INTRODUCTION

The Organ Chorals

Bach’s lavish use of Lutheran hymnody has been pointed out in Part II of this work. One hundred and thirty-two melodies are treated by him, either in his concerted Church music or in the Organ works, without taking into account hymn tunes of which there are four-part settings among the “Choralgesänge.” Of the one hundred and thirty-two, seventy-seven are in the Organ works, twenty-eight of which are not used in the Cantatas, Oratorios, or Motetts. On these seventy-seven tunes Bach constructed one hundred and forty-three authentic Organ movements, or sets of movements, distributed thus: in the Orgelbüchlein 46; in Part III of the Clavierübung 17; in the Eighteen Chorals 18; in the Schübler Chorals 6; Variations or Partite 4; miscellaneous or ungrouped Preludes 52.

The following Table names the seventy-seven melodies and the one hundred and forty-three Edition: current; Page: [2] movements built upon them. The distinguishing capital letters have the following signification:

| C. |

stands for the |

Clavierübung, Part III. |

| E. |

stands for the |

Eighteen Chorals. |

| M. |

stands for the |

Miscellaneous or ungrouped Preludes. |

| O. |

stands for the |

Orgelbüchlein. |

| S. |

stands for the |

Schubler Chorals. |

| V. |

stands for the |

Variations or Partite. |

For convenience, page and volume references are given to the four Editions: B.G. stands for the Bachgesellschaft; B.H. for Breitkopf and Haertel; N. for Novello; P. for Peters. Elsewhere in this volume reference is given exclusively to the Novello Edition. A collation of the Peters and Novello Editions will be found at pp. 294-302 of the present writer’s Johann Sebastian Bach (Constable: 1920).

1. Ach bleib’ bei uns, Herr Jesu Christ.

S. 1. N. xvi. 10. B.G. xxv. (2) 71. P. vi. 4. B.H. viii. 2.

2. Ach Gott und Herr.

M. 2. N. xviii. 1. B.G. xl. 4. P. ix. 38. B.H. viii. 5.

A variant of the movement is in B.G. xl. 152.

M. 3. N. xviii. 2. B.G. xl. 5. P. vi. 3. B.H. viii. 6.

M. 4. N. xviii. 3. B.G. xl. 43. P. ix. 39. B.H. viii. 7.

3. Ach wie flüchtig.

O. 5. N. xv. 121. B.G. xxv. (2) 60. P. v. 2. B.H. vii. 3.

4. Alle Menschen müssen sterben.

O. 6. N. xv. 119. B.G. xxv. (2) 59. P. v. 2. B.H. vii. 4.

Edition: current; Page: [3]

5. Allein Gott in der Höh’ sei Ehr’.

C. 7. N. xvi. 39. B.G. iii. 197. P. vi. 10. B.H. viii. 8.

C. 8. N. xvi. 40*. B.G. iii. 199. P. vi. 12. B.H. viii. 18.

An older text is in B.G. xl. 208 and P. vi. 96.

C. 9. N. xvi. 41. B.G. iii. 205. P. vi. 29. B.H. viii. 29.

E. 10. N. xvii. 56. B.G. xxv. (2) 122. P. vi. 26. B.H. viii. 36.

E. 11. N. xvii. 60. B.G. xxv. (2) 125. P. vi. 22. B.H. viii. 24.

An older text is in B.G. xxv. (2) 180 and P. vi. 100.

E. 12. N. xvii. 66. B.G. xxv. (2) 130. P. vi. 17. B.H. viii. 30.

An older text is in B.G. xxv. (2) 183 and P. vi. 97.

M. 13. N. xviii. 4. B.G. xl. 44. B.H. viii. 11.

M. 14. N. xviii. 5. B.G. xl. 34. P. vi. 6. B.H. viii. 12.

M. 15. N. xviii. 7. B.G. xl. 45. P. vi. 30. B.H. viii. 14.

M. 16. N. xviii. 11. B.G. xl. 47. P. vi. 8. B.H. viii. 16.

A set of seventeen Variations, of doubtful genuineness, is in B.G. xl. 195.

6. An Wasserflüssen Babylon.

E. 17. N. xvii. 18. B.G. xxv. (2) 92. P. vi. 34. B.H. viii. 40.

An older text is in B.G. xxv. (2) 157 and P. vi. 103.

M. 18. N. xviii. 13. B.G. xl. 49. P. vi. 32. B.H. viii. 43.

7. Aus tiefer Noth schrei ich zu dir.

C. 19. N. xvi. 68. B.G. iii. 229. P. vi. 36. B.H. viii. 46.

C. 20. N. xvi. 72. B.G. iii. 232. P. vi. 38. B.H. viii. 48.

8. Christ, der du bist der helle Tag.

V. 21. N. xix. 36. B.G. xl. 107. P. v. 60. B.H. vii. 58.

9. Christ ist erstanden.

O. 22. N. xv. 83. B.G. xxv. (2) 40. P. v. 4. B.H. vii. 6.

A four-part setting is in B.G. xl. 173.

10. Christ lag in Todesbanden.

O. 23. N. xv. 79. B.G. xxv. (2) 38. P. v. 7. B.H. vii. 10.

M. 24. N. xviii. 16. B.G. xl. 10. P. vi. 43. B.H. viii. 51.

A variant reading is in B.G. xl. 153 and P. vi. 104.

M. 25. N. xviii. 19. B.G. xl. 52. P. vi. 40. B.H. viii. 54.

A movement of doubtful authenticity is in B.G. xl. 174 and P. ix. 56.

