 lists many thins to which each individual is alleged to have a right, but since some of them work against one another in practice—e.g., the right to liberty and the right to a “reasonable” standard of living—each right is prima facie rather than absolute: for example, the right to liberty is often at odds with the right to “a reasonable standard of living,” since those who do not provide the latter for themselves must receive it at the expense of the earnings of others, thus compromising their liberty. Rawls goes so far as to say that in order to assure the right to welfare for everyone, and to be sure that private individuals and corporations do not exploit the populace, the State should own most of the materials of production. Rawls's book alone has provoked many hundreds of articles and commentaries, including other books such as Brian Barry's The Liberal Theory of Justice,100 which is conceptually acute but complains that Rawls gives too much latitude to individualism! More recently, Ronald Dworkin's celebrated book, Taking Rights Seriously,101 does not take most rights very seriously at all, and is concerned almost exclusively with procedural rights within a judicial system; as far as substantive rights are concerned, his position is difficult to distinguish from utilitarianism. Only Tibor Machan, in his book Human Rights and Human Liberties,102 makes a case for human rights in the pattern of Ayn Rand's “Man's Rights,” although H.L.A. Hart's thesis that there is but one natural right, “the right to be free,”103 could be said to have the same implications.

Closely associated with the issue of rights is that of justice. In a utilitarian calculation, a hundred persons may benefit from the death of one person, and might be justified in putting an end to his life if they benefit sufficiently from his death, and yet such an act would not only be a violation of his right to life, it would be unjust. The two concepts overlap, and one of the five meanings of the term “justice” put forth by Mill in Chapter 5 of his Utilitarianism is a violation of rights. Yet the two concepts are different: rights are like a no-trespassing sign beyond which one may not go in his treatment of other human beings; justice has the connotation of fairness, and many acts and situations can be unfair without violating a person's rights, such as leaving one of your children unprovided for in your will and leaving everything to the other child.

In dealing with justice, it is important to distinguish individual justice from comparative justice. Individual justice is the apportionment of treatment to desert, already discussed. Comparative Edition: current; Page: [25]justice is not collective justice as might be supposed; “collective justice” is a contradiction in terms, since justice is by its nature individualistic: if a person has been unjustly treated it is no mitigation of the injustice that other members of his race or class or club have been justly treated. Comparative justice is justice in treatment in relation to others: thus, if one person has received the penalty he deserved for an offense, but two other persons who committed the same offense have been let off, his treatment is still just (since he got what he deserved) but unjust in relation to theirs, since they were unjustly let off. Feinberg's treatment of justice (Chapter 7 of Social Philosophy) brings out this and other distinctions in the concept of justice with great clarity. See also Otto Bird, The Idea of Justice.104

The central concept of justice is that of treatment in accord with desert. Just punishment is getting the punishment one deserves, just reward is getting the reward one deserves. There are different views of what one deserves, of course, and thus different persons would disagree on whether a specific act or outcome was just, not because they disagreed with the definition of justice, but because they have a different concept of which outcomes are deserved. Some would say for example, that the only criterion of a just wage is (1) the degree of achievement in it, just as grades in courses are measured; some say that a more proper criterion is that of (2) amount of effort expended, regardless of how much is achieved by that effort; some say that the proper criterion is (3) equality—that all distributions should be equal regardless of the amount of effort or achievement (in spite of Aristotle's dictum that justice consists in rewarding equals equally and unequals unequally); some even say that deserts should be based on (4) need, as a supplement to or a substitute for the previous criteria (or, sometimes, that justice consists in fulfilling needs, and has nothing to do with desert).

In a free-market system, of course, wages must be based on achievement: those who need a job most are those likely to be least equipped to fulfill it; if everyone received equal wages there would be no motivation to rise or to do well (Edward Bellamy's nineteenth-century classic Looking Backward to the contrary notwithstanding); and if wages were based on effort, those who could with great effort type 5 words a minute would receive higher wages than those who could do 90 words a minute with ease. But most contemporary writers on justice allow the free market only a very limited scope.

The most influential contemporary book on justice is John Rawls's A Theory of Justice.99 In addition to the limitations on the free market previously mentioned in discussing Rawls, the operations of the market are to be constrained by the “maximin principle,” according to which any innovations, such as an invention, might not be instituted or permitted to exist if anyone whatever is the worse off for it: it must benefit the “least advantaged persons” in Edition: current; Page: [26]society along with the persons involved in inventing it. Thus the automobile should benefit even the buggy manufacturer whose profession was replaced by the invention of the automobile. One wonders how many useful innovations in a society would pass that requirement. Nor is it ever discussed how the “least advantaged” came to be so—whether through no fault of their own, or through spending beyond their income, etc.—an important point which is carefully discussed in Herbert Spencer's The Man vs. the State in 1884.

