THE HISTORY OF THE DECLINE AND FALL OF THE ROMAN EMPIRE

CHAPTER XLV

Reign of the Younger Justin — Embassy of the Avars — Their Settlement on the Danube — Conquest of Italy by the Lombards — Adoption and Reign of Tiberius — of Maurice — State of Italy under the Lombards and the Exarchs of Ravenna — Distress of Rome — Character and Pontificate of Gregory the First

During the last years of Justinian, his infirm mind was devoted to heavenly contemplation, and he neglected the business of the lower world. His subjects were impatient of the long continuance of his life and reign; yet all who were capable of reflection apprehended the moment of his death, which might involve the capital in tumult and the empire in civil war. Seven nephews of the childless monarch, the sons or grandsons of his brother and sister, had been educated in the splendour of a princely fortune; they had been shewn in high commands to the provinces and armies; their characters were known, their followers were zealous; and, as the jealousy of age postponed the declaration of a successor, they might expect with equal hopes the inheritance of their uncle. He expired in his palace after a reign of thirty-eight years; and the decisive opportunity was embraced by the Edition: current; Page: [2] friends of Justin, the son of Vigilantia. At the hour of midnight his domestics were awakened by an importunate crowd, who thundered at his door, and obtained admittance by revealing themselves to be the principal members of the senate. These welcome deputies announced the recent and momentous secret of the emperor’s decease; reported, or perhaps invented, his dying choice of the best beloved and most deserving of his nephews; and conjured Justin to prevent the disorders of the multitude, if they should perceive, with the return of light, that they were left without a master. After composing his countenance to surprise, sorrow, and decent modesty, Justin, by the advice of his wife Sophia, submitted to the authority of the senate. He was conducted with speed and silence to the palace; the guards saluted their new sovereign; and the martial and religious rites of his coronation were diligently accomplished. By the hands of the proper officers he was invested with the Imperial garments, the red buskins, white tunic, and purple robe. A fortunate soldier, whom he instantly promoted to the rank of tribune, encircled his neck with a military collar; four robust youths exalted him on a shield; he stood firm and erect to receive the adoration of his subjects; and their choice was sanctified by the benediction of the patriarch, who imposed the diadem on the head of an orthodox prince. The hipprodrome was already filled with innumerable multitudes; and no sooner did the emperor appear on his throne than the voices of the blue and the green factions were confounded in the same loyal acclamations. In the speeches which Justin addressed to the senate and people, he promised to correct the abuses which had disgraced the age of his Edition: current; Page: [3] predecessor, displayed the maxims of a just and beneficent government, and declared that, on the approaching calends of January, he would revive in his own person the name and liberality of a Roman consul. The immediate discharge of his uncle’s debts exhibited a solid pledge of his faith and generosity: a train of porters laden with bags of gold advanced into the midst of the hipprodrome, and the hopeless creditors of Justinian accepted this equitable payment as a voluntary gift. Before the end of three years his example was imitated and surpassed by the empress Sophia, who delivered many indigent citizens from the weight of debt and usury: an act of benevolence the best entitled to gratitude, since it relieves the most intolerable distress; but in which the bounty of a prince is the most liable to be abused by the claims of prodigality and fraud.

On the seventh day of his reign, Justin gave audience to the ambassadors of the Avars, and the scene was decorated to impress the Barbarians with astonishment, veneration, and terror. From the palace gate, the spacious courts and long porticos were lined with the lofty crests and gilt bucklers of the guards, who presented their spears and axes with more confidence than they would have shewn in a field of battle. The officers who exercised the power, or attended the person, of the prince were attired in their richest habits and arranged according to the military and civil order of the hierarchy. When the veil of the sanctuary was withdrawn, the ambassadors beheld the emperor of the East on his throne, beneath a canopy or dome, which was supported by four columns and crowned with a winged figure of victory. In the first emotions Edition: current; Page: [4] of surprise, they submitted to the servile adoration of the Byzantine court; but, as soon as they rose from the ground, Targetius, the chief of the embassy, expressed the freedom and pride of a Barbarian. He extolled, by the tongue of his interpreter, the greatness of the chagan, by whose clemency the kingdoms of the South were permitted to exist, whose victorious subjects had traversed the frozen rivers of Scythia, and who now covered the banks of the Danube with innumerable tents. The late emperor had cultivated, with annual and costly gifts, the friendship of a grateful monarch, and the enemies of Rome had respected the allies of the Avars. The same prudence would instruct the nephew of Justinian to imitate the liberality of his uncle, and to purchase the blessings of peace from an invincible people, who delighted and excelled in the exercise of war. The reply of the emperor was delivered in the same strain of haughty defiance, and he derived his confidence from the God of the Christians, the ancient glory of Rome, and the recent triumphs of Justinian. “The empire,” said he, “abounds with men and horses, and arms sufficient to defend our frontiers and to chastise the Barbarians. You offer aid, you threaten hostilities: we despise your enmity and your aid. The conquerors of the Avars solicit our alliance: shall we dread their fugitives and exiles? The bounty of Edition: current; Page: [5] our uncle was granted to your misery, to your humble prayers. From us you shall receive a more important obligation, the knowledge of your own weakness. Retire from our presence; the lives of ambassadors are safe; and, if you return to implore our pardon, perhaps you will taste of our benevolence.” On the report of his ambassadors, the chagan was awed by the apparent firmness of a Roman emperor, of whose character and resources he was ignorant. Instead of executing his threats against the Eastern empire, he marched into the poor and savage countries of Germany, which were subject to the dominion of the Franks. After two doubtful battles he consented to retire, and the Austrasian king relieved the distress of his camp with an immediate supply of corn and cattle. Such repeated disappointments had chilled the spirit of the Avars, and their power would have dissolved away in the Sarmatian desert, if the alliance of Alboin, king of the Lombards, had not given a new object to their arms, and a lasting settlement to their wearied fortunes.

While Alboin served under his father’s standard, he encountered in battle, and transpierced with his lance, the rival prince of the Gepidæ. The Lombards, who applauded such early prowess, requested his father with unanimous acclamations that the heroic youth, who had shared the dangers of Edition: current; Page: [6] the field, might be admitted to the feast of victory. “You are not unmindful,” replied the inflexible Audoin, “of the wise customs of our ancestors. Whatever may be his merit, a prince is incapable of sitting at table with his father till he has received his arms from a foreign and royal hand.” Alboin bowed with reverence to the institutions of his country, selected forty companions, and boldly visited the court of Turisund king of the Gepidæ, who embraced and entertained, according to the laws of hospitality, the murderer of his son. At the banquet, whilst Alboin occupied the seat of the youth whom he had slain, a tender remembrance arose in the mind of Turisund. “How dear is that place — how hateful is that person!” were the words that escaped, with a sigh, from the indignant father. His grief exasperated the national resentment of the Gepidæ; and Cunimund, his surviving son, was provoked by wine, or fraternal affection, to the desire of vengeance. “The Lombards,” said the rude Barbarian, “resemble, in figure and in smell, the mares of our Sarmatian plains.” And this insult was a coarse allusion to the white bands which enveloped their legs. “Add another resemblance,” replied an audacious Lombard; “you have felt how strongly they kick. Visit the plain of Asfeld, and seek for the bones of thy brother; they are mingled with those of the vilest animals.” The Gepidæ, a nation of warriors, started from their seats, and the fearless Alboin, with his forty companions, laid their hands on their swords. The tumult was appeased by the venerable interposition of Turisund. He saved his own honour, and the life of his guest; and, after the solemn rites of investiture, dismissed the stranger in the bloody arms of his son, the gift of a weeping parent. Alboin returned in triumph; and the Lombards, who celebrated his matchless intrepidity, were compelled to praise the virtues of an enemy. In this extraordinary Edition: current; Page: [7] visit he had probably seen the daughter of Cunimund, who soon after ascended the throne of the Gepidæ. Her name was Rosamond, an appellation expressive of female beauty, and which our own history or romance has consecrated to amorous tales. The king of the Lombards (the father of Alboin no longer lived) was contracted to the granddaughter of Clovis; but the restraints of faith and policy soon yielded to the hope of possessing the fair Rosamond, and of insulting her family and nation. The arts of persuasion were tried without success; and the impatient lover, by force and stratagem, obtained the object of his desires. War was the consequence which he foresaw and solicited; but the Lombards could not long withstand the furious assault of the Gepidæ, who were sustained by a Roman army. And, as the offer of marriage was rejected with contempt, Alboin was compelled to relinquish his prey, and to partake of the disgrace which he had inflicted on the house of Cunimund.