Edition: current; Page: [4]

11. Christ unser Herr zum Jordan kam.

C. 26. N. xvi. 62. B.G. iii. 224. P. vi. 46. B.H. viii. 58.

C. 27. N. xvi. 67. B.G. iii. 228. P. vi. 49. B.H. viii. 63.

12. Christe, du Lamm Gottes.

O. 28. N. xv. 61. B.G. xxv. (2) 30. P. v. 3. B.H. vii. 5.

13. Christum wir sollen loben schon.

O. 29. N. xv. 33. B.G. xxv. (2) 15. P. v. 8. B.H. vii. 11.

M. 30. N. xviii. 23. B.G. xl. 13. P. v. 9. B.H. viii. 58.

This movement has the alternative title, “Was fürcht’st du, Feind Herodes, sehr.”

14. Christus, der uns selig macht.

O. 31. N. xv. 64. B.G. xxv. (2) 30. P. v. 10. B.H. vii. 12.

An older text is in B.G. xxv. (2) 149 and P. v. 108.

15. Da Jesus an dem Kreuze stund.

O. 32. N. xv. 67. B.G. xxv. (2) 32. P. v. 11. B.H. vii. 14.

16. Das alte Jahr vergangen ist.

O. 33. N. xv. 43. B.G. xxv. (2) 19. P. v. 12. B.H. vii. 15.

17. Das Jesulein soll doch mein Trost.

M. 34. N. xviii. 24. B.G. xl. 20. P. ix. 47. B.H. viii. 64.

18. Der Tag, der ist so freudenreich.

O. 35. N. xv. 18. B.G. xxv. (2) 8. P. v. 13. B.H. vii. 16.

M. 36. N. xviii. 26. B.G. xl. 55. B.H. viii. 66.

19. Dies sind die heil’gen zehn Gebot’.

O. 37. N. xv. 103. B.G. xxv. (2) 50. P. v. 14. B.H. vii. 18.

C. 38. N. xvi. 42. B.G. iii. 206. P. vi. 50. B.H. viii. 68.

C. 39. N. xvi. 47. B.G. iii. 210. P. vi. 54. B.H. viii. 72.

20. Durch Adams Fall ist ganz verderbt.

O. 40. N. xv. 107. B.G. xxv. (2) 53. P. v. 15. B.H. vii. 20.

M. 41. N. xviii. 28. B.G. xl. 23. P. vi. 56. B.H. viii. 74.

21. Ein’ feste Burg ist unser Gott.

M. 42. N. xviii. 30. B.G. xl. 57. P. vi. 58. B.H. viii. 76.

Edition: current; Page: [5]

22. Erbarm’ dich mein, O Herre Gott.

M. 43. N. xviii. 35. B.G. xl. 60. B.H. viii. 80.

23. Erschienen ist der herrliche Tag.

O. 44. N. xv. 91. B.G. xxv. (2) 45. P. v. 17. B.H. vii. 21.

24. Erstanden ist der heil’ge Christ.

O. 45. N. xv. 89. B.G. xxv. (2) 44. P. v. 16. B.H. vii. 22.

25. Es ist das Heil uns kommen her.

O. 46. N. xv. 109. B.G. xxv. (2) 54. P. v. 18. B.H. vii. 23.

26. Gelobet seist du, Jesu Christ.

O. 47. N. xv. 15. B.G. xxv. (2) 7. P. v. 19. B.H. vii. 24.

M. 48. N. xviii. 37. B.G. xl. 62. P. v. 102. B.H. viii. 81.

A variant is in B.G. xl. 158.

M. 49. N. xviii. 38. B.G. xl. 14. P. v. 20. B.H. viii. 82.

M. 50. N. xviii. 39. B.G. xl. 63. P. vi. 61. B.H. viii. 83.

27. Gottes Sohn ist kommen.

O. 51. N. xv. 5. B.G. xxv. (2) 4. P. v. 20. B.H. vii. 24.

To this movement Bach gives the alternative title, “Gott, durch deine Gute.”

M. 52. N. xviii. 41. B.G. xl. 21. P. v. 22. B.H. viii. 85.

M. 53. N. xviii. 42. B.G. xl. 65. P. vi. 64. B.H. viii. 86.

28. Helft mir Gott’s Gute preisen.

O. 54. N. xv. 39. B.G. xxv. (2) 18. P. v. 23. B.H. vii. 26.

29. Herr Christ, der ein’ge Gottes-Sohn.

O. 55. N. xv. 9. B.G. xxv. (2) 5. P. v. 24. B.H. vii. 27.

To this movement Bach gives the alternative title, “Herr Gott, nun sei gepreiset.”

M. 56. N. xviii. 43. B.G. xl. 15. P. v. 25. B.H. viii. 87.

A simple four-part setting of the melody is in P. v. 107.

30. Herr Gott dich loben wir.

M. 57. N. xviii. 44. B.G. xl. 66. P. vi. 65. B.H. viii. 88.

31. Herr Gott, nun schleuss den Himmel auf.

O. 58. N. xv. 53. B.G. xxv. (2) 26. P. v. 26. B.H. vii. 28.

Edition: current; Page: [6]