Rawls's is a contract theory of justice: society is to be governed by such rules as would be agreed on by everyone in advance of knowing his or her particular position in it (“the veil of ignorance”) Thus no one would vote for racist legislation from behind the veil of ignorance, since he might turn out to belong to the race that was legislated into inferiority, nor would he favor anti-labor legislation because he might turn out to be a laborer, and so on. The veil of ignorance device is apparently designed to guarantee impartiality, but one could speculate on what is left of this hypothetical voter once he is ignorant of not only the particular facts of his situation, but the sex and race he belongs to, the era in which he lives, and the temperament he has.

There have been many hundreds of reviews and commentaries on Rawls's work. The clearest and most thorough is that of R.M. Hare in a two-piece article in the Philosophical Quarterly.105 Brian Barry's The Liberal Theory of Justice100 is the most comprehensive book-length analysis of Rawls's work. The most incisive criticism is by Wallace Matson, “What Rawls Calls Justice.”106 Most of his critics would impose more rather than fewer restrictions on the operations of the market than Rawls does.

A pair of influential books on justice in a distributive context are by Nicholas Rescher,107 Distributive Justice109 and Welfare.108 Rescher argues the insufficiency of utilitarianism: first of all, because the greatest welfare may accrue to the smallest number (utilitarianism contains no principle of distribution); second, a utility “floor” is needed—there should be a minimum of material welfare below which no one is permitted to go; third, each person's share in a utilitarianism has nothing to do with desert, since desert is a “past-looking” concept based on past performance and not future potential, and utilitarianism looks only to maximizing good future consequences. The upshot of his discussion is not all that different from Rawls's, though it is arrived at by quite a different route; at any rate, the recommended interventions in the operation of the free market are as numerous in Rescher as in Rawls. In both cases the discussion is primarily concerned with how wealth is to be distributed, with no mention whatever of how it is to be produced; nor is any moral question raised about the legitimacy of transferring wealth from producers to non-producers without the producers' consent.

Edition: current; Page: [27]The free market as a mechanism for achieving justice is almost, but not quite, ignored in the literature. The most remarkable chapter of F.A. Hayek's The Constitution of Liberty,109 “Equality, Merit, and Value,” defends the justice of the free-market system, justifying the fact that in a free market we trade with others on the basis of what they produce that we desire to have, rather than on their moral merit or degree of effort expended in doing so. Defending the free market also are two essays, “Welfare and Government”110 and “Free Enterprise as the Embodiment of Justice,”111 both by John Hospers; and Irving Kristol treats capitalism favorably in his discussion of justice.112 Far more influential in academic circles, however, are books such as Norman Bowie's Toward a New Theory of Distributive Justice,113 in which the demands of justice are not satisfied by anything short of a full-fledged socialist state. In Michael Bayles's recent book Principles of Legislation,114 the laws regulating the market are so all-pervasive that it is doubtful whether a market economy could long survive all the recommended restrictions. Perhaps the most extreme example of all is an article by Kai Nielsen, “On Justifying Revolution,”115 in which the author argues that (1) The U.S. is a capitalist nation, (2) capitalism means exploitation of the poor by the rich, (3) the power of the state must be invoked to correct this situation and turn the U.S. into a just (Marxian) society, and (4) if this is not done quickly, violent revolution is called for to overthrow the capitalists, by assassination if necessary.

The concept of equality is customarily treated together with that of justice. But equality must be equality of something: equality of income, equality of happiness or pain, equality of opportunity, etc. The only kind of equality embedded in the American political structure is that of “equality before the law”: e.g., if two persons are convicted of equal offenses (including all the conditions, such as motivation and extenuating circumstances) there should be equal penalties—one person should not be treated differently from another because of his race or creed, or because he is a friend or relative of the judge, or for other reasons that have nothing to do with the merits of the case.

The principal focus of discussions of equality in the latter half of the twentieth century, however, is not equality before the law (its truth is taken for granted) but rather (1) equality of income and (2) equality of opportunity. There are problems, however, with both of these. To maintain equality of income would require such a constant process of enforcement (taking away from those who had worked harder or made wise investments, to give to those who had not) that a full-fledged police state would almost necessarily be the result. Moreover, before long all incentive would disappear and what Edition: current; Page: [28]would be left would be equality of poverty, or “splendidly equalized destitution.” Equality of opportunity is a more plausible goal; yet if complete equality of opportunity is demanded, and not merely a chance to achieve, it too would require not only extensive legislation calling for enforced redistribution of income, but ultimately also the abolition of the family, for as long as some children have parents who provide a congenial atmosphere for their development and others have parents who do not, an inequality of opportunity results which is far greater than any inequality that is brought about by unequal incomes.

