THE HISTORY OF THE DECLINE AND FALL OF THE ROMAN EMPIRE

CHAPTER XXXIV

The Character, Conquests, and Court of Attila, King of the Huns — Death of Theodosius the Younger — Elevation of Marcian to the Empire of the East

The Western world was oppressed by the Goths and Vandals, who fled before the Huns; but the achievements of the Huns themselves were not adequate to their power and prosperity. Their victorious hordes had spread from the Volga to the Danube; but the public force was exhausted by the discord of independent chieftains; their valour was idly consumed in obscure and predatory excursions; and they often degraded their national dignity by condescending, for the hopes of spoil, to enlist under the banners of their fugitive enemies. In the reign of Attila, the Huns again became the terror of the world; and I shall now describe the character and actions of that formidable Barbarian, who Edition: current; Page: [2] alternately insulted and invaded the East and the West, and urged the rapid downfall of the Roman empire.

In the tide of emigration which impetuously rolled from the confines of China to those of Germany, the most powerful and populous tribes may commonly be found on the verge of the Roman provinces. The accumulated weight was sustained for a while by artificial barriers; and the easy condescension of the emperors invited, without satisfying, the insolent demands of the Barbarians, who had acquired an eager appetite for the luxuries of civilised life. The Hungarians, who ambitiously insert the name of Attila among their native kings, may affirm with truth that the hordes which were subject to his uncle Roas, or Rugilas, had formed their encampments within the limits of modern Hungary, in a fertile country which liberally supplied the wants of a nation of hunters and shepherds. In this advantageous situation, Rugilas and his valiant brothers, who continually added to their power and reputation, commanded the alternative of peace or war with the two empires. His alliance with the Romans of the West was cemented by his personal friendship for the great Aetius; who was always secure of finding in the Barbarian camp a hospitable reception and a powerful support. At his solicitation, in the name of John the usurper, sixty thousand Huns advanced to the confines of Italy; their march and their retreat were alike expensive to the state; and the grateful policy of Aetius abandoned the possession of Pannonia to his faithful confederates. The Romans of the East were not less apprehensive of the arms of Rugilas, which threatened the provinces, or even the Edition: current; Page: [3] capital. Some ecclesiastical historians have destroyed the Barbarians with lightning and pestilence; but Theodosius was reduced to the more humble expedient of stipulating an annual payment of three hundred and fifty pounds of gold, and of disguising this dishonourable tribute by the title of general, which the king of the Huns condescended to accept. The public tranquillity was frequently interrupted by the fierce impatience of the Barbarians and the perfidious intrigues of the Byzantine court. Four dependent nations, among whom we may distinguish the Bavarians, disclaimed the sovereignty of the Huns; and their revolt was encouraged and protected by a Roman alliance; till the just claims and formidable power of Rugilas were effectually urged by the voice of Eslaw, his ambassador. Peace was the unanimous wish of the senate; their decree was ratified by the emperor; and two ambassadors were named, Plinthas, a general of Scythian extraction, but of consular rank, and the quæstor Epigenes, a wise and experienced statesman, who was recommended to that office by his ambitious colleague.

The death of Rugilas suspended the progress of the treaty. His two nephews, Attila and Bleda, who succeeded to the throne of their uncle, consented to a personal interview with the ambassadors of Constantinople; but, as they proudly refused to dismount, the business was transacted on horseback, in a spacious plain near the city of Margus in the Upper Mæsia. The kings of the Huns assumed the solid benefits, as well as the vain honours, of the negotiation. They dictated the conditions of peace, and each condition was an insult on the majesty of the empire. Besides the freedom of a safe and plentiful market on the banks of the Danube, they required that the annual contribution should be augmented from three hundred and fifty to seven hundred Edition: current; Page: [4] pounds of gold; that a fine, or ransom, of eight pieces of gold should be paid for every Roman captive who had escaped from his Barbarian master; that the emperor should renounce all treaties and engagements with the enemies of the Huns; and that all the fugitives, who had taken refuge in the court or provinces of Theodosius, should be delivered to the justice of their offended sovereign. This justice was rigorously inflicted on some unfortunate youths of a royal race. They were crucified on the territories of the empire, by the command of Attila: and, as soon as the king of the Huns had impressed the Romans with the terror of his name, he indulged them in a short and arbitrary respite, whilst he subdued the rebellious or independent nations of Scythia and Germany.

Attila, the son of Mundzuk, deduced his noble, perhaps his regal, descent from the ancient Huns, who had formerly contended with the monarchs of China. His features, according to the observation of a Gothic historian, bore the stamp of his national origin; and the portrait of Attila exhibits the genuine deformity of a modern Calmuck: a large head, a swarthy complexion, small, deep-seated eyes, a flat nose, a few hairs in the place of a beard, broad shoulders, and a short square body, of nervous strength, though of a disproportioned form. The haughty step and demeanour of the king of the Huns expressed the consciousness of his superiority above the rest of mankind; and he had a custom of fiercely rolling his eyes, as if he wished to enjoy the terror Edition: current; Page: [5] which he inspired. Yet this savage hero was not inaccessible to pity: his suppliant enemies might confide in the assurance of peace or pardon; and Attila was considered by his subjects as a just and indulgent master. He delighted in war; but, after he had ascended the throne in a mature age, his head, rather than his hand, achieved the conquest of the North; and the fame of an adventurous soldier was usefully exchanged for that of a prudent and successful general. The effects of personal valour are so inconsiderable, except in poetry or romance, that victory, even among Barbarians, must depend on the degree of skill with which the passions of the multitude are combined and guided for the service of a single man. The Scythian conquerors, Attila and Zingis, surpassed their rude countrymen in art rather than in courage; and it may be observed that the monarchies, both of the Huns and of the Moguls, were erected by their founders on the basis of popular superstition. The miraculous conception, which fraud and credulity ascribed to the virgin-mother of Zingis, raised him above the level of human nature; and the naked prophet, who, in the name of the Deity, invested him with the empire of the earth, pointed the valour of the Moguls with irresistible enthusiasm. The religious arts of Attila were not less skilfully adapted to the character of his age and country. It was natural enough that the Scythians should adore, with peculiar devotion, the god of war; but, as they were incapable of forming either an abstract idea or a corporeal representation, they worshipped their tutelar deity under the symbol of an iron cimeter. One of the shepherds Edition: current; Page: [6] of the Huns perceived that a heifer, who was grazing, had wounded herself in the foot, and curiously followed the track of the blood, till he discovered, among the long grass, the point of an ancient sword, which he dug out of the ground and presented to Attila. That magnanimous, or rather that artful, prince accepted, with pious gratitude, this celestial favour; and, as the rightful possessor of the sword of Mars, asserted his divine and indefeasible claim to the dominion of the earth. If the rites of Scythia were practised on this solemn occasion, a lofty altar, or rather pile of faggots, three hundred yards in length and in breadth, was raised in a spacious plain; and the sword of Mars was placed erect on the summit of this rustic altar, which was annually consecrated by the blood of sheep, horses, and of the hundredth captive. Whether human sacrifices formed any part of the worship of Attila, or whether he propitiated the god of war with the victims which he continually offered in the field of battle, the favourite of Mars soon acquired a sacred character, which rendered his conquests more easy, and more permanent; and the Barbarian princes confessed, in the language of devotion and flattery, that they could not presume to gaze, with a steady eye, on the divine majesty of the king of the Huns. His brother Bleda, who reigned over a considerable part of the nation, was compelled to resign his sceptre and his Edition: current; Page: [7] life. Yet even this cruel act was attributed to a supernatural impulse; and the vigour with which Attila wielded the sword of Mars convinced the world that it had been reserved alone for his invincible arm. But the extent of his empire affords the only remaining evidence of the number and importance of his victories; and the Scythian monarch, however ignorant of the value of science and philosophy, might, perhaps, lament that his illiterate subjects were destitute of the art which could perpetuate the memory of his exploits.

