CONTENTS

- SPAIN

- En Torno a la Funcion del Capital

Joaquín Reig, Doctor en Derecho, Madrid . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

- SOUTH AFRICA

- Reflections on the Keynesian Episode

W. H. Hutt, Distinguished Visiting Professor, University of Dallas, Texas; Professor Emeritus, University of Capetown . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

- Ludwig von Mises and the Market Process

L. M. Lachmann, Professor of Economics and Economic History, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

- UNITED STATES

- Values, Prices and Statistics

Bettina Bien, Member of the Senior Staff, Foundation for Economic Education, New York . . . . . . . . . .

- The Tax System and a Free Society

Oswald Brownlee, Professor of Economics, University of Minnesota . . . .

- How “Should” Common-Access Facilities Be Financed?

James M. Buchanan, Professor of Economics and General Director of the Center for Study of Public Choice, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

- Edition: current; Page: [v]

Pitfalls in Planning: Veterans' Housing after World War II

Marshall R. Colberg, Professor of Economics, Florida State University . . .

- Presents for the Poor

R. L. Cunningham, Professor of Philosophy, University of San Francisco . .

- Restrictions on International Trade: Why Do They Persist?

W. Marshall Curtiss, Executive Secretary, Foundation for Economic Education, New York . . . . . . . . . .

- “human action”

E. W. Dykes, Lawrence, Dykes, Good-enberger and Bower, Canton, Ohio . . .

- The Genius of Mises' Insights

Lawrence Fertig, Economic Columnist and Author, New York . . . . . . .

- On Behalf of Profits

Percy L. Greaves, Jr., Armstrong Professor of Economics, University of Plano, Texas . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

- Tax Reform: Two Ways to Progress

C. Lowell Harriss, Professor of Economics, Columbia University; Economic Consultant, Tax Foundation of New York . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

- The Future of Capitalism

Henry Hazlitt, Wilton, Connecticut . .

- Prices and Property Rights in the Command Economy

Arthur Kemp, Charles M. Stone Professor

Edition: current; Page: [vi]

of Money and Credit, Claremont Men's College, California . . . . . . .

- The Inevitable Bankruptcy of the Socialist State

Howard E. Kershner, Chairman, Christian Freedom Foundation, California . .

- Entrepreneurship and the Market Approach to Development

Israel M. Kirzner, Professor of Economics, New York University . . . . .

- The New Science of Freedom

George Koether, Rainbow Ridge, Virgin Islands . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

- Financing, Correcting, and Adjustment: Three Ways to Deal with an Imbalance of Payments

Fritz Machlup, Walker Professor of Economics and International Finance, Princeton University . . . . . . . . .

- On Protecting One's Self from One's Friends

Don Paarlberg, Hillenbrand Professor of Agricultural Economics, Purdue University (on Leave) . . . . . . . . . .

- Recollections Re a Kindred Spirit

William A. Paton, Professor Emeritus of Economics, University of Michigan . . .

- Ludwig von Mises

William H. Peterson, Princeton, New Jersey; Former Student and Teaching Associate of Professor Mises . . . . .

- Edition: current; Page: [vii]

The Economic-Power Syndrome Sylvester Petro, Professor of Law, New York University . . . . . . . . . .

- Ownership as a Social Function

Paul L. Poirot, Managing Editor, The Freeman, Irvington-on-Hudson, New York . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

- To Abdicate or Not

Leonard E. Read, President, Foundation for Economic Education, New York . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

- The Book in the Market Place

Henry Regnery, Chairman of the Board, Henry Regnery Company, Chicago . . .

- Lange, Mises and Praxeology: The Retreat from Marxism

Murray N. Rothbard, Professor of Economics, Polytechnic Institute of Brooklyn . . . . . . . . . . . . .

- The Production and Exchange of Used Body Parts

Simon Rottenberg, Professor of Economics, University of Massachusetts . .

- The Education of Lord Acton

Robert L. Schuettinger, Assistant Professor of Political Science, Lynchburg College, Virginia . . . . . . . . . . .

- Chicago Monetary Tradition in the Light of Austrian Theory

Hans F. Sennholz, Professor of Economics, Grove City College, Pennsylvania

- Hubris and Environmental Variance

Joseph J. Spengler, James B. Duke Professor

Edition: current; Page: [viii]

of Economics, Duke University, North Carolina . . . . . . . . . . .

- An Application of Economics in Biology

Gordon Tullock, Professor of Economics and Public Choice, Virgmia Polytechnic Institute and State University . .

- What Mises Did for Me

John V. Van Sickle, Boulder, Colorado; Professor Emeritus of Wabash College

- Economics in a Changing World

G. C. Wiegand, Professor of Economics, Southern Illinois University . . . . . .

- Can a Liberal Be an Equalitarian?

Leland B. Yeager, Professor of Economics, University of Virginia . . . . .

- URUGUAY

- The Political Economy of Nostalgia

Ramon Diaz, former Professor of Political Economy, University of Uruguay . .

Edition: current; Page: [1]

En Torno a la Funcion del Capital

Joaquín Reig

(Algunas de las cosas que Mises nos enseñó)

“Marx utilizó, en sentido peyorativo, desde Juego, las palabras capitalismo, capital y capitalistas, al igual que hoy la mayor parte de las gentes las emplean ... Tales vocablos, no obstante, reflejan con extraordinaria justeza qué fué aquello que, primordialmente, provocó el maravilloso progreso de los dos últimos siglos, es decir, esa incesante mejoría del nivel de vida de unas masas humanas en contínuo crecimiento.” (Mises).

Lo que los hombres lamentamos—sin, desde luego, la mayoría saberlo—es una capitalización insuficiente; nos quejamos de no disponer, en cuantía bastante, de aquellos medios necesarios para alcanzar los objetivos anhelados. Consumir más—a no dudar, lo deseado—exige mayor producción. Para ampliar ésta, sin embargo, preciso resulta disponer de supletorios instrumentos, merced a los cuales cabrá mejor aprovechar los recursos naturales disponibles. La obtención de tales factores presupone anterior ahorro: haber destinado parte de la previa actividad humana a la preparación de esos bienes económicos—capital—que el incremento de la producción requiere. Los problemas de nuestro tiempo, como desde el albor de la humanidad sucede, sólo a base de más capital pueden ser eficazmente abordados.

Edition: current; Page: [2]

Lo dramático, sin embargo, es que el capital sólo aparece bajo una economía de mercado; en un orden social donde exista la propiedad privada de los medios de producción, los cuales, consecuentemente, pueden ser contratados, registrando así sus respectivos y correspondientes precios. El régimen colectivista tiene bienes de capital, pero no sabe qué sea capital. Porque el capital no es una cosa material, sino un concepto intelectual; es, en definitiva, el valor de mercado de los medios de producción que el sujeto económico tiene a su disposición. Y no son los factores disponibles lo importante para la producción, sino la utilidad social, el valor, en cada supuesto concreto, de aquéllos.

Hay minas, terrenos, aguas y múltiples riquezas naturales inexplotables por carecerse de los elementos complementarios necesarios para su aprovechamiento. No constituyen aquellos elementos capital; lo serán sólo cuando surjan, gracias al ahorro, los medios que permitan su explotación. El nivel de vida de un país no depende de las riquezas naturales que posea, sino de la cuantía del capital disponible. Véase el caso de Suiza, en un sentido, y el de China o la India, en el contrario.

Por eso, factores de producción, que, en cierto momento, fueron capital, pueden, después, dejar de serlo (con independencia de su desgaste). Supongamos una empresa ferroviaria, hace treinta años, con un parque de cien locomotoras de vapor, es decir, las, entonces, predominantemente empleadas. Constituían ellas, a la sazón, un capital importante. Esa misma empresa, ahora, con idénticas locomotoras, hallaríase, en cambio, totalmente descapitalizada, ya que, según todo el mundo sabe, dicho tipo de tracción resulta antieconómico, inexplotable. Las locomotoras de vapor, consecuentemente, carecen hoy de valor, de interés social, ya no son capital, aunque ayer lo fueron.

Ese instrumento mental que es el capital -basado en los precios del mercado- nos indica qué, cómo y cuánto producir, Si la organización social imperante impide recurrir a tal herramienta intelectual, la actividad económica toda se

Edition: current; Page: [3]

hunde en insoluble caos.

