Edition: current; Page: [i]

reprints of econonmic classics

Volume I

Edition: current; Page: [ii]

Edition: current; Page: [iii]

together with the

OBSERVATIONS UPON

THE BILLS OF MORTALITY

more probably by CAPTAIN JOHN GRAUNT

edited by CHARLES HENRY HULL, Ph.D.

cornell university

VOL. II

Edition: current; Page: [iv]

INDIANA UNIVERSITY LIBRARY

Library of Congress Catalogue Card Number 63-23521

Edition: current; Page: [v]

Edition: current; Page: [vi]

Edition: current; Page: [vii]

PREFACE

The writings of Sir William Petty may be roughly divided into three classes. The first relates to his activities as surveyor of forfeited lands in Ireland under the Protectorate; its present interest is chiefly biographical. The second includes his papers on medicine and on certain mathematical, physical and mechanical subjects. These are now forgotten. The third class comprises his economic and statistical writings. The merit of these has been freely recognized. No writer on the history of political economy who touches the seventeenth century at all has failed to praise them; but the scarcity of the scattered pamphlets in which they were published has prevented them from becoming as generally known as they deserve to be. The present edition of Petty's Economic Writings is designed to meet this difficulty. It has not been undertaken without warrant. Critics as diverse as McCulloch, Roscher and Ingram have noted the need of a collected edition of Petty's economic pamphlets, and it appears that his descendants have twice considered its publication. But the project of the Earl of Kerry was interrupted by his untimely death,

Edition: current; Page: [viii]

and Lord Edmond Fitzmaurice, who had contemplated supplementing his “Life of Petty” by an edition of Petty's works, generously surrendered his intention upon learning that a similar undertaking was already under way.

The editor has endeavoured to include all of Petty's published writings which bear upon economic or statistical subjects. The “Observations upon the Bills of Mortality of London,” though they probably were not written by Petty, are also reprinted—not less on account of their intrinsic merits than because of their close connection with his acknowledged works. The text selected for reproduction is, in each case, that of the best published edition, and the original paging is indicated in the margin. By good fortune authentic manuscripts of several of the works are still preserved, and their readings, given in the foot-notes, make a number of passages clear which, as heretofore printed, were confusing or absurd. One considerable tract, the “Treatise of Ireland,” and a few fragments, are added from manuscripts hitherto unpublished.

The notes are confined, for the most part, to the economic or biographical aspects of the passages commented upon, and no attempt has been made to elucidate purely historical questions. Thus when Petty asserts that in the Irish Court of Claims after the Restoration all claimants were fully heard, the editor does not enter upon a discussion upon that disputed point. In the introductory sections, likewise, he has not used the opportunity to sketch the general history of political economy apropos of Petty and Graunt, but has confined himself to such remarks as are thought to bear directly upon them and their writings. On the other hand

Edition: current; Page: [ix]

the history of the London bills of mortality has been entered into at some length, as no place seemed more appropriate to that purpose than a reprint of the writings which first indicated the importance of the bills.

In preparing this book, the editor has received help from a number of persons, to all of whom he would express his appreciation of their kindnesses. It gives him especial pleasure to acknowledge the gracious permission of the Marquis of Lansdowne to consult the Petty papers at Bowood—though it became impossible for him to make use of that privilege—and to thank Lord Edmond Fitzmaurice for repeated suggestions. He has received valued assistance from J. Eliot Hodgkin, Esq., of Richmond-on-Thames, from the Rev. Dr. William Cunningham of Trinity College, Cambridge, from Professor F. York Powell of Oxford, from Professor V. John of Innsbruck, from his colleagues H. Morse Stephens and Walter F. Willcox of Cornell, and from his sister. None of these however should be held responsible for such errors as may be found in the book.

Various officials of the British Museum, the Record Office, the Royal society, the Bodleian Library, the libraries of Cambridge University and of Brasenose College, Oxford, of the Royal Irish Academy, the King's-Inns, and Trinity College, Dublin, of the Institute of France, the Universities of Leipzig and of Pennsylvania, and of Harvard and Cornell Universities have allowed the editor the use of sundry books and manuscripts. For privileges of this character he is under especial obligation to Professor Michael Foster, Secretary of the Royal Society, and to the Rev. Llewellyn J. M. Bebb, Librarian of Petty's college. He cannot omit to mention,

Edition: current; Page: [x]

likewise, the services of the proof-readers who have made comparisons with manuscripts and original editions to which he has no present access.

Last but by no means least, he wishes to acknowledge both the generosity of the Syndics of the University Press in providing for the publication of a book whose editor might have looked in vain for assistance at home, and the untiring patience of their Secretary, Mr Richard T. Wright, who must have been sorely tried by its slow passage through the press.

Edition: current; Page: [xi]

CONTENTS

- Introduction . . . . . . . .

- Petty's Life . . . . . . .

- Graunt's Life . . . . . .

- The Authorship of the “Observations upon the Bills of Mortality” . . .

- Petty's Letters and Other Manuscripts .

- Petty's Economic Writings . . . .

- Graunt and the Science of Statistics . .

- On the Bills of Mortality . . . .

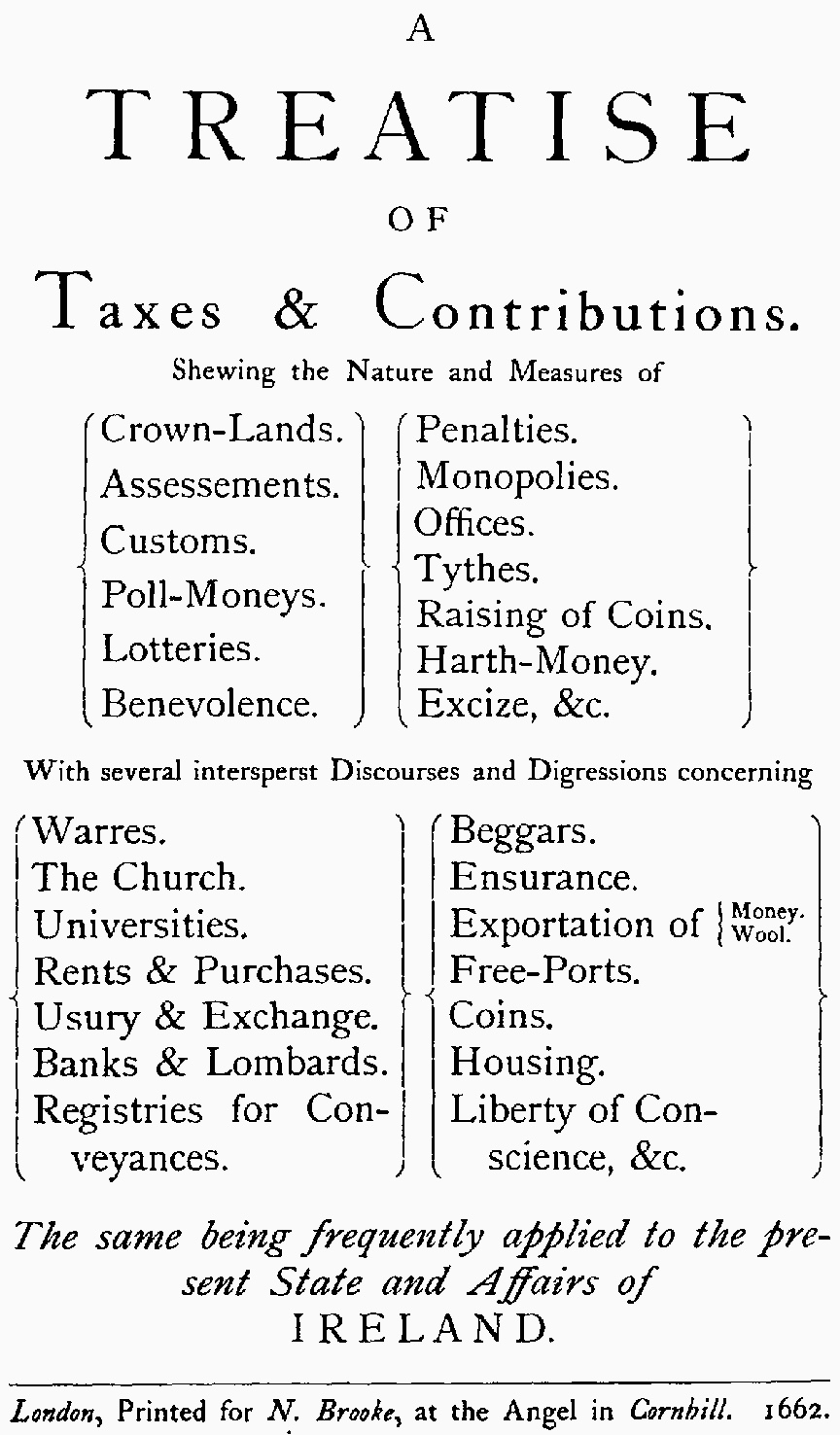

- A Treatise of Taxes and Contributions. London, 1662 . . . . . . . .

- Verbum Sapienti. [1664.] London, 1691 . .