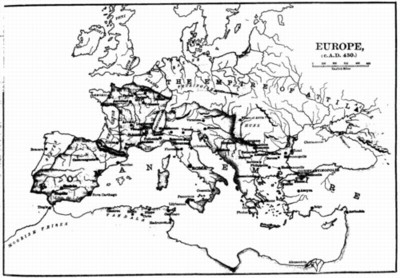

If a line of separation were drawn between the civilised and the savage climates of the globe; between the inhabitants of cities, who cultivated the earth, and the hunters and shepherds, who dwelt in tents; Attila might aspire to the title of supreme and sole monarch of the Barbarians. He alone, among the conquerors of ancient and modern times, united the two mighty kingdoms of Germany and Scythia; and those vague appellations, when they are applied to his reign, may be understood with an ample latitude. Thuringia, which stretched beyond its actual limits as far as the Danube, was in the number of his provinces; he interposed, with the weight of a powerful neighbour, in the domestic affairs of the Franks; and one of his lieutenants chastised, and almost exterminated, the Burgundians of the Rhine. He subdued the islands of the ocean, the kingdoms of Scandinavia, encompassed and divided by the waters of the Baltic; and the Huns might derive a tribute of furs from that Northern region which has been protected from all other conquerors by the severity of the climate and the courage of the natives. Towards the east, it is difficult to circumscribe the dominion of Edition: current; Page: [8] Attila over the Scythian deserts; yet we may be assured that he reigned on the banks of the Volga; that the king of the Huns was dreaded, not only as a warrior, but as a magician; that he insulted and vanquished the Khan of the formidable Geougen; and that he sent ambassadors to negotiate an equal alliance with the empire of China. In the proud review of the nations who acknowledged the sovereignty of Attila, and who never entertained, during his lifetime, the thought of a revolt, the Gepidæ and the Ostrogoths were distinguished by their numbers, their bravery, and the personal merit of their chiefs. The renowned Ardaric, king of the Gepidæ, was the faithful and sagacious counsellor of the monarch, who esteemed his intrepid genius, whilst he loved the mild and discreet virtues of the noble Walamir, king of the Ostrogoths. The crowd of vulgar kings, the leaders of so many martial tribes, who served under the standard of Attila, were ranged in the submissive order of guards and domestics, round the person of their master. They watched his nod; they trembled at his frown; and, at the first signal of his will, they executed, without murmur or hesitation, his stern and absolute commands. In time of peace, the dependent princes, with their national troops, attended the royal camp in regular succession; but, when Attila collected his military force, he was able to bring into the field an army of five, or according to another account of seven, hundred thousand Barbarians.

Edition: current; Page: [9]

The ambassadors of the Huns might awaken the attention of Theodosius, by reminding him that they were his neighbours both in Europe and Asia; since they touched the Danube on one hand, and reached, with the other, as far as the Tanais. In the reign of his father Arcadius, a band of adventurous Huns had ravaged the provinces of the East; from whence they brought away rich spoils and innumerable captives.

They advanced, by a secret path, along the shores of the Caspian Sea; traversed the snowy mountains of Armenia; passed the Tigris, the Euphrates, and the Halys; recruited their weary cavalry with the generous breed of Cappadocian horses; occupied the hilly country of Cilicia; and disturbed the festal songs and dances of the citizens of Antioch. Egypt trembled at their approach; and the monks and pilgrims of the Holy Land prepared to escape their fury by a speedy embarkation. The memory of this invasion was still recent in the minds of the Orientals. The subjects of Attila might execute, with superior forces, the design which these adventurers had so boldly attempted; and it soon became the subject of anxious conjecture, whether the tempest would fall on the dominions of Rome or of Persia. Some of the great vassals of the king of the Huns, who were themselves in the rank of powerful princes, had been sent to ratify an alliance Edition: current; Page: [10] and society of arms with the emperor, or rather with the general, of the West. They related, during their residence at Rome, the circumstances of an expedition which they had lately made into the East. After passing a desert and a morass, supposed by the Romans to be the lake Mæotis, they penetrated through the mountains, and arrived, at the end of fifteen days’ march, on the confines of Media; where they advanced as far as the unknown cities of Basic and Cursic. They encountered the Persian army in the plains of Media; and the air, according to their own expression, was darkened by a cloud of arrows. But the Huns were obliged to retire, before the numbers of the enemy. Their laborious retreat was effected by a different road; they lost the greatest part of their booty; and at length returned to the royal camp, with some knowledge of the country, and an impatient desire of revenge. In the free conversation of the Imperial ambassadors, who discussed, at the court of Attila, the character and designs of their formidable enemy, the ministers of Constantinople expressed their hope that his strength might be diverted and employed in a long and doubtful contest with the princes of the house of Sassan. The more sagacious Italians admonished their Eastern brethren of the folly and danger of such a hope, and convinced them that the Medes and Persians were incapable of resisting the arms of the Huns, and that the easy and important acquisition would exalt the pride, as well as power, of the conqueror. Instead of contenting himself with a moderate contribution, and a military title which equalled him only to the generals of Theodosius, Attila would proceed to impose a disgraceful and intolerable yoke on the necks of the prostrate and captive Romans, who would then be encompassed, on all sides, by the empire of the Huns.

Edition: current; Page: [11]

While the powers of Europe and Asia were solicitous to avert the impending danger, the alliance of Attila maintained the Vandals in the possession of Africa. An enterprise had been concerted between the courts of Ravenna and Constantinople, for the recovery of that valuable province; and the ports of Sicily were already filled with the military and naval forces of Theodosius. But the subtle Genseric, who spread his negotiations round the world, prevented their designs by exciting the king of the Huns to invade the Eastern empire; and a trifling incident soon became the motive, or pretence, of a destructive war. Under the faith of the treaty of Margus, a free market was held on the northern side of the Danube, which was protected by a Roman fortress surnamed Constantia. A troop of Barbarians violated the commercial security, killed, or dispersed, the unsuspecting traders, and levelled the fortress with the ground. The Huns justified this outrage as an act of reprisal; alleged that the bishop of Margus had entered their territories, to discover and steal a secret treasure of their kings; and sternly demanded the guilty prelate, the sacrilegious spoil, and the fugitive subjects, who had escaped from the justice of Attila. The refusal of the Byzantine court was the signal of war; and the Mæsians at first applauded the generous firmness of their sovereign. But they were soon intimidated by the destruction of Viminacium and the adjacent towns; and the people were persuaded to adopt the convenient maxim that a private citizen, however innocent Edition: current; Page: [12] or respectable, may be justly sacrificed to the safety of his country. The bishop of Margus, who did not possess the spirit of a martyr, resolved to prevent the designs which he suspected. He boldly treated with the princes of the Huns; secured, by solemn oaths, his pardon and reward; posted a numerous detachment of Barbarians, in silent ambush, on the banks of the Danube; and at the appointed hour opened, with his own hand, the gates of his episcopal city. This advantage, which had been obtained by treachery, served as a prelude to more honourable and decisive victories. The Illyrian frontier was covered by a line of castles and fortresses; and, though the greatest part of them consisted only of a single tower, with a small garrison, they were commonly sufficient to repel, or to intercept, the inroads of an enemy who was ignorant of the art, and impatient of the delay, of a regular siege. But these slight obstacles were instantly swept away by the inundation of the Huns. They destroyed, with fire and sword, the populous cities of Sirmium and Singidunum, of Ratiaria and Marcianopolis, of Naissus and Sardica; where every circumstance, in the discipline of the people and the construction of the buildings, had been gradually adapted to the sole purpose of defence. The whole breadth of Europe, as it extends above five hundred miles from the Euxine to the Hadriatic, was at once invaded, and occupied, and desolated by the myriads of Barbarians whom Attila led into the field. The public danger and distress could not, however, provoke Theodosius to interrupt his amusements and devotion, or to appear in person at the head of the Roman legions. But the troops which had been sent against Genseric were hastily recalled from Sicily; the garrisons on the side of Persia were exhausted; Edition: current; Page: [13] and a military force was collected in Europe, formidable by their arms and numbers, if the generals had understood the science of command, and their soldiers the duty of obedience. The armies of the Eastern empire were vanquished in three successive engagements; and the progress of Attila may be traced by the fields of battle. The two former, on the banks of the Utus, and under the walls of Marcianopolis, were fought in the extensive plains between the Danube and Mount Hæmus. As the Romans were pressed by a victorious enemy, they gradually, and unskilfully, retired towards the Chersonesus of Thrace; and that narrow peninsula, the last extremity of the land, was marked by their third, and irreparable, defeat. By the destruction of this army, Attila acquired the indisputable possession of the field. From the Hellespont to Thermopylæ and the suburbs of Constantinople, he ravaged, without resistance, and without mercy, the provinces of Thrace and Macedonia. Heraclea and Hadrianople might, perhaps, escape this dreadful irruption of the Huns; but the words the most expressive of total extirpation and erasure are applied to the calamities which they inflicted on seventy cities of the Eastern empire. Theodosius, his court, and the unwarlike people were protected by the walls of Constantinople; but those walls had been shaken by a recent earthquake, and the fall of fifty-eight towers had opened a large and tremendous breach. The damage indeed was speedily repaired; but this accident was aggravated by a superstitious fear that Heaven itself had delivered the Imperial city to the shepherds of Scythia, who were strangers to the laws, the language, and the religion of the Romans.