32. Herr Jesu Christ, dich zu uns wend’.

O. 59. N. xv. 99. B.G. xxv. (2) 48. P. v. 28. B.H. vii. 30.

M. 60. N. xviii. 50. B.G. xl. 30. P. v. 28. B.H. viii. 94.

E. 61. N. xvii. 26. B.G. xxv. (2) 98. P. vi. 70. B.H. viii. 96.

P. vi. 107-8 (B.G. xxv. (2) 159, 162) prints two older readings; B.G. xxv. (2) 160 a third.

M. 62. N. xviii. 52. B.G. xl. 72. B.H. viii. 100.

33. Herzlich thut mich verlangen.

M. 63. N. xviii. 53. B.G. xl. 73. P. v. 30. B.H. viii. 100.

34. Heut’ triumphiret Gottes Sohn.

O. 64. N. xv. 94. B.G. xxv. (2) 46. P. v. 30. B.H. vii. 31.

35. Hilf Gott, dass mir’s gelinge.

O. 65. N. xv. 76. B.G. xxv. (2) 36. P. v. 32. B.H. vii. 32.

36. Ich hab’ mein Sach’ Gott heimgestellt.

M. 66. N. xviii. 54. B.G. xl. 26. P. vi. 74. B.H. viii. 102.

M. 67. N. xviii. 58. B.G. xl. 30, 152. B.H. viii. 106.

37. Ich ruf’ zu dir, Herr Jesu Christ.

O. 68. N. xv. 111. B.G. xxv. (2) 55. P. v. 33. B.H. vii. 34.

38, 39. In dich hab’ ich gehoffet, Herr.

O. 69. N. xv. 113. B.G. xxv. (2) 56. P. v. 35. B.H. vii. 36.

On an anonymous melody dating from 1560.

M. 70. N. xviii. 59. B.G. xl. 36. P. vi. 94. B.H. viii. 107.

On a melody by Seth Calvisius, 1581.

40. In dir ist Freude.

O. 71. N. xv. 45. B.G. xxv. (2) 20. P. v. 36. B.H. vii. 37.

41. In dulci jubilo.

O. 72. N. xv. 26. B.G. xxv. (2) 12. P. v. 38. B.H. vii. 40.

M. 73. N. xviii. 61. B.G. xl. 74. P. v. 103. B.H. viii. 109.

A so-called variant is in B.G. xl. 158.

Edition: current; Page: [7]

42. Jesu, meine Freude.

O. 74. N. xv. 31. B.G. xxv. (2) 14. P. v. 34. B.H. vii. 35.

M. 75. N. xviii. 64. B.G. xl. 38. P. vi. 78. B.H. viii. 111.

A variant text is in B.G. xl. 155 and P. vi. 110.

A fragment is in B.G. xl. 163 and P. v. 112.

43. Jesus Christus, unser Heiland, Der den Tod.

O. 76. N. xv. 81. B.G. xxv. (2) 39. P. v. 34. B.H. vii. 36.

44. Jesus Christus, unser Heiland, Der von uns.

C. 77. N. xvi. 74. B.G. iii. 234. P. vi. 82. B.H. viii. 116.

C. 78. N. xvi. 80. B.G. iii. 239. P. vi. 92. B.H. viii. 128.

E. 79. N. xvii. 74. B.G. xxv. (2) 136. P. vi. 87. B.H. viii. 122.

An older text is in B.G. xxv. (2) 188 and P. vi. 112.

E. 80. N. xvii. 79. B.G. xxv. (2) 140. P. vi. 90. B.H. viii. 126.

45. Jesus, meine Zuversicht.

M. 81. N. xviii. 69. B.G. xl. 74. P. v. 103. B.H. viii. 130.

46. Komm, Gott, Schopfer, heiliger Geist.

O. 82. N. xv. 97. B.G. xxv. (2) 47. P. vii. 86 (B). B.H. vii. 41.

An older text is in B.G. xxv. (2) 150 and P. vii. 86 (A).

E. 83. N. xvii. 82. B.G. xxv. (2) 142. P. vii. 2. B.H. ix. 2.

47. Komm, heiliger Geist, Herre Gott.

E. 84. N. xvii. 1. B.G. xxv. (2) 79. P. vii. 4. B.H. ix. 5.

An older text is in B.G. xxv. (2) 151 and P. vii. 86.

E. 85. N. xvii. 10. B.G. xxv. (2) 86. P. vii. 10. B.H. ix. 12.

An older text is in B.G. xxv. (2) 153 and P. vii. 88.

48. Kommst du nun, Jesu, vom Himmel herunter.

S. 86. N. xvi. 14. B.G. xxv. (2) 74. P. vii. 16. B.H. ix. 18.

49. Kyrie, Gott Vater in Ewigkeit.

C. 87. N. xvi. 28. B.G. iii. 184. P. vii. 18. B.H. ix. 26.

C. 88. N. xvi. 36. B.G. iii. 194. P. vii. 26. B.H. ix. 22.

Edition: current; Page: [8]

50. Liebster Jesu, wir sind hier.

O. 89. B.G. xxv. (2) 49. P. v. 109. B.H. vii. 42 (31).

O. 90. N. xv. 101. B.G. xxv. (2) 50. P. v. 40. B.H. vii. 42 (32).

M. 91. N. xviii. 70. B.G. xl. 76. P. v. 105. B.H. ix. 36.

M. 92. N. xviii. 71. B.G. xl. 77. P. v. 105. B.H. ix. 37.

M. 93. N. xviii. 72. B.G. xl. 25. P. v. 39. B.H. ix. 38 (part only).

51. Lob sei dem allmächtigen Gott.

O. 94. N. xv. 11. B.G. xxv. (2) 6. P. v. 40. B.H. vii. 42.

M. 95. N. xviii. 73. B.G. xl. 22. P. v. 41. B.H. ix. 38.

52. Lobt Gott, ihr Christen, alle gleich.

O. 96. N. xv. 29. B.G. xxv. (2) 13. P. v. 42. B.H. vii. 43.

M. 97. N. xviii. 74. B.G. xl. 78. P. v. 106. B.H. ix. 39.

A variant is in B.G. xl. 159.