When a public quarrel is envenomed by private injuries, a blow that is not mortal or decisive can be productive only of a short truce, which allows the unsuccessful combatant to sharpen his arms for a new encounter. The strength of Alboin had been found unequal to the gratification of his love, ambition, and revenge; he condescended to implore the formidable aid of the chagan; and the arguments that he employed are expressive of the art and policy of the Barbarians. In the attack of the Gepidæ he had been prompted by the just desire of extirpating a people whom their alliance with the Roman empire had rendered the common enemies of the nations and the personal adversaries of the chagan. If the forces of the Avars and the Lombards should unite in this glorious quarrel, the victory was secure, and the reward inestimable: the Danube, the Hebrus, Italy, and Constantinople would be exposed, without a barrier, to their invincible Edition: current; Page: [8] arms. But, if they hesitated or delayed to prevent the malice of the Romans, the same spirit which had insulted, would pursue the Avars to the extremity of the earth. These specious reasons were heard by the chagan with coldness and disdain; he detained the Lombard ambassadors in his camp, protracted the negotiation, and by turns alleged his want of inclination, or his want of ability, to undertake this important enterprise. At length he signified the ultimate price of his alliance, that the Lombards should immediately present him with the tithe of their cattle; that the spoils and captives should be equally divided; but that the lands of the Gepidæ should become the sole patrimony of the Avars. Such hard conditions were eagerly accepted by the passions of Alboin; and, as the Romans were dissatisfied with the ingratitude and perfidy of the Gepidæ, Justin abandoned that incorrigible people to their fate, and remained the tranquil spectator of this unequal conflict. The despair of Cunimund was active and dangerous. He was informed that the Avars had entered his confines; but on the strong assurance that, after the defeat of the Lombards, these foreign invaders would easily be repelled, he rushed forwards to encounter the implacable enemy of his name and family. But the courage of the Gepidæ could secure them no more than an honourable death. The bravest of the nation fell in the field of battle; the king of the Lombards contemplated with delight the head of Cunimund, and his skull was fashioned into a cup to satiate the hatred of the conqueror, or, perhaps, to comply with the savage custom of his country. Edition: current; Page: [9] After this victory no farther obstacle could impede the progress of the confederates, and they faithfully executed the terms of their agreement. The fair countries of Walachia, Moldavia, Transylvania, and the parts of Hungary beyond the Danube were occupied, without resistance, by a new colony of Scythians; and the Dacian empire of the chagans subsisted with splendour above two hundred and thirty years. The nation of the Gepidæ was dissolved; but, in the distribution of the captives, the slaves of the Avars were less fortunate than the companions of the Lombards, whose generosity adopted a valiant foe, and whose freedom was incompatible with cool and deliberate tyranny. One moiety of the spoil introduced into the camp of Alboin more wealth than a Barbarian could readily compute. The fair Rosamond was persuaded or compelled to acknowledge the rights of her victorious lover; and the daughter of Cunimund appeared to forgive those crimes which might be imputed to her own irresistible charms.

The destruction of a mighty kingdom established the fame of Alboin. In the days of Charlemagne, the Bavarians, the Saxons, and the other tribes of the Teutonic language still repeated the songs which described the heroic virtues, the valour, liberality, and fortune of the king of the Lombards. But his ambition was yet unsatisfied, and the conqueror of Edition: current; Page: [10] the Gepidæ turned his eyes from the Danube to the richer banks of the Po and the Tiber. Fifteen years had not elapsed since his subjects, the confederates of Narses, had visited the pleasant climate of Italy; the mountains, the rivers, the highways, were familiar to their memory; the report of their success, perhaps the view of their spoils, had kindled in the rising generation the flame of emulation and enterprise. Their hopes were encouraged by the spirit and eloquence of Alboin; and it is affirmed that he spoke to their senses by producing, at the royal feast, the fairest and most exquisite fruits that grew spontaneously in the garden of the world. No sooner had he erected his standard than the native strength of the Lombards was multiplied by the adventurous youth of Germany and Scythia. The robust peasantry of Noricum and Pannonia had resumed the manners of Barbarians; and the names of the Gepidæ, Bulgarians, Sarmatians, and Bavarians may be distinctly traced in the provinces of Italy. Of the Saxons, the old allies of the Lombards, twenty thousand warriors, with their wives and children, accepted the invitation of Alboin. Their bravery contributed to his success; but the accession or the absence of their numbers was not sensibly felt in the magnitude of his host. Every mode of religion was freely practised by its respective votaries. The king of the Lombards had been educated in the Arian heresy; but the Catholics, in their public worship, were allowed to pray for his conversion; while the more stubborn Barbarians sacrificed a she-goat, or perhaps a captive, to the gods of their fathers. The Lombards and their confederates were united by their common attachment to a chief, who excelled in all the virtues and Edition: current; Page: [11] vices of a savage hero; and the vigilance of Alboin provided an ample magazine of offensive and defensive arms for the use of the expedition. The portable wealth of the Lombards attended the march; their lands they cheerfully relinquished to the Avars, on the solemn promise, which was made and accepted without a smile, that, if they failed in the conquest of Italy, these voluntary exiles should be reinstated in their former possessions.

They might have failed, if Narses had been the antagonist of the Lombards; and the veteran warriors, the associates of his Gothic victory, would have encountered with reluctance an enemy whom they dreaded and esteemed. But the weakness of the Byzantine court was subservient to the Barbarian cause; and it was for the ruin of Italy that the emperor once listened to the complaints of his subjects. The virtues of Narses were stained with avarice; and in his provincial reign of fifteen years he accumulated a treasure of gold and silver which surpassed the modesty of a private fortune. His government was oppressive or unpopular, and the general discontent was expressed with freedom by the deputies of Rome. Before the throne of Justin they boldly declared that their Gothic servitude had been more tolerable than the despotism of a Greek eunuch; and that, unless their tyrant were instantly removed, they would consult their own happiness in the choice of a master. The apprehension of a revolt was urged by the voice of envy and detraction, which had so recently triumphed over the merit of Belisarius. A new exarch, Longinus, was appointed to supersede the conqueror of Italy, and the base motives of his recall were revealed in the insulting mandate of the empress Sophia, “that he should leave to men the exercise of arms, and return to his proper station among the maidens of the palace, where Edition: current; Page: [12] a distaff should be again placed in the hand of the eunuch.” “I will spin her such a thread, as she shall not easily unravel!” is said to have been the reply which indignation and conscious virtue extorted from the hero. Instead of attending, a slave and a victim, at the gate of the Byzantine palace, he retired to Naples, from whence (if any credit is due to the belief of the times) Narses invited the Lombards to chastise the ingratitude of the prince and people. But the passions of the people are furious and changeable, and the Romans soon recollected the merits, or dreaded the resentment, of their victorious general. By the mediation of the pope, who undertook a special pilgrimage to Naples, their repentance was accepted; and Narses, assuming a milder aspect and a more dutiful language, consented to fix his residence in the Capitol. His death, though in the extreme period of old age, was unseasonable and premature, since his genius alone could Edition: current; Page: [13] have repaired the last and fatal error of his life. The reality, or the suspicion, of a conspiracy disarmed and disunited the Italians. The soldiers resented the disgrace, and bewailed the loss, of their general. They were ignorant of their new exarch; and Longinus was himself ignorant of the state of the army and the province. In the preceding years Italy had been desolated by pestilence and famine, and a disaffected people ascribed the calamities of nature to the guilt or folly of their rulers.