“Los empresarios -nos enseña Mises- invierten el capital, ahorrado por terceros, procurando satisfacer, del modo mejor, las más urgentes y todavía no satisfechas necesidades de los consumidores. Junto a los investigadores, dedicados a perfeccionar los métodos de producción, desempeñan los empresarios, inmediatamente después de quienes supieron ahorrar, papel decisivo en el progreso económico. Los demás no hacemos sino beneficiarnos de la actuación de aquéllos. Cualquiera que sea nuestra actividad, somo simples beneficiarios de un progreso al que en nada contribuimos.

Lo carac terístico de la economía de mercado es beneficiar a la inmensa mayoría, que recibe la parte del león de unas mejoras conseguidas gracias exclusivamente al actuar de aquellos tres grupos rectores, integrados por quienes ahorran, quienes invierten y quienes arbitran fórmulas nuevas que permiten mejor explotar los bienes disponibles.”

Estas lucubraciones en torno al concepto de capital nos hacen ver el defecto básico del socialismo. El régimen colectivista, por definición, exige que ningún factor de producción quede en manos privadas. Dichos bienes son todos propiedad del estado o de cualquier otro único ente colectivo; no pueden ser contratados en ningún mercado y, por tanto, carecen de precios que reflejen su respectivo interés social.

Plantéase, en esta situación, al rector de la comunidad socialista el azorante problema de determinar cómo producir aquello que él mismo -por sí y ante sí, car tel est notre bon plaisir- haya decidido sea lo que más conviene elaborar. Se puede, desde luego, fabricar escupideras de oro o juguetes de molibdeno para los niños, cuando se desconoce el precio del oro y del molibdeno.

Edition: current; Page: [4]

Mises sitúa la cuestión con su habitual claridad:

“Una ciudad puede ser abastecida de agua potable mediante transportar el líquido elemento desde lejanos manantiales a través de acueductos -método empleado desde los tiempos más remotos- o bien purificando, por unos u otros medios, el agua insalubre existente en la localidad. Pero ¿por qué no producir agua sintética? La técnica moderna ha tiempo resolvió cuantas dificultades tal producción plantea. El hombre medio, dominado siempre por su inercia mental, limitaríase a calificar la idea de absurda. La única razón, sin embargo, por la que no producimos hoy agua potable sintética -aunque tal vez mañana lo hagamos- es porque el cálculo económico nos advierte que se trata del procedimiento más caro de todos los conocidos. Eliminado el cálculo económico, la elección racional deviene imposible.”

La contabilidad de capital nos permite saber si se gana o se pierde en la actividad económica; advertimos si lo que producimos vale más o vale menos que los factores invertidos. En el primera caso, nuestra actuación tiene interés social y conviene proseguirla; en el segundo, no, y debemos orientar el esfuerzo en otra dirección.

El dictador socialista, cercado siempre por las tinieblas que el propio sistema engendra, jamás puede servirse de esas clarísimas directrices con las que el mercado, a diario, en bien de los consumidores, guía al productor capitalista. La ceguera de aquél, sin embargo, hoy en día, todavía no es absoluta, pues, mal que bien, se orienta contemplando la actuación del mundo llamado capitalista. Se entera, así, de que no debe producir agua sintética, ni utilizar locomotoras de vapor, pero ha de cometer, no obstante, errores garrafales, por buena que su intención sea -cosa que jamás se discute- pues las situaciones no son nunca idénticas y cada problema económico hay que resolverlo según el momento específico y la circunstancia particular requiera.

Esta intrínseca falla del socialismo, descubierta por Mises hace cincuenta años, aunque al principio fué ampliamente discutida, ya nadie la pone en duda. Los socialistas informados -que, por desgracia, son pocos- desde hace veinticinco

Edition: current; Page: [5]

años no se atreven a discutir con el maestro; pretenden simplemente escamotear el tema. Se acabó para el socialismo el blasonar de científico; se ha transformado, simplemente, en una secta religiosa, cuyos dogmas no deben ser jamás sometidos al análisis lógico. El superior no se equivoca nunca, pues es -no lo dude nadie-infinitamente sabio y bondadoso. He ahí el absurdo mito en que todo el edificio intelectual socialista se apoya.

“Las gentes -nos recuerda Mises- frecuentemente califican de religión al socialismo. Y, ciertamente, lo es; es la religión de la autodivinización. El Estado y el Gobierno al que los planificadores aluden, el Pueblo de los nacionalistas, la Sociedad de los marxistas y la Humanidad de los positivistas son distintos nombres que adopta el dios de la nueva religión. Tales símbolos, sin embargo, tan sólo sirven para que tras ellos se oculte la personal voluntad del reformador. Asignando a su ídolo cuantos atributos los teólogos a Dios otorgan, el engreído ego se autobeatifica. También él es -piensa- infinitamente bueno, omnipotente, omnipresente, omnisciente y eterno; el único ser perfecto en este imperfecto mundo.

La economía debe rehuir el fanatismo y la sectaria ofuscación. Argumento alguno, desde luego, impresiona al fiel devoto. La más leve crítica resulta para él escandalosa y recusable blasfemia, impío ataque lanzado por gentes malvadas contra la gloria imperecedera de su deidad. La economía se interesa por la teoría socialista, no por las motivaciones psicológicas que inducen a las gentes a caer en la estatolatría.”

Una vez aprehendido el concepto, fácil es percatarse de que, mediante manipulaciones monetarias, huérfanas de ahorro y simplemente ampliadoras de la masa dineraria, no se crea capital, ni por tanto riqueza. (Si ello no fuera así, lo mejor sería arrojar, con un helicóptero, toneladas de papel moneda a lo largo y lo ancho del país).

La Administración amplía la cuantía de los medios de pago, particularmente, otorgando créditos baratos, que el mercado no concedería, ya sea a través de sus organismos,

Edition: current; Page: [6]

ya sea induciendo a ello, por unos u otros medios, a la banca. La creación de billetes tiene importancia monetaria pero, a estos efectos, podemos pasarla por alto. La banca privada, nótese incidentalmente, bajo un régimen de libertad, no puede sino limitarse a administrar, del modo más acertado posible, los factores monetarios que encuentra dados. Su propia supervivencia le veda lanzarse a ningún boom expansionista.

El bajo interés de los aludidos créditos oficiales perturba la marcha de la economía, desembocando, al cabo del tiempo, en la temida crisis económica. Dichos arbitrismos crediticios dan, en efecto, lugar a inversiones -aparentemente lucrativas, dado el bajo interés que pagan- para las que no existen, sin embargo, los requeridos factores de producción. Los que, en las producciones alentadas por el crédito fácil, son invertidos, detráense, por desgracia, de otras, más conformes con los deseos del mercado consumidor, cuyas actividades consiguientemente quedan restringidas. Y la crisis es simplemente la purga, el correctivo, que obliga a abandonar empresas disconformes con las necesidades de los compradores. En tal sentido, aquélla, como la fiebre, constituye un bien.

Dice a este respecto Mises:

“Es el proceso democrático del mercado lo que origina la crisis. Los consumidores no están conformes con el modo cómo los empresarios emplean los factores de producción. Muestran su disconformidad comprando y dejando de comprar. Los empresarios, cegados por el espejismo de unas tasas de interés artificialmente rebajadas, no han efectuado aquellas inversiones que permitirían atender del mejor modo posible las más acuciantes necesidades del público. Tales yerros quedan al descubierto en cuanto la expansión crediticia se detiene. La actitud de los consumidores obliga a los empresarios a reajustar de nuevo sus actividades al objeto de dejar atendidas en la mayor medida posible las necesidades de las gentes. Eso que denominamos depresión es precisamente el proceso liquidatorio de los errores del auge, readaptación de la producción a los deseos de los consumidores.