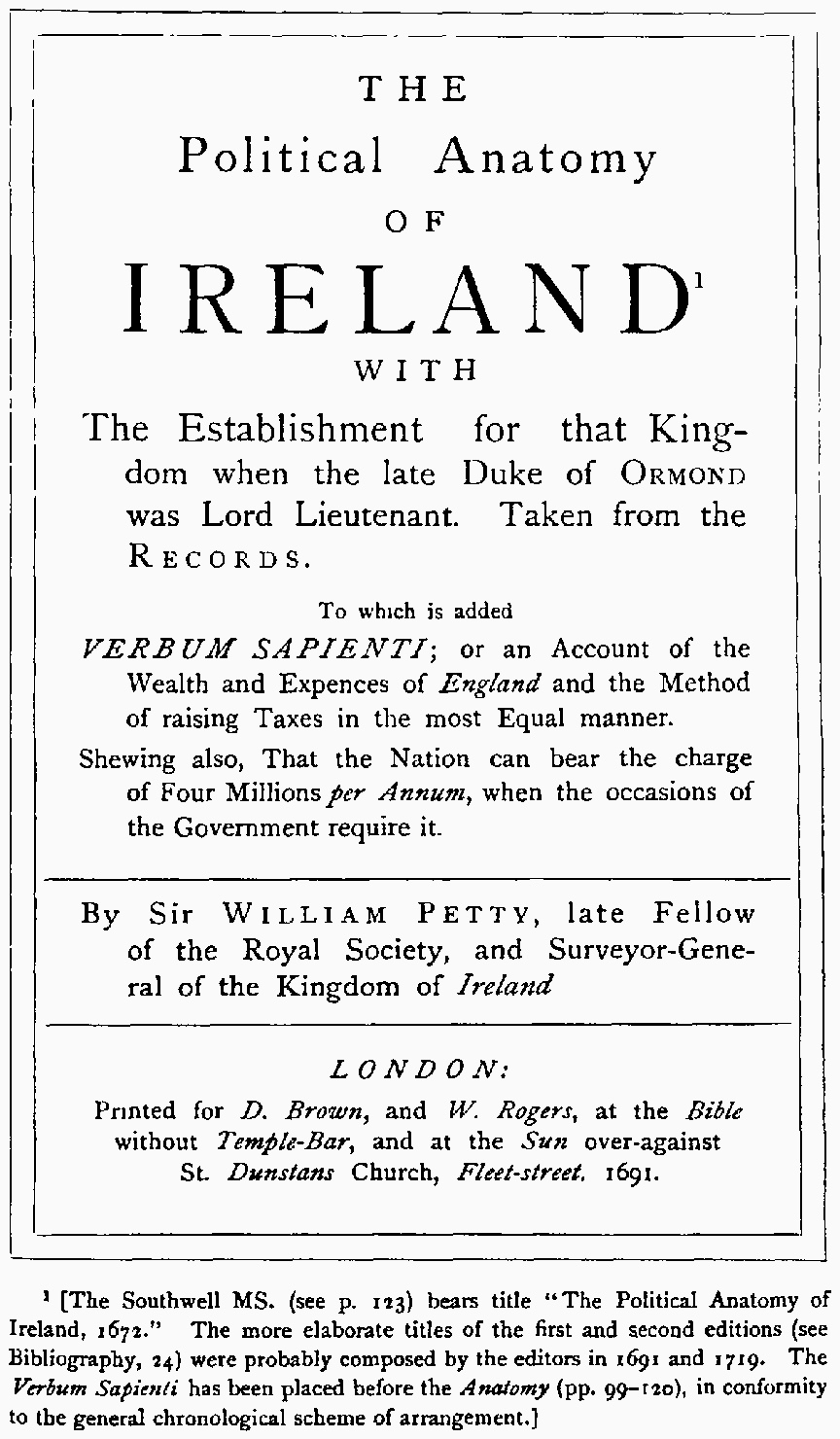

- The Political Anatomy of Ireland. [1672.] London, 1691 . . . . . . . . . .

- Political Arithmetick. [1676] London, 1690 . 233–313

Edition: current; Page: [xii]

Edition: current; Page: [xiii]

INTRODUCTION

PETTY's LIFE.

William Petty was born on Monday, 26 May, 1623, at the house of his father, a poor clothier of Romsey in Hampshire.

According to the detailed account of his childhood which he gave to Aubrey, his chief amusement consisted in “looking on the artificers, e.g. smyths, the watchmaker, carpenters, joiners, etc.” until he “could have worked at any of their trades.” “At twelve years of age he had acquired a competent smattering of Latin,” and before his sixteenth year he was well advanced in Greek, mathematics and navigation. It was, perhaps, in his fourteenth year that Petty

Edition: current; Page: [xiv]

was overtaken by an accident which gave him opportunity to turn his precocity to good account. After some ten months' service as cabin boy on an English merchantman, he had the misfortune to break his leg. Hereupon the crew set him ashore on the French coast, not far from Caen. The unhappy lad, thus left to shift for himself, recounted his misfortunes in Latin so excellent that the Jesuit fathers of that city not only cared for him but straightway admitted him a pupil of their college. Here he prosecuted his former studies and incidentally learned the French language as well. Meanwhile he supported himself in part by teaching navigation to a French officer and English to a gentleman who desired to visit England—Latin serving, apparently, as the medium of communication in both cases—and in part by traffic in “pittiful brass things with cool'd glasse in them instead of diamonds and rubies.” Upon his return to England he appears to have spent some months in the Royal Navy, but in 1643, “when the civil war betwixt the King and Parliament grew hot,” he joined the army of English refugees in the Netherlands and “vigorously followed his studies, especially that of medicine,” at Utrecht, Leyden and Amsterdam. By November, 1645, he had made his way to Paris where he continued his anatomical studies, reading Vesalius with Hobbes and forming many acquaintances in the group of scholars that gathered around Father Mersen and the Marquis of Newcastle. In the following year he returned to Romsey, and appears to have taken up for a time the business formerly carried on by his father. At Romsey he busied himself also with an instrument for double writing, which he had so far completed by March, 1647, that a patent upon it was then granted him for a term of seventeen years. In November, if not earlier, he went to London with the intention of selling this device. His expectations were not realized, and it may be inferred from his subsequent remarks upon patent monopolies that his career as an inventor proved far from gainful. In London Petty was “admitted

Edition: current; Page: [xv]

into several clubbs of the virtuosi,” and secured the friendship, among others, of Milton's friend, Samuel Hartlib, to whom he addressed the “Advice of W. P. for the Advancement of some Particular Parts of Learning.” It was upon Hartlib's encouragement, also, that he began his abortive “History of Trades.”

In 1648 Petty removed from London to Oxford, where the University had been recently reorganized by the parliamentary party. He was soon made deputy to Clayton, the professor of anatomy, and succeeded him in January, 1650, “Dr Clayton resigning his interest” in the professorship “purposely to serve him.” Meanwhile he had become a doctor of medicine and a fellow of Brasenose College, and, in December, 1650, had added to his reputation by participating in the reanimation of one Ann Green, a wench hanged at Oxford for the supposed murder of her child. At about the same time he was chosen vice-principal of Brasenose and professor of music in Gresham College. The vice-principalship he retained until 9 August, 1659, the Gresham professorship until 8 March, 1660. In April, 1651, the visitors to the University had granted him the unusual favour of two years’ leave of absence, with an allowance of £30 per annum. The occasion of this grant and the nature of his occupation during the next few months are unknown; Lord Edmond Fitzmaurice conjectures that he travelled. However that may be, there soon came to him an appointment which exercised a determining influence upon the entire course of his subsequent life;

Edition: current; Page: [xvi]

he was made physician to the army in Ireland and to the family and person of the Lieutenant-General. Thenceforward his chief interests, both material and intellectual, were intimately connected with affairs beyond St George's Channel.