Edition: current; Page: [14]

In all their invasions of the civilised empires of the South, the Scythian shepherds have been uniformly actuated by a savage and destructive spirit. The laws of war, that restrain the exercise of national rapine and murder, are founded on two principles of substantial interest: the knowledge of the permanent benefits which may be obtained by a moderate use of conquest; and a just apprehension lest the desolation which we inflict on the enemy’s country may be retaliated on our own. But these considerations of hope and fear are almost unknown in the pastoral state of nations. The Huns of Attila may, without injustice, be compared to the Moguls and Tartars, before their primitive manners were changed by religion and luxury; and the evidence of Oriental history may reflect some light on the short and imperfect annals of Rome. After the Moguls had subdued the northern provinces of China, it was seriously proposed, not in the hour of victory and passion, but in calm deliberate council, to exterminate all the inhabitants of that populous country, that the vacant land might be converted to the pasture of cattle. The firmness of a Chinese mandarin, who insinuated some principles of rational policy into the mind of Zingis, diverted him from the execution of this horrid design. But in the cities of Asia, which yielded to the Moguls, the inhuman abuse of the rights of war was exercised, with a regular form of discipline, which may, with equal reason, though not with equal authority, be imputed to the victorious Huns. The inhabitants, who had submitted to their discretion, were ordered to evacuate their houses, and to assemble in some plain adjacent Edition: current; Page: [15] to the city; where a division was made of the vanquished into three parts. The first class consisted of the soldiers of the garrison, and of the young men capable of bearing arms; and their fate was instantly decided: they were either enlisted among the Moguls, or they were massacred on the spot by the troops, who, with pointed spears and bended bows, had formed a circle round the captive multitude. The second class, composed of the young and beautiful women, of the artificers of every rank and profession, and of the more wealthy or honourable citizens, from whom a private ransom might be expected, was distributed in equal or proportionable lots. The remainder, whose life or death was alike useless to the conquerors, were permitted to return to the city; which, in the meanwhile, had been stripped of its valuable furniture; and a tax was imposed on those wretched inhabitants for the indulgence of breathing their native air. Such was the behaviour of the Moguls, when they were not conscious of any extraordinary rigour. But the most casual provocation, the slightest motive of caprice or convenience, often provoked them to involve a whole people in an indiscriminate massacre; and the ruin of some flourishing cities was executed with such unrelenting perseverance that, according to their own expression, horses might run, without stumbling, over the ground where they had once stood. The three great capitals of Khorasan, Maru, Neisabour, and Herat were destroyed by the armies of Zingis; and the exact account which was taken of the slain amounted to four millions three hundred and forty-seven thousand persons. Timur, or Tamerlane, was educated in Edition: current; Page: [16] a less barbarous age, and in the profession of the Mahometan religion; yet, if Attila equalled the hostile ravages of Tamerlane, either the Tartar or the Hun might deserve the epithet of the Scourge of God.

It may be affirmed, with bolder assurance, that the Huns depopulated the provinces of the empire, by the number of Roman subjects whom they led away into captivity. In the hands of a wise legislator, such an industrious colony might have contributed to diffuse, through the deserts of Scythia, the rudiments of the useful and ornamental arts; but these captives, who had been taken in war, were accidentally dispersed among the hordes that obeyed the empire of Attila. The estimate of their respective value was formed by the simple judgment of unenlightened and unprejudiced Barbarians. Perhaps they might not understand the merit of a theologian, profoundly skilled in the controversies of the Trinity and the Incarnation; yet they respected the ministers of every religion; and the active zeal of the Christian missionaries, without approaching the person or the palace of the monarch, successfully laboured in the propagation of the gospel. The pastoral tribes, who were ignorant of the Edition: current; Page: [17] distinction of landed property, must have disregarded the use, as well as the abuse, of civil jurisprudence; and the skill of an eloquent lawyer could excite only their contempt, or their abhorrence. The perpetual intercourse of the Huns and the Goths had communicated the familiar knowledge of the two national dialects; and the Barbarians were ambitious of conversing in Latin, the military idiom even of the Eastern empire. But they disdained the language, and the sciences, of the Greeks; and the vain sophist, or grave philosopher, who had enjoyed the flattering applause of the schools, was mortified to find that his robust servant was a captive of more value and importance than himself. The mechanic arts were encouraged and esteemed, as they tended to satisfy the wants of the Huns. An architect, in the service of Onegesius, one of the favourites of Attila, was employed to construct a bath; but this work was a rare example of private luxury; and the trades of the smith, the carpenter, the armourer, were much more adapted to supply a wandering people with the useful instruments of peace and war. But the merit of the physician was received with universal favour and respect; the Barbarians, who despised death, might be apprehensive of disease; and the haughty conqueror trembled in the presence of a captive, to whom he ascribed, perhaps, an imaginary power of prolonging, or preserving, his life. The Huns might be provoked to insult the misery of their slaves, over whom they exercised a despotic command; Edition: current; Page: [18] but their manners were not susceptible of a refined system of oppression; and the efforts of courage and diligence were often recompensed by the gift of freedom. The historian Priscus, whose embassy is a course of curious instruction, was accosted, in the camp of Attila, by a stranger, who saluted him in the Greek language, but whose dress and figure displayed the appearance of a wealthy Scythian. In the siege of Viminacium, he had lost, according to his own account, his fortune and liberty; he became the slave of Onegesius; but his faithful services, against the Romans and the Acatzires, had gradually raised him to the rank of the native Huns; to whom he was attached by the domestic pledges of a new wife and several children. The spoils of war had restored and improved his private property; he was admitted to the table of his former lord; and the apostate Greek blessed the hour of his captivity, since it had been the introduction to an happy and independent state; which he held by the honourable tenure of military service. This reflection naturally produced a dispute on the advantages, and defects, of the Roman government, which was severely arraigned by the apostate, and defended by Priscus in a prolix and feeble declamation. The freedman of Onegesius exposed, in true and lively colours, the vices of a declining empire, of which he had so long been the victim; the cruel absurdity of the Roman princes, unable to protect their subjects against the public enemy, unwilling to trust them with arms for their own defence; the intolerable weight of taxes, rendered still more oppressive by the intricate or arbitrary modes of collection; the obscurity of numerous and contradictory laws; the tedious and expensive forms of judicial proceedings; the Edition: current; Page: [19] partial administration of justice; and the universal corruption, which increased the influence of the rich, and aggravated the misfortunes of the poor. A sentiment of patriotic sympathy was at length revived in the breast of the fortunate exile; and he lamented, with a flood of tears, the guilt or weakness of those magistrates who had perverted the wisest and most salutary institutions.