En la economía socialista, por el contrario, sólo cuentan los juicios de valor del gobernante; las masas no tienen medios que les permitan imponer sus preferencias. El

Edition: current; Page: [7]

dictador no se preocupa de si las gentes están o no conformes con la cuantía de lo que él acuerda dedicar al consumo y de lo que él decide reservar para ulteriores inversiones. Si la importancia de estas últimas obliga a drásticamente reducir el consumo, el pueblo pasa hambre y se aguanta. No se produce crisis alguna porque las gentes no pueden expresar su descontento. Donde no hay vida mercantil, ésta no puede ser próspera ni adversa. En tales circunstancias habrá pobreza e inanición, pero nunca crisis en el sentido que el vocablo tiene en la economía de mercado. Cuando los hombres no pueden optar ni preferir, en forma alguna cábeles protestar contra la orientación dada a las actividades productivas.”

El intervencionismo provoca siempre efectos contrarios a los que los patrocinadores del sistema aspiran a conseguir. Tal acontece, como no podía ser menos, con el intervencionismo de tipo monetario que contemplamos. Se desea, al multiplicar los medios de pago, reduciendo el interés, incrementar la producción; y lo único que se consigue es malinvertir los siempre escasos factores de producción disponibles; o sea, disminuir, al final, el valor de lo producido.

Con todos los precios sucede lo mismo. Los máximos, aquéllos por encima de los cuales no se debería comerciar, precisamente porque el bien en cuestión es considerado de grande interés social, dan lugar a que las explotaciones marginales, al devenir antieconómicas, dejen de producir, con lo que no se amplía, sino que se reduce la producción y el número de quienes efectivamente consiguen disfrutar de la tan apetecida mercancía. Hay, por tanto, mayor escasez; talmente lo que se quería evitar.

Los precios mínimos operan igual, aunque con signo contrario. Hacen aumentar, ponendo en marcha ofertas marginales, la cuantía de unos bienes que, dadas las circunstancias concurrentes, ya resultaban excesivos y cuyos precios,

Edition: current; Page: [8]

por eso mismo, declinaban. Aparecen los indisponibles excedentes, con los que nadie sabe ya qué hacer.

“Existen y han existido siempre -afirma Misespartidarios de la regulación coactiva de los precios y que, sin embargo, de modo categórico, proclaman ser partidarios de la economía de mercado. El poder público puede, en su opinión, alcanzar los fines que se propone mediante la fijación de precios, salarios y tipos de interés, sin abolir en modo alguno ni el mercado, ni la propiedad privada de los medios de producción. La regulación coactiva de los precios constituye el mejor -o más bien el único- procedimiento para conservar el régimen de empresa privada e impedir el advenimiento del socialismo. Pero indígn anse hasta el paroxismo si se les refuta y se les demuestra que la interferencia en los precios, apar te de empeorar la situación, fatalmente conduce al socialismo.”

Y esto nos lleva al problema de los salarios. Todo trabajador por cuenta ajena, como es natural, desea aumentar sus ingresos, pues quiere vivir mejor (no importa si es en el aspecto espiritual o en el material). Para elevar los salarios han sido ideados arbitrios múltiples. Pero las rentas laborales reales únicamente aumentan cuando se incrementa la productividad del laborador y esto, a no ser que el interesado desee trabajar más, sólo se consigue poniendo a disposición del operario una mayor y mejor constelación de instrumentos de producción previamente elaborados; en otras palabras, más capital.

El capital, que el ahorro crea, abre la posibilidad de iniciar nuevas actividades; crece, con ello, la demanda de trabajadores. Los salarios tienden al alza y se financia ésta, sin perjuicio para nadie, con la supletoria producción que la mayor capitalización lleva aparejada.

“La única diferencia -dice Mises- existente entre las condiciones de trabajo de la era capitalista y de la precapitalista y, aun hoy, entre los países atrasados y los occidentales, consiste en la distinta cuantía del capital disponible. El incremento per capita de este último eleva, por una parte, la utilidad marginal del trabajo y, por otra, abarata las marcancías.

Edition: current; Page: [9]

Ningún adelanto técnico cabe adoptar si previamente no ha sido ahorrado el correspondiente capital. Sólo el ahorro, la acumulación de nuevos capitales, ha permitido ir, paulatinamente, desterrando la penosa búsqueda de alimentos a que se hallaba obligado el primitivo hombre de las cavernas e implantar, en su lugar, los fecundos métodos modernos de producción. Tan trascendental mutación fué posible gracias a aquellas ideas, amparadoras de la propiedad privada de los medios de producción, que, proporcionando garantías y seguridades, permitieron la acumulación de capital.”

La coactiva elevación de las retribuciones salariales no eleva, en cambio, la renta de la masa trabajadora; loque produce es paro, en las explotaciones marginales. Se be neficia a algunos laboradores, reduciéndose los ingresos de otros hermanos suyos, quedando además inactiva una parte del capital disponible, lo que supone, en la práctica, evidente descapitalización.

Para quien haya logrado percatarse de la íntima relación entre capital y salarios y advierta las desastradas consecuencias sociales que lleva aparejada la coactiva elevación de las rentas laborales, resulta en verdad entristecedora la posición adoptada en estas materias por la opinión pública, que Mises, en gráfico pasaje, bien retrata:

“Propugnar un alza constante de la remuneración laboral -por decisión del poder público o como consecuencia de la intimidación o la fuerza de los sindicatos- constituye la esencia de la filosofía actual. Elevar los salarios más allá del límite que un mercado inadulterado señalaría, repútase medida indispensable desde el punto de vista económico, amparada además por eternas normas morales. Quien tenga la audacia de oponerse a ese dogma ético-económico veráse, de inmediato, menospreciado como imagen viva de la máxima perversidad e ignorancia. El temor, el asombro, con que las tribus primitivas contemplaban a quienquiera osara violar una norma reputada tabú, es idéntico al que traducen nuestros contemporáneos cuando alguien es lo bastante temerario como para, de algún modo, atreverse a cruzar “las líneas de piquetes”. Millones de seres exultan de gozo cuando los esquiroles reciben “su merecido castigo” de manos de los huelguistas,

Edition: current; Page: [10]

en tanto que policías, fiscales y jueces o se encierran en altiva neutralidad o, incluso, pónense del lado de quienes provocan las algaradas.”

Lo anterior nos lleva de la mano a aludir, aunque sólo sea de pasada, al tan manoseado tema del “asociacionismo laboral” y al no menos manido del “derecho de huelga”. Dos párrafos magistrales bastan a Mises para situar ambas cuestiones en sus estrictos y exactos términos:

“La esencia del problema nada tiene que ver con el “derecho de asociación”. Tan sólo se trata de dilucidar si conviene conferir a determinado grupo de ciudadanos el privilegio de impunemente recurrir a la acción violenta. Estamos ante un problema idéntico al que suscitan las actividades del Ku Klux Klan.

Incorrecto también resulta enfocar el asunto desde el ángulo del “derecho a la huelga”. No se discute el derecho a abandonar el trabajo, sino la facultad de obligar a otros -mediante la intimidación y la violencia- a holgar. Cuando los sindicatos, para justificar su actuación intimidatoria y violenta, invocan el derecho de huelga, no quedan mejor emplazados que la secta religiosa que pretendiera ampararse en la libertad de conciencia para perseguir al disidente.”

Y hablando de capital no es posible dejar de aludir a las exacciones fiscales.

Los impuestos son necesarios porque, para mantener el orden público, tal cual están las cosas, ineludible parece el Estado. La financiación del aparato estatal constituye un costo, es decir, un medio necesario para alcanzar un fin deseado. Conviene, por lo dicho, desde un punto de vista social, sufragar tal dispendio mediante contribuciones que incidan lo menos posible en el ahorro. (Los impuestos indirectos, en este sentido, provocan una tendencia al alza de los salarios y al mejoramiento del nivel de vida de las clases trabajadoras, al afectar en menor medida la creación de capital).

Edition: current; Page: [11]

Que el Estado gaste lo menos posible, una vez debidamente atendido el respeto a la ley, es siempre beneficioso para todos y particularmente para quienes gozan de menores medios, pues lo que no sea consumido por la Administración se dedicará, forzosamente, a las producciones que desde un punto de vista social más interesen.