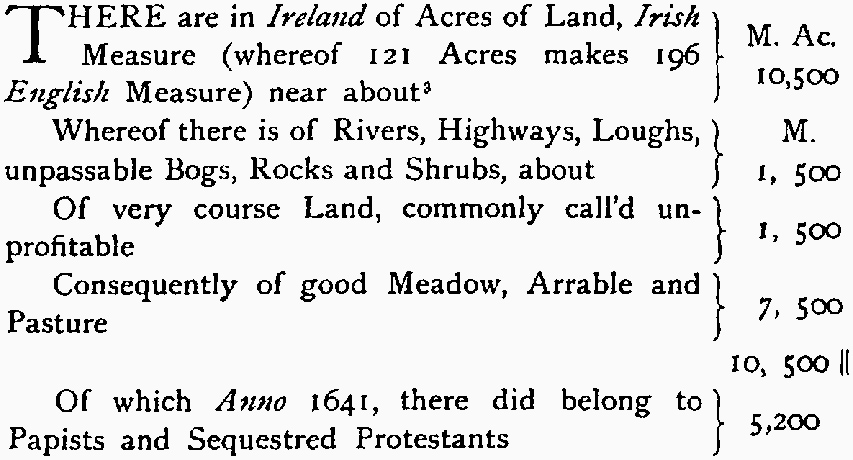

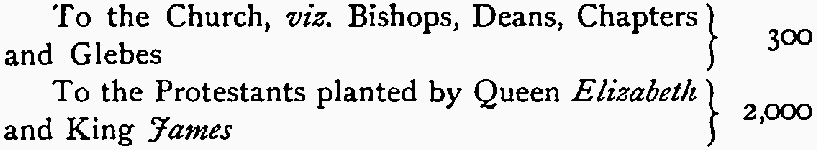

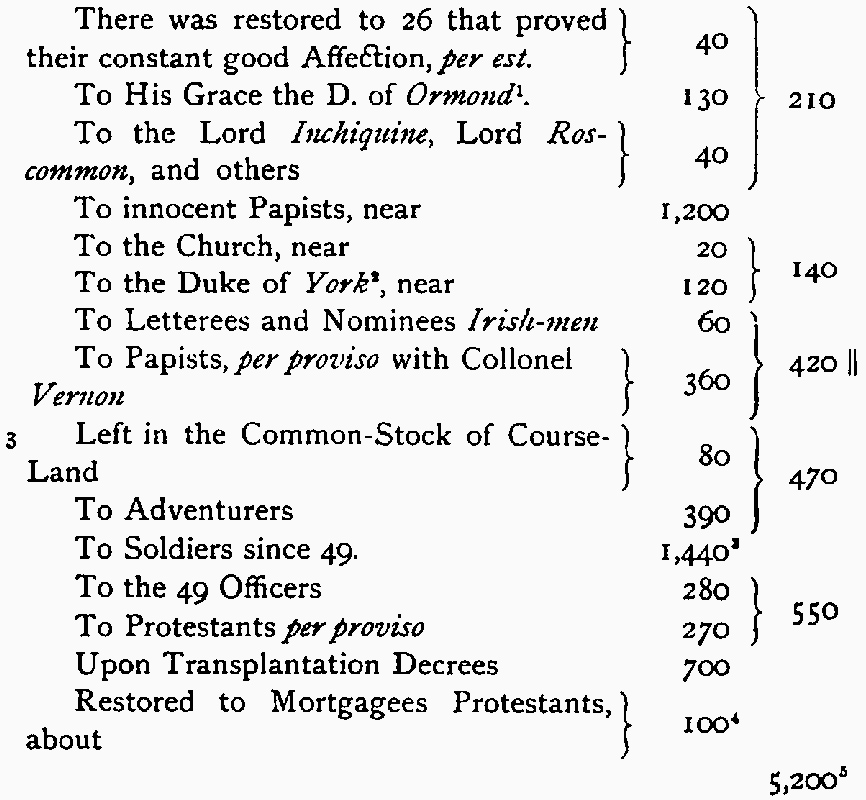

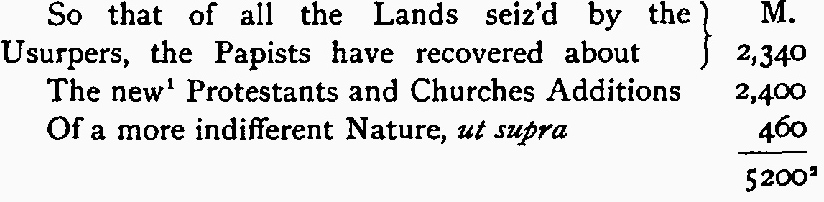

As physician to the army Petty resided in Ireland nearly seven years, returning to England in 1659 as the bearer of Henry Cromwell's letter of acquiescence in the government set up by the Rump. It was during this first period of his Irish residence that he made the “Down Survey” of Ireland, a work which laid the foundation of his fortune and constituted his earliest title to fame. After the suppression of the Irish rebellion of 1641 the government prepared to distribute the forfeited lands of the rebels, one moiety among the soldiers of the victorious army, the other among the adventurers who, under the provisions of 17 Car. I., c. 34, had advanced money for the army's support. As a preliminary to the proposed distribution, it was necessary that the situation and area of the forfeited holdings be determined. When Petty first reached Ireland he found a survey for this purpose already in progress. He soon concluded that this survey was being “most insufficiently and absurdly managed” by its director, one Benjamin Worsley, and he promptly proposed to make a more satisfactory survey himself. This he promised to complete, duly set down in maps

Edition: current; Page: [xvii]

and books, within a year and a month. After much discussion his proposals were accepted, 11 December, 1654, but the time for the completion of the survey was afterwards extended to thirteen months from February, 1655. Petty thus agreed to measure and record, on a scale of forty perches to an inch, all forfeited lands, profitable and unprofitable, set aside for the satisfaction of the officers and soldiers,—the so-called “army lands”—down to the smallest recognized civil denominations. He also undertook to survey and map, for general use and upon a smaller scale, the bounds of all baronies, whether forfeited or not, in all counties which contained forfeited lands. By March, 1656, the survey of the army lands was virtually completed, and he applied to the Council for payment and for release from his bond. His work was referred to a committee representing the army and was by them pronounced satisfactory. Worsley, on the contrary, pointed out a number of minor errors. These were such, in Petty's view, as should “bee not charged uppon” him “as faults” but rather such accidents and disasters as ever attend vast and variable undertakings.” Nevertheless he attempted a detailed answer to Worsley's objections. General Larcom, a judge eminently competent, declares that he met the charges “satisfactorily, indeed triumphantly: for whatever shortcomings or blemishes might be detected in so great a work, performed with such extraordinary rapidity, over so great an extent of country at the same time, there can be no doubt that, on the whole, it exceeded the articles of agreement, and that the delay which will be seen to have taken place in the payment, was vexatious and unjust.” Nevertheless Petty was obliged to wage a prolonged contest for his rights, the final order for his payment being postponed until March, 1657, while his bond was not released until December of the same year. The publication of the results of the general survey, on the other hand, appears to have been delayed for several years.

The completion of the Down Survey of the army lands by no means concluded Petty's “services and sufferings” in Ireland. On the 7th July, 1656, he was named a member of the commission to distribute among the officers and soldiers the forfeited lands which he had surveyed. Vincent Gookin, one of his associates on the commission, presently departed for England to attend Parliament, and fear of offending military friends deterred the other member,

Edition: current; Page: [xviii]

Major Miles Symner, from taking an active part in its labours. Petty was therefore, obliged, “to manage the executive part of that vast and intricate work, as if it were alone, Few other Commissioners (for fear of falling into some Error) adventuring to do business without” him, “Whereby all displeasures real or imaginary, were accounted not onely” his “Permission but Commission: Not onely” his “simple Act, but design, contrivance and revenge.” Working thus single-handed, he set out their lands to the army with such dispatch that the distribution was completed in February, 1657. Meanwhile he had begun, in conjunction with Worsley, a survey of the adventurers’ moiety of the forfeited lands. Distribution based upon this survey was delayed by disagreements among the adventurers at London until finally, in May, 1658, the patience of the Lord Deputy was exhausted by their indecision and he sent Petty to treat with them for the appointment of a commission which should adjust their claims out of hand. Upon his arrival in London, Petty found the adventurers already in receipt of an anonymous communication from Dublin, alleging that he intended if possible to cheat them as, it was charged, he had cheated the army. In the face of this charge he won the entire confidence of the adventurers’ committee, and was provided by them with a petition to the Council at Dublin requesting “that, instead of all the said Commissioners, Dr Petty alone may bee authorized and approved by your Lordshipps, to act as well in behalfe of your Lordshipps as the adventurers, as a person best able to give the business a dispatch.” The news of his triumph at London stirred up Petty's enemies at Dublin to prepare a second letter—Petty called it a libel—directed ostensibly to the adventurers and assuring them that his dishonesty in surveying and setting out the army lands had gone unpunished only because of his position as a clerk of the Council and prime favourite of the Lord Deputy. By prearrangement this letter was intercepted on its way to London and was brought to the attention of Henry Cromwell. Cromwell, whose confidence in Petty never wavered, at once referred the charges to a committee of seven officers. “Whilst these things were doeing in Ireland, the doctor rides night and day from London, in the end of December [1658], and through many hazards comes to

Edition: current; Page: [xix]

Dublyn, God having kept him safe in the greatest storme that ever was knowne, as he thankfully construed it, to preserve him for his vindication.” At Petty's request the officers’ committee already appointed was increased by the addition of “the Receiver-General, Auditors-General, and one Mr Jeoffryes, a person well reputed for his integrity and skill in accompts, that, having given a satisfactory accompt unto these able and proper ministers of the State, he might all under one bee discharged both from the State and armyes further question or suspicion.” A majority of the committee as thus constituted declared the charges to be without foundation. Three of the officers, a minority of the original committee, for a time dissented from this finding, but eventually, affecting to believe that in a new attack brought against Petty from an unexpected quarter “his Excellency himselfe was strucke att,” they declined to “muddle or make further in the business.”

The scruples of the officers in Ireland were by no means groundless. The death of the Lord Protector had reanimated the purely parliamentarian party of the army in England to an activity that boded no good to his sons. Petty was, throughout his life, a firm supporter of the family of Cromwell, and it was as Henry Cromwell's friend that he had been elected member for West Looe in Richard's parliament. It is not surprising, therefore, that the charges of bribery and breach of trust now preferred against him in the House of Commons by Sir Jerome Sanchey should have appeared to the officers at Dublin as a blow struck at the Lord Deputy himself. A letter from speaker Bampfield brought Sanchey's charges to Petty's

Edition: current; Page: [xx]

attention: On the day set for his reply he appeared in the House and defended himself with great moderation. The charges were vague and there was no proof. In so extensive and difficult a work as the distribution of the army's lands it was inevitable that he should make many enemies, while he had the opportunity to make scarce any friends. He had nothing to conceal. He had often endeavoured to bring himself to a trial, but his adversaries had now done more for him than he was ever able to do for himself: they had brought him to the very fountam of justice and he willingly threw himself into it to be washed of all that was foul and superfluous. The manner of his trial and vindication he committed to the wisdom and justice of the House, asking only that instead of Sanchey's heaps of calumnies and reproach, he might receive a more distinct and particular charge, whereby he might be put in a way to vindicate himself effectually. Sanchey replied in a speech which, as reported by Petty, is remarkable for its violence and incoherence The House lost all patience with him and he was ordered to bring in his charges in writing. The next day, 22 April, Richard Cromwell dissolved Parliament and Petty was once more defrauded of his desired vindication.