Whatever might be the grounds of his security, Alboin neither expected nor encountered a Roman army in the field. He ascended the Julian Alps, and looked down with contempt and desire on the fruitful plains to which his victory communicated the perpetual appellation of Lombardy. A faithful chieftain and a select band were stationed at Forum Julii, the modern Friuli, to guard the passes of the mountains. The Lombards respected the strength of Pavia, and listened to the prayers of the Trevisans; their slow and heavy multitudes proceeded to occupy the palace and city of Verona; and Milan, now rising from her ashes, was invested by the powers of Alboin five months after his departure from Pannonia. Terror preceded his march; he found everywhere, or he left, a dreary solitude; and the pusillanimous Italians presumed, without a trial, that the stranger was invincible. Escaping to lakes, or rocks, or morasses, the affrighted crowds concealed some fragments of their wealth, and delayed the moment of their servitude. Paulinus, the patriarch of Aquileia, removed his treasures, sacred and profane, to the isle of Grado, and his successors were adopted by the infant Edition: current; Page: [14] republic of Venice, which was continually enriched by the public calamities. Honoratus, who filled the chair of St. Ambrose, had credulously accepted the faithless offers of a capitulation; and the archbishop, with the clergy and nobles of Milan, were driven by the perfidy of Alboin to seek a refuge in the less accessible ramparts of Genoa. Along the maritime coast, the courage of the inhabitants was supported by the facility of supply, the hopes of relief, and the power of escape; but, from the Trentine hills to the gates of Ravenna and Rome, the inland regions of Italy became, without a battle or a siege, the lasting patrimony of the Lombards. The submission of the people invited the Barbarian to assume the character of a lawful sovereign, and the helpless exarch was confined to the office of announcing to the emperor Justin the rapid and irretrievable loss of his provinces and cities. One city, which had been diligently fortified by the Goths, resisted the arms of a new invader; and, while Italy was subdued by the flying detachments of the Lombards, the royal camp was fixed above three years before the western gate of Ticinum, or Pavia. The same courage which obtains the esteem of a civilised enemy provokes the fury of a savage, and the impatient besieger had bound himself by a tremendous oath that age, and sex, and dignity should be confounded in a general massacre. The aid of famine at length enabled him to execute his bloody vow; but, as Alboin entered the gate, his horse stumbled, fell, and could not be raised from the ground. One of his attendants was prompted by compassion, or piety, to interpret this miraculous sign of the wrath of Heaven; the conqueror paused and relented; he sheathed Edition: current; Page: [15] his sword, and, peacefully reposing himself in the palace of Theodoric, proclaimed to the trembling multitude that they should live and obey. Delighted with the situation of a city which was endeared to his pride by the difficulty of the purchase, the prince of the Lombards disdained the ancient glories of Milan; and Pavia, during some ages, was respected as the capital of the kingdom of Italy.

The reign of the founder was splendid and transient; and, before he could regulate his new conquests, Alboin fell a sacrifice to domestic treason and female revenge. In a palace near Verona, which had not been erected for the Barbarians, he feasted the companions of his arms; intoxication was the reward of valour, and the king himself was tempted by appetite, or vanity, to exceed the ordinary measure of his intemperance. After draining many capacious bowls of Rhætian or Falernian wine, he called for the skull of Cunimund, the noblest and most precious ornament of his sideboard. The cup of victory was accepted with horrid applause by the circle of the Lombard chiefs. “Fill it again with wine,” exclaimed the inhuman conqueror, “fill it to the brim; carry this goblet to the queen, and request, in my name, that she would rejoice with her father.” In an agony of grief and rage, Rosamond had strength to utter “Let the will of my lord be obeyed!” and, touching it with her lips, pronounced a silent imprecation, that the insult should be washed away in the blood of Alboin. Some indulgence might be due to the resentment of a daughter, if she had not already violated the duties of a wife. Implacable in her enmity, or inconstant in her love, the queen of Italy had stooped from the throne to the arms of a subject, and Helmichis, the king’s armour-bearer, was the secret minister of her pleasure and Edition: current; Page: [16] revenge. Against the proposal of the murder, he could no longer urge the scruples of fidelity or gratitude; but Helmichis trembled, when he revolved the danger as well as the guilt, when he recollected the matchless strength and intrepidity of a warrior whom he had so often attended in the field of battle. He pressed, and obtained, that one of the bravest champions of the Lombards should be associated to the enterprise, but no more than a promise of secrecy could be drawn from the gallant Peredeus; and the mode of seduction employed by Rosamond betrays her shameless insensibility both to honour and love. She supplied the place of one of her female attendants who was beloved by Peredeus, and contrived some excuse for darkness and silence, till she could inform her companion that he had enjoyed the queen of the Lombards, and that his own death, or the death of Alboin, must be the consequence of such treasonable adultery. In this alternative, he chose rather to be the accomplice than the victim of Rosamond, whose undaunted spirit was incapable of fear or remorse. She expected and soon found a favourable moment, when the king oppressed with wine had retired from the table to his afternoon slumbers. His faithless spouse was anxious for his health and repose; the gates of the palace were shut, the arms removed, the attendants dismissed; and Rosamond, after lulling him to rest by her tender caresses, unbolted the chamber-door, and urged the reluctant conspirators to the instant execution of the deed. On the first alarm, the warrior started from his couch; his sword, which he attempted to draw, had been fastened to the scabbard by the hand of Rosamond; and a small stool, his only weapon, could not long protect him from the spears of the assassins. The daughter of Cunimund smiled in his fall; Edition: current; Page: [17] his body was buried under the staircase of the palace; and the grateful posterity of the Lombards revered the tomb and the memory of their victorious leader.

The ambitious Rosamond aspired to reign in the name of her lover; the city and palace of Verona were awed by her power; and a faithful band of her native Gepidæ was prepared to applaud the revenge, and to second the wishes, of their sovereign. But the Lombard chiefs, who fled in the first moments of consternation and disorder, had resumed their courage and collected their powers; and the nation, instead of submitting to her reign, demanded, with unanimous cries, that justice should be executed on the guilty spouse and the murderers of their king. She sought a refuge among the enemies of her country, and a criminal who deserved the abhorrence of mankind was protected by the selfish policy of the exarch. With her daughter, the heiress of the Lombard throne, her two lovers, her trusty Gepidæ, and the spoils of the palace of Verona, Rosamond descended the Adige and the Po, and was transported by a Greek vessel to the safe harbour of Ravenna. Longinus beheld with delight the charms and the treasures of the widow of Alboin; her situation and her past conduct might justify the most licentious proposals; and she readily listened to the passion of a minister, who, even in the decline of the empire, was respected as the equal of kings. The death of a jealous lover was an easy and grateful sacrifice, and, as Helmichis issued from the bath, he received the deadly potion from the hand of his mistress. The taste of the liquor, its speedy operation, and his experience of the character of Rosamond convinced him that he was poisoned: he pointed his dagger to her breast, compelled her to drain the remainder of the cup, and expired in a few minutes, with the consolation that she could not survive to enjoy the fruits of her wickedness. The daughter of Alboin and Rosamond, with the richest spoils of the Lombards, was embarked for Constantinople; the surprising Edition: current; Page: [18] strength of Peredeus amused and terrified the Imperial court; his blindness and revenge exhibited an imperfect copy of the adventures of Samson. By the free suffrage of the nation, in the assembly of Pavia, Clepho, one of their noblest chiefs, was elected as the successor of Alboin. Before the end of eighteen months, the throne was polluted by a second murder; Clepho was stabbed by the hand of a domestic; the regal office was suspended above ten years, during the minority of his son Autharis; and Italy was divided and oppressed by a ducal aristocracy of thirty tyrants.