The best book-length treatment of the concept of equality is John Wilson's Equality.116 A popular current paperback anthology on the subject, particularly in the context of government “affirmative action” programs, is Equality and Preferential Treatment, edited by Marshall Cohen, Thomas Nagel, and Thomas Scanlon.117 The most conceptually penetrating, as well as fair and balanced, pair of essays on the subject (published together), both entitled “Equality,” are by Richard Wollheim and Isaiah Berlin.118 Thrusting in the direction of equality of income for everyone regardless of merit or qualifications are Bernard Williams, “the Idea of Equality,”119 and Hugo Bedau, “Radical Egalitarianism.”120 A powerful counterargument to these pieces is contained in two trenchant essays by the British philosopher J.R. Lucas, “Against Equality”121 and “Against Equality Again,”122 as well as in an equally rousing piece by another British philosopher, Antony Flew, “Justice or Equality?”123

The most controversial application of the concepts of utility, rights, and justice occurs in the theory of punishment. When a legal offense has been committed, what considerations are to determine what punishment, if any, should be meted out to the offender, and what general criteria are to be used for such a determination?

The most time-honored view of punishment, as well as apparently the one most deeply rooted in human nature, is the retributive. Retribution need not mean “an eye for an eye”; it need not imply any view about the punishment being similar to, or a mirror-image of, the crime—these are special twists that have been attached historically to the retributive view. All that is essential to the retributive (or deserts) theory of punishment is that (1) punishment is because of, not in order to—in other words, what justifies punishing is a misdeed committed in the past, and that (2) punishment should be in accord with desert (in other words, it should be just). First and Edition: current; Page: [29]foremost, a judge pronounces a sentence because the person has been convicted of a crime, not in order to improve the prisoner or society. Lucid defenses of the retributive view in the twentieth century include: W.D. Mabbott, “Punishment”;124 C.S. Lewis, “The Humanitarian Theory of Punishment”;125 H.J. McCloskey, “A Non-utilitarian Approach to Punishment,”126 Herbert Morris, “Persons and Punishment.”127

A more modern and allegedly enlightened view of punishment is the utilitarian: according to this view, the purpose of punishing is to do some good—the past cannot be changed, and it is immoral to punish if no good can come of such action. The good to be achieved (or evil to be avoided) by punishing, however, falls in different ways upon different groups: (1) there is good to be achieved for the offender, namely rehabilitation; (2) the good of potential or would-be offenders, namely deterrence; (3) the good of society in general, namely protection against criminals. Some writers call this the deterrence theory of punishment, though deterrence is only one facet of the utilitarian theory of punishment. Moreover, some of these factors work against others: a murderer is more likely to be a model prisoner than a petty thief is, and society is less endangered by a one-time killer who has no impulse to repeat his act than by a recurring minor trouble-maker. Punishing him may deter others but will neither rehabilitate him (since he needs no rehabilitation) nor protect others (because they need no protection from him). Moreover, to the extent that deterrence is a goal of punishing, it can often be accomplished just as well by punishing the wrong person instead of the right one: punishing an innocent scapegoat can stop a crime wave and restore people's faith in law and order.

A common utilitarian recommendation, treating a prisoner psychiatrically rather than imprisoning him, sounds humane but has seldom had favorable results in practice. This is not only because most criminals are not greatly helped by attempts at psychiatric treatment, but because the psychiatrist in charge is in a position to play God with other people's lives, moulding them into his image of what they should be and refusing to release them until his aims for them have been achieved. And if treatment is continued until “cure” is pronounced, the sentence can be indeterminate: a person convicted of petty theft may be incarcerated for years under conditions of coercive “therapy” so severe that he would prefer a determinate prison sentence to indeterminate treatment. (See Jessica Mitford, Kind and Usual Punishment.128)

Most sociologists and penologists tend to be utilitarians with regard to punishment, and to assume the truth of utilitarianism as Edition: current; Page: [30]axiomatic rather than arguing for it. Defenses of the utilitarian theory of punishment include: Robert Waelder, “Psychiatry and the Problem of Criminal Responsibility,”129 advocating “complete elimination of the concept of retribution”; Bertrand Russell, Roads to Freedom;130 B.F. Skinner, Science and Human Behavior;131 and Karl Menninger, “Therapy, Not Punishment.”132