Upon the dissolution of Parliament Petty hastened to Ireland, but soon returned to England again, being sent by Henry Cromwell to Fleetwood as one whom he could best trust now his nearest concernments were at stake. Sanchey, now a person of importance in the republican reaction, took advantage of Petty's presence in London to present to the Rump Parliament, 12 July, no less than eleven “new Articles of high misdemeanours, frauds, breach of trusts and several other crimes “chargeable against him. The Rump promptly referred them to the Commissioners for Ireland, before whom they never came to trial. The possibility of an official vindication being thus precluded, Petty resolved to carry his case before the bar of public opinion. With this end in view he published a succinct

Edition: current; Page: [xxi]

account of the dispute with Sanchey down to 13 July, 1659, and the succeeding year he followed it up with a volume of nearly two hundred pages describing the work of survey and distribution, answering the charges brought against him, and explaining how they arose “from the envy and hatred of several parties promiscuously” and “from particular designing persons and parties” in Ireland. About October, 1659, he also prepared for the press, at great length, a History of the Down Survey containing what he regarded as a complete vindication of his conduct, and two further works, now probably lost, upon the same subject.

Among the clubs of the virtuosl to which, as Petty's will relates, it was his privilege to be admitted soon after he came to London, none is more memorable than that company of “capacious and searching spirits inquisitive into natural philosophy and other parts of human knowledge,” whose habit it was to meet for discussion either at Dr Goddard's lodgings in Wood Street or at the Bull's Head Tavern in Cheapside. There is no evidence that Petty was an original member of this company. But it appears probable that he was early invited to join their Invisible College, and it is certain that when parliamentary reorganization of the more visible colleges at Oxford brought Goddard, Wallis, Wilkins, and other followers of

Edition: current; Page: [xxii]

the new philosophy to the venerable home of the old, they there found in Petty an enthusiastic colleague. Their Oxford meetings were held first in his lodgings at the apothecary's because of the convenience of examining drugs and the like when there was an occasion, “and after his removal to Ireland (though not so constantly) at the lodgings of Dr Wilkins.” Those of the company who remained in London meanwhile continued their inquiries in a somewhat desultory manner until the Restoration brought back to the city the more prominent members of the Oxford branch, when it became necessary to change their place of meeting from the Bull's Head to the halls of Gresham College. Here the reunited company was in the habit of assembling for the discussion of questions in natural philosophy. They met regularly on Wednesdays and Thursdays, after the astronomy lectures of Christopher Wren and the geometry lectures of Lawrence Rooke, and on Wednesday, the 28th of November, 1660, after Wren's lecture, the conversation chancing to turn upon foreign institutions for promoting physico-mathematical experimental learning, the company then present, of whom Petty was one, resolved to improve this meeting to a more regular way of debating things and that they might do something answerable and according to the manner in other countryes for the promoting of experimental philosophy. Among those who, in pursuance of this plan, were invited to read papers before the association thus informally organized, Petty's name appears repeatedly, and when, with fitting circumstance, the association was incorporated (15 July, 1662) as the Royal Society for Improving of Natural Knowledge, he was named a charter member of its council.

Petty's famous plan for a “double bottomed” vessel, a sort of catamaran, which should excel in swiftness, weatherliness and stability any “single body” afloat, was probably set forth in one of his papers before the Society. To demonstrate the correctness of

Edition: current; Page: [xxiii]

his views he built at least three such “sluice boats.” The first was laid down at Dublin in 1662. She distinguished herself by beating all the boats in the harbour, and subsequently outsailed the Holyhead packet, the swiftest vessel that the King had there. Hereupon Petty brought her to England, where, probably through the intervention of his friend Pepys, the attention of the Duke of York, then Lord High Admiral, and eventually the notice of the King himself was turned to the novel craft. Charles II. appears to have combined wonder at Petty's energy with quizzical amusement at his numerous projects. He at first chaffed the naviarchal Doctor without mercy, but relented sufficiently to attend the launching of a new Double Bottom which he dubbed “The Experiment.” She also proved herself a swift sailor, but was presently lost in the Irish Channel. This disaster, followed by the burning of several of his London houses in the great fire and by the adverse decisions of some of his Irish law suits, restrained Petty from further shipbuilding experiments for nearly a score of years; but in 1682, while he was considering the establishment at Dublin of a philosophical society similar to that of London, the fit of the Double Bottom, as he tells us, did return very fiercely upon him. His new vessel, however, performed as abominably, as if built on purpose to disappoint in the highest degree every particular that was expected of her and caused him to stagger in much that he had formerly said. But so much did he prefer truth before vanity and imposture that he resolved to spend his life in examining the greatest and noblest of all machines, a ship, and if he found just cause for it to write a book against himself.

The Restoration brought Petty no misfortune. A royal letter dated 2 Jan., 1660, secured to him all lands that he had held on

Edition: current; Page: [xxiv]

the 7th May, 1659, and the Acts of Settlement and of Explanation confirmed them to him by name. Like other owners of forfeited lands in Ireland, he suffered by the operation of the Court of Innocents in 1662, and was never able to convince himself that all who claimed innocency were in fact innocent. But in spite of his losses, he retained large Irish estates, and, in evidence of the King's approval, he was knighted and appears to have been appointed Surveyor-General of Ireland. The duties of this office at the time cannot have been more than nominal, for Petty continued to reside in London. During the Plague he withdrew to Durdens in Surrey where Evelyn found him, with Dr Wilkins and Mr Hooke, busied in contriving mechanical inventions.

In the spring of 1666 Petty was once more called to Ireland by the operations of the Court of Claims, and took up his residence in Dublin. During the ensuing period of his second prolonged stay in Ireland, he thoroughly identified himself with the material interests of that kingdom. As an army physician and surveyor of forfeitures, he had felt himself at most but a sojourner. As a Kerry landholder, able from Mount Mangerton in that country to behold 50,000 acres of his own land, he found abundant occupation, first in defending his titles during the sessions of the Court of Claims, and subsequently in managing his property. The uncertainity of titles in Ireland was great. “The Truth is,” said Essex, “ye Lands of Ireland have bin a meer scramble.” Flaws and defects of various sorts, based on allegations of illegal forfeiture, or of unpaid

Edition: current; Page: [xxv]

quit rents, were being continually found out, and it had become “A principal trade in Ireland to…prevail with persons conversant with the Higher Powers to give grants of these Discoveries, and thereupon, right or wrong, to vex the Prosecutors.” Petty by no means escaped such attacks. He refused to compromise, and in consequence his time was so fully occupied with defending himself that in 1667 he grimly entered “Lawsuits” as his only work accomplished.

Upon his escape from “the fire of this legal purgatory” Petty at once set about the improvement of what remained. His household was established at Dublin, but his most extensive possessions were at Kenmare in Kerry, and there he gradually built up an “industrial colony” of protestants. To this enterprise he gave the closest attention, making the difficult overland journey to that “obscure corner of the world twice a year through thick and thin.” The prospect was not encouraging. His Irish neighbours were hostile, and of Kenmare itself a well informed contemporary reported that while the harbours were very good for ships to load at, the place was so rocky and bare that it would hardly maintain people enough to keep a brogue-maker employed. But there were compensating advantages. The remote bay abounded with salmon. Abundance of wood made charcoal cheap and therefore he established iron and copper works, hoping vainly to discover Irish ores for their supply. The protestant colonists prospered in trade, as he had

Edition: current; Page: [xxvi]

observed the heterodox everywhere to do, and Kenmare clearly demonstrated what thrift, backed by sufficient capital and directed by conspicuous shrewdness, could do for the real settlement of Ireland even under Charles II. After the accession of James II. the colonists fell victims to the jealousy of the surrounding Irish, whose violence was encouraged by Tyrconnel's policy, and thus the most successful of Petty's numerous experiments finally came to naught.

As Petty's stake in the prosperity of Ireland grew larger, his interest in the affairs of the kingdom likewise increased. He had been a member of the Irish parliament of the Restoration, and one of the commissioners appointed to execute the Act of Settlement, he had taken a prominent part in opposing the bill which prohibited the importation of Irish cattle into England, and he had even attempted, though apparently quite ignorant of the law, to fill the position of a judge of admiralty; but the incidental discharge of these public duties had little or no effect upon the subsequent course of his life. His concern with the public revenues of Ireland was far more significant. As early as 1662 he had “frequently applied to present state and affairs of Ireland” certain of the conclusions reached in his “Treatise of Taxes.” To the mere theoretical interest in the subject thus evinced, the events of later years added an interest of a very practical character. In 1668 charges of mismanagement of the Irish revenues were brought against Ormond, the Lord Lieutenant, and Anglesey, the Lord Treasurer, by certain persons who desired to farm the revenues themselves. Their intrigue was successful, and the King agreed with them for seven years from Christmas, 1668, for £219,500 per annum. The management of the new farm was both unsatisfactory to the exchequer and oppressive to the

Edition: current; Page: [xxvii]

subject. Especially did the energy of the farmers in collecting alleged arrears of quit-rents stir the landowners thus charged to active resistance. Among them was Petty. He promptly took up a “legal fight with the farmers,” an account of which occupies for several years a large space in his correspondence with Southwell. His tone makes it evident that a considerable spice of personal animosity was thus added to his previous disgust with the inequalities of Irish taxation and in part explains his subsequent conduct. As the time drew near for the farm of 1668 to expire, he resolved to carry the war into the enemy's camp. Accordingly in the latter part of 1673 he made his way to London and became a bidder, on what he considered a reformed basis, for the new farm beginning Christmas Day, 1675. It appears that an agreement with him was actually made but Ranelagh's influence with Buckingham was sufficient to procure its abrogation and the substitution of the scandalous contract under which Ranelagh, Lord Kingston, and Sir James Shaen continued to mismanage the finances of Ireland until Ormond finally exposed them. Meanwhile Petty remained more than two years in London, renewing his old acquaintances and becoming once more a member of the Council of the Royal Society.