When the nephew of Justinian ascended the throne, he proclaimed a new era of happiness and glory. The annals of the second Justin are marked with disgrace abroad and misery at home. In the West, the Roman empire was afflicted by the loss of Italy, the desolation of Africa, and the conquests of the Persians. Injustice prevailed both in the capital and the provinces: the rich trembled for their property, the poor for their safety, the ordinary magistrates were ignorant or venal, the occasional remedies appear to have been arbitrary and violent, and the complaints of the people could no longer be silenced by the splendid names of a legislator and a conqueror. The opinion which imputes to the prince all the calamities of his times may be countenanced by the historian as a serious truth or a salutary prejudice. Yet a candid suspicion will arise that the sentiments of Justin were pure and benevolent, and that he might have filled his station without reproach, if the faculties of his mind had not been impaired by disease, which deprived the emperor of the use of his feet and confined him to the palace, a stranger to the Edition: current; Page: [19] complaints of the people and the vices of the government. The tardy knowledge of his own impotence determined him to lay down the weight of the diadem; and in the choice of a worthy substitute he shewed some symptoms of a discerning and even magnanimous spirit. The only son of Justin and Sophia died in his infancy; their daughter Arabia was the wife of Baduarius, superintendent of the palace, and afterwards commander of the Italian armies, who vainly aspired to confirm the rights of marriage by those of adoption. While the empire appeared an object of desire, Justin was accustomed to behold with jealousy and hatred his brothers and cousins, the rivals of his hopes; nor could he depend on the gratitude of those who would accept the purple as a restitution rather than a gift. Of these competitors, one had been removed by exile, and afterwards by death; and the emperor himself had inflicted such cruel insults on another, that he must either dread his resentment or despise his patience. This domestic animosity was refined into a generous resolution of seeking a successor, not in his family, but in the republic; and the artful Sophia recommended Tiberius, his faithful captain of the guards, whose virtues and fortune the emperor might cherish as the fruit of his judicious choice. The ceremony of his elevation to the rank of Cæsar, or Augustus, was performed in the portico of the palace, in the presence Edition: current; Page: [20] of the patriarch and the senate. Justin collected the remaining strength of his mind and body, but the popular belief that his speech was inspired by the Deity betrays a very humble opinion both of the man and of the times. “You behold,” said the emperor, “the ensigns of supreme power. You are about to receive them not from my hand, but from the hand of God. Honour them, and from them you will derive honour. Respect the empress your mother; you are now her son; before, you were her servant. Delight not in blood, abstain from revenge, avoid those actions by which I have incurred the public hatred, and consult the experience rather than the example of your predecessor. As a man, I have sinned; as a sinner, even in this life, I have been severely punished; but these servants (and he pointed to his ministers), who have abused my confidence and inflamed my passions, will appear with me before the tribunal of Christ. I have been dazzled by the splendour of the diadem: be thou wise and modest; remember what you have been, remember what you are. You see around us your slaves and your children; with the authority, assume the tenderness, of a parent. Love your people like yourself; cultivate the affections, maintain the discipline, of the army; protect the fortunes of the rich, relieve the necessities of the poor.” The assembly, in silence and in tears, applauded the counsels, and sympathised with the repentance, of their prince; the patriarch rehearsed the prayers of the church; Tiberius received Edition: current; Page: [21] the diadem on his knees, and Justin, who in his abdication appeared most worthy to reign, addressed the new monarch in the following words: “If you consent, I live; if you command, I die; may the God of heaven and earth infuse into your heart whatever I have neglected or forgotten.” The four last years of the emperor Justin were passed in tranquil obscurity; his conscience was no longer tormented by the remembrance of those duties which he was incapable of discharging; and his choice was justified by the filial reverence and gratitude of Tiberius.

Among the virtues of Tiberius, his beauty (he was one of the tallest and most comely of the Romans) might introduce him to the favour of Sophia; and the widow of Justin was persuaded that she should preserve her station and influence under the reign of a second and more youthful husband. But, if the ambitious candidate had been tempted to flatter and dissemble, it was no longer in his power to fulfil her expectations or his own promise. The factions of the hippodrome demanded, with some impatience, the name of their new empress; both the people and Sophia were astonished by the proclamation of Anastasia, the secret though lawful wife of the emperor Tiberius. Whatever could alleviate the disappointment of Sophia, Imperial honours, a stately palace, a numerous household, was liberally bestowed by the piety of her adopted son; on solemn occasions he attended and consulted the widow of his benefactor; but her ambition disdained the vain semblance of royalty, and the Edition: current; Page: [22] respectful appellation of mother served to exasperate, rather than appease, the rage of an injured woman. While she accepted, and repaid with a courtly smile, the fair expressions of regard and confidence, a secret alliance was concluded between the dowager empress and her ancient enemies; and Justinian, the son of Germanus, was employed as the instrument of her revenge. The pride of the reigning house supported, with reluctance, the dominion of a stranger; the youth was deservedly popular; his name, after the death of Justin, had been mentioned by a tumultuous faction; and his own submissive offer of his head, with a treasure of sixty thousand pounds, might be interpreted as an evidence of guilt, or at least of fear. Justinian received a free pardon, and the command of the Eastern army. The Persian monarch fled before his arms; and the acclamations which accompanied his triumph declared him worthy of the purple. His artful patroness had chosen the month of the vintage, while the emperor, in a rural solitude, was permitted to enjoy the pleasures of a subject. On the first intelligence of her designs he returned to Constantinople, and the conspiracy was suppressed by his presence and firmness. From the pomp and honours which she had abused, Sophia was reduced to a modest allowance; Tiberius dismissed her train, intercepted her correspondence, and committed to a faithful guard the custody of her person. But the services of Justinian were not considered by that excellent prince as an aggravation of his offences; after a mild reproof, his treason and ingratitude were forgiven; and it was commonly believed that the emperor entertained some thoughts of contracting a double alliance with the rival of his throne. The voice of an angel (such a fable was propagated) might reveal to the emperor that he should always triumph over his domestic foes; but Tiberius derived a firmer assurance from the innocence and generosity of his own mind.

With the odious name of Tiberius, he assumed the more popular appellation of Constantine and imitated the purer Edition: current; Page: [23] virtues of the Antonines. After recording the vice or folly of so many Roman princes, it is pleasing to repose, for a moment, on a character conspicuous by the qualities of humanity, justice, temperance, and fortitude; to contemplate a sovereign affable in his palace, pious in the church, impartial on the seat of judgment, and victorious, at least by his generals, in the Persian war. The most glorious trophy of his victory consisted in a multitude of captives whom Tiberius entertained, redeemed, and dismissed to their native homes with the charitable spirit of a Christian hero. The merit or misfortunes of his own subjects had a dearer claim to his beneficence, and he measured his bounty not so much by their expectations as by his own dignity. This maxim, however dangerous in a trustee of the public wealth, was balanced by a principle of humanity and justice, which taught him to abhor, as of the basest alloy, the gold that was extracted from the tears of the people. For their relief, as often as they had suffered by natural or hostile calamities, he was impatient to remit the arrears of the past, or the demands of future taxes; he sternly rejected the servile offerings of his ministers, which were compensated by tenfold oppression; and the wise and equitable laws of Tiberius excited the praise and regret of succeeding times. Constantinople believed that the emperor had discovered a treasure; but his genuine treasure consisted in the practice of liberal economy and the contempt of all vain and superfluous expense. The Romans of the East would have been happy, if the best gift of heaven, a patriot king, had been confirmed as a proper and permanent blessing. But in less than four years after the death of Justin, his worthy successor sunk into a mortal disease, which left him only sufficient time to restore the diadem, according to the tenure by which he Edition: current; Page: [24] held it, to the most deserving of his fellow-citizens. He selected Maurice from the crowd, a judgment more precious than the purple itself; the patriarch and senate were summoned to the bed of the dying prince; he bestowed his daughter and the empire; and his last advice was solemnly delivered by the voice of the quæstor. Tiberius expressed his hope that the virtues of his son and successor would erect the noblest mausoleum to his memory. His memory was embalmed by the public affliction; but the most sincere grief evaporates in the tumult of a new reign, and the eyes and acclamations of mankind were speedily directed to the rising sun.