53. Meine Seele erhebt den Herren.

S. 98. N. xvi. 8. B.G. xxv. (2) 70. P. vii. 33. B.H. ix. 44.

M. 99. N. xviii. 75. B.G. xl. 79. P. vii. 29. B.H. ix. 40.

54. Mit Fried’ und Freud’ ich fahr’ dahin.

O. 100. N. xv. 50. B.G. xxv. (2) 24. P. v. 42. B.H. vii. 44.

55. Nun danket alle Gott.

E. 101. N. xvii. 40. B.G. xxv. (2) 108. P. vii. 34. B.H. ix. 46.

56. Nun freut euch, lieben Christen g’mein.

M. 102. N. xviii. 80. B.G. xl. 84. P. vii. 36. B.H. ix. 50.

The movement bears the alternative title, “Es ist gewisslich an der Zeit.”

A variant is in B.G. xl. 160 and P. vii. 91.

57. Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland.

O. 103. N. xv. 3. B.G. xxv. (2) 3. P. v. 44. B.H. vii. 45.

E. 104. N. xvii. 46. B.G. xxv. (2) 114. P. vii. 38. B.H. ix. 52.

An older text is in B.G. xxv. (2) 172 and P. vii. 92.

E. 105. N. xvii. 49. B.G. xxv. (2) 116. P. vii. 40. B.H. ix. 55.

Two older texts are in B.G. xxv. (2) 174, 176, and P. vii. 93, 94.

E. 106. N. xvii. 52. B.G. xxv. (2) 118. P. vii. 42. B.H. ix. 58.

An older text is in B.G. xxv. (2) 178 and P. vii. 96.

M. 107. N. xviii. 83. B.G. xl. 16. P. v. 45. B.H. ix. 61.

Edition: current; Page: [9]

58. O Gott, du frommer Gott.

V. 108. N. xix. 44. B.G. xl. 114. P. v. 68. B.H. vii. 66.

59. O Lamm Gottes unschuldig.

O. 109. N. xv. 58. B.G. xxv. (2) 28. P. v. 46. B.H. vii. 46.

E. 110. N. xvii. 32. B.G. xxv. (2) 102. P. vii. 45. B.H. ix. 62.

An older text is in B.G. xxv. (2) 166 and P. vii. 97.

60. O Mensch, bewein’ dein’ Sünde gross.

O. 111. N. xv. 69. B.G. xxv. (2) 33. P. v. 48. B.H. vii. 48.

61. Puer natus in Bethlehem (ein Kind geborn zu Bethlehem).

O. 112. N. xv. 13. B.G. xxv. (2) 6. P. v. 50. B.H. vii. 50.

62. Schmücke dich, O liebe Seele.

E. 113. N. xvii. 22. B.G. xxv. (2) 95. P. vii. 50. B.H. ix. 68.

A movement of doubtful authenticity (attributed to G. A. Homilius) is in B.G. xl. 181.

63. Sei gegrüsset, Jesu gütig.

V. 114. N. xix. 55. B.G. xl. 122. P. v. 76. B.H. vii. 75.

64. Valet will ich dir geben.

M. 115. N. xix. 2. B.G. xl. 86. P. vii. 53. B.H. ix. 71.

An older text is in B.G. xl. 161 and P. vii. 100.

M. 116. N. xix. 7. B.G. xl. 90. P. vii. 56. B.H. ix. 76.

65. Vater unser im Himmelreich.

O. 117. N. xv. 105. B.G. xxv. (2) 52. P. v. 52. B.H. vii. 51.

C. 118. N. xvi. 53. B.G. iii. 217. P. vii. 60. B.H. ix. 82.

C. 119. N. xvi. 61. B.G. ii. 223. P. v. 51. B.H. ix. 88.

A variant reading is in P. v. 109.

M. 120. N. xix. 12. B.G. xl. 96. P. vii. 66. B.H. ix. 80.

Two doubtfully authentic movements are in B.G. xl. 183, 184. They are both attributed to Georg Böhm.

Edition: current; Page: [10]

66. Vom Himmel hoch da komm ich her.

O. 121. N. xv. 21. B.G. xxv. (2) 9. P. v. 53. B.H. vii. 52.

M. 122. N. xix. 14. B.G. xl. 19. P. vii. 67. B.H. ix. 88.

M. 123. N. xix. 16. B.G. xl. 17. P. vii. 68. B.H. ix. 90.

M. 124. N. xix. 19. B.G. xl. 97. P. v. 106. B.H. ix. 92.

A variant is in B.G. xl. 159.

V. 125. N. xix. 73. B.G. xl. 137. P. v. 92. B.H. vii. 92.

67. Vom Himmel kam der Engel Schaar.

O. 126. N. xv. 23. B.G. xxv. (2) 10. P. v. 54. B.H. vii. 52.

68. Von Gott will ich nicht lassen.

E. 127. N. xvii. 43. B.G. xxv. (2) 112. P. vii. 70. B.H. ix. 94.

An older text is in B.G. xxv. (2) 170 and P. vii. 102.

69. Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme.

S. 128. N. xvi. 1. B.G. xxv. (2) 63. P. vii. 72. B.H. ix. 96.

70. Wenn wir in höchsten Nöthen sein.

O. 129. N. xv. 115. B.G. xxv. (2) 57. P. v. 55. B.H. vii. 54.

E. 130. N. xvii. 85. B.G. xxv. (2) 145. P. vii. 74. B.H. ix. 98.

To the movement Bach gives the alternative title, “Vor deinen Thron tret’ ich.”