In the summer of 1676 Petty once more took up his residence in Ireland, where, save for visits to London in the spring of 1680, he remained almost five years. It was during this period that he wrote the “Political Anatomy of Ireland,” the “Political Arithmetick,” and the “Observations on the Dublin Bills.” He also fell into a new quarrel with the farmers, the result of which for a time overclouded even his invincible cheerfulness. His chief adversary, Ranelagh, being Chancellor of the Exchequer as well as farmer of

Edition: current; Page: [xxviii]

the taxes, was able to procure his imprisonment for contempt of court. Thus vexed by the wicked works of man, he refreshed himself by pondering the wonderful works of God. The result was a Latin metrical translation of the 104th psalm, copies of which he sent with long complaints to Southwell and to Pepys. But his native whimsically soon reasserted itself. “Lord,” he exclaims, “that a man fifty-four years old should, after thirty-six years discontinuance, return to the making of verses which boys of fifteen years old can correct: and then trouble Clerks of the Council and Secretaries of the Admiralty with them.“

The reappointment of Ormond in 1677 to the Lord Lieutenancy of Ireland, in the room of Essex, whose opinon of Petty was not high brought about a lull in his dispute with the farmers, and after his recovery from the illness which had alarmed him in November of that year, there remained nothing to mar his pleasure in the prosperity of his affairs. He even began to think seriously of the possibility of exercising greater influence in public matters. About the time of his marriage he had been approached concerning a peerage. The condition then suggested was the payment of such a sum as, in view of his recent losses, Petty did not care to spend “in the market of ambition,” and he thanked the royal emissary with scant courtesy. In 1679, when Temple was planning to remodel the Irish Privy Council upon the same lines that he had followed in England and the protestant party at court had marked Petty for appointment to the reconstituted body, the offer of a peerage was again made to him. He seems in the mean time to have changed his opinion of “people who make use of titles and tools” and accordingly he made a journey to London, apparently with the intention of securing both the title and the seat at the

Edition: current; Page: [xxix]

Council table. But Charles II. answered the protestants that by their good leave he would chose his own council for Ireland, and Petty fearing that “a bare title without some trust might seem to the world a body without soul or spirit,” declined the peerage for a second time. Perhaps he consoled himself, as on the previous occasion, by reflecting that he “had rather be a copper farthing of intrinsic value than a brass half-crown, how gaudily soever it be stamped and guilded.”

Upon his return to Ireland, 22 March, 1680, his old controversy with the farmers broke out again, and the vigour of his attack upon their abuses attracted such attention that he was summoned to London in June, 1682, to take part in the discussion then going on before the Privy Council, as to the reorganization of the Irish revenues. He proposed the abolition of the farm, which was finally accomplished, and the imposition of a heavy ale license. Apparently he was not adverse to undertaking the direct collection of the taxes himself, but “by good luck” he “never solicited anybody in the case.” His old rival, Sir James Shaen, now offered to increase the King's revenue nearly £80,000 a year upon a new farm—” a farm indeed, as it was drawn up” says Temple, “not of the revenue but of the crown of Ireland “But the powerful influence of Essex, whom Temple charges with intriguing for a reappoinment to the Lord Lieutenancy, was thrown in Shaen's favour, Petty was represented by some to be a conjurer and by some to be notional and fanciful near up to madness the needs of the Exchequer were urgent, and the plan that promised ready cash was adopted. Deeply disappointed, Petty returned to Ireland in the summer of 1683 and

Edition: current; Page: [xxx]

solaced himself with a journey into Kerry, and presently with a renewal of the experiments that had occupied his mind some twenty years before. He built a new double bottom and was active in the establishment of the Dublin Philosophical Society, for which he wrote several papers.

News of the accession of James II caused Petty to return to London in the early summer of 1685. The new occupant of the royal office had been not less gracious to him than was his predecessor, and Petty fancied the time now ripe to secure for Ireland the adminstrative reforms on which his heart was set. His plans for the revision of the farm and for the establishment, under his own supervision, of an Irish statistical office seemed for a time to be going well, and he attributed undue importance to the interviews which the King granted him upon this and other Irish matters. It was not until later that he appreciated the extent to which, under the new regime, his own personal interests were being drawn to his disadvantage into the larger currents of public affairs. Among the policies which, from time to time, were indistinctly indicated by the vacillations of James II., that looking towards independence of Louis XIV. and the resumption by England of a leading place in the affairs of Europe appealed to Petty with peculiar force. Ten years before, in the “Political Arithmetick,” he had argued England's material fitness for such a place, and had proved, to his own satisfaction at least, that in wealth and strength she was potentially, if not actually, as considerable as France. He now reverted to the same theme, writing a series of essays, in order, by the methods of his political arithmetick, to demonstrate to the satisfaction of the King that London was the greatest city in the world. These efforts excited some attention among the curious, both at home and abroad, but they produced no traceable effect upon the policy of James II.

Petty appears to have realized that independence of France demanded harmony at home, and to have welcomed James's

Edition: current; Page: [xxxi]

Declarations of Indulgence as wise measures for the unification of national sentiment. Knowing as he did the immense material preponderance of the protestant interest both in England and especially in Ireland—a preponderance of which he did his best to convince the King by written and by oral argument—he was unable to believe that the Declarations, whose sentiments quite accorded with his own views were really issued in the sole interest of the Roman Catholics, and he continued to regard the boastings of Tyrconnel and the extreme Irish faction as without foundation in the intentions of the king. But at length tidings of the alarm prevalent among the English protestants in Ireland, and especially the news that McCarthy had been appointed governor of the province of Kerry, brought home to him the danger with which he himself, as well as the other protestants in Ireland, were threatened.

It is not certain whether Petty lived to know that Kenmare was destroyed. For some months he had been unwell. In spite of a “great lameness” he attended the annual dinner of the Royal

Edition: current; Page: [xxxii]

Society on St Andrew's day. He went home ill. His foot gangrened and on December 16 he died at his house in Piccadilly.

On Trinity Sunday, June 2, 1667, Petty had married Elizabeth, daughter of his old friend Sir Hardress Waller, and widow of Sir Maurice Fenton. Though Lady Petty, “a very beautifull and ingeniose lady, browne, with glorious eies,” was much younger than her husband and of a taste as magnificent as his was simple, their married life was most happy. Nowhere does Petty appear to greater advantage than in his letters to his wife, and her letters to him fully bear out Evelyn's judgment, “she was an extraordinary wit as well as beauty and a prudent woman.”

Three of Petty's contemporaries, men of different temperaments and attainments, have put on record their impressions of him. John Aubrey says that he was a proper handsome man, measured six-foot high, with a good head of brown hair moderately turning up. His eyes were a kind of goose-grey, very short sighted and as to aspect beautiful; they promised sweetness of nature and they did not deceive, for he was a marvellous good natured person. His eye-brows were thick, dark and straight, his head very large. Evelyn declared him so exceeding nice in sifting and examining all possible contingencies that he ventured at nothing which is not demonstration. There was not in the whole world his equal for a superintendent of manufactures and improvement of trade, or to govern a plantation. “If I were a prince, I should make him my second counsellor at least. There is nothing difficult to him… Sir William was, with all this, facetious and of easy conversation, friendly and courteous, and had such a faculty of imitating others that he would take a text and preach, now like a grave orthodox divine, then falling into the Presbyterian way, then to the fanatical, the Quaker, the monk and friar, the Popish priest, with such admirable action and alteration of voice and tone, as it was not possible to abstain from wonder, and one would swear to hear several persons, or forbear to think he was not in good earnest an enthusiast and almost beside himself; then,

Edition: current; Page: [xxxiii]

he would fall out of it into a serious discourse; but it was very rarely he would be prevailed on to oblige the company with this faculty, and that only amongst most intimate friends. My Lord Duke of Ormond once obtained it of him, and was almost ravished with admiration; but bye and bye, he fell upon a serious reprimand of the faults and miscarriages of some Princes and Governors, which, though he named none, did so sensibly touch the Duke, who was then Lieutenant of Ireland, that he began to be very uneasy, and wished the spirit laid which he had raised, for he was neither able to endure such truths, nor could he but be delighted. At last, he melted his discourse to a ridiculous subject, and came down from the joint stool on which he had stood; but my lord would not have him preach any more. He never could get favour at Court, because he outwitted all the projectors who came near him. Having never known such another genius, I cannot but mention these particulars, among a multitude of others that I could produce.” And Pepys, who had heard everybody, found Petty “the most rational man that ever he heard speak with a tongue.”

Edition: current; Page: [xxxiv]

GRAUNT'S LIFE.