The emperor Maurice derived his origin from ancient Rome; but his immediate parents were settled at Arabissus in Cappadocia, and their singular felicity preserved them alive to behold and partake the fortune of their august son. The youth of Maurice was spent in the profession of arms; Tiberius promoted him to the command of a new and favourite legion of twelve thousand confederates; his valour and conduct were signalised in the Persian war; and he returned to Constantinople to accept, as his just reward, the inheritance of the empire. Maurice ascended the throne at the mature age of forty-three years; and he reigned above twenty years over the East and over himself; expelling from his mind the wild democracy of passions, and establishing (according Edition: current; Page: [25] to the quaint expression of Evagrius) a perfect aristocracy of reason and virtue. Some suspicion will degrade the testimony of a subject, though he protests that his secret praise should never reach the ear of his sovereign, and some failings seem to place the character of Maurice below the purer merit of his predecessor. His cold and reserved demeanour might be imputed to arrogance; his justice was not always exempt from cruelty, nor his clemency from weakness; and his rigid economy too often exposed him to the reproach of avarice. But the rational wishes of an absolute monarch must tend to the happiness of his people; Maurice was endowed with sense and courage to promote that happiness, and his administration was directed by the principles and example of Tiberius. The pusillanimity of the Greeks had introduced so complete a separation between the offices of king and of general that a private soldier who had deserved and obtained the purple seldom or never appeared at the head of his armies. Yet the emperor Maurice enjoyed the glory of restoring the Persian monarch to his throne; his lieutenants waged a doubtful war against the Avars of the Edition: current; Page: [26] Danube; and he cast an eye of pity, of ineffectual pity, on the abject and distressful state of his Italian provinces.

From Italy the emperors were incessantly tormented by tales of misery and demands of succour, which extorted the humiliating confession of their own weakness. The expiring dignity of Rome was only marked by the freedom and energy of her complaints: “If you are incapable,” she said, “of delivering us from the sword of the Lombards, save us at least from the calamity of famine.” Tiberius forgave the reproach, and relieved the distress: a supply of corn was transported from Egypt to the Tiber; and the Roman people, invoking the name, not of Camillus, but of St. Peter, repulsed the Barbarians from their walls. But the relief was accidental, the danger was perpetual and pressing; and the clergy and senate, collecting the remains of their ancient opulence, a sum of three thousand pounds of gold, despatched the patrician Pamphronius to lay their gifts and their complaints at the foot of the Byzantine throne. The attention of the court, and the forces of the East, were diverted by the Persian war; but the justice of Tiberius applied the subsidy to the defence of the city; and he dismissed the patrician with his best advice, either to bribe the Lombard chiefs or to purchase the aid of the kings of France. Notwithstanding this weak invention, Italy was still afflicted, Rome was again besieged, and the suburb of Classe, only three miles from Ravenna, was pillaged and occupied by the troops of a simple duke of Spoleto. Maurice gave audience to a second deputation of priests and senators; the duties and the menaces of religion were forcibly urged in the letters of the Roman pontiff; and his nuncio, the deacon Gregory, was alike qualified to solicit the powers either of heaven or of the earth. The emperor adopted, with stronger effect, the measures of his predecessor; some formidable chiefs were persuaded to embrace the friendship of the Romans, and one of them, a mild and faithful Barbarian, lived and died in the service of the exarch; the passes of the Alps were Edition: current; Page: [27] delivered to the Franks; and the pope encouraged them to violate, without scruple, their oaths and engagements to the misbelievers. Childebert, the great-grandson of Clovis, was persuaded to invade Italy by the payment of fifty thousand pieces; but, as he had viewed with delight some Byzantine coin of the weight of one pound of gold, the king of Austrasia might stipulate that the gift should be rendered more worthy of his acceptance by a proper mixture of these respectable medals. The dukes of the Lombards had provoked by frequent inroads their powerful neighbours of Gaul. As soon as they were apprehensive of a just retaliation, they renounced their feeble and disorderly independence; the advantages of regal government, union, secrecy, and vigour were unanimously confessed; and Autharis, the son of Clepho, had already attained the strength and reputation of a warrior. Under the standard of their new king, the conquerors of Italy withstood three successive invasions, one of which was led by Childebert himself, the last of the Merovingian race who descended from the Alps. The first expedition was defeated by the jealous animosity of the Franks and Alemanni. In the second they were vanquished in a bloody battle, with more loss and dishonour than they had sustained since the foundation of their monarchy. Impatient for revenge, they returned a third time with accumulated force, and Autharis yielded to the fury of the torrent. The troops and treasures of the Lombards were distributed in the walled towns between the Alps and the Apennine. A nation less sensible of danger than of fatigue and delay soon murmured against the folly of their twenty commanders; and the hot vapours of an Italian sun infected with disease those tramontane bodies which had already suffered the vicissitudes of intemperance and famine. The powers that were inadequate to the conquest, were more than sufficient for the desolation, of the country; nor could the trembling natives distinguish between their enemies and their deliverers. If the junction of the Merovingian and Imperial forces had been effected in the Edition: current; Page: [28] neighbourhood of Milan, perhaps they might have subverted the throne of the Lombards; but the Franks expected six days the signal of a flaming village, and the arms of the Greeks were idly employed in the reduction of Modena and Parma, which were torn from them after the retreat of their Transalpine allies. The victorious Autharis asserted his claim to the dominion of Italy. At the foot of the Rhætian Alps, he subdued the resistance, and rifled the hidden treasures, of a sequestered island in the lake of Comum. At the extreme point of Calabria, he touched with his spear a column on the sea-shore of Rhegium, proclaiming that ancient land-mark to stand the immoveable boundary of his kingdom.

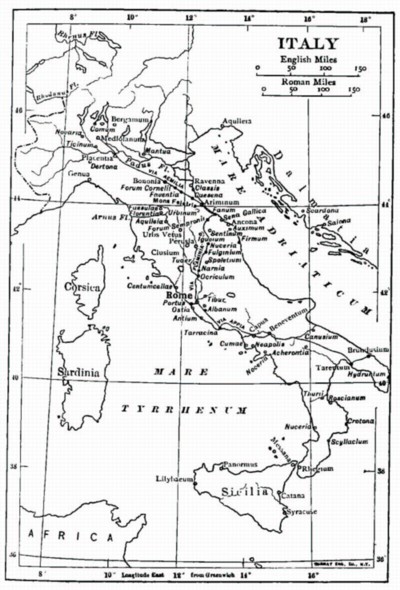

During a period of two hundred years, Italy was unequally divided between the kingdom of the Lombards and the exarchate of Ravenna. The offices and professions, which the jealousy of Constantine had separated, were united by the indulgence of Justinian; and eighteen successive exarchs were invested, in the decline of the empire, with the full remains of civil, of military, and even of ecclesiastical power. Their immediate jurisdiction, which was afterwards consecrated as the patrimony of St. Peter, extended over the modern Romagna, the marshes or valleys of Ferrara and Commachio, five maritime cities from Rimini to Ancona, Edition: current; Page: [29] and a second, inland Pentapolis, between the Hadriatic coast and the hills of the Apennine. Three subordinate provinces, of Rome, of Venice, and of Naples, which were divided by hostile lands from the palace of Ravenna, acknowledged, both in peace and war, the supremacy of the exarch. The duchy of Rome appears to have included the Tuscan, Sabine, and Latian conquests, of the first four hundred years of the city, and the limits may be distinctly traced along the coast, from Civita Vecchia to Terracina, and with the course of the Tiber from Ameria and Narni to the port of Ostia. The numerous islands from Grado to Chiozza composed the infant dominion of Venice; but the more accessible towns on the continent were overthrown by the Lombards, who beheld with impotent fury a new capital rising from the waves. The power of the dukes of Naples was circumscribed by the bay and the adjacent isles, by the hostile territory of Capua, and by the Roman colony of Amalphi, whose industrious citizens, by the invention of the mariner’s compass, have unveiled the face of the globe. The three islands of Sardinia, Corsica, and Sicily still adhered to the empire; and the acquisition of the farther Calabria removed the land-mark of Autharis from the shore of Rhegium to the isthmus of Consentia. In Sardinia, the savage mountaineers preserved the liberty and religion of their ancestors; but the husbandmen of Sicily were chained to their rich and cultivated soil. Rome was oppressed by the iron sceptre of the exarchs, and a Greek, perhaps an eunuch, insulted with impunity the ruins of the Capitol. But Naples soon acquired the privilege of electing her own dukes; the independence of Amalphi was Edition: current; Page: [30] the fruit of commerce; and the voluntary attachment of Venice was finally ennobled by an equal alliance with the Eastern empire. On the map of Italy, the measure of the exarchate occupies a very inadequate space, but it included an ample proportion of wealth, industry, and population. The most faithful and valuable subjects escaped from the Barbarian yoke; and the banners of Pavia and Verona, of Milan and Padua, were displayed in their respective quarters by the new inhabitants of Ravenna. The remainder of Italy was possessed by the Lombards; and from Pavia, the royal seat, their kingdom was extended to the east, the north, and the west, as far as the confines of the Avars, the Bavarians, and the Franks of Austrasia and Burgundy. In the language of modern geography, it is now represented by the Terra Firma of the Venetian republic, Tyrol, the Milanese, Piedmont, the coast of Genoa, Mantua, Parma, and Modena, the grand duchy of Tuscany, and a large portion of the ecclesiastical state from Perugia to the Hadriatic. The dukes, and at length the princes, of Beneventum survived the monarchy, and propagated the name of the Lombards. From Capua to Tarentum, they reigned near five hundred years over the greatest part of the present kingdom of Naples.