71. Wer nur den lieben Gott lässt walten.

O. 131. N. xv. 117. B.G. xxv. (2) 58. P. v. 57. B.H. vii. 55.

S. 132. N. xvi. 6. B.G. xxv. (2) 68. P. vii. 76. B.H. ix. 100.

M. 133. N. xix. 21. B.G. xl. 3. P. v. 56 (53). B.H. ix. 102.

M. 134. N. xix. 22. B.G. xl. 4. P. v. 56 (52). B.H. ix. 103.

A variant is in B.G. xl. 151 and P. v. 111.

72. Wie schön leuchtet der Morgenstern.

M. 135. N. xix. 23. B.G. xl. 99. B.H. ix. 103.

A fragment is in B.G. xl. 164.

73. Wir Christenleut’.

O. 136. N. xv. 36. B.G. xxv. (2) 16. P. v. 58. B.H. vii. 56.

M. 137. N. xix. 28. B.G. xl. 32. P. ix. 52. B.H. ix. 108.

Edition: current; Page: [11]

74. Wir danken dir, Herr Jesu Christ.

O. 138. N. xv. 73. B.G. xxv. (2) 35. P. v. 59. B.H. vii. 57.

75. Wir glauben all’ an einen Gott, Schöpfer.

C. 139. N. xvi. 49. B.G. iii. 212. P. vii. 78. B.H. ix. 110.

C. 140. N. xvi. 52. B.G. iii. 216. P. vii. 81. B.H. ix. 113.

A movement confidently attributed to Bach is in B.G. xl. 187 and P. ix. 40.

76. Wir glauben all’ an einen Gott, Vater.

M. 141. N. xix. 30. B.G. xl. 103. P. vii. 82. B.H. ix. 114.

77. Wo soll ich fliehen hin.

S. 142. N. xvi. 4. B.G. xxv. (2) 66. P. vii. 84. B.H. ix. 116.

This movement has the alternative title, “Auf meinen lieben Gott,” the more correct style of the melody.

M. 143. N. xix. 32. B.G. xl. 6. P. ix. 48. B.H. ix. 118.

A movement of doubtful authenticity is in B.G. xl. 170 and P. ix. 39.

In addition to the foregoing, B.G. xl contains an Appendix of doubtful or incomplete movements (see page 346 infra). They are as follows:

Ach Gott, vom Himmel sieh’ darein.

B.G. xl. 167 and P. ix. 44.

The basis of the movement appears to be Bach’s work Completed by another hand.

Ach, was soll ich Sünder machen.

B.G. xl. 189.

A set of Variations, youthful if genuine.

Aus der Tiefe rufe ich.

B.G. xl. 171 and P. ix. 54.

Possibly an early work.

Edition: current; Page: [12]

Gott der Vater wohn’ uns bei.

B.G. xl. 177, N. xiii. 153, and P. vi. 62.

A variant is in P. vi. 106. Spitta attributes the movement to Johann Gottfried Walther.

O Vater, allmachtiger Gott.

B.G. xl. 179.

Perhaps an early work.

Jesu Leiden, Pein und Tod.

A movement on the melody is in P. ix. 52.

The Texts

Towards the end of his life Bach published the Catechism Chorals, Prelude and Fugue in E flat, and four Duetti, in Part III of the Clavierübung; the six Schubler Chorals: the Art of Fugue; the Musical Offering; and the Variations on “Vom Himmel hoch da komm ich her.” The rest of his Organ works remained in ms. When he died, in 1750, presumably they were intact. To-day only about one-third of his Organ music survives in his handwriting. The remainder has been printed from copies made by his pupils and others.

Bach’s Autographs of the Orgelbuchlein and the Eighteen Chorals are in the Konigliche Bibliothek, Berlin. The Schübler and Clavierübung Chorals and “Vom Himmel” Variations were in print before his death. It is therefore in regard to the miscellaneous or ungrouped Choral movements only that dubiety exists regarding the source of the published texts.

Edition: current; Page: [13]

Bach’s Organ Chorals were first edited by Friedrich Conrad Griepenkerl and Ferdinand Roitzsch for C. F. Peters, of Leipzig, who included them in his Edition of Bach’s Organ Works (vols. v, vi, vii, ix) in 1846-47-81. In 1893 Ernst Naumann edited a larger collection of them for the Bachgesellschaft (Jahrgang xl). Nine years later (1902) the same editor included most of them in Breitkopf and Haertel’s Edition. To the contents of the latter collection the Novello Edition (1916) makes no addition.

B.G. xl contains 52 miscellaneous (ungrouped) Preludes, 4 sets of Variations or Partite, 13 Variant texts or fragments, and 13 movements of doubtful authenticity, a total of 82 numbers. In the Peters Edition Griepenkerl already had printed 62 of them. Breitkopf and Haertel included 56 of them in their Edition. The Novello Edition contains the same number.

Of the 82 numbers printed in B.G. xl only four are in Bach’s Autograph: “Wer nur den lieben Gott lässt walten” (N. xix. 22), “Wie schön leuchtet der Morgenstern” (N. xix. 23), a fragment on the latter melody (B.G. xl. 164), and the “Vom Himmel hoch” Variations. The remaining seventy-eight compositions come to us through mss. written by other hands than Bach’s.

Edition: current; Page: [14]

By far the greater number of the mss. of Bach’s miscellaneous Organ works are in public institutions. The richest in mss. is the Konigliche Bibliothek, Berlin, which, since Griepenkerl prepared the Peters Edition, has absorbed a good deal of the material then in private hands. The Amalienbibliothek (Princess Amalia Library) in the Joachimsthal Gymnasium, Berlin; Mozartstiftung (Mozart Institution), Frankfort a. Main; Stadtbibliothek (Municipal Library), Leipzig; and the Universitätsbibliothek (University Library), Königsberg, also contain valuable collections of Bach mss.