John Graunt, the author of the “Natural and Political Observations upon the Bills of Mortality” was the son of Henry Graunt, a Hampshire man but a citizen of London, who carried on the business of a draper at the sign of the Seven Stars in Birchin Lane. Of the eight children born to Henry Graunt and Mary, his wife, John, who first saw the light between seven and eight in the morning of April 24th, 1620, was probably the eldest. While a boy he had been educated in English learning and he afterwards acquired Latin and French by studying mornings before shop-time. There is also some indication that he was not lacking in artistic tastes. He was apparently not only the friend of samuel Cooper, the miniaturist, and of the portrait painter John Hayls, but he was also a collector himself. Pepys found his prints “indeed the best collection of anything almost that ever I saw, there being the prints of most of the greatest houses, churches and antiquitys in Italy and France, and brave cutts.” Graunt was bound apprentice to a haberdasher of small wares, and he mostly followed that trade, though free of the Drapers’ Company. That he became a person of standing in his world we have ample assurance. He went through all the offices of the City as far as common council-man, bearing that office two years. He was known as a great peacemaker and was often chosen an arbitrator between disputing merchants. He had, before the completion of his thirtieth year, sufficient influence to secure for his friend Petty the professorship of

Edition: current; Page: [xxxv]

music at Gresham College, and at the time of the Fire he had become “an opulent merchant of London, of great weight and consideration in the city.” So much, in large part but inference, it is still possible to collect concerning the earlier career of John Graunt, citizen and draper. It is, however, to his “Observations upon the Bills of Mortality,” first published in 1662, that Graunt owes whatever posthumous reputation he has attained, and the merit of that book is great enough to entitle him to wider fame than he has achieved.

Why Graunt began his examination of the London Bills, or when, we can but conjecture. He himself speaks of his studies with a certain lightness. Having engaged his thoughts, he knew not by what accident, upon the bills of mortality, he happened to make observations, for he designed them not, which have fallen out to be both political and natural. Thus does Graunt insist, somewhat over-elaborately, upon the casualness of studies which must, in fact, have demanded both time and patience. In the appendix to the third edition, however, after the recognized success of the “Observations” had established their author's position in the scientific world, he speaks with more assurance of his “long and serious perusal of all the bills of mortality which this great city hath afforded for almost four score years.” This is certainly in strong contrast not only to the apologetic air of the original dedication, but also to the care with which, in the preface to the first edition, the tradesman-author excused himself, as it were, to the philosophers of Gresham College, for his presumption in invading the field of scientific investigation. He had observed that the weekly bills were put by those who took them in to little use other than to furnish a text to talk upon in the next company; and he “thought that the Wisdom of our City had certainly designed in the laudable practice of taking and distributing these Accompts for other and greater uses…or at least that some other uses might be made of them.” It is probably to the latter suggestion, supplied perhaps by his friend Petty, and perhaps by Graunt's own “excellent working head,” rather than to his belief in the prescience of the corporation of London that we owe the writing of the “Observations.”

Edition: current; Page: [xxxvi]

The preface to the first edition of the “Observations” is dated 25 January, 166½. They met apparently a favourable reception. Before they had been in print two months, Pepys, ever alert to hear some new thing, was buying a copy at Westminster Hall. To others, as to him, they must have “appeared at first sight to be very pretty,” for a new edition was called for within the year. The greatest compliment however, which Graunt received on account of his book, and doubtless the compliment which he most appreciated, was his election into the Royal Society. The 5th February, 1662, fifty copies of the “Observations” were presented by Dr Whistler on behalf of the author to the “Society of Philosophers meeting at Gresham Colledg.” The epistle dedicatory to their president, Sir Robert Moray, was at once read, whereupon thanks were ordered to be returned to Graunt, and he was proposed a candidate. Bishop Sprat says that Graunt was recommended to the Royal Society—for as such the Society of Philosophers were presently incorporated—by no one less than the King himself, and that “in his election it was so far from being a prejudice that he was a shopkeeper of London, that His Majesty gave this particular charge to His Society, that if they found any more such tradesmen, they should be sure to admit them all, without any more ado.” The Society, however, seems to have had, even thus early in its history, a fitting sense of its own dignity. At any rate it took adequate precautions that Graunt be not admitted until his fitness for membership had been established beyond question. On the 12th February a formidable committee, composed of Sir William Petty, Dr Needham, Dr Wilkins, Dr Goddard, Dr Whistler, and Dr Ent, was appointed to examine the book. Their report is not preserved by Birch, but it must have been favourable, for 26th February Graunt was elected a fellow of the Society. In spite of his assertion, in the epistle dedicatory to Sir Robert Moray, that he was none of their number nor had the least ambition to be so, Graunt promptly accepted the election and subscribed his name at the next meeting of the Society. His connection with the Royal Society appears to have been, on the whole, rather formal than vital. He was, indeed, for some five years after his election a frequent attendant at its meetings, he proposed

Edition: current; Page: [xxxvii]

one candidate, Sir John Portman, for election as a member, he served on several committees, and he was even a member of the Council of the Society from 30 Nov., 1664 to 11 April, 1666. He took, however, but small part in the scientific proceedings. Only once did he make a communication in any way similar to his “Observations,” and in that communication, although he spoke of the rapid increase of carp by generation, what obviously interested him was not, as we might have expected, the increase of the fish in numbers, but rather their growth in size.

The disappearance of Graunt's name from the minutes of the Royal Society's meetings after 1666 must be accounted one of the results of his large losses by the Fire of London. Even with the substantial assistance of his devoted friend Petty, Graunt could not recover from the business reverses he then sustained. His conversion from protestantism to the Roman Catholic Church seems also to have worked to his disadvantage in worldly matters, and his affairs went from bad to worse until his death, 18 April, 1674. He was buried in St Dunstan's church, Fleet Street. “A great number of ingeniose persons attended him to his grave. Among others, with teares, was that great ingeniose virtuoso, Sir William Petty.”

Of the esteem in which John Graunt was held by his contemporaries we have sufficient evidence. His old acquaintance Richard Smith, the famous book-collector, esteemed him “an understanding man of quick witt and a pretty schollar.” Pepys, who also knew him well, considered his “most excellent discourses” well worth hearing.” Aubrey, who had found him “a pleasant facetious companion and very hospitable,” declares that “his death was lamented

Edition: current; Page: [xxxviii]

by all good men that had the happinesse to knowe him.” And Anthony à-Wood, professing to give only “an exact history of all the bishops and writers who have had their education in the most antient and famous University of Oxford,” goes out of his way to append to a sketch of Edward Grant, the classicist, an account of this man who owed his education to no university. The account begins with these enthusiastic words, “Now that I am got into the name of Grant I cannot without the guilt of concealment but let you know some things of the most ingenious person, considering his education and employment, that his time hath produced.… The said John Graunt was an ingenious and studious person, generally beloved, was a faithful friend, a great peace-maker, and one that had often been chosen for his prudence and justness an arbitrator. But above all his excellent working head was much commended, and rather for this reason, that it was for the public good of learning, which is very rare in a trader or mechanic.”

Edition: current; Page: [xxxix]

THE AUTHORSHIP OF THE NATURAL AND POLITICAL OBSERVATIONS UPON THE BILLS OF MORTALITY.

Concerning the authorship of the “Natural and Political Observations upon the Bills of Mortality “there seems at first to be no possibility of raising a question. Their title-page bears the name of Captain John Graunt, and the preface gives a plausible account of the manner in which he came to write them. At the time of their publication he was commonly reputed their author. Because of this repute he was elected a member of the Royal Society, and he accepted the membership. Such conduct by such a man would seem to leave no room for doubt that he was the author of the book issued under his name. There are, nevertheless, certain grounds for thinking that the book was in fact written not by Graunt, but by Sir William Petty. Persons who knew one or both of them have asserted that Petty was the author, and later writers have added certain lines of argument to the same- effect, based on internal evidence and on corroborative probabilities.

The first of Petty's friends to assert his authorship of the London Observations was John Evelyn.

In his diary, under date of March 22, 1675, Evelyn wrote:

Supp'd at S’ William Petty's with the Bp of Salisbury and divers honorable persons. We had a noble entertainment in a house gloriously furnish'd; the master and mistress of it were extraordinary persons.… He is the author of the ingenious deductions from the bills of mortality, which go under the name of Mr Graunt; also of that useful discourse of

Edition: current; Page: [xl]

the manufacture of wool, and several others in the register of the Royal Society. He was also author of that paraphrase on the 104th Psalm in Latin verse, which goes about in MS. and is inimitable. In a word, there is nothing impenetrable to him.

The next witness for Petty—and also against him—is his intimate friend, John Aubrey, the antiquary. Aubrey assisted Anthony à-Wood in the compilation of his “Athenæ Oxonienses” by furnishing him a number of “minutes of lives.” From his letters to Wood concerning them, it appears that Aubrey began his sketch of Petty in February, 1680, and that shortly before March 27, “Sir W. P. perused my copie all over & would have all stand.” The chaotic condition of Aubrey's notes renders it impossible to say how much of the manuscript now in the Bodleian Library was approved by Petty, but it seems not improbable that Aubrey showed him folios 13 and 14, bringing the narrative down to Petty's departure for Ireland, 22 March, 1680. If so, we have Petty's approval of the statement (on folio 14) that he was elected professor in Gresham College by the interest of “his friend captaine John Graunt (who wrote the Observations on the Bills of Mortality).” In June, 1680, Aubrey sent this manuscript to Wood, but he appears to have recalled it, about ten years later, for the purpose of making additions and corrections. To this later period at least a portion of the memoranda on folio 15 must be assigned, for one of them speaks of certain matters subsequent to Petty's death (1687) which have already escaped Aubrey's memory, It is not so clear that the very incomplete catalogue of Petty's writings on folio 15 was likewise added after the return of the manuscript to Aubrey, since there stand opposite two of the titles mentioned in it notes by Wood telling where copies of the books may be found. Still it is at least probable that this, like what immediately follows it on the same folio, was added by Aubrey after Petty had perused his copy all over. And the probability is heightened by the presence on folio 15 of an assertion directly contradictory to what Petty had approved in 1680. Near the end of the list of Petty's writings Aubrey writes, “Observations on the Bills of Mortality were really his.”