“Cuando la ley -dice a este respecto Mises- hace prohibitivo, por ejemplo, acumular más de diez millones o ganar más de un millón al año, aparta, en determinado momento, del proceso productivo, precisamente, a aquellos indivíduos que mejor están atendiendo los deseos de los consumidores. Si una disposición de este tipo hubiera sido dictada en los Estados Unidos hace cincuenta afios, muchos de los que hoy son multimillonarios vivirían en condiciones bastante más modestas. Ahora bien, todas esas industrias, que abastecen a las masas con mercancías nunca soñadas, operarían, de haberse llegado a montar, a escala reducida, hallándose, en consecuencia, sus producciones fuera del alcance del hombre medio. Perjudica, evidentemente, a los consumidores el vedar a los empresarios más eficientes que amplíen la esfera de sus actividades, en la medida que conforman con los deseos de las gentes, deseos que éstas patentizan al adquirir los productos por aquéllos ofrecidos. Plantéase de nuevo el dilema: ¿ a quién debe corresponder la suprema decisión, a los consumidores o al jerarca? En un mercado sin trabas, el consumidor, comprando o absteniéndose de comprar, determina, en definitiva, los ingresos y la fortuna de cada uno. ¿ Es prudente investir a quienes detentan el poder con la facultad de alterar la voluntad de los consumidores?”

La falta de conocimiento popular, en estas materias, es grande. Por eso, ni aun los gobernantes más ilustrados y mejor intencionados pueden, muchas veces, aplicar medidas, altamente beneficiosas para las masas, pero que éstas airadas rechazan, sin advertir que están laborando contra sus propios intereses.

Difundir información acerca de cómo, realmente, funciona la economía, acerca de cómo opera, en definitiva, la

Edition: current; Page: [12]

actividad toda del hombre, es lo que más urgente parece. Impuestas las gentes de tales verdades, cabría, sin dificultad, reducir el gasto estatal a aquello que el mantenimiento del orden público en cada caso exigiera; evitar la creación de medios de pago con créditos de carácter político y administrativo; fomentar la capitalización, a través de un sistema impositivo que castigara lo menos posible al ahorro; desterrando, en definitiva, un intervencionismo que sólo indeseadas consecuencias acarrea y que paulatinamente nos va entregando en manos del marxismo, la más grande aberración económica jamás ideada por el hombre. Se conseguiría, así, -y esto parece lo más importante- elevar, en el mayor grado posible, el nivel de vida de todas las clases sociales, particularmente el de las de menores medios.

Dice Mises, en el último párrafo de La Acción Humana, donde parece querer condensar todo su trascendente mensaje:

“El saber acumulado por la ciencia económica forma parte fundamental de la civilización; en dicho saber se basa el industrialismo moderno y en él se han amparado cuantos triunfos morales, intelectuales, técnicos y terapéuticos ha alcanzado el hombre a lo largo de las últimas centurias. El género humano decidirá si quiere hacer uso adecuado del inapreciable tesoro de conocimientos que este acervo supone o si, por el contrario, prefiere no utilizarlo. Ahora bien, si los mortales prescinden de tan espléndidos hallazgos y siguen menospreciando tan fecundas enseñanzas, no por ello desvirtuarán la ciencia económica; se limitarán, desgraciadamente, a destruir la sociedad y a aniquilar al género humano.”

Son éstas unas pocas de las múltiples verdades con que Mises amplía nuestro conocimiento. Pero, aparte de tan invaluable ilustración, el gran legado del maestro, creo yo, consiste en habernos enseñado a muchos a pensar, es decir, a mentalmente especular con el rigor máximo y la justeza mayor que a cada uno permite su personal limitación.

N. B.—Todos los subrayados del texto son del firmante.

Edition: current; Page: [13]

Reflections on the Keynesian Episode

W. H. Hutt

In my Keynesianism-Retrospect and Prospect, 1963, I enunciated and defended the thesis that the intellectual developments for which Keynes' General Theory appeared to be responsible had caused a setback to scientific thinking about human economic relations at a crucial epoch. In doing so, I referred (in the final chapter) to a growing tendency to abandon crucial theoretical tenets in Keynes' system. Nevertheless, I maintained that concepts, analytical apparatus, and policy-implications which had been erected on those apparently discarded tenets, were surviving in the form of a new neo-Keynesian orthodoxy.

I had expected reasoned objections to my rigorously-stated argument following the publication of my book. None has been forthcoming. Nor has a subsequent article of mine (entitled Keynesian Revisions) which submitted further evidence of a retreat by major exponents of the Keynesian gospel, called forth any reply. In the meantime the retreat has continued

Edition: current; Page: [14]

although, apart from Leijonhufvud's impressive and scholarly critique, I am aware of no further direct attack on the Keynesian system.

The purpose of the present article is not to present additional criticisms of Keynesian economics or of the actual content of the neo-Keynesian orthodoxy which has emerged. My aim is to throw light on some of the causes which appear originally to have created, and since to have been perpetuating, the hold that neo-Keynesianism has acquired in academic circles. I shall refer also to the prospects of early or ultimate emancipation from the consequences of the Keynesian episode.

The reasons for the extraordinary seductiveness of the notions which Keynes' disciples gradually systematized into “Keynesianism” and later rehabilitated into “neo-Keynesianism,” concern the psychology of opinion-the genesis of intellectual fashions, creeds and ideologies. The broad topic is one which began to interest me as a young man, very soon after I had entered academic life. In 1936, I recorded the results of my early endeavors to clarify my thoughts on the subject in my Economists and the Public, a Study in Competition and Opinion. While that book was in the press, The General Theory was published. I read quickly through such parts of Keynes' book as I could then follow, and I managed to insert an additional, last-minute passage in my own book, which recorded my rapidly gained impressions. Already, in 1936, although I had been bewildered by it, I had seen clearly, and predicted, that The General Theory would have a quite unparalleled influence by reason of what I judged to be its demerits as a contribution to thought. For its policy implications appeared to have been chosen for their political attractiveness; its misrepresentations of the “classical” economists seemed certain to have a powerful appeal (because the teachings of the “dismal science” had at all times been accepted with reluctance by those who were unable to refute them); and its obscurities (which I have since come to recognize as due, in every case, to defective thinking), expressed as they were in the language of science, appeared likely

Edition: current; Page: [15]

to enhance its reputation (for all too many people in all spheres-the academic sphere not excluded-are apt to accept obscurity for profundity).

I shall never forget the extraordinary impression left on my mind by the brilliant preface of The General Theory. Keynes' previous writings had struck me as forceful and challenging but rather superficial. I had spent more time struggling with the Treatise on Money than I had devoted to any previous book. Yet, I felt that, in spite of a masterly discussion of index numbers and many beautifully phrased passages, it was a badly-planned, rambling and (I came to fear) an emphemeral work. Some of Keynes' works, such as The End of Laissez-Faire, had impressed me as shallow to the point of irresponsibility. Yet I could not escape the persuasiveness of that preface to The General Theory. It seemed to be announcing a critical, revolutionary contribution of great intellectual courage. I started reading, I remember, prepared for an exhilarating challenge. As I read, my attitude changed quickly to bewilderment and dismay. I had immediately foreseen that, in spite of the obscurity and the apparent muddle of the book, it would have an unprecedented impact; and I was moved to write the prophetic passage to which I have just referred.

Austin Robinson explains how the Keynesian revolution “consisted in inducing a reluctant body of dedicated but perhaps rather cautious, critical, and conservative thinkers to abandon a large part of what they had given their lives to learning and

Edition: current; Page: [16]

teaching, and to accept, as one complete (or virtually complete) package, a set of new and highly debatable propositions and of new ways of handling familiar problems.”

I am only too conscious of the fact that, through the arguments I presented in previous contributions, I also was attempting to induce equally dedicated scholars to turn back and relinquish intellectual capital into which years of study and lecture preparation had been invested. In my case such a task seemed herculean-almost quixotic; for whereas Keynes (who had confidently-almost boastfully-forecast his success in a letter to G. B. Shaw shortly before The General Theory had appeared) was well aware of how popular the policy-implications of his teachings would be, I was just as well aware of how unpopular mine were likely to be-at least for many years to come. Austin Robinson confesses that he finds it difficult to explain how Keynes managed to bring about the revolution. But although I had forecast the unprecedented influence of that book, I find myself unconfident when I try to explain to my own satisfaction the almost irresistible pressures to academic conformity which built up after 1936. Austin Robinson was, I believe, more right than he fully realized when, in his obituary article on Keynes, he compared to “the atmosphere of the revivalist meeting.... “the accelerating conversion of economists to the Keynesian creed. It was, he wrote, “a most illuminating example of the process and psychology of conversion ... not only in Cambridge or in England but all over the world....”