In comparing the proportion of the victorious and the vanquished Edition: current; Page: [none] Edition: current; Page: [31] people, the change of language will afford the most probable inference. According to this standard it will appear that the Lombards of Italy, and the Visigoths of Spain, were less numerous than the Franks or Burgundians; and the conquerors of Gaul must yield, in their turn, to the multitude of Saxons and Angles who almost eradicated the idioms of Britain. The modern Italian has been insensibly formed by the mixture of nations; the awkwardness of the Barbarians in the nice management of declensions and conjugations reduced them to the use of articles and auxiliary verbs; and many new ideas have been expressed by Teutonic appellations. Yet the principal stock of technical and familiar words is found to be of Latin derivation; and, if we were sufficiently conversant with the obsolete, the rustic, and the municipal dialects of ancient Italy, we should trace the origin of many terms which might, perhaps, be rejected by the classic purity of Rome. A numerous army constitutes but a small nation, and the powers of the Lombards were soon diminished by the retreat of twenty thousand Saxons, who scorned a dependent situation, and returned, after many bold and perilous adventures, to their native country. The camp of Alboin was of formidable extent, but the extent of a camp would be easily circumscribed within the limits of a city; and its martial inhabitants must be thinly scattered over the face of a large country. When Alboin descended from the Alps, he invested his nephew, the first duke of Friuli, with the command of the province and the people; but the prudent Gisulf would have declined the dangerous office, unless he had been permitted to choose, among the Edition: current; Page: [32] nobles of the Lombards, a sufficient number of families to form a perpetual colony of soldiers and subjects. In the progress of conquest, the same option could not be granted to the dukes of Brescia or Bergamo, of Pavia or Turin, of Spoleto or Beneventum; but each of these, and each of their colleagues, settled in his appointed district with a band of followers who resorted to his standard in war and his tribunal in peace. Their attachment was free and honourable: resigning the gifts and benefits which they had accepted, they might emigrate with their families into the jurisdiction of another duke; but their absence from the kingdom was punished with death, as a crime of military desertion. The posterity of the first conquerors struck a deeper root into the soil, which, by every motive of interest and honour, they were bound to defend. A Lombard was born the soldier of his king and his duke; and the civil assemblies of the nation displayed the banners, and assumed the appellation, of a regular army. Of this army, the pay and the rewards were drawn from the conquered provinces; and the distribution, which was not effected till after the death of Alboin, is disgraced by the foul marks of injustice and rapine. Many of the most wealthy Italians were slain and banished; the remainder were divided among the strangers, and a tributary obligation was imposed (under the name of hospitality) of paying to the Lombards a third part of the fruits of the earth. Within less than seventy years, this artificial system was abolished by a more simple and solid tenure. Either the Roman landlord was expelled by his strong and insolent guest; or the annual payment, a third of the produce, was Edition: current; Page: [33] exchanged by a more equitable transaction for an adequate proportion of landed property. Under these foreign masters, the business of agriculture, in the cultivation of corn, vines, and olives, was exercised with degenerate skill and industry by the labour of the slaves and natives. But the occupations of a pastoral life were more pleasing to the idleness of the Barbarians. In the rich meadows of Venetia, they restored and improved the breed of horses for which that province had once been illustrious; and the Italians beheld with astonishment a foreign race of oxen or buffaloes. The depopulation of Lombardy and the increase of forests afforded an ample range for the pleasures of the chase. That marvellous art which teaches the birds of the air to acknowledge the voice, and execute the commands, of their master had been unknown to the ingenuity of the Greeks and Romans. Scandinavia and Scythia produce the boldest Edition: current; Page: [34] and most tractable falcons; they are tamed and educated by the roving inhabitants, always on horseback and in the field. This favourite amusement of our ancestors was introduced by the Barbarians into the Roman provinces; and the laws of Italy esteem the sword and the hawk as of equal dignity and importance in the hands of a noble Lombard.

So rapid was the influence of climate and example that the Lombards of the fourth generation surveyed with curiosity and affright the portraits of their savage forefathers. Their heads were shaven behind, but the shaggy locks hung over their eyes and mouth, and a long beard represented the name and character of the nation. Their dress consisted of loose linen garments, after the fashion of the Anglo-Saxons, which were decorated, in their opinion, with broad stripes of variegated colours. The legs and feet were clothed in long hose and open sandals; and even in the security of peace a trusty sword was constantly girt to their side. Yet this strange apparel and horrid aspect often concealed a gentle Edition: current; Page: [35] and generous disposition; and, as soon as the rage of battle had subsided, the captives and subjects were sometimes surprised by the humanity of the victor. The vices of the Lombards were the effect of passion, of ignorance, of intoxication; their virtues are the more laudable, as they were not affected by the hypocrisy of social manners, nor imposed by the rigid constraint of laws and education. I should not be apprehensive of deviating from my subject if it were in my power to delineate the private life of the conquerors of Italy, and I shall relate with pleasure the adventurous gallantry of Autharis, which breathes the true spirit of chivalry and romance. After the loss of his promised bride, a Merovingian princess, he sought in marriage the daughter of the king of Bavaria; and Garibald accepted the alliance of the Italian monarch. Impatient of the slow progress of negotiation, the ardent lover escaped from his palace and visited the court of Bavaria in the train of his own embassy. At the public audience, the unknown stranger advanced to the throne, and informed Garibald that the ambassador was indeed the minister of state, but that he alone was the friend of Autharis, who had trusted him with the delicate commission of making a faithful report of the charms of his spouse. Theudelinda was summoned to undergo this important examination, and, after a pause of silent rapture, he hailed her as the queen of Italy, and humbly requested that, according to the custom of the nation, she would present a cup of wine to the first of her new subjects. By the command of her father, she obeyed; Autharis received the cup in his turn, and, in restoring it to the princess, he secretly touched her hand, and drew his own finger over his face and lips. In the evening, Theudelinda imparted to her nurse the indiscreet familiarity of the stranger, and was comforted by the assurance that such boldness could Edition: current; Page: [36] proceed only from the king her husband, who, by his beauty and courage, appeared worthy of her love. The ambassadors were dismissed; no sooner did they reach the confines of Italy than Autharis, raising himself on his horse, darted his battle-axe against a tree with incomparable strength and dexterity: “Such,” said he to the astonished Bavarians, “such are the strokes of the king of the Lombards.” On the approach of a French army, Garibald and his daughter took refuge in the dominions of their ally; and the marriage was consummated in the palace of Verona. At the end of one year, it was dissolved by the death of Autharis; but the virtues of Theudelinda had endeared her to the nation, and she was permitted to bestow, with her hand, the sceptre of the Italian kingdom.