The timid, or selfish, policy of the Western Romans had abandoned the Eastern empire to the Huns. The loss of armies, and the want of discipline or virtue, were not supplied by the personal character of the monarch. Theodosius might still affect the style, as well as the title, of Invincible Augustus; but he was reduced to solicit the clemency of Attila, who imperiously dictated these harsh and humiliating conditions of peace. I. The emperor of the East resigned, by an express or tacit convention, an extensive and important territory, which stretched along the southern banks of the Danube, from Singidunum, or Belgrade, as far as Novæ, in the diocese of Thrace. The breadth was defined by the vague computation of fifteen days’ journey; but, from the proposal of Attila to remove the situation of the national market, it soon appeared that he comprehended the ruined city of Naissus within the limits of his dominions. II. The king of the Huns required and obtained, that his tribute or subsidy should be augmented from seven hundred pounds of gold to the annual sum of two thousand one hundred; and he stipulated the immediate payment of six thousand pounds of gold to defray the expenses, or to expiate the guilt, of the war. One might imagine that such a demand, which scarcely equalled the measure of private wealth, would have been readily discharged by the opulent empire of the Edition: current; Page: [20] East; and the public distress affords a remarkable proof of the impoverished, or at least of the disorderly, state of the finances. A large proportion of the taxes, extorted from the people, was detained and intercepted in their passage, through the foulest channels, to the treasury of Constantinople. The revenue was dissipated by Theodosius and his favourites in wasteful and profuse luxury; which was disguised by the names of Imperial magnificence or Christian charity. The immediate supplies had been exhausted by the unforeseen necessity of military preparations. A personal contribution, rigorously, but capriciously, imposed on the members of the senatorian order, was the only expedient that could disarm, without loss of time, the impatient avarice of Attila; but the poverty of the nobles compelled them to adopt the scandalous resource of exposing to public auction the jewels of their wives and the hereditary ornaments of their palaces. III. The king of the Huns appears to have established, as a principle of national jurisprudence, that he could never lose the property which he had once acquired in the persons who had yielded either a voluntary or reluctant submission to his authority. From this principle he concluded, and the conclusions of Attila were irrevocable laws, that the Huns who had been taken prisoners in war should be released without delay and without ransom; that every Roman captive who had presumed to escape should purchase his right to freedom at the price of twelve pieces of gold; and that all the Barbarians who had deserted the standard of Attila should be restored, without any promise, or stipulation, of pardon. In the execution of this cruel and ignominious treaty, the Imperial officers were forced to massacre several loyal and noble deserters, who refused to devote Edition: current; Page: [21] themselves to certain death; and the Romans forfeited all reasonable claims to the friendship of any Scythian people, by this public confession that they were destitute either of faith or power to protect the suppliants who had embraced the throne of Theodosius.

The firmness of a single town, so obscure that, except on this occasion, it has never been mentioned by any historian or geographer, exposed the disgrace of the emperor and empire. Azimus, or Azimuntium, a small city of Thrace on the Illyrian borders, had been distinguished by the martial spirit of its youth, the skill and reputation of the leaders whom they had chosen, and their daring exploits against the innumerable host of the Barbarians. Instead of tamely expecting their approach, the Azimuntines attacked, in frequent and successful sallies, the troops of the Huns, who gradually declined the dangerous neighbourhood; rescued from their hands the spoil and the captives; and recruited their domestic force by the voluntary association of fugitives and deserters. After the conclusion of the treaty, Attila still menaced the empire with implacable war, unless the Azimuntines were persuaded, or compelled, to comply with the conditions which their sovereign had accepted. The ministers of Theodosius confessed with shame, and with Edition: current; Page: [22] truth, that they no longer possessed any authority over a society of men, who so bravely asserted their natural independence; and the king of the Huns condescended to negotiate an equal exchange with the citizens of Azimus. They demanded the restitution of some shepherds, who, with their cattle, had been accidentally surprised. A strict, though fruitless, inquiry was allowed; but the Huns were obliged to swear that they did not detain any prisoners belonging to the city, before they could recover two surviving countrymen, whom the Azimuntines had reserved as pledges for the safety of their lost companions. Attila, on his side, was satisfied, and deceived, by their solemn asseveration that the rest of the captives had been put to the sword; and that it was their constant practice immediately to dismiss the Romans and the deserters, who had obtained the security of the public faith. This prudent and officious dissimulation may be condemned or excused by the casuists, as they incline to the rigid decree of St. Augustin or to the milder sentiment of St. Jerom and St. Chrysostom; but every soldier, every statesman, must acknowledge that, if the race of the Azimuntines had been encouraged and multiplied, the Barbarians would have ceased to trample on the majesty of the empire.

It would have been strange, indeed, if Theodosius had purchased, by the loss of honour, a secure and solid tranquillity; or if his tameness had not invited the repetition of injuries. The Byzantine court was insulted by five or six successive embassies; and the ministers of Attila were uniformly instructed to press the tardy or imperfect execution of the Edition: current; Page: [23] last treaty; to produce the names of fugitives and deserters, who were still protected by the empire; and to declare, with seeming moderation, that, unless their sovereign obtained complete and immediate satisfaction, it would be impossible for him, were it even his wish, to check the resentment of his warlike tribes. Besides the motives of pride and interest which might prompt the king of the Huns to continue this train of negotiation, he was influenced by the less honourable view of enriching his favourites at the expense of his enemies. The Imperial treasury was exhausted, to procure the friendly offices of the ambassadors and their principal attendants, whose favourable report might conduce to the maintenance of peace. The Barbarian monarch was flattered by the liberal reception of his ministers; he computed with pleasure the value and splendour of their gifts, rigorously exacted the performance of every promise which would contribute to their private emolument, and treated as an important business of state the marriage of his secretary Constantius. That Gallic adventurer, who was recommended by Aetius to the king of the Huns, had engaged his service to the ministers of Constantinople, for the stipulated reward of a wealthy and noble wife; and the daughter of Count Saturninus was chosen to discharge the obligations of her country. The reluctance of the victim, some domestic troubles, and the unjust confiscation of her fortune cooled the ardour of her interested lover; but he still demanded, in the name of Attila, an equivalent alliance; and, after many ambiguous delays and excuses, the Byzantine court was compelled to sacrifice to this insolent stranger the widow Edition: current; Page: [24] of Armatius, whose birth, opulence, and beauty placed her in the most illustrious rank of the Roman matrons. For these importunate and oppressive embassies, Attila claimed a suitable return; he weighed, with suspicious pride, the character and station of the Imperial envoys; but he condescended to promise that he would advance as far as Sardica, to receive any ministers who had been invested with the consular dignity. The council of Theodosius eluded this proposal by representing the desolate and ruined condition of Sardica; and even ventured to insinuate that every officer of the army or household was qualified to treat with the most powerful princes of Scythia. Maximin, a respectable courtier, whose abilities had been long exercised in civil and military employments, accepted with reluctance the troublesome and, perhaps, dangerous commission of reconciling the angry spirit of the king of the Huns. His friend, the historian Priscus, embraced the opportunity of observing the Barbarian hero in the peaceful and domestic scenes of life; but the secret of the embassy, a fatal and guilty secret, was entrusted only to the interpreter Vigilius. The two last ambassadors of the Huns, Orestes, a noble subject of the Pannonian province, and Edecon, a valiant chieftain of the tribe of the Scyri, returned at the same time from Constantinople to the royal camp. Their obscure names were afterwards illustrated by the extraordinary fortune and the contrast Edition: current; Page: [25] of their sons; the two servants of Attila became the fathers of the last Roman emperor of the West and of the first Barbarian king of Italy.