In some measure this almost fantastic phenomenon probably stemmed from the personal attributes of Keynes himself. Harrod and Robinson have convincingly portrayed him as a grand person-gentle, generous, gay, a bon viveur, witty, magnetic, venturesome, scholarly and-among his friends-loyal, kindly, and modest. He was also ambitious, impatient for influence, acquisitive (from a longing for elegant living and those noble things to which wealth gives access), ruthless and casuistic. These are dangerous qualities in an economist, especially in one who, by reason of background, personal charm and knowledge of the world, moved in influential circles.

Edition: current; Page: [17]

I have come to think of him as a strange combination of philosopher, economist, and adventurer. One can discern in his writings as a whole, I believe, a concern with what may be termed “intellectual tactics,” almost reminding one of his success as a gambler and poker player. In his campaign among economists and in his public life he was watching and calculating reactions and devising his career strategy accordingly.

As a thinker, he was original, scintillating and facile rather than profound or dedicated. His temperament and his burning urge to change the course of events militated against profundity. He skated brilliantly and dangerously on the surface, failing to plumb the depths. Of exceptional intellect, yet essentially a man of action, he was capable of mastering rapidly those arguments and teachings which did not clash with his settled convictions. But he treated economists who differed from him radically almost with contempt. He read their contributions hastily-if at all-and with little effort at sympathetic understanding. In his eagerness to bend policy in the direction he favored, he seems to have hidden from himself his failure really to understand what he called “classical” teaching. To refute that teaching he was led to dialectical tricks, recklessly imputing to the “classical” writers opinions which they could never be shown, by actual quotation, to have held. His references to the teachings of the “classical” or

Edition: current; Page: [18]

“orthodox” economists in his tract, The End of Laissez-Faire, and in the General Theory, are almost invariably flagrant misrepresentations. The propensity to attribute to a school of thought one is attacking opinions which any member of that school would indignantly deny is hardly a quality of the detached scholar. Yet Keynes seems to have delighted in a challenging perverseness. He seemed to revel in destroying respect for the patient achievement of sustained intellectual travail by those he felt, more or less intuitively, were somehow wrong. No man could have done more to weaken the authority of his eminent contemporaries and predecessors-to leave an impression that he was debunking them.

Supremely confident, conscious of his reputation and rhetorical skill, he appears to have been self-critical only when his previous speculations had tended to lead him away from instead of towards conclusions to which he was intuitively attached. When he discarded concepts and apparatus which he had earlier introduced, it was because he had found more convincing ways, although sometimes quite different and inconsistent ways, of stating a case which, in its essence, he had not modified. Austin Robinson thinks of him as “remarkably consistent in his strategic objectives, but extraordinarily fertile in tactical proposals for achieving them.” I should say rather that while his convictions about policy seem indeed to have been unshakeable, he constantly changed the arguments, assumptions, terminology and formulae which could be used to justify those convictions. In other words, his fundamental ideas were subject to change only in respect of the particular concepts, formulae or jargon in which he dressed them.

Keynes' biographer, Harrod, says that one gets the feeling, from earlier works, that “he was tentatively and no doubt hurriedly searching for arguments to support a conviction, which was itself more solidly based than the supports which he outlined. It was in fact what we have come to call a ‘hunch.’” I share this feeling that Keynes was “searching for arguments to support a conviction.” But I have it about the whole body of his economic writings. His “hunch” throughout was that

Edition: current; Page: [19]

control of expenditure, via monetary and fiscal policy, could solve the problems of maladjustment expressed in unemployment. And he seems originally to have believed that this could be done without the disastrous sociological consequences of a gradual depreciation of the currency. His intellectual speculations consisted, I think, of a groping around-with great ingenuity-for ways of thinking which appeared to support his “hunch,” selecting and eagerly clutching those which appeared to do so, and inhibiting those which did not. The process was unconscious. I do not impugn his honesty as a scholar.

Harrod tells us also that Keynes “had completed the outline of the public policy which has since been specifically associated with his name” as early as 1924, and that he put forward his proposals then, “before being in a position to give a full theoretical justification of them.” This was, continues Harrod, no doubt “because he deemed it urgently needful for Britain to act with speed. It must not be inferred”.... that his recommendations.... “were thrown out at random.... Did he in some primitive sense already know the theoretical conclusions that he was later to articulate?.... Is it possible for the mind to jump from the data which are the premises of an argument to the practical conclusions, without being conscious oneself of the theoretical conclusions, which are none the less the logical link between the premises and the practical conclusions?” Is not the answer that Keynes' “primitive sense” worked to frustrate, not to promote constructive thinking?

For instance, the desirability of stimulating and controlling internal investment, with public works and limitations on foreign investment, etc., formed an important part of his contribution to the influential 1928 “Liberal Yellow Book.” Even in the midst of 1928 (which some would regard as a boom year in Britain), he was continuously advocating capital expenditure on public account (to rectify the chronic unemployment which, under the paradoxical situation created, had persisted in spite of phenomena which suggested prosperity). As early as 1924, he had advocated a public works policy, and in 1928, when Lloyd George and his advisors thought that public works would be a good plank for the coming election, he gave them his full influential support.

Edition: current; Page: [20]

Again, his Treatise on Money (1930) was an attempt to find methods of eliminating cyclical fluctuations under conditions of price stability. It was an essay in intended refutation of the “classical” view that, for the prevention of depression under currency convertibility, it is essential to prevent the boom. In the General Theory, however, he quietly abandoned any suggestion that his proposals were consistent with long-run price stability, which could be broadly assumed in the Treatise. In doing so, he misdirected attention from all the issues which arise when monetary or fiscal steps taken in the interests of stability of employment have to be limited by the necessity to honor convertibility obligations.

The word “genius” has often been applied to Keynes. But his genius was compounded, I judge, of forensic and diplomatic powers, rhetoric, wit, close range logic, flair for publicity, vitality and charm of manner. He virtually hypnotized most economists who came into close contact with him. In conversation the critical abilities of those who had dealings with him seem often to have evaporated. He could move people by talk where he could never have moved them by the printed word. He won the devotion, indeed idolatry, of his disciples. When I think of the extraordinary effect he had upon some who were once my intellectual friends, I am inclined to feel that I also should have succumbed had I known him personally.

And he was a master of prose. When he was thinking clearly no writer could express himself more aptly, more lucidly, or more gracefully. He was capable of expressing great nobility of ideas, often with almost poetic eloquence. But in his theoretical analyses, in the prose passages which link together his passages of mechanical or mathematical exposition, there is much obscurity; and in Keynes' case, verbal obscurity nearly always meant intellectual confusion. The passages in the Treatise on Money and the General Theory which caused so many headaches to his readers are just those passages in which, I have maintained, his thinking went seriously astray-cryptic sentences or paragraphs which cannot be explained but only explained away. In the intervening passages, in which his hypotheses are largely conclusions invalidly

Edition: current; Page: [21]

reached, his exposition is as easy to follow as anything which has ever been written in economics.

Even those who regard The General Theory as a work of genius sometimes agree (Samuelson's words) that it “is a badly-written book, poorly organized.... arrogant, bad-tempered, polemical.... It abounds in mares' nests and confusions.”

“Arrogant,” “bad-tempered,” “polemical”-these words do not overstate the tone of Keynes' attack on economists whose authority he wished to destroy. To “blast the classical foundations” (as T. Wilson, once put it), he set up (in the words of F. H. Knight) “the sort of caricatures which are typically set up as straw men for purpose of attack in controversial writing,” his writing at times being “more like the language of the soap box reformer than an economist writing for economists.” And his methods of ridicule and misrepresentation have at times been borrowed by his followers. Moreover, the neo-Keynesians are certainly following his example in constantly changing the grounds on which they support given policy-implications.