In the Königliche Bibliothek are Bach’s Autographs of the Orgelbüchlein, Anna Magdalena’s Clavierbüchlein (1722), Notenbuch (1725), W. F. Bach’s Clavierbüchlein (1720), the “Vom Himmel hoch” Variations, and the Eighteen “Great” Preludes. It possesses also the collection of Count Voss of Berlin, who purchased from Bach’s eldest son, Wilhelm Friedemann Bach, a large number of his father’s mss.; the collection of Rudolf Westphal, a well-known writer on Bach; Professor Fischhof’s Bequest; an important collection made by Johann Nikolaus Forkel (1749-1818), Director of Music in the University of Göttingen, author of the first Edition: current; Page: [15] “Life” of Bach (1802); the “Sammelbuch” or “Sammelband” of Johann Ludwig Krebs (b. 1713), a student at the Leipzig Thomasschule under Bach from 1726 to 1735; a collection of Bach’s Organ compositions made by his last pupil, Johann Christian Kittel, organist at Erfurt (d. 1809), in a copy made by Herr Grasnick; copies of Bach’s Organ works made by Johann Peter Kellner, a pupil of Bach’s contemporary Johann Schmidt.

The Amalienbibliothek of Bach’s works, made by Princess Anna Amalia, sister of Frederick the Great, passed, after her death in 1787, into the possession of the Joachimsthal Gymnasium, Berlin. It contains a collection of 24 Choralvorspiele of Bach’s, made by Johann Philipp Kirnberger, who was born at Saalfeld in Thuringia in 1721, was Bach’s pupil at Leipzig from 1739-41, and eventually became Court musician to Princess Amalia of Prussia.

In the Mozartstiftung at Frankfort a. Main is the Schelble collection of “140 variirte Choräle von Joh. Edition: current; Page: [16] Sebastian Bach,” among which are many spurious movements. In 1846 it was in the possession of Herr Gleichauf. It was made by Johann Nepomuk Schelble (1789-1837), founder of the Frankfort Caecilienverein and one of the earliest Bach conductors.

The Leipzig Stadtbibliothek contains the Bequest of Carl Ferdinand Becker (1804-77), editor of the Choralgesänge and Professor of the Organ in the Leipzig Conservatorium.

In the Königsberg Universitätsbibliothek is a collection of Organ Chorals made by Johann Gottfried Walther (1684-1748), Bach’s contemporary at Weimar; and also the Gotthold Bequest.

Of private collections the most important is that of Herr Kämmersinger Joseph Hauser, of Carlsruhe. It was largely used by Griepenkerl in 1846, when it was in the possession of the singer Franz Hauser (1794-1870), a friend of Mendelssohn and an avid Bach collector. Included in the collection is a volume of “50 variirte und fugirte Choräle” in the handwriting of Johann Christoph Oley, organist at Aschersleben (d. 1789), and a ms. “Der anfahende Organist” in the handwriting of Herr Dröbs, a pupil of J. C. Kittel, which contains Organ movements by Bach.

Edition: current; Page: [17]

Philipp Spitta, Bach’s biographer, possessed a large collection of Bach mss. which he placed at the disposal of the Bachgesellschaft in 1893. It contained the collection of Friedrich Wilhelm Rust, of Dresden (1739-96), grandfather of the prolific editor of the Bachgesellschaft’s volumes; a collection of Organ movements made by Johann Gottfried Walther of Weimar, at one time in the possession of Herr Frankenberger, Director of Music at Sondershausen; a ms. “Verschiedene variirte Choräle von den besten Meistern älterer Zeit” made by Michael Gotthardt Fischer and dated 1793; a collection of Organ Chorals made by Bach’s uncle Johann Christoph Bach, organist at Eisenach; and a collection of J. S. Bach’s “variirten und fugirten Chorälen vor 1 und 2 Claviere und Pedal,” made by Johann Gottfried Schicht (1753-1823), Cantor of St Thomas’, Leipzig (1810-23), through whose influence the Motetts were published by Breitkopf and Haertel in 1803.

Other collections drawn upon in 1846 and 1893 were those of the publishers Breitkopf and Haertel; S. W. Dehn (1799-1858), sometime Keeper of the Department of Music in the Königliche Bibliothek; and Christian Friedrich Schwenke (1767-1822), Edition: current; Page: [18] successor to Philipp Emmanuel Bach at Hamburg and an industrious Bach collector.

Finally must be mentioned an important ms. once in the possession of Bach’s first cousin, Andreas Bach (b. 1713), which contains fourteen of Sebastian’s Organ Preludes, including the Choral “Göttes Sohn ist kommen” (N. xviii. 42).

In the following pages the derivation of the miscellaneous Preludes from the ms. sources named in this section is indicated.