From this fact, as well as from similar events, it is certain that the Lombards possessed freedom to elect their sovereign, and sense to decline the frequent use of that dangerous privilege. The public revenue arose from the produce of land and the profits of justice. When the independent dukes agreed that Autharis should ascend the throne of his father, they endowed the regal office with a fair moiety of their respective domains. The proudest nobles aspired to the honours of servitude near the person of their prince; he rewarded the fidelity of his vassals by the precarious gift of pensions and benefices; and atoned for the injuries of war by the rich foundation of monasteries and churches. In peace a judge, a leader in war, he never usurped the powers of a sole and absolute legislator. The king of Italy convened the national assemblies in the palace, or more probably in the fields, of Pavia; his great council was composed of the Edition: current; Page: [37] persons most eminent by their birth and dignities; but the validity, as well as the execution, of their decrees depended on the approbation of the faithful people, the fortunate army of the Lombards. About fourscore years after the conquest of Italy, their traditional customs were transcribed in Teutonic Latin, and ratified by the consent of the prince and people; some new regulations were introduced, more suitable to their present condition; the example of Rotharis was imitated by the wisest of his successors; and the laws of the Lombards have been esteemed the least imperfect of the Barbaric codes. Secure by their courage in the possession of liberty, these rude and hasty legislators were incapable of balancing the powers of the constitution or of discussing the nice theory of political government. Such crimes as threatened the life of the sovereign or the safety of the state were adjudged worthy of death; but their attention was principally confined to the defence of the person and property of the subject. According to the strange jurisprudence of the times, the guilt of blood might be redeemed by a fine; yet the high price of nine hundred pieces of gold declares a just sense of the value of a simple citizen. Less atrocious injuries, a wound, a fracture, a blow, an opprobrious word, were measured with scrupulous and almost ridiculous diligence; and the prudence of the legislator encouraged the ignoble practice of bartering honour and revenge for a pecuniary compensation. The ignorance of the Lombards, in the state of Paganism or Christianity, gave implicit credit to the malice and mischief of witchcraft; but the judges of the seventeenth century might have been instructed and confounded by the wisdom Edition: current; Page: [38] of Rotharis, who derides the absurd superstition, and protects the wretched victims of popular or judicial cruelty. The same spirit of a legislator, superior to his age and country, may be ascribed to Luitprand, who condemns, while he tolerates, the impious and inveterate abuse of duels, observing from his own experience that the juster cause had often been oppressed by successful violence. Whatever merit may be discovered in the laws of the Lombards, they are the genuine fruit of the reason of the Barbarians, who never admitted the bishops of Italy to a seat in their legislative councils. But the succession of their kings is marked with virtue and ability; the troubled series of their annals is adorned with fair intervals of peace, order, and domestic happiness; and the Italians enjoyed a milder and more equitable government than any of the other kingdoms which had been founded on the ruins of the Western empire.

Amidst the arms of the Lombards, and under the despotism of the Greeks, we again inquire into the fate of Rome, which had reached, about the close of the sixth century, the lowest period of her depression. By the removal of the seat of empire, and the successive loss of the provinces, the sources of public and private opulence were exhausted; the lofty Edition: current; Page: [39] tree, under whose shade the nations of the earth had reposed, was deprived of its leaves and branches, and the sapless trunk was left to wither on the ground. The ministers of command and the messengers of victory no longer met on the Appian or Flaminian way; and the hostile approach of the Lombards was often felt and continually feared. The inhabitants of a potent and peaceful capital, who visit without an anxious thought the garden of the adjacent country, will faintly picture in their fancy the distress of the Romans: they shut or opened their gates with a trembling hand, beheld from the walls the flames of their houses, and heard the lamentations of their brethren, who were coupled together like dogs and dragged away into distant slavery beyond the sea and the mountains. Such incessant alarms must annihilate the pleasures and interrupt the labours of a rural life; and the Campagna of Rome was speedily reduced to the state of a dreary wilderness, in which the land is barren, the waters are impure, and the air is infectious. Curiosity and ambition no longer attracted the nations to the capital of the world: but, if chance or necessity directed the steps of a wandering stranger, he contemplated with horror the vacancy and solitude of the city, and might be tempted to ask, where is the senate, and where are the people? In a season of excessive rains, the Tiber swelled above its banks, and rushed with irresistible violence into the valleys of the seven hills. A pestilential disease arose from the stagnation of the deluge, and so rapid was the contagion that fourscore persons expired in an hour in the midst of a solemn procession, which implored the mercy of heaven. A society in which marriage is encouraged and industry prevails soon repairs the accidental losses of pestilence and war; but, as the Edition: current; Page: [40] far greater part of the Romans was condemned to hopeless indigence and celibacy, the depopulation was constant and visible, and the gloomy enthusiasts might expect the approaching failure of the human race. Yet the number of citizens still exceeded the measure of subsistence; their precarious food was supplied from the harvests of Sicily or Egypt; and the frequent repetition of famine betrays the inattention of the emperor to a distant province. The edifices of Rome were exposed to the same ruin and decay; the mouldering fabrics were easily overthrown by inundations, tempests, and earthquakes; and the monks, who had occupied the most advantageous stations, exulted in their base triumph over the ruins of antiquity. It is commonly believed that Pope Gregory the First attacked the temples and mutilated the statues of the city; that, by the command of the Barbarian, the Palatine library was reduced to ashes; and that the history of Livy was the peculiar mark of his absurd and mischievous fanaticism. The writings of Gregory himself reveal his implacable aversion to the monuments of classic genius; and he points his severest censure against the profane learning of a bishop who taught the art of grammar, studied the Latin poets, and pronounced, with the same voice, the praises of Jupiter and those of Christ. But the evidence of his destructive rage is doubtful and recent; the Temple of Peace or the Theatre of Marcellus have been demolished by the slow operation of ages; and a formal proscription would have multiplied the copies of Virgil and Edition: current; Page: [41] Livy in the countries which were not subject to the ecclesiastical dictator.

Like Thebes, or Babylon, or Carthage, the name of Rome might have been erased from the earth, if the city had not been animated by a vital principle, which again restored her to honour and dominion. A vague tradition was embraced, that two Jewish teachers, a tent-maker and a fisherman, had formerly been executed in the circus of Nero; and at the end of five hundred years their genuine or fictitious relics were adored as the palladium of Christian Rome. The pilgrims of the East and West resorted to the holy threshold; but the shrines of the apostles were guarded by miracles and invisible terrors; and it was not without fear that the pious Catholic approached the object of his worship. It was fatal to touch, it was dangerous to behold, the bodies of the saints; and those who from the purest motives presumed to disturb the repose of the sanctuary were affrighted by visions or punished with sudden death. The unreasonable request of an empress, who wished to deprive the Romans of their sacred treasure, the head of St. Paul, was rejected with the deepest abhorrence; and the pope asserted, most probably with truth, that a linen which had been sanctified in the neighbourhood of his body, or the filings of his chain, which it was sometimes easy and sometimes impossible to obtain, possessed an equal degree of miraculous virtue. But the Edition: current; Page: [42] power as well as virtue of the apostles resided with living energy in the breast of their successors; and the chair of St. Peter was filled under the reign of Maurice by the first and greatest of the name of Gregory. His grandfather Felix had himself been pope, and, as the bishops were already bound by the law of celibacy, his consecration must have been preceded by the death of his wife. The parents of Gregory, Sylvia and Gordian, were the noblest of the senate and the most pious of the church of Rome; his female relations were numbered among the saints and virgins; and his own figure with those of his father and mother were represented near three hundred years in a family portrait, which he offered to the monastery of St. Andrew. The design and colouring of this picture afford an honourable testimony that the art of painting was cultivated by the Italians of the sixth century; but the most abject ideas must be entertained of their taste and learning, since the epistles of Gregory, his sermons, and his dialogues are the work of a man who was Edition: current; Page: [43] second in erudition to none of his contemporaries; his birth and abilities had raised him to the office of prefect of the city, and he enjoyed the merit of renouncing the pomp and vanities of this world. His ample patrimony was dedicated to the foundation of seven monasteries, one in Rome, and six in Sicily; and it was the wish of Gregory that he might be unknown in this life and glorious only in the next. Yet his devotion, and it might be sincere, pursued the path which would have been chosen by a crafty and ambitious statesman. The talents of Gregory, and the splendour which accompanied his retreat, rendered him dear and useful to the church; and implicit obedience has been always inculcated as the first duty of a monk. As soon as he had received the character of deacon, Gregory was sent to reside at the Byzantine court, the nuncio or minister of the apostolic see; and he boldly assumed, in the name of St. Peter, a tone of independent dignity, which would have been criminal and dangerous in the most illustrious layman of the empire. He returned to Rome with a just increase of reputation, and, after a short exercise of the monastic virtues, he was dragged from the cloister to the papal throne, by the unanimous voice of the clergy, the senate, and the people. He alone resisted, Edition: current; Page: [44] or seemed to resist, his own elevation; and his humble petition that Maurice would be pleased to reject the choice of the Romans could only serve to exalt his character in the eyes of the emperor and the public. When the fatal mandate was proclaimed, Gregory solicited the aid of some friendly merchants to convey him in a basket beyond the gates of Rome, and modestly concealed himself some days among the woods and mountains, till his retreat was discovered, as it is said, by a celestial light.