The ambassadors, who were followed by a numerous train of men and horses, made their first halt at Sardica, at the distance of three hundred and fifty miles, or thirteen days’ journey, from Constantinople. As the remains of Sardica were still included within the limits of the empire, it was incumbent on the Romans to exercise the duties of hospitality. They provided, with the assistance of the provincials, a sufficient number of sheep and oxen; and invited the Huns to a splendid, or at least a plentiful, supper. But the harmony of the entertainment was soon disturbed by mutual prejudice and indiscretion. The greatness of the emperor and the empire was warmly maintained by their ministers; the Huns, with equal ardour, asserted the superiority of their victorious monarch: the dispute was inflamed by the rash and unseasonable flattery of Vigilius, who passionately rejected the comparison of a mere mortal with the divine Theodosius; and it was with extreme difficulty that Maximin and Priscus were able to divert the conversation, or to soothe the angry minds of the Barbarians. When they rose from table, the Imperial ambassador presented Edecon and Orestes with rich gifts of silk robes and Indian pearls, which they thankfully accepted. Yet Orestes could not forbear insinuating that he had not always been treated with such respect and liberality; the offensive distinction which was implied between his civil office and the hereditary rank of his colleague seems to have made Edecon a doubtful friend, and Orestes an irreconcileable enemy. After this entertainment, they travelled about one hundred miles from Sardica to Naissus. That flourishing city, which had given birth to the great Constantine, was levelled with the ground; the inhabitants were destroyed or dispersed; and the appearance of some sick persons, who were still permitted to exist among the ruins of the churches, served only to increase Edition: current; Page: [26] the horror of the prospect. The surface of the country was covered with the bones of the slain; and the ambassadors, who directed their course to the north-west, were obliged to pass the hills of modern Servia, before they descended into the flat and marshy grounds which are terminated by the Danube. The Huns were masters of the great river; their navigation was performed in large canoes, hollowed out of the trunk of a single tree; the ministers of Theodosius were safely landed on the opposite bank; and their Barbarian associates immediately hastened to the camp of Attila, which was equally prepared for the amusements of hunting or of war. No sooner had Maximin advanced about two miles from the Danube, than he began to experience the fastidious insolence of the conqueror. He was sternly forbid to pitch his tents in a pleasant valley, lest he should infringe the distant awe that was due to the royal mansion. The ministers of Attila pressed him to communicate the business and the instructions, which he reserved for the ear of their sovereign. When Maximin temperately urged the contrary practice of nations, he was still more confounded to find that the resolutions of the Sacred Consistory, those secrets (says Priscus) which should not be revealed to the gods themselves, had been treacherously disclosed to the public enemy. On his refusal to comply with such ignominious terms, the Imperial envoy was commanded instantly to depart; the order was recalled; it was again repeated; and the Huns renewed their ineffectual attempts to subdue the patient firmness of Maximin. At length, by the intercession of Scotta, the brother of Onegesius, whose friendship had been purchased by a liberal gift, he was admitted to the royal presence: but, instead of obtaining a decisive answer, he was compelled to undertake a remote journey towards the North, that Attila might enjoy the proud satisfaction of receiving, in the same camp, the ambassadors of the Eastern and Western empires. His journey was regulated by the guides, who obliged him to halt, to hasten his march, or to deviate from the common Edition: current; Page: [27] road, as it best suited the convenience of the king. The Romans who traversed the plains of Hungary suppose that they passed several navigable rivers, either in canoes or portable boats; but there is reason to suspect that the winding stream of the Theiss, or Tibiscus, might present itself in different places, under different names. From the contiguous villages they received a plentiful and regular supply of provisions; mead instead of wine, millet in the place of bread, and a certain liquor named camus, which, according to the report of Priscus, was distilled from barley. Such fare might appear coarse and indelicate to men who had tasted the luxury of Constantinople: but, in their accidental distress, they were relieved by the gentleness and hospitality of the same Barbarians, so terrible and so merciless in war. The ambassadors had encamped on the edge of a large morass. A violent tempest of wind and rain, of thunder and lightning, overturned their tents, immersed their baggage and furniture in the water, and scattered their retinue, who wandered in the darkness of the night, uncertain of their road, and apprehensive of some unknown danger, till they awakened by their cries the inhabitants of a neighbouring village, the property of the widow of Bleda. A bright illumination, and, in a few moments, a comfortable fire of reeds, was kindled by their officious benevolence; the wants, and even the desires, of the Romans were liberally satisfied; and they seem to have been embarrassed by the singular politeness of Bleda’s widow, who added to her other favours the gift, or at least the loan, of a sufficient number of beautiful and obsequious damsels. The sunshine of the succeeding day was dedicated Edition: current; Page: [28] to repose; to collect and dry the baggage, and to the refreshment of the men and horses: but, in the evening, before they pursued their journey, the ambassadors expressed their gratitude to the bounteous lady of the village, by a very acceptable present of silver cups, red fleeces, dried fruits, and Indian pepper. Soon after this adventure, they rejoined the march of Attila, from whom they had been separated about six days; and slowly proceeded to the capital of an empire which did not contain, in the space of several thousand miles, a single city.

As far as we may ascertain the vague and obscure geography of Priscus, this capital appears to have been seated between the Danube, the Theiss, and the Carpathian hills, in the plains of Upper Hungary, and most probably in the neighbourhood of Jazberin, Agria, or Tokay. In its origin it could be no more than an accidental camp, which, by the long and frequent residence of Attila, had insensibly swelled into a huge village, for the reception of his court, of the troops who followed his person, and of the various multitude of idle or industrious slaves and retainers. The baths, constructed by Onegesius, were the only edifice of stone; the materials had been transported from Pannonia; and, since the adjacent country was destitute even of large timber, it may be presumed that the meaner habitations of the royal Edition: current; Page: [29] village consisted of straw, of mud, or of canvas. The wooden houses of the more illustrious Huns were built and adorned with rude magnificence, according to the rank, the fortune, or the taste of the proprietors. They seem to have been distributed with some degree of order and symmetry; and each spot became more honourable, as it approached the person of the sovereign. The palace of Attila, which surpassed all other houses in his dominions, was built entirely of wood, and covered an ample space of ground. The outward enclosure was a lofty wall, or palisade of smooth square timber, intersected with high towers, but intended rather for ornament than defence. This wall, which seems to have encircled the declivity of a hill, comprehended a great variety of wooden edifices, adapted to the uses of royalty. A separate house was assigned to each of the numerous wives of Attila; and, instead of the rigid and illiberal confinement imposed by Asiatic jealousy, they politely admitted the Roman ambassadors to their presence, their table, and even to the freedom of an innocent embrace. When Maximin offered his presents to Cerca, the principal queen, he admired the singular architecture of her mansion, the height of the round columns, the size and beauty of the wood, which was curiously shaped, or turned, or polished, or carved; and his attentive eye was able to discover some taste in the ornaments, and some regularity in the proportions. After passing through the guards who watched before the gate, the ambassadors were introduced into the private apartment of Cerca. The wife of Attila received their visit sitting, or rather lying, on a soft couch; the floor was covered with a carpet; the domestics formed a circle round the queen; and her damsels, seated on the ground, were employed in working the variegated embroidery which adorned the dress of the Barbaric warriors. The Huns were ambitious of displaying those riches which were the fruit and evidence of their victories: the trappings of their horses, their swords, and even their shoes were studded with gold and precious stones; Edition: current; Page: [30] and their tables were profusely spread with plates, and goblets, and vases of gold and silver, which had been fashioned by the labour of Grecian artists. The monarch alone assumed the superior pride of still adhering to the simplicity of his Scythian ancestors. The dress of Attila, his arms, and the furniture of his horse were plain, without ornament, and of a single colour. The royal table was served in wooden cups and platters; flesh was his only food; and the conqueror of the North never tasted the luxury of bread.