During the decade following the General Theory, most of the conventional economists who discussed this work seemed to suspend their normal critical approach-almost as though they were afraid of its author. It had been known for some years that his magnum opus was on its way, and I am certain that no work on economics was ever so rapidly or eagerly purchased on its publication. Having obtained the book, economists generally endeavored patiently to find every possible new insight, every new concept, or every new and workable apparatus in his contribution. This was in spite of its distressing obscurities, its slovenly plan, its apparent resuscitation of long discarded fallacies and the indignation it aroused by its misrepresentations. If Keynes' readers could

Edition: current; Page: [22]

find any point of detail on which favourable comment was possible, they usually went out of their way to praise it. Even his strongest critics tended on occasion to give him unmerited credit for novelty.

Harrod refers to a “rabble of detractors” of Keynes and contends that they have falsely accused him of inconsistency. I wish Harrod had named the rabble. Those economists who had the intellectual courage to resist the strong pressures to conformity have never, I believe, been accused of having misrepresented Keynes' arguments when they have tried to show that they are untenable. And I do not think that any economist of the old school would ever have disparaged another for changes of intellectual conviction. The only kinds of inconsistency with which I can recall Keynes having been explicitly charged, are those which concern (a) definitions, and (b) changes in argument to support unchanged conclusions which disciples like Robinson and Harrod himself, have admitted (see above, pp. [Editor: illegible words]..

And other Keynesians have referred, also in emotive language, and without mentioning names, to those who have dared to criticize their leader. E.g., Seymour Harris suggested about twenty years ago that the reaction against Keynesianism then discernible consisted of “unfriendly interpretations and destructive criticisms.” He wrote of “Keynes' baiters.” I am about to examine this change. But surely, if the term “baiter” can be appropriately used of any economist it must be applied to Keynes himself. Austin Robinson describes him as “the great iconoclast.” And Harrod also, refers to “a streak of iconoclasm. To tease, to flout, finally perhaps to overthrow, venerable authorities-that was a sport

Edition: current; Page: [23]

which had great appeal for him.” Harrod excuses Keynes' “barbed utterances,” his “mischievous pleasure.... in criticizing revered names,” on the grounds that “this was done of set purpose. It was his deliberate reaction to the frustrations he had felt, and was still feeling, as the result of the persistent tendency to ignore what was novel in his contribution. He felt that he would get nowhere if he did not raise the dust....”

But were Keynes' “novelties” ignored? Even before The General Theory no economist at any time had ever had his contributions examined with greater care and sympathy, and a more obvious desire to find acceptable developments in them. After a survey of the general tone of the critical literature, I am very doubtful whether Seymour Harris' charge of “unfriendly” interpretations and “destructive” criticisms can be substantiated. At any rate, the only criticisms which made any impression on my own thinking stand in the sharpest contrast to Keynes' own references to the “classical” school, in that they were sober, lenient, tactful and respectful analyses. Keynes' critics never hit back with his own weapons. On the contrary, they apparently strove to give every possible grain of credit to his viewpoint and that of his followers. If the exposure of error is to be regarded as “unfriendly” or “destructive,” academic discussion can hardly proceed.

Edition: current; Page: [24]

On the other hand, Keynes' disciples loaded him with almost idolatrous praise. They excused the slipshod exposition of the book which is supposed to have revolutionized economic science on such dubious grounds as: “His instinct was ... to get his present thinking into the hands of readers before the policies that he was seeking to influence were crystallized. He was a phamphleteer rather than a procrastinating pedant.” And they explained away his extravagances with a tolerance which would never have been extended to a writer with a lesser reputation. We were told that his misrepresentation and ridiculing of orthodoxy-described by Tarshis as emphasizing “his break from the earlier doctrines, ... must be regarded as a tactic of persuasion rather than as an objective statement of the relation between his own work and conventional doctrine.” The offensive parts of his work are described as its “satiric aspect,” an aspect which enhances the “entertainment value” of the General Theory,—his “showmanship,” mere “sport” on his part, his deliberate attempt to “raise the dust.” We are asked not to reject his “theory” because we are forced to reject his “personal opinions,” i.e., his obiter dicta.

There was no need for Harrod to apologize for Keynes' “criticism” of revered names, or even for the “mischievous pleasure” it afforded him, had it merely been criticism. But Keynes'“deliberate reaction,” his ridiculing of disinterested scholars in order to “raise the dust” was his method of dealing with those whose writings he felt instinctively (rather than by force of reason backed by careful study) were untenable. Harrod tells us how Keynes could make the most reckless,

Edition: current; Page: [25]

preposterous and unjust assertions. Yet he is almost naive in his excuses. He describes Keynes' impetuosity and his tendency to speak beyond his book as “minor failings.” They are major failings in a person on whose responsibility and insight the intelligentsia are prepared to place the greatest reliance. Harrod says that Keynes, in the latter part of The General Theory, “may have allowed himself to be carried too far by the exhilaration due to emancipation from old fetters.” That Keynes was exhilarated is understandable. He had found arguments to support policies which he knew were bound to be extraordinarily popular and influential, and his small trusted group of brilliant young advisors had been unable to see serious flaws or unable to convince him of the flaws. No wonder he was exhilarated! But Keynes' attempt to “shake up” the economists, somehow led a whole generation of students of economics to despise rather than examine the great tradition which constituted “classical” economic science (as Keynes used the word “classical”).

In his editorial introduction to a recent evaluation published about six years ago (by nine leading economists) of Keynes' General Theory, Robert Lekachman remarks quite casually, “everybody is a Keynesian now.” Well, the Keynesians have been claiming this, from time to time, ever since it began to be obvious that the very roots of Keynes' teachings were being

Edition: current; Page: [26]

cogently challenged, and in spite of the clearly observable retreat to which I referred at the outset. Lekachman should have added the words, “although they are no longer prepared or able to defend Keynes' revolutionary propositions from devastating criticisms.” For since 1946, Keynes' followers appear to have been spasmodically relinquishing reliance on the theoretical structure of The General Theory while mostly clinging to its terminology, to its form and to its policy-implications.

To some extent the theoretical retreat has been forced by the expression of spontaneous philosophic scepticism from within what has appeared to be the Keynesian camp. In part it has been induced by the need to answer obviously non-Keynesian objections. But in my judgement the main pressure has come through the march of events as they have seemed to contradict the Keynesian thesis. The convictions of the “classical” economists in the 1920's and early 1930's that recourse to the “cheap money” that Keynes had been advocating as a means of restoring activity was a reform in the wrong direction-their warnings that it would lead to the gradual depreciation of the measuring rod of value, the emergence of a proliferation of centrally imposed controls, and the magnification of State power-although fiercely denied at first by Keynes' disciples, have been justified subsequently in every detail.

For instance, in October, 1933, Roosevelt inaugurated a monetary policy which can be said to have embodied the policy recommendations of Keynes' Treatise, which had appeared three years previously. The aim, declared Roosevelt, was to “maintain a dollar which will not change its purchasing power during

Edition: current; Page: [27]

the succeeding generation.” And events continue to mock at Keynesian teachings. During 1958 cheap money and rapidly rising prices in the United States were accompanied by worsening unemployment. Thereafter, almost uninhibited reliance on every conceivable form of Keynesian apparatus, brought no success in eliminating the chronic unemployment of more than five and a half per cent of the labor force until the more rapid inflation inaugurated in 1965 and subsequently maintained. Unemployment in the U.S. had then been maintained at above this figure for nearly seven years. Yet, commented P. W. McCracken in 1964, “one can find no period in the so-called ‘boom-bust’ days, before we exercised our business-cycle taming talents, when unemployment was this high for such a long span.” Under Keynesian experience, “the tolerable level” of unemployment has indeed (in Lekachman's words) shown “a secular tendency to rise.”

Edition: current; Page: [28]

The failure seems to have been abject; and without a more rapid drift towards totalitarian government, it is unlikely, I suggest, that Keynesian policy will again achieve the appearance of success in the western world; for it will be necessary for government to suppress reactions to the expectation of inflation over an ever-expanding area of the economy. The suppression of such reactions ought by this time to have been clearly recognised as the ultimate raison d'être of each Keynesian “persuasion” or “control.” Let the reader ask himself whether every “success” achieved by cheap money in the past has not been due to the mass of people not expecting it, or not expecting its duration or the speed with which it has occurred; or being prevented, by authority, from behaving rationally in the light of their predictions.