The pontificate of Gregory the Great, which lasted thirteen years six months and ten days, is one of the most edifying periods of the history of the church. His virtues, and even his faults, a singular mixture of simplicity and cunning, of pride and humility, of sense and superstition, were happily suited to his station and to the temper of the times. In his rival, the patriarch of Constantinople, he condemned the antichristian title of universal bishop, which the successor of St. Peter was too haughty to concede, and too feeble to assume; and the ecclesiastical jurisdiction of Gregory was confined to the triple character of bishop of Rome, primate of Italy, and apostle of the West. He frequently ascended the pulpit, and kindled, by his rude though pathetic eloquence, the congenial passions of his audience; the language of the Jewish prophets was interpreted and applied; and the minds of the people, depressed by their present calamities, were directed to the hopes and fears of the invisible world. His precepts and example defined the model of the Roman liturgy, the distribution of the parishes, the calendar of festivals, the order of processions, the service of the priests and deacons, the variety and change of sacerdotal garments. Edition: current; Page: [none] Edition: current; Page: [45] Till the last days of his life, he officiated in the canon of the mass, which continued above three hours; the Gregorian chant has preserved the vocal and instrumental music of the theatre; and the rough voices of the Barbarians attempted to imitate the melody of the Roman school. Experience had shewn him the efficacy of these solemn and pompous rites, to soothe the distress, to confirm the faith, to mitigate the fierceness, and to dispel the dark enthusiasm of the vulgar, and he readily forgave their tendency to promote the reign of priesthood and superstition. The bishops of Italy and the adjacent islands acknowledged the Roman pontiff as their special metropolitan. Even the existence, the union, or the translation of episcopal seats was decided by his absolute discretion; and his successful inroads into the provinces of Greece, of Spain, and of Gaul might countenance the more lofty pretensions of succeeding popes. He interposed to prevent the abuses of popular elections; his jealous care maintained the purity of faith and discipline; and the apostolic shepherd assiduously watched over the faith and discipline of the subordinate pastors. Under his reign, the Arians of Italy and Spain were reconciled to the Catholic church, and the conquest of Britain reflects less glory on the name of Cæsar than on that of Gregory the First. Instead of six legions, forty monks were embarked for that distant island, and the Edition: current; Page: [46] pontiff lamented the austere duties which forbade him to partake the perils of their spiritual warfare. In less than two years he could announce to the archbishop of Alexandria that they had baptised the king of Kent with ten thousand of his Anglo-Saxons, and that the Roman missionaries, like those of the primitive church, were armed only with spiritual and supernatural powers. The credulity or the prudence of Gregory was always disposed to confirm the truths of religion by the evidence of ghosts, miracles, and resurrections; and posterity has paid to his memory the same tribute which he freely granted to the virtue of his own or the preceding generation. The celestial honours have been liberally bestowed by the authority of the popes, but Gregory is the last of their own order whom they have presumed to inscribe in the calendar of saints.

Their temporal power insensibly arose from the calamities of the times; and the Roman bishops, who have deluged Europe and Asia with blood, were compelled to reign as the ministers of charity and peace. I. The church of Rome, as it has been formerly observed, was endowed with ample possessions in Italy, Sicily, and the more distant provinces; and her agents, who were commonly subdeacons, had acquired a civil, and even criminal, jurisdiction over their tenants and husbandmen. The successor of St. Peter administered his patrimony with the temper of a vigilant and moderate landlord; and the epistles of Gregory are Edition: current; Page: [47] filled with salutary instructions to abstain from doubtful or vexatious lawsuits, to preserve the integrity of weights and measures, to grant every reasonable delay, and to reduce the capitation of the slaves of the glebe, who purchased the right of marriage by the payment of an arbitrary fine. The rent or the produce of these estates was transported to the mouth of the Tiber, at the risk and expense of the pope; in the use of wealth he acted like a faithful steward of the church and the poor, and liberally applied to their wants the inexhaustible resources of abstinence and order. The voluminous account of his receipts and disbursements was kept above three hundred years in the Lateran, as the model of Christian economy. On the four great festivals, he divided their quarterly allowance to the clergy, to his domestics, to the monasteries, the churches, the places of burial, the alms-houses, and the hospitals of Rome, and the rest of the diocese. On the first day of every month, he distributed to the poor, according to the season, their stated portion of corn, wine, cheese, vegetables, oil, fish, fresh provisions, cloths, and money; and his treasurers were continually summoned to satisfy, in his name, the extraordinary demands of indigence and merit. The instant distress of the sick and helpless, of strangers and pilgrims, was relieved by the bounty of each day, and of every hour; nor would the pontiff indulge himself in a frugal repast, till he had sent the dishes from his own table to some objects deserving of his compassion. The misery of the times had reduced the nobles and matrons of Rome to accept, without a blush, the benevolence of the church; three thousand virgins received their food and raiment from the hand of Edition: current; Page: [48] their benefactor; and many bishops of Italy escaped from the Barbarians to the hospitable threshold of the Vatican. Gregory might justly be styled the Father of his country; and such was the extreme sensibility of his conscience that, for the death of a beggar who had perished in the streets, he interdicted himself during several days from the exercise of sacerdotal functions. II. The misfortunes of Rome involved the apostolical pastor in the business of peace and war; and it might be doubtful to himself whether piety or ambition prompted him to supply the place of his absent sovereign. Gregory awakened the emperor from a long slumber, exposed the guilt or incapacity of the exarch and his inferior ministers, complained that the veterans were withdrawn from Rome for the defence of Spoleto, encouraged the Italians to guard their cities and altars, and condescended, in the crisis of danger, to name the tribunes and to direct the operations of the provincial troops. But the martial spirit of the pope was checked by the scruples of humanity and religion; the imposition of tribute, though it was employed in the Italian war, he freely condemned as odious and oppressive; whilst he protected, against the Imperial edicts, the pious cowardice of the soldiers who deserted a military for a monastic life. If we may credit his own declarations, it would have been easy for Gregory to exterminate the Lombards by their domestic factions, without leaving a king, a duke, or a count, to save that unfortunate nation from the vengeance of their foes. As a Christian bishop, he preferred the salutary offices of peace; his mediation appeased the tumult of arms; but he was too conscious of the arts of the Greeks, and the passions of the Lombards, to engage his sacred promise for the observance of the truce. Disappointed in the hope of a general and lasting treaty, he presumed to save his country without the consent of the emperor or the exarch. The sword of the enemy was suspended over Rome: it was averted by the mild eloquence and seasonable gifts of Edition: current; Page: [49] the pontiff, who commanded the respect of heretics and barbarians.

The merits of Gregory were treated by the Byzantine court with reproach and insult; but in the attachment of a grateful people he found the purest reward of a citizen and the best right of a sovereign.

Edition: current; Page: [50]

CHAPTER XLVI

Revolutions of Persia after the Death of Chosroes or Nushirvan — His Son Hormouz, a Tyrant, is deposed — Usurpation of Bahram — Flight and Restoration of Chosroes II. — His Gratitude to the Romans — The Chagan of the Avars — Revolt of the Army against Maurice — His Death — Tyranny of Phocas — Elevation of Heraclius — The Persian War — Chosroes subdues Syria, Egypt, and Asia Minor — Siege of Constantinople by the Persians and Avars — Persian Expeditions — Victories and Triumph of Heraclius