When Attila first gave audience to the Roman ambassadors on the banks of the Danube, his tent was encompassed with a formidable guard. The monarch himself was seated in a wooden chair. His stern countenance, angry gestures, and impatient tone astonished the firmness of Maximin; but Vigilius had more reason to tremble, since he distinctly understood the menace that, if Attila did not respect the law of nations, he would nail the deceitful interpreter to a cross and leave his body to the vultures. The Barbarian condescended, by producing an accurate list, to expose the bold falsehood of Vigilius, who had affirmed that no more than seventeen deserters could be found. But he arrogantly declared that he apprehended only the disgrace of contending with his fugitive slaves; since he despised their impotent efforts to defend the provinces which Theodosius had entrusted to their arms: “For what fortress” (added Attila), “what city, in the wide extent of the Roman empire, can hope to exist, secure and impregnable, if it is our pleasure that it should be erased from the earth?” He dismissed, however, the interpreter, who returned to Constantinople with his peremptory demand of more complete restitution and a more splendid embassy. His anger gradually subsided, Edition: current; Page: [31] and his domestic satisfaction in a marriage which he celebrated on the road with the daughter of Eslam might perhaps contribute to mollify the native fierceness of his temper. The entrance of Attila into the royal village was marked by a very singular ceremony. A numerous troop of women came out to meet their hero, and their king. They marched before him, distributed into long and regular files; the intervals between the files were filled by white veils of thin linen, which the women on either side bore aloft in their hands, and which formed a canopy for a chorus of young virgins, who chanted hymns and songs in the Scythian language. The wife of his favourite Onegesius, with a train of female attendants, saluted Attila at the door of her own house, on his way to the palace; and offered, according to the custom of the country, her respectful homage, by entreating him to taste the wine and meat which she had prepared for his reception. As soon as the monarch had graciously accepted her hospitable gift, his domestics lifted a small silver table to a convenient height, as he sat on horseback; and Attila, when he had touched the goblet with his lips, again saluted the wife of Onegesius, and continued his march. During his residence at the seat of empire, his hours were not wasted in the recluse idleness of a seraglio; and the king of the Huns could maintain his superior dignity, without concealing his person from the public view. He frequently assembled his council, and gave audience to the ambassadors of the nations; and his people might appeal to the supreme tribunal, which he held at stated times, and, according to the Eastern custom, before the principal gate of his wooden palace. The Romans, both of the East and of the West, were twice invited to the banquets, where Attila feasted with the princes and nobles of Scythia. Maximin and his Edition: current; Page: [32] colleagues were stopped on the threshold, till they had made a devout libation to the health and prosperity of the king of the Huns; and were conducted, after this ceremony, to their respective seats in a spacious hall. The royal table and couch, covered with carpets and fine linen, was raised by several steps in the midst of the hall; and a son, an uncle, or perhaps a favourite king, were admitted to share the simple and homely repast of Attila. Two lines of small tables, each of which contained three or four guests, were ranged in order on either hand; the right was esteemed the most honourable, but the Romans ingenuously confess that they were placed on the left; and that Beric, an unknown chieftain, most probably of the Gothic race, preceded the representatives of Theodosius and Valentinian. The Barbarian monarch received from his cup-bearer a goblet filled with wine, and courteously drank to the health of the most distinguished guest, who rose from his seat and expressed, in the same manner, his loyal and respectful vows. This ceremony was successively performed for all, or at least for the illustrious persons of the assembly; and a considerable time must have been consumed, since it was thrice repeated, as each course or service was placed on the table. But the wine still remained after the meat had been removed; and the Huns continued to indulge their intemperance long after the sober and decent ambassadors of the two empires had withdrawn themselves from the nocturnal banquet. Yet before they retired, they enjoyed a singular opportunity of observing the manners of the nation in their convivial amusements. Two Scythians stood before the couch of Attila, and recited the verses which they had composed, to celebrate his valour and his victories. A profound silence prevailed in the hall; and the attention of the guests was captivated by the vocal harmony, which revived and perpetuated the memory of their own exploits: a martial ardour flashed from the eyes of the warriors, who were impatient for battle; and the tears of the old men expressed their generous despair that they could no Edition: current; Page: [33] longer partake the danger and glory of the field. This entertainment, which might be considered as a school of military virtue, was succeeded by a farce that debased the dignity of human nature. A Moorish and a Scythian buffoon successively excited the mirth of the rude spectators, by their deformed figure, ridiculous dress, antic gestures, absurd speeches, and the strange unintelligible confusion of the Latin, the Gothic, and the Hunnic languages; and the hall resounded with loud and licentious peals of laughter. In the midst of this intemperate riot, Attila alone, without a change of countenance, maintained his stedfast and inflexible gravity; which was never relaxed, except on the entrance of Irnac, the youngest of his sons: he embraced the boy with a smile of paternal tenderness, gently pinched him by the cheek, and betrayed a partial affection, which was justified by the assurance of his prophets that Irnac would be the future support of his family and empire. Two days afterwards, the ambassadors received a second invitation; and they had reason to praise the politeness as well as the hospitality of Attila. The king of the Huns held a long and familiar conversation with Maximin; but his civility was interrupted by rude expressions, and haughty reproaches; and he was provoked, by a motive of interest, to support, with unbecoming zeal, the private claims of his secretary Constantius. “The emperor” (said Attila) “has long promised him a rich wife; Constantius must not be disappointed; nor should a Roman emperor deserve the name of liar.” On the third day, the ambassadors were dismissed; the freedom of several captives was granted, for a moderate ransom, to their pressing entreaties; and, besides the royal presents, they were permitted to accept from each of the Scythian nobles the honourable and useful gift of a horse. Edition: current; Page: [34] Maximin returned, by the same road, to Constantinople; and though he was involved in an accidental dispute with Beric, the new ambassador of Attila, he flattered himself that he had contributed, by the laborious journey, to confirm the peace and alliance of the two nations.

But the Roman ambassador was ignorant of the treacherous design, which had been concealed under the mask of the public faith. The surprise and satisfaction of Edecon, when he contemplated the splendour of Constantinople, had encouraged the interpreter Vigilius to procure for him a secret interview with the eunuch Chrysaphius, who governed the emperor and the empire. After some previous conversation, and a mutual oath of secrecy, the eunuch, who had not, from his own feelings or experience, imbibed any exalted notions of ministerial virtue, ventured to propose the death of Attila, as an important service, by which Edecon might deserve a liberal share of the wealth and luxury which he admired. The ambassador of the Huns listened to the tempting offer, and professed, with apparent zeal, his ability, as well as readiness, to execute the bloody deed; the design was communicated to the master of the offices, and the devout Theodosius consented to the assassination of his invincible enemy. But this perfidious conspiracy was defeated by the dissimulation, or the repentance, of Edecon; and, though he might exaggerate his inward abhorrence for the treason, which he Edition: current; Page: [35] seemed to approve, he dexterously assumed the merit of an early and voluntary confession. If we now review the embassy of Maximin, and the behaviour of Attila, we must applaud the Barbarian, who respected the laws of hospitality, and generously entertained and dismissed the minister of a prince who had conspired against his life. But the rashness of Vigilius will appear still more extraordinary, since he returned, conscious of his guilt and danger, to the royal camp; accompanied by his son, and carrying with him a weighty purse of gold, which the favourite eunuch had furnished, to satisfy the demands of Edecon, and to corrupt the fidelity of the guards. The interpreter was instantly seized, and dragged before the tribunal of Attila, where he asserted his innocence with specious firmness, till the threat of inflicting instant death on his son extorted from him a sincere discovery of the criminal transaction. Under the name of ransom or confiscation, the rapacious king of the Huns accepted two hundred pounds of gold for the life of a traitor, whom he disdained to punish. He pointed his just indignation against a nobler object. His ambassadors Eslaw and Orestes were immediately despatched to Constantinople with a peremptory instruction, which it was much safer for them to execute than to disobey. They boldly entered the Imperial presence, with the fatal purse hanging down from the neck of Orestes; who interrogated the eunuch Chrysaphius, as he stood beside the throne, whether he recognised the evidence of his guilt. But the office of reproof was reserved for the superior dignity of his colleague Eslaw, who gravely addressed the Emperor of the East in the following words: “Theodosius is the son of an illustrious and respectable parent; Attila likewise is descended from a noble race; and he has supported, by his actions, the dignity which he inherited from his father Mundzuk. But Theodosius has forfeited his paternal honours, and, by consenting to pay tribute, has degraded himself to the condition of a slave. It is therefore just that he should reverence the man whom fortune and merit have placed above Edition: current; Page: [36] him; instead of attempting, like a wicked slave, clandestinely to conspire against his master.” The son of Arcadius, who was accustomed only to the voice of flattery, heard with astonishment the severe language of truth; he blushed and trembled; nor did he presume directly to refuse the head of Chrysaphius, which Eslaw and Orestes were instructed to demand. A solemn embassy, armed with full powers and magnificent gifts, was hastily sent to deprecate the wrath of Attila; and his pride was gratified by the choice of Nomius and Anatolius, two ministers of consular or patrician rank, of whom the one was great treasurer, and the other was master-general of the armies of the East. He condescended to meet these ambassadors on the banks of the river Drenco; and, though he at first affected a stern and haughty demeanour, his anger was insensibly mollified by their eloquence and liberality. He condescended to pardon the emperor, the eunuch, and the interpreter; bound himself by an oath to observe the conditions of peace; to release a great number of captives; abandoned the fugitives and deserters to their fate; and resigned a large territory to the south of the Danube, which he had already exhausted of its wealth and its inhabitants. But this treaty was purchased at an expense which might have supported a vigorous and successful war; and the subjects of Theodosius were compelled to redeem the safety of a worthless favourite by oppressive taxes, which they would more cheerfully have paid for his destruction.