The “Orgelbüchlein”

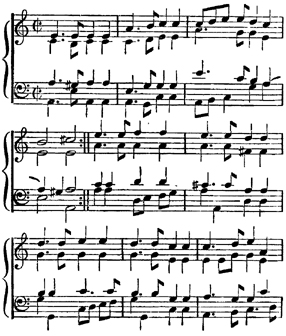

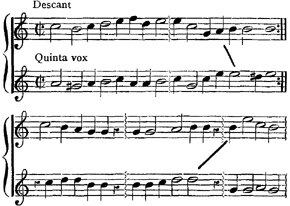

The Autograph of the Orgelbüchlein is in the Royal Library, Berlin. It is a small quarto of ninety-two sheets bound in paper boards, with leather back and corners, and bears the following title:

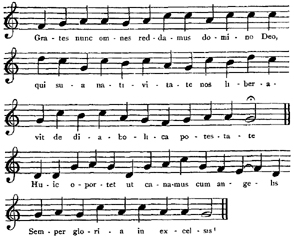

“Orgel-Büchlein Worinne einem anfahenden Organisten Anleitung gegeben wird, auff allerhand Arth einen Choral durchzufuhren, anbey auch sich im Pedal studio zu habilitiren, indem in solchen darinne befindlichen Choralen das Pedal gantz obligat tractiret wird.

- Dem Höchsten Gott allein zu Ehren,

- Dem Nechsten, draus sich zu belehren.

Autore Joanne Sebast. Bach p.t. Capellae Magistro S.P.R. Anhaltini-Cotheniensis.”

“A Little Organ Book, wherein the beginner may learn to perform Chorals of every kind and also acquire skill in the Edition: current; Page: [19] use of the Pedal, which is treated uniformly obbligato throughout.

- To God alone the praise be given

- For what’s herein to man’s use written.

Composed by Johann Sebast. Bach, pro tempore Capellmeister to His Serene Highness the Prince of Anhalt-Cöthen.”

According to the title-page, the Autograph was written at a time when Bach could describe himself as “pro tempore” in the service of Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Cöthen. His appointment to Cöthen was dated August 1, 1717, though he did not enter upon his duties until Christmas 1717. To that date he held the positions of Concertmeister and Court Organist at Weimar, where the death of the Capellmeister, Johann Samuel Drese, in 1716, had opened the prospect of obtaining that vacant post. When it was given to Drese’s son, Bach resolved to push his fortunes elsewhere, and, still bound to Weimar, accepted the Cöthen post in the summer of 1717. A petition for release from his Weimar duties was rejected. On November 6, 1717, he was placed under arrest “for obstinately insisting that his resignation should be accepted at once,” and remained in confinement for a month. He was not released until December 2, 1717, when he was permitted at length to resign his Weimar appointments.

Edition: current; Page: [20]

“As may be seen by the title-page,” writes Spitta, the Orgelbüchlein was “written at Cöthen.” The conclusion has been adopted by later writers and is accepted in the Novello Edition. It does not survive examination, however. Bach describes himself on the title-page as “pro tempore” in the service of Cöthen. Spitta explains the phrase as Bach’s manner of stating the fact, that though the Autograph was written at Cöthen, its contents had been composed at Weimar. But, surely, if that was Bach’s intention, it would have been more natural to state on the title-page (which, after all, was not written for publication) the earlier position he had since vacated. In other words, writing at Cöthen, as Spitta supposes, we should expect Bach to call himself “sometime Concertmeister to the Duke of Saxe-Weimar.”

If Spitta’s conclusion is discarded and the Autograph’s construction at Weimar is assumed, the puzzling phrase “pro tempore” falls in smoothly with the facts known to us. Between August 1 and December 2, 1717, Bach was by appointment Capellmeister to His Highness of Anhalt-Cöthen. But as his Weimar master refused to release him from service and even put him in prison for begging his resignation, Bach might reasonably describe as “pro tempore” an appointment which seemed little Edition: current; Page: [21] likely to become permanent. The conclusion may be stated with confidence, that the Autograph of the Orgelbüchlein was written at Weimar between August 1 and December 2, 1717.

It is possible to be more precise. As will be shown, the scheme of the Orgelbüchlein can have been in Bach’s mind since the autumn of 1715, but can hardly have been formed earlier. As to three-quarters of its programme the Orgelbuchlein is incomplete, and most of it was of little practical use to a Church organist. The scheme of the work, and Bach’s complete neglect of it in after years, support the conclusion that it was undertaken in a period of leisure and under an immediate impulse of enthusiasm. We are drawn, therefore, to search for a period of exceptional leisure in which Bach was free to sketch and partly write a lengthy work which in after years he never attempted to complete. Such a period presented itself during his incarceration at Weimar in November 1717, and during those weeks, it may be concluded, the Autograph was written.

But the date of the Autograph does not consequently determine the year in which all its forty-six completed movements were composed. Rust’s conclusion, in the B.G. Edition of the Orgelbüchlein, that they cannot have been composed earlier than Edition: current; Page: [22] the Cöthen period (1718-23) is already disproved. Spitta gives convincing grounds for the conclusion that they were not composed at Cöthen, where Bach had neither an adequate instrument nor duties as an organist, but at Weimar (1708-17), where both incentives existed. For he demonstrates clearly that the Autograph is not the earliest text of the movements it contains. Felix Mendelssohn possessed a ms. in Bach’s hand which contained twenty-six, and probably thirty-eight, of its forty-six completed movements. Indeed, Spitta makes out a strong case for the belief that the Mendelssohn ms. itself is a transcript of a still earlier text. It must therefore be concluded that the completed movements of the Orgelbüchlein were composed during Bach’s residence at Weimar, 1708-17, between his twenty-third and thirty-third years, and assumed their final shape in the Autograph written in November 1717.

Other than the Autograph, no complete copy of the Orgelbüchlein exists. But of its separate movements so large a number of mss. is found as to testify to their vogue among Bach’s pupils and contemporaries.

The fullest collection of them, after the Autograph, is in Kirnberger’s hand; in 1878 it was in the possession of Professor Wagener of Marburg, whose Edition: current; Page: [23] collection is in the Royal Library, Berlin. The collection contains all the completed (forty-six) movements except the first “Liebster Jesu, wir sind hier” and “Komm, Gott, Schöpfer, heiliger Geist.”