The third witness for Petty is Edmund Halley. Halley was the most famous of English students of the Bills of Mortality, and the

Edition: current; Page: [xli]

vast results that have flowed from his “Estimate of the Degrees of Mortality of Mankind “predispose us to regard as authoritative anything that he may have said as to the work of his predecessors. It should be remembered, however, that Halley was a much younger man than Petty and did not become a member of the Royal Society until five years after Graunt's death. His famous memoir begins with these words:

The contemplation of the mortality of mankind has, besides the moral, its physical and political uses, both which have some time since been most judiciously considered by the curious Sir William Petty, in his moral and political Observations upon the Bills of Mortality of London, owned by Captain John Graunt. And since in a like treatise on the Bills of Mortality of Dublin.… But the deductions from those bills of mortality seemed even to their authors [sic] to be defective.

Bishop Burnet, the fourth of Petty's contemporaries to assert his authorship of the Observations, had no such interest in them as did Halley indeed his allusion to the subject is merely casual. In the first volume of his “History of his own Time,” published in 1723, but probably written before 1705, he makes the charge that Graunt, being a member of the New River Company, stopped the pipes at Islington the night before the London fire, September 2, 1666. Burnet's account of this alleged occurrence begins: “There was one Graunt, a papist, under whose name Sir William Petty published his observations on the bills of mortality.”

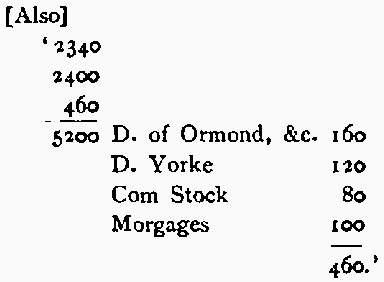

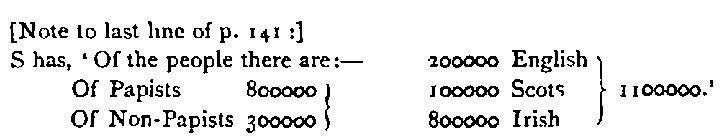

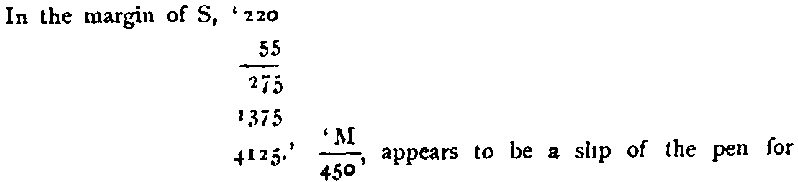

Such is the direct testimony for Petty. The direct testimony in favour of Graunt comes from five sources. First, from the work whose authorship is in issue. Four editions of the “Observations” published during his lifetime and one published by Petty after Graunt's death, all bear on their title-pages Graunt's name as author. Second, Petty's own testimony in his books and in his private correspondence. In his acknowledged writings he mentions the Observations at least seventeen times. In nine of these instances Graunt's name is mentioned, in seven he is not named, and in the remaining case, the “Political Arithmetick,” as printed in 1690, makes Petty speak of “the observators upon the bills of mortality.”

Edition: current; Page: [xlii]

Since the “Political Arithmetick” was written in 1676, i.e., before Petty's own “Observations upon the Dublin Bills,” this expression might be construed as a claim by Petty to a share in the authorship of the “Observations” of 1662. But reference to the Southwell and the Rawlinson manuscripts of the “Political Arithmetick” in the Bodleian Library, bearing Petty's autograph corrections, shows conclusively that he here intended to set up no such claim. Moreover, in a private letter, to his most intimate friend and relative, Sir Robert Southwell (August 20, 1681), Petty twice speaks of “Graunt's” and once of “our friend Graunt's” book.

In contrast with Petty's direct testimony to Graunt's authorship of the London “Observations” stands the title-page of his statistical firstling, the Dublin “Observations” (1683), which reads “By the Observator on the London Bills of Mortality.” This might be construed as claiming the London Observations for Petty, but an explanation at least equally plausible would make it a mere bookseller's trick of Mark Pardoe, the publisher, to commend the Dublin “Observations” to a public that had recently greeted a fifth edition of the London “Observations” with favour. The device, if such it were, appears to have failed, for Pardoe had sheets of the Dublin “Observations” still on hand in 1686, and when he reissued them, with additions, as a “Further Observation on the Dublin Bills,” Petty's name appeared on the title-page, without any mention of the London “Observations.” Nor did the change occur here alone. In the first (1683) edition of “Another Essay in Political Arithmetick. By Sir William Petty,” the original Dublin “Observations” are advertised as “by the Observator on the London Bills of Mortality.” In the second edition of the Essay, published in 1686, but before the “Further Observation,” the advertisement of the original Dublin “Observations” reads: “By Sir William Petty.”

Contemporary testimony in favour of Graunt comes, thirdly, from the Royal Society and from various members of it. The circumstances of his election have been recounted in the preceding section. The opinion of the Society and of its historian as there

Edition: current; Page: [xliii]

expressed was later confirmed by its Secretary. During the Plague Oldenburg wrote from London:

Though we had some abatement in our last week's bill, yet we are much afraid it will run as high this week as ever. Mr Graunt, in his appendix to his Observations upon those bills (now reprinted) takes notice, that forasmuch as the people of London have, from Anno 1625 to this time, increased from eight to thirteen, so the mortality shall not exceed that of 1625, except the burials should exceed 8400 per week.

The case for Graunt is further strengthened by the testimony of John Bell, clerk of the Company of Parish Clerks. The author of the “Observations” asserts that he visited the hall of the Parish Clerks, and used their records in the preparation of his book. Bell, therefore, who was in charge of the Clerks'register, could scarcely have been deceived as to his identity. Now in London's Remembrancer, after explaining and defending the manner in which the bills of mortality were prepared by the Company of Parish Clerks, Bell proceeds:

I think I need not trouble myself herein [i.e., in describing the form of the bills], since that worthy and ingenious Gentleman, Captain John Graunt, in his Book of Natural and Political Observations on the Bills of Mortality, hath already so well described them.

The last of the witnesses in the case is Sir Peter Pett. Born, probably, in 1627, a member of Oxford University while Petty was there, a charter fellow of the Royal Society, Pett was a life-long friend of Sir William, and it is probable that he knew Graunt also. In 1688 Pett published a folio volume designed to vindicate the Earl of Anglesey from the charge of being a Roman Catholic. This gigantic pamphlet discusses many matters not germane to the charge

Edition: current; Page: [xliv]

against Anglesey, and among them England's growth in population. In the course of the discussion Pett alludes four times to the London“Observations,” but without mentioning the name of either Petty or Graunt:

If any of our monkish historians… had given the world rational estimates of the numbers of… the males then between the years of 16 and 60 [from the military returns]… we might now easily by the help we have from the Observator on the Bills of Mortality conclude, what the entire number of the people then was. [page 91.]

T is very remarkable that in the Code Louys which he [Louis XIV.] published in April, 1667, he made some ordinances with great care for the registring the christenings and marriages and burials, in each Parish… having perhaps been informed by his ministers that many political inferences, as to the knowing the number of people and their encrease in any state, are to be made from the bills of mortality, on the occasion of some such published about 3 years before by the Observator on the Bills of Mortality in England. [Pages 248–249.]

It must be acknowledged that the thanks of the age are due to the Observator on the Bills of Mortality, for those solid and rational calculations he hath brought to light, relating to the numbers of our people: but such is the modesty of that excellent author that I have often heard him wish that a thing of so great publick importance to be certainly known, might be so by an actual numbering of them…. Mr James Howel… saith, that in the year 1636… the Lord Mayor of London… took occasion to make a cense of all the people and that there were of men, women and children, above 7 hundred thousand that lived within the barrs of his jurisdiction alone… and… more now… But I am to suspect that there was no such return in the year 1636… and do suppose that Mr Howel did in that point mistake… partly because I find it mentioned by the curious Observator on the Bills of Mortality, p.113 and 114 [of the 1676 ed.] that anno 1631, ann. 7 Caroli I. the number of men, women and children in the several wards of London and liberties… came in all to but 130178, and finally because the said curious Observator (for that name I give that author after My Lord Chief Justice Hales[sic]hath given or adjudged it to him in his Origination of Mankind) having by rational calculations proved that there dyes within the Bills of Mortality a thirtieth part, or one in thirty yearly, and that there dies there 22000 per annum…. If there were there according to Howel a million and a half people, it would follow that there must dye but I out of 70 per annum.[Pages 112-113.]

We are told by the Observator on the Bills of Mortality, that anxiety of mind hinders Breeding, and from sharp anxieties of divers kinds hath the Protestant Religion rescued English minds.[Page 119.]

Edition: current; Page: [xlv]

In these passages from Pett two peculiarities need to be explained. The first is the omission of Petty's name. If Pett regarded Petty as the author of the “Observations,” why should he consistently omit to mention him here as “Sir W. P.”—a form of reference which he repeatedly uses when speaking elsewhere of Petty's other works? The second fact to be explained is Pett's manifest desire to avoid mentioning by name “that excellent author,” “the most curious Observator.” It certainly is not by chance that Pett, whose laborious book is a medley of duly credited extracts from almost all English and classical literature, instead of mentioning the author of the “Observations,” here carefully took refuge behind a quotation—or rather a misquotation—from Sir Matthew Hale. I believe that Pett's peculiar course at this point can be best explained on the assumption that he considered Graunt the author of the work. He was attempting, at a time when Oates’ absurd stories of the popish plot were still heartily believed, to vindicate Anglesey from the charge of leaning towards Roman Catholicism. He was therefore careful not to betray any sympathy with the Romanists. Now according to Wood, when Graunt had been a major two or three years, he

then laid down his trade and all public employments upon account of religion. For though he was puritanically bred, and had several years taken sermon-notes by his most dextrous and incomparable faculty in short-writings and afterwards did profess himself for some time a Socinian, yet in his later days he turned Roman Catholic, in which persuasion he zealously lived for some time and died.