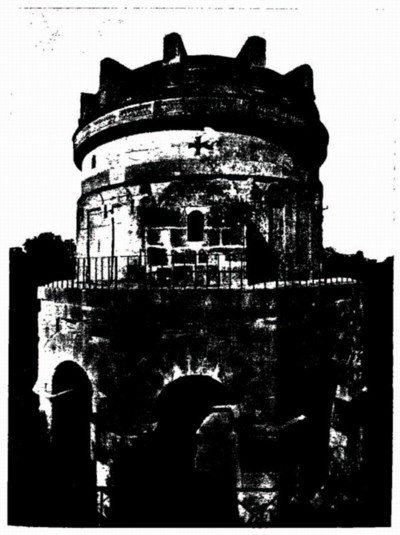

The emperor Theodosius did not long survive the most humiliating circumstance of an inglorious life. As he was riding, or hunting, in the neighbourhood of Constantinople, he was thrown from his horse into the river Lycus; the spine of Edition: current; Page: [37] the back was injured by the fall; and he expired some days afterwards, in the fiftieth year of his age, and the forty-third of his reign. His sister Pulcheria, whose authority had been controlled both in civil and ecclesiastical affairs by the pernicious influence of the eunuchs, was unanimously proclaimed empress of the East; and the Romans, for the first time, submitted to a female reign. No sooner had Pulcheria ascended the throne than she indulged her own and the public resentment by an act of popular justice. Without any legal trial, the eunuch Chrysaphius was executed before the gates of the city; and the immense riches which had been accumulated by the rapacious favourite served only to hasten and to justify his punishment. Amidst the general acclamations of the clergy and people, the empress did not forget the prejudice and disadvantage to which her sex was exposed; and she wisely resolved to prevent their murmurs by the choice of a colleague, who would always respect the superior rank and virgin chastity of his wife. She gave her hand to Marcian, a senator, about sixty years of age, and the nominal husband of Pulcheria was solemnly invested with the Imperial purple. The zeal which he displayed for the orthodox creed, as it was established by the council of Chalcedon, would alone have inspired the grateful eloquence of the Catholics. But the behaviour of Marcian in a private life, and afterwards on the throne, may support a more rational belief that he was qualified to restore and invigorate an empire which had been almost dissolved by the successive weakness of two hereditary monarchs. He was born in Thrace, and educated to the profession of arms; but Marcian’s Edition: current; Page: [38] youth had been severely exercised by poverty and misfortune, since his only resource, when he first arrived at Constantinople, consisted in two hundred pieces of gold, which he had borrowed of a friend. He passed nineteen years in the domestic and military service of Aspar and his son Ardaburius; followed those powerful generals to the Persian and African wars; and obtained, by their influence, the honourable rank of tribune and senator. His mild disposition, and useful talents, without alarming the jealousy, recommended Marcian to the esteem and favour, of his patrons; he had seen, perhaps he had felt, the abuses of a venal and oppressive administration; and his own example gave weight and energy to the laws which he promulgated for the reformation of manners.

Edition: current; Page: [39]

CHAPTER XXXV

Invasion of Gaul by Attila — He is repulsed by Aetius and the Visigoths — Attila invades and evacuates Italy — The deaths of Attila, Aetius, and Valentinian the Third

It was the opinion of Marcian that war should be avoided, as long as it is possible to preserve a secure and honourable peace; but it was likewise his opinion that peace cannot be honourable or secure, if the sovereign betrays a pusillanimous aversion to war. This temperate courage dictated his reply to the demands of Attila, who insolently pressed the payment of the annual tribute. The emperor signified to the Barbarians that they must no longer insult the majesty of Rome, by the mention of a tribute; that he was disposed to reward with becoming liberality the faithful friendship of his allies; but that if they presumed to violate the public peace, they should feel that he possessed troops, and arms, and resolution, to repel their attacks. The same language, even in the camp of the Huns, was used by his ambassador Apollonius, whose bold refusal to deliver the presents, till he had been admitted to a personal interview, displayed a sense of dignity, and a contempt of danger, which Attila was not prepared to expect from the degenerate Romans. He threatened to chastise the rash successor of Theodosius; but he hesitated whether he should first direct his invincible arms against the Eastern or the Western empire. While mankind awaited his decision with awful suspense, he sent an equal defiance to the courts of Ravenna and Constantinople, and his ministers saluted the two emperors with the same haughty declaration. “Attila, my Lord, and thy lord, commands thee to provide a palace for Edition: current; Page: [40] his immediate reception.” But, as the Barbarian despised, or affected to despise, the Romans of the East, whom he had so often vanquished, he soon declared his resolution of suspending the easy conquest, till he had achieved a more glorious and important enterprise. In the memorable invasions of Gaul and Italy, the Huns were naturally attracted by the wealth and fertility of those provinces; but the particular motives and provocations of Attila can only be explained by the state of the Western empire under the reign of Valentinian, or, to speak more correctly, under the administration of Aetius.

After the death of his rival Boniface, Aetius had prudently retired to the tents of the Huns; and he was indebted to their alliance for his safety and his restoration. Instead of the suppliant language of a guilty exile, he solicited his pardon at the head of sixty thousand Barbarians; and the empress Placidia confessed, by a feeble resistance, that the condescension, which might have been ascribed to clemency, was the effect of weakness or fear. She delivered herself, her son Valentinian, and the Western empire into the hands of an insolent subject; nor could Placidia protect the son-in-law of Boniface, the virtuous and faithful Sebastian, from the Edition: current; Page: [41] implacable persecution, which urged him from one kingdom to another, till he miserably perished in the service of the Vandals. The fortunate Aetius, who was immediately promoted to the rank of patrician, and thrice invested with the honours of the consulship, assumed, with the title of master of the cavalry and infantry, the whole military power of the state; and he is sometimes styled, by contemporary writers, the Duke, or General, of the Romans of the West. His prudence, rather than his virtue, engaged him to leave the grandson of Theodosius in the possession of the purple; and Valentinian was permitted to enjoy the peace and luxury of Italy, while the patrician appeared in the glorious light of a hero and a patriot who supported near twenty years the ruins of the Western empire. The Gothic historian ingenuously confesses that Aetius was born for the salvation of the Roman republic; and the following portrait, though it is drawn in the fairest colours, must be allowed to contain a much larger proportion of truth than of flattery. “His mother was a wealthy and noble Italian, and his father Gaudentius, who held a distinguished rank in the province of Scythia, gradually rose from the station of a military domestic to the dignity of master of the cavalry. Their son, who was enrolled almost in his infancy in the guards, was given as a hostage, first to Alaric, and afterwards to the Huns; and he successively obtained the civil and military honours of the palace, for which he was equally qualified by superior merit. The graceful figure of Aetius was not above the middle stature; but his manly limbs were admirably formed for strength, beauty, and agility; and he excelled in the martial exercises of managing a horse, drawing the bow, and darting the javelin. He could patiently endure the want of food or of sleep; and his mind and body were alike capable of the most laborious Edition: current; Page: [42] efforts. He possessed the genuine courage that can despise not only dangers but injuries; and it was impossible either to corrupt, or deceive, or intimidate the firm integrity of his soul.” The Barbarians who had seated themselves in the Western provinces were insensibly taught to respect the faith and valour of the patrician Aetius. He soothed their passions, consulted their prejudices, balanced their interests, and checked their ambition. A seasonable treaty, which he concluded with Genseric, protected Italy from the depredations of the Vandals; the independent Britons implored and acknowledged his salutary aid; the Imperial authority was restored and maintained in Gaul and Spain; and he compelled the Franks and the Suevi, whom he had vanquished in the field, to become the useful confederates of the republic.