It may well be that if Keynes had never lived, contemporary history-of thought and action-would hardly have differed. If he had not provided a supposed justification for the various media through which inflation can be engineered, with the whole range of “central controls” needed to make the chronic, creeping, crawling rise of prices politically acceptable, some other prophet could conceivably have provided supposedly scientific authority, with a different jargon and formulae. To retain office, governments had to compete with policies which were both plausible and not unacceptable to the more powerful pressure groups, such as labor and organized agriculture. Keynesianism has proved to be a stratagem which enabled governments to do this without early disaster. “A great change in outlook was required ...,” says T. Wilson. It was Keynes' “rhetoric and new mystique which carried the day.”

So severely have Keynes' doctrines been treated, however, that some economists, although seemingly reluctant to renounce the Keynesian approach, have nevertheless been suggesting during the last decade that all these controversies belong to the past. We are now “well into the post Keynesian era,” they are apt to say. Yet others (speaking rather from the non-Keynesian camp) sometimes declare that “we are all

Edition: current; Page: [29]

Keynesians now.” The truth is, I think, that most economists feel themselves forced to talk and teach in what has become the modern economic language in order to retain respect and get a hearing, in spite of the unsatisfactory concepts and misleading terminology to which they are, I have tried to show, thereby committed. Through a powerful urge to follow well-worn trails in post-war academic discussion, economists have found themselves trapped in a dense Keynesian undergrowth. They mostly realize now that they have for too long followed a leader who was himself lost; but many appear to be resigned to their fate-unwilling to make the effort of hacking their way out of the conceptual jungle in which they are entangled.

The aversion to confessions of past error is understandable enough, especially when the first to confess may suffer in status and prospects. But some perhaps tell themselves that after all, however fallacious Keynesian theory may be, the policies it implies are, for political reasons, wiser than “classical” policies. Even so, if that is an economist's conviction, it is still his duty to explain why “classical” remedies must be held to be defective from the angle of political acceptability.

We can consider the position of H. G. Johnson, who, like so many former Keynesians, appears to admit that the vital originality of the General Theory-the unemployment equilibrium thesis-is untenable. He does not argue that Keynes' economics is defensible but that his “polemical instinct was surely right....”; for, says Johnson, “neo-classical ways of thinking were then” (i.e., in 1936) “a major obstacle to sensible anti-depression policy.” In other words (I hope this interpretation is not unfair), in spite of the fundamental fallacy on which, he agrees, Keynes' thought was based, it did serve a beneficial purpose; for the authority of “classical” anti-depression thought, which Johnson holds had not been “sensible,” was dealt a deadly and necessary blow.

Edition: current; Page: [30]

But exactly how can it be held that the policy implications of “classical” thought were not “sensible?” After all, they were never put to the test. Does Johnson perhaps mean that, although “classical” remedies could undoubtedly have restored prosperity in the thirties, it was hopeless to expect an electorate (and hence politicians) either to understand or to adopt those remedies? Certainly economists who regard pre-Keynesian teachings as not being “sensible,” may be thinking simply of the admitted difficulty or the supposed impossibility of winning political consent for the reforms to which those teachings were pointing. That being so, they may believe Keynes' polemics to have helped persuade the community to be “sensible,” in the sense (i) of acquiescing in inflation whenever unemployment or recession is threatening, as a crude means of confiscating the real gains from money wage-rates forced above the full employment value, or (ii) of acquiescing in authoritarian “incomes policies,” “controls,” “ceilings,” “persuasions” and “guide-lines” intended to curb the traditional tendency of labor unions to reduce the flow of uninflated wages, so as to render inflationary co-ordination less essential. If that is the case, the neo-Keynesians should make it clear beyond doubt.

It is possible, however, that “classical” remedies are held not to have been “sensible” because of some radical weakness (which Keynes himself did not discern) in the abstract reasoning which inspired them. That is a quite different point. Pre-Keynesian anti-depression teachings are to the effect that unemployment (as a short-term phenomenon) and depression are due to a contraction of the flow of wages and other income through some disco-ordination of the pricing system. The most important case of this disco-ordination is thought to be caused by wage-rates (and hence final prices) being fixed too high in relation to income or inconsistently with price expectations. Labor unions and, in some countries, a form of subsidized unemployment “insurance,” are usually diagnosed as the major factors which encourage the pricing of the flow of productive services inconsistently with full or optimal use of men and other resources. More generally, “classical” thought implies that the avoidance of depression is to be most wisely achieved through (a) the avoidance of inflation which, under any system in which the money unit has

Edition: current; Page: [31]

some defined value (or some politically expedient value), will have to be corrected by deflationary rectifying action and (given rigidities in the wage and price system) a decline in activity; and (b) the deliberate planning of institutions conducive to market-selected price and wage-rate adjustments in response to economic change, in order to maintain or enhance the flow of uninflated wages and income. But once the persistent ignoring of “classical” precepts has precipitated chaos, and insurmountable political obstacles obviously block the way to non-inflationary recovery, only a pedant would oppose inflation.

Now there may be one or more serious flaws in the theory which I have so briefly stated. If so, I know of no serious exposition which sets out to indicate the flaws, apart from the Keynesian unemployment equilibrium thesis, which appears now to have been discarded. Yet the neo-Keynesians seem prepared neither to provide new (non-Keynesian) criticisms of the “classical” case nor overtly to return to it.

The chief tragedy of what, I believe, will ultimately come to be regarded as the Keynesian episode in the history of academic economics, is that it has hindered the development or refinement of theory during an epoch in which institutional changes have been demanding a sharpening of the tools of analysis. What seems to have been happening since 1936 is that “fundamental economics” (which had been concerned with the devising of tools for studying the causes of observable economic phenomena) has been branching-not improperly-into “operational economics,” that is, towards formulations of economic analysis suitable for application in already-adopted governmental economic policy, making abstraction of the rationality of that policy. But the emergence of “operational economics” has degenerated all too easily-via Keynesian

Edition: current; Page: [32]

influences-into “economic apologetics.” By that, I mean the devising of concepts and theoretical constructions which can be used to justify policies which have the virtue (or the reverse) of being politically acceptable. Future historians of economic thought will, I predict, give Keynes chief responsibility for having inaugurated-I do not suggest intentionally-the flood of economic apologetics in which neo-Keynesian economics has become submerged.

I should be the last to decry the development of the State's sphere in the acquisition and interpretation of the data relevant to the guidance of its own co-ordinative activities and those of private entrepreneurs. This is the valid role of “operational economics.” Much of the effort expended in the collection of the information utilized in national accounting is of value not only to the administrators of the credit system (especially if they are contractually bound to maintain a money unit of some defined value), but to all decision-makers in whose calculations the future money valuation of income is important.

The fulfillment of this task requires a supply of economist-technicians, and not unnaturally the faculties of economics of the major universities of the western world have been under pressure to become schools for the training of such “economists” or “economist-statisticians.” But are the students who receive this training being taught to perceive clearly the co-ordinative role of the pricing system? Or are they being indoctrinated with the view that it is their task to help use the data collected to correct, through the “control of expenditure,” an inherent tendency to equilibrium with unemployment in a free market system, or to offset discoordinations caused through the pricing of labor (or other sources of output) having been exempted from the sanctions of social (i.e., market) discipline?

Edition: current; Page: [33]

The defensible scope of central direction and leadership (“indicative planning”) in a free market economy cannot be perceived, nor can the techniques employed be made fruitful, as long as Keynesian notions are allowed to cloud the issues. But it seems to me that today, in almost all the universities everywhere, we find the inculcation and perpetuation of the Keynesian approach, together with the exclusion of competing ideas.

I attempted to arouse interest in this situation in 1964. I wrote: “It was about 25 to 30 years ago that most of the younger sceptics who expressed misgivings about the ‘new economics’ began to be eliminated from academic life. There was no inquisition, no discernible or intentional suspension of academic freedom; but young non-conformists could seldom expect promotion. They appeared rather like young physicists who were arrogant enough to challenge the basic validity of revolutionary developments which they did not properly understand. To suggest that Keynes was all wrong was like questioning the soundness of Einstein or Bohr. The older economists could declare their doubts without serious loss of prestige, but any dissatisfaction on the part of the younger men seemed to be evidence of intellectual limitations.”