May not this explain Pett's obvious unwillingness to praise the author of the “Observations,” Graunt, by name? Pett does not afford demonstration, but he furnishes corroboration.

The second line of argument includes all appeals to internal evidence, whether advanced by supporters of Graunt or of Petty. Here again the supporters of Petty shall speak first. Between parts of the “Observations” and portions of his acknowledged writings

Edition: current; Page: [xlvi]

they find numerous similarities so striking as to constitute, in the opinion of Dr Bevan, an effective way of testing the question of authorship. An examination of these parallel passages reveals their very unequal significance for the present discussion. For example, the remark in both the London “Observations” and the “Treatise of Taxes” concerning the causes of the westward growth of London cannot be used to establish their common authorship, John Evelyn having set the idea afloat in the preceding year. In like manner the talk about equalizing the parishes was a current commonplace of the Restoration. On the other hand the remaining parallels, especially that between Graunt's Conclusion (pp. 395–397, post) and various passages in Petty's writings, are doubtless important.

In addition to these parallel passages, other bits of internal evidence have been adduced by the supporters of Petty. “The most notable thing in the first few pages of the ‘Bills,’” says Dr Bevan, “is the amount of space devoted to a description of different diseases. They are described with a familiarity and precision which only a physician could be expected to have.” Upon a layman the discussions in chapters two and three of the similarities between rickets and liver-growth, and between the green sickness, stopping of the stomach, mother, and rising of the lights, undoubtedly make a learned impression. Whether they were in fact the discussions of a learned or of an ignorant man, a specialist

Edition: current; Page: [xlvii]

in the history of English medicine before Sydenham could probably say. But one need not be a medical antiquarian to see that, in the most elaborate of these discussions, the one concerning rickets and liver growth, and indeed, throughout all the discussions of this sort, the method of the writer of the “Observations” is distinctly statistical, is marked, indeed, by considerable statistical acuteness, and is scarcely at all diagnostic or pathological, as a physician's method, nowadays at any rate, would probably be. He enquires whether the same disease has been returned in different years under different rubrics; and he finds his answer by investigating the fluctuations from year to year in the number of deaths from each. Moreover, it is in the midst of these discussions of diseases that the variations in the number of those who died of rickets from year to year provokes this curious passage:

Now, such back-startings seem to be universal in all things; for we do not only see in the progressive motion of wheels of Watches, and in the rowing of Boats, that there is a little starting or jerking backwards between every step forwards, but also (if I am not much deceived) there appeared the like in the motion of the Moon, which in the long Telescopes at Gresham College one may sensibly discern. [Page 358 post.]

De Morgan points out the improbability that “that excellent machinist, Sir William Petty, who passed his day among the astronomers,” should attribute to the motion of the moon in her orbit all the tremors which she gets from a shaky telescope.

Other peculiarities of the “Observations” which are held by Dr Bevan to indicate Petty's authorship are the “references to Ireland derived apparently from personal observation,” and the fact that “Hampshire, Petty's native county, is the only English county mentioned.” The latter inference might have been made much stronger for Petty. The author of the “Observations” bases many of his most interesting conclusions upon a comparison between the tables of London mortality and the “Table of a Country Parish,” and this country table is unquestionably derived from the parish register of the Abbey of St mary and St Ethelfleda, at Romsey, the

Edition: current; Page: [xlviii]

church in which Petty's baptism is recorded and in which he lies buried. But the fact by no means implies Petty's authorship of the “Observations.” It is not less reasonable to suppose that Graunt, when studying the London bills, applied to Petty for such comparative material as he afterwards sought from four other friends in various parts of England. As for the allusions to Ireland, they indicate rather that the author had not been in that kingdom at all than that he had made personal observations there. One of them is a casual remark in connection with his belief that deaths in child-bed are abnormally frequent “in these countries where women hinder the facility of their child-bearing by affected straitening of their bodies… What I have heard of the Irish women confirms me herein.” In the other passage the author says “I have heard,… I have also heard” this and that about Ireland.

Those who have agreed that Graunt was the author of the “Observations,” need not leave to their opponents the exclusive use of internal evidence. They, for their part, may first point out that there are considerable differences of language between Petty's works and Graunt's. Every one at all familiar with seventeenth-century English pamphlets has sympathized with Sir Thomas Browne's solicitude lest “if elegancy still proceedeth, and English pens maintain that stream, which we have of late observed to flow from many, we shall within few years be fain to learn Latin to understand English.” Petty's “Reflections” and his “Treatise of Taxes and Contributions” are of about the same size as the “Observations.” I have run through all three and counted the Latin words, phrases and quotations, excluding those which, like anno, per annum, per centum, are virtually English. The “Reflections,” in the 154 pages which are indisputably by Petty, contain at least twenty-four Latin phrases, the “Treatise” at least forty-two. The “Observations” show, aside from the sentiment on the title-page, but six Latin phrases; and of the six, three are within as many pages of the “Conclusion” (pages 395–397, post) in precisely the passage which exhibits the

Edition: current; Page: [xlix]

most conspicuous of all the parallels between the “Observations” and the “Treatise.”

The supporters of Graunt may properly claim, in the second place—and upon this they may insist, since heretofore it has not received adequate emphasis—that the statistical method of the “Observations” is greatly superior to the method of Petty's acknowledged writings upon similar subjects. Graunt exhibits a patience in investigation, a care in checking his results in every possible way, a reserve in making inferences, and a caution about mistaking calculation for enumeration, which do not characterize Petty's work to a like degree. This difference cannot escape any person of statistical training who may read carefully first the “Observations” and then Petty's “Essays.”

In the third place, it deserves to be noted that the chief parallels to Petty's writings do not occur in parts of the “Observations” which are vital or organic. In his patient investigations of the movement of London's population, imperfect and frequently erroneous though they were, and, for lack of data, necessarily must have been the author of the “Observations” displays admirable traits for which Petty's writings, however meritorious otherwise, may still be searched in vain. The passages in which the parallels occur are, as it were, the embroideries with which Graunt's solid work is decorated—possibly by Petty's hand. For example, the passage concerning beggars and charity in Holland is appended to the contention that, since “of the 229,250, which have died, we find not above fifty-one to have been starved, except helpless infants at nurse,” therefore there can be no “want of food in the country, or of means to get it.” The argument is statistical; the appended passage about beggars is not. It has no real connection, and if it were omitted, the argument proper would lose nothing of its cogency. The longest and closest parallel between the “Observations” and the “Treatise” is of like character. It occurs in and indeed pervades “The Conclusion.” And this conclusion, instead of offering, as one might expect, a sober summary in the style of the book itself,

Edition: current; Page: [l]

is an obvious and, one must own, a not altogether unsuccessful attempt “to write wittily about these matters.”

The third group of arguments—those based upon the probabilities of the case—should be considered as corroborative, rather than as of independent weight. In advancing them the partisans of each writer must seek to strengthen a case already built up by direct testimony and internal evidence rather than to establish their contentions ab initio. In general, the probabilities strongly favour Graunt. In the first place, he was a citizen and a native of London. He thus had opportunity to collect the bills and incentive to study them; and the author's account of the way in which he came to make the study tallies in every particular with the known facts of Graunt's life. Petty, on the other hand, was of provincial birth, and had been a resident of London but a short time when the “Observations” were published. In the second place, the “Observations” are not the product of a few leisure hours, or even of a few hurried weeks. Their laborious compilation demanded time—how much, those will best appreciate who have attempted similar tasks. Graunt may well have had the necessary leisure, whereas Petty, in defending his Irish survey, in writing for the Royal Society, and in working for political self-advancement at the Restoration, must have been otherwise well occupied during the years 1660 and 1661. In the third place, the assumption that a man of Graunt's standing in the city would consent to be a screen for Petty's book, has never been put upon a sound basis, or indeed upon any basis at all. Finally it may be noted that the “Observations” contained nothing offensive; they were not only novel, but popular, and it was by no means Petty's nature to refuse credit for a good thing which he had done. Nevertheless the “Observations” had been out almost fifteen years, had passed through four editions, and had received unusual honours at the hands of the Royal Society, and apparently of the king also, before there was a whisper of Petty's authorship.

Opposed to these probabilities in favour of Graunt stand two analogous arguments for Petty. One argument Dr Bevan advances:

Edition: current; Page: [li]

“We are not able to assign a reason for Petty's wish to conceal his authorship under the name of a friend, but we do know that several of his works were published anonymously during his lifetime.” It need scarcely be said that publishing a book anonymously is a different thing from publishing it under the name of somebody else—and that somebody a well-known man. The other argument is put by Mr Hodge in these words:

If I were disposed to argue the matter upon probabilities, I might ask what other proof Graunt gave of his capacity for writing such a work…. It is certainly strange, if Graunt were the man, that he should have stopped short after having made such a remarkable step. Of Petty's abilities for dealing with the subject it is unnecessary to speak.

The argument that Graunt cannot have written one book because he did not write a second, is scarcely of a cogency sufficient to prevail against the favourable opinion of those who knew him. Aubrey had a very high opinion of his abilities, and Pepys, who seems also to have known him well, accepted his authorship without the slightest hesitation.