From a principle of interest, as well as gratitude, Aetius assiduously cultivated the alliance of the Huns. While he resided in their tents as a hostage or an exile, he had familiarly conversed with Attila himself, the nephew of his benefactor; and the two famous antagonists appear to have been connected by a personal and military friendship, which they afterwards confirmed by mutual gifts, frequent embassies, and the education of Carpilio, the son of Aetius, in the camp of Attila. By the specious professions of gratitude and voluntary attachment, the patrician might disguise his apprehensions of the Scythian conqueror, who pressed the two empires with his innumerable armies. His demands were obeyed or eluded. When he claimed the spoils of a vanquished city, some vases of gold, which had been fraudulently embezzled, the civil and military governors of Noricum were immediately Edition: current; Page: [43] despatched to satisfy his complaints; and it is evident from their conversation with Maximin and Priscus in the royal village, that the valour and prudence of Aetius had not saved the Western Romans from the common ignominy of tribute. Yet his dexterous policy prolonged the advantages of a salutary peace, and a numerous army of Huns and Alani, whom he had attached to his person, was employed in the defence of Gaul. Two colonies of these Barbarians were judiciously fixed in the territories of Valence and Orleans; and their active cavalry secured the important passages of the Rhone and of the Loire. These savage allies were not indeed less formidable to the subjects than to the enemies of Rome. Their original settlement was enforced with the licentious violence of conquest; and the province through which they marched was exposed to all the calamities of an hostile invasion. Strangers to the emperor or the republic, the Alani of Edition: current; Page: [44] Gaul were devoted to the ambition of Aetius; and, though he might suspect that, in a contest with Attila himself, they would revolt to the standard of their national king, the patrician laboured to restrain, rather than to excite, their zeal and resentment against the Goths, the Burgundians, and the Franks.

The kingdom established by the Visigoths in the southern provinces of Gaul had gradually acquired strength and maturity; and the conduct of those ambitious Barbarians, either in peace or war, engaged the perpetual vigilance of Aetius. After the death of Wallia the Gothic sceptre devolved to Theodoric, the son of the great Alaric; and his prosperous reign, of more than thirty years, over a turbulent people may be allowed to prove that his prudence was supported by uncommon vigour, both of mind and body. Impatient of his narrow limits, Theodoric aspired to the possession of Arles, the wealthy seat of government and commerce; but the city was saved by the timely approach of Aetius; and the Gothic king, who had raised the siege with some loss and disgrace, was persuaded, for an adequate subsidy, to divert the martial valour of his subjects in a Spanish war. Yet Theodoric still watched, and eagerly seized, the favourable moment of renewing his hostile attempts. The Goths besieged Narbonne, while the Belgic provinces were invaded by the Burgundians; and the public safety was threatened on Edition: current; Page: [45] every side by the apparent union of the enemies of Rome. On every side, the activity of Aetius, and his Scythian cavalry, opposed a firm and successful resistance. Twenty thousand Burgundians were slain in battle; and the remains of the nation humbly accepted a dependent seat in the mountains of Savoy. The walls of Narbonne had been shaken by the battering engines, and the inhabitants had endured the last extremities of famine, when Count Litorius, approaching in silence, and directing each horseman to carry behind him two sacks of flour, cut his way through the entrenchments of the besiegers. The siege was immediately raised; and the more decisive victory, which is ascribed to the personal conduct of Aetius himself, was marked with the blood of eight thousand Goths. But in the absence of the patrician, who was hastily summoned to Italy by some public or private interest, Count Litorius succeeded to the command; and his presumption soon discovered that far different talents are required to lead a wing of cavalry, or to direct the operations of an important war. At the head of an army of Huns, he rashly advanced to the gates of Toulouse, full of careless contempt for an enemy whom his misfortunes had rendered prudent and his situation made desperate. The predictions of the augurs had inspired Litorius with the profane confidence that he should enter the Gothic capital in triumph; and the trust which he reposed in his Pagan allies encouraged him to reject the fair conditions of peace, which were repeatedly proposed by the bishops in the name of Theodoric. The king of the Goths exhibited in his distress the edifying contrast of Christian piety and moderation; nor did he lay aside his sackcloth and ashes till he was Edition: current; Page: [46] prepared to arm for the combat. His soldiers, animated with martial and religious enthusiasm, assaulted the camp of Litorius. The conflict was obstinate; the slaughter was mutual. The Roman general, after a total defeat, which could be imputed only to his unskilful rashness, was actually led through the streets of Toulouse, not in his own, but in a hostile triumph; and the misery which he experienced, in a long and ignominious captivity, excited the compassion of the Barbarians themselves. Such a loss, in a country whose spirit and finances were long since exhausted, could not easily be repaired; and the Goths, assuming, in their turn, the sentiments of ambition and revenge, would have planted their victorious standards on the banks of the Rhone, if the presence of Aetius had not restored strength and discipline to the Romans. The two armies expected the signal of a decisive action; but the generals, who were conscious of each other’s force, and doubtful of their own superiority, prudently sheathed their swords in the field of battle; and their reconciliation was permanent and sincere. Theodoric, king of the Visigoths, appears to have deserved the love of his subjects, the confidence of his allies, and the esteem of mankind. His throne was surrounded by six valiant sons, who were educated with equal care in the exercises of the Barbarian camp and in those of the Gallic schools; from the study of the Roman Edition: current; Page: [47] jurisprudence, they acquired the theory, at least, of law and justice; and the harmonious sense of Virgil contributed to soften the asperity of their native manners. The two daughters of the Gothic king were given in marriage to the eldest sons of the kings of the Suevi and of the Vandals, who reigned in Spain and Africa; but these illustrious alliances were pregnant with guilt and discord. The queen of the Suevi bewailed the death of an husband, inhumanly massacred by her brother. The princess of the Vandals was the victim of a jealous tyrant, whom she called her father. The cruel Genseric suspected that his son’s wife had conspired to poison him; the supposed crime was punished by the amputation of her nose and ears; and the unhappy daughter of Theodoric was ignominiously returned to the court of Toulouse in that deformed and mutilated condition. This horrid act, which must seem incredible to a civilised age, drew tears from every spectator; but Theodoric was urged, by the feelings of a parent and a king, to revenge such irreparable injuries. The Imperial ministers, who always cherished the discord of the Barbarians, would have supplied the Goths with arms and ships and treasures for the African war; and the cruelty of Genseric might have been fatal to himself, if the artful Vandal had not armed, in his cause, the formidable power of the Huns. His rich gifts and pressing solicitations inflamed the ambition of Attila; and the designs of Aetius and Theodoric were prevented by the invasion of Gaul.

Edition: current; Page: [48]