The position today is that a relatively small group of economists, scattered through the universities, adhere pertinaciously-not dogmatically-to the time-honoured traditions of “classical” economics. But even they tend mostly to use Keynesian terminology to the detriment (I believe) of their own and their students' thinking. Moreover, the majority of the teachers of economics of the contemporary generation seem never really to have learned, or to have forgotten, what the pre-1930 economists were explaining. For the younger economists now to question the currently fashionable approach demands not only a rare insight but intellectual courage, and I have an uneasy feeling that, for those of junior status, it may demand also a willingness to sacrifice professional prospects in the interests of scientific integrity. I do not

Edition: current; Page: [34]

of course imply that there are no outlets for the expression of dissenting thought. But there is no longer, I believe, anything resembling equality of opportunity in the communication of ideas in academic circles generally.

The economists of the great universities ought, I suggest, to be asking themselves whether, in their field, academic freedom is really being effectively preserved. Are they certain, for instance, that junior staff who might feel some sympathy with ideas such as I have expressed in my book on Keynesianism or even with Leijonhufvud's analysis (which is less iconoclastic than mine) could openly confess to that sympathy without damaging their academic prospects? In some cases they might well answer affirmatively. There are a few universities in which such confidence would be fully justified. But discussions with economists who share my fears convince me that, in Britain and the United States at any rate, the set-up is seldom conducive to the expression of unorthodox (i.e., non-Keynesian) ideas. Even senior economists have confessed to me that they are subject to powerful pressures to conform to fashion. Some say that they feel under an obligation to train their most promising students along lines which are likely to make them acceptable as teachers in other universities, or as public servants in administrations dominated by Keynesian convictions. Others feel that any existing consensus of opinion carries its own authority. A young British economist with whom I was discussing some of my ideas a few years ago made no attempt to answer any of the points I was making. He simply asked, “How many economists would agree with you today?” Others still are intimidated by the power-holding establishment. In 1964, I asked a distinguished middle-aged American economist who seemed to appreciate my misgivings on many issues, whether he would not express his views in writing. He answered, “I dare not. I should probably be black-listed.” And about the same time I asked a brilliant youngish economist in Britain, who, I had good reason to believe, would have been inclined to accept the heresies I have been propounding, why he did not himself openly challenge the Keynesians. He replied, “I am scared. They are much too powerful.”

Furthermore, the editors of the more important journals are, on the whole, pillars of the dominant orthodoxy. It is understandable that they should tend to reject contributions which directly challenge the currently fashionable analysis. Young economists have confessed to me that they have felt it essential, in submitting contributions to certain leading journals, carefully to exclude or rewrite passages which might

Edition: current; Page: [35]

suggest non-conformity. There are reasonable grounds for uneasiness here. But it is in the content of undergraduate and graduate teaching that the widespread exclusion of competing modes of thought appears to me to be having the most grave consequences.

The modern emphasis on macro-economics, the validity of which depends—as few writers in the field seem to realize—upon its reconciliation with micro-economics, aggravates the situation. For macro-economics, which is particularly amenable to mathematical enunciation, is now being taught at an early stage in the typical curriculum; and the young student tends, I fear, to spend more time grappling with mathematics than with economics, the difficulties of which are not mathematical. His attention is diverted from rigorous thought about the phenomena of scarcity and price, and the stabilizing and co-ordinative role of the price system, to the study of complex truisms. When he graduates, he may have learned very little of basic economic science. If he tries to resolve in his mind the apparent conceptual confusions which most macro-economists elaborate, he is likely to prejudice his academic record. Students with a lively and critical intelligence have admitted to me that they have felt it expedient (in the struggle for good symbols) to echo current texts and teachings mechanically, inhibiting all concern with their validity.

Despite my conviction that an economic creed has become entrenched within most of the universities, a Keynesian priesthood determined to retain its hold, I have no doubt that the majority of economists in all the universities are sincerely convinced that the greatest possible opportunity for the free expression of divergent ideas by those whom they regard as competent critics has been preserved. But critiques of Keynesian concepts which have appeared during the last decade do render purposeless an enormous collection of apparatus, constructed through the expenditure of formidable, scholarly effort since 1936. This alone must have created powerful

Edition: current; Page: [36]

motives for resistance to the expression of competing teachings which threaten to precipitate widespread obsolescence in academic capital.

But the genuineness of the ever-present resistance to heresy does not weaken the force of my charge. And are not the dangers to academic freedom to which I have referred magnified when university economists are hoping for influence as advisers of governments? Even if we assume that there is no question of bias due to pecuniary interest, a more elusive problem remains. Governments tend notoriously to disregard economists whose advice they believe it would be politically inexpedient to follow; and in the endeavour to exercise at least some guidance on the course of events, economists may all too easily be led to a compromise which ultimately weakens the force of disinterested and expert teachings.

A barrier to the communication of ideas needs to be broken. This might happen through initiatives from among the economists themselves; through deliberate action on the part of the governing bodies of universities anxious to avoid the slur of indoctrination; or through growing pressure from independent-minded graduate or undergraduate sceptics who recognize and

Edition: current; Page: [37]

resent an indoctrination which has remained too long without potent challenge.

Edition: current; Page: [38]

Ludwig von Mises and the Market Process

L. M. Lachmann

I.

In the thickening gloom of our age, an age of declining standards, rampant inflation, and egalitarian ideology, it is perhaps too much to hope that the realm of economic thought alone will remain unscathed and at least this province of the human mind escape invasion by our contemporary follies. In fact, what we find to-day is very much what one might have expected. We see a few thinkers engaged in a valiant but desperate struggle to defend and strengthen the great tradition they have inherited. The large majority of economists have to-day adopted an arid formalism as their style of thought, an approach which requires them to treat the manifestations of the human mind in household and market as purely formal entities, on par with material resources. Not surprisingly, the adherents of this style of thought have come to find the mathematical language a congenial medium in which to give expression to their thoughts.

They are fond of referring to themselves as “neoclassical” economists. This label is, however, rather misleading. The classical economists, in their great day, were concerned with human action of a certain type, the forms it takes in varying circumstances and the results it is likely to produce. They took the market economy of their time as object of their thought and asked why it was what it was. Gradually they built up a formal apparatus of thought in order to deal with these problems.

The “neoclassical” economists of our time have taken over, developed and considerably

Edition: current; Page: [39]

refined this apparatus of thought. But in doing so they have taken the shadow of the formal apparatus for the substance of the real subject matter. It will not surprise us to learn that when confronted with real problems, such as the permanent inflation of our time, neoclassical economics has nothing to say. “Late classical formalism” appears to us a much better designation of the style of thought currently in fashion in these quarters.

A prominent economist of this school has recently told us, “Until the econometricians have the answer for us, placing reliance upon neoclassical economic theory is a matter of faith.” What a faith! Economics is by no means exclusively concerned with what happens, but also with what might have happened, with the alternatives of choice which presented themselves to the minds of the decision-makers. In fact, it is in terms of these alternatives alone that the decisions can be rendered intelligible, which is after all the main purpose of a social science. Statistics, as Mises has often explained, merely record what happened over a certain period of time. They cannot tell us what might have happened had circumstances been different.

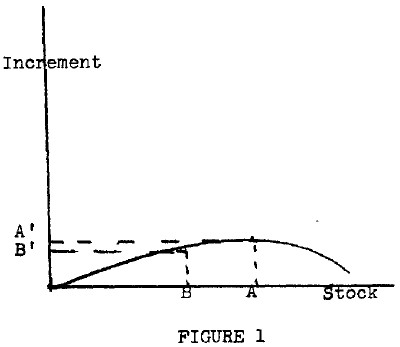

Thirty years ago Mises warned us of the futility of late classical formalism. Characteristically he thrust his blade into his opponents' weakest spot. He showed the inadequacy of the main tool of the formalists, the notion of equilibrium. “They merely mark out an imaginary situation in which the market process would cease to operate. The mathematical economists disregard the whole theoretical elucidation of the market process and evasively amuse themselves with an auxiliary notion employed in its context and devoid of any sense when used outside of this context.” And he added “A superficial analogy is spun out too long, that is all.”

Edition: current; Page: [40]