A smaller collection, revised by Bach himself, which contains “Gottes Sohn ist kommen,” “Christ lag in Todesbanden,” “Vater unser im Himmelreich,” “Ich ruf’ zu dir, Herr Jesu Christ,” “Wenn wir in höchsten Nöthen sein,” and “Ach wie nichtig, ach wie flüchtig,” was in 1878 in the possession of Wilhelm Rust, who acquired it from his grandfather, F. W. Rust.

Copies of six movements, “Herr Christ, der ein’ge Gottes-Sohn,” “O Mensch, bewein’ dein’ Sünde gross,” “Durch Adams Fall ist ganz verderbt,” “Es ist das Heil uns kommen her,” “Ich ruf’ zu dir, Herr Jesu Christ,” and “Wer nur den lieben Gott lässt walten,” originally belonging to Bach’s pupil Krebs, were in the possession of Court Organist Reichardt in 1846 and of Herr Ferdinand Roitzsch of Leipzig in 1878.

The Royal Library, Berlin, possesses copies of eight of the movements in the handwriting of Johann Gottfried Walther, Organist of the Town Church at Weimar during Bach’s residence there: “Lob sei dem allmächtigen Gott,” “Gelobet seist du, Jesu Christ,” “Vom Himmel hoch da komm ich her,” “Jesu, meine Freude,” “Das alte Jahr vergangen Edition: current; Page: [24] ist,” “Mit Fried’ und Freud’ ich fahr’ dahin,” “Herr Gott, nun schleuss den Himmel auf,” and “Heut’ triumphiret Gottes Sohn.”

MSS. of “Herr Christ, der ein’ge Gottes-Sohn” and “Es ist das Heil uns kommen her” are in a collection of Choral arrangements made by Walther of Weimar, in the possession (1878) of Herr Frankenberger, Director of Music at Sondershausen.

Twenty-eight of the Preludes, in the handwriting of Johann Christoph Oley, organist at Aschersleben (d. 1789), are in the Hauser Collection: “Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland,” “Gottes Sohn ist kommen,” “Herr Christ, der ein’ge Gottes-Sohn,” “Lob sei dem allmächtigen Gott,” “Puer natus in Bethlehem,” “Gelobet seist du, Jesu Christ,” “Der Tag, der ist so freudenreich,” “Vom Himmel hoch da komm ich her,” “In dulci jubilo,” “Lobt Gott, ihr Christen, alle gleich,” “Jesu, meine Freude,” “Christum wir sollen loben schon,” “Wir Christenleut’,” “In dir ist Freude,” “Mit Fried’ und Freud’ ich fahr’ dahin,” “Christe, du Lamm Gottes,” “Christus, der uns selig macht,” “O Mensch, bewein’ dein’ Sünde gross,” “Wir danken dir, Herr Jesu Christ,” “Hilf Gott, dass mir’s gelinge,” “Christ ist erstanden,” “Erstanden ist der heil’ge Christ,” “Komm, Gott, Schöpfer, heiliger Geist,” “Herr Jesu Christ, dich zu uns wend’,” “In dich hab’ ich gehoffet, Herr,” “Wenn wir in höchsten Nöthen sein,” “Alle Menschen Edition: current; Page: [25] müssen sterben,” and “Ach wie nichtig, ach wie flüchtig.”

An old ms. of twelve of the Preludes is in the University Library, Königsberg: “Herr Christ, der ein’ge Gottes-Sohn,” “Lob sei dem allmächtigen Gott,” “Gelobet seist du, Jesu Christ,” “Lobt Gott, ihr Christen, alle gleich,” “Jesu, meine Freude,” “Wir Christenleut’,” “Christe, du Lamm Gottes,” “Erschienen ist der herrliche Tag,” “Liebster Jesu, wir sind hier” (distinctius), “Ich ruf’ zu dir, Herr Jesu Christ,” “In dich hab’ ich gehoffet, Herr,” and “Alle Menschen müssen sterben.”

Griepenkerl mentions (1846) other copies by Dröbs, Oley, and Schelble.

Hence, apart from the Mendelssohn Autograph and Kirnberger’s ms., the only Preludes in the Orgelbüchlein not found in closely contemporary texts are “Da Jesus an dem Kreuze stund,” “Dies sind die heil’gen zehn Gebot’,” “Helft mir Gott’s Güte preisen,” “Jesus Christus, unser Heiland” (both), “O Lamm Gottes unschuldig,” and “Vom Himmel kam der Engel Schaar.”

Mendelssohn’s ms. contained twenty-six of the Preludes: “Das alte Jahr vergangen ist,” “In dir ist Freude,” “Mit Fried’ und Freud’ ich fahr’ dahin,” “Christe, du Lamm Gottes,” “O Lamm Gottes unschuldig,” “Da Jesus an dem Kreuze stund,” “O Mensch, bewein’ dein’ Sünde gross,” “Christus, Edition: current; Page: [26] der uns selig macht,” “Wir danken dir, Herr Jesu Christ,” “Hilf Gott, dass mir’s gelinge,” “Herr Gott, nun schleuss den Himmel auf,” “Christ lag in Todesbanden,” “Jesus Christus, unser Heiland,” “Christ ist erstanden,” “Erstanden ist der heil’ge Christ,” “Heut’ triumphiret Gottes Sohn,” “Erschienen ist der herrliche Tag,” “Es ist das Heil uns kommen her,” “Ich ruf’ zu dir, Herr Jesu Christ,” “In dich hab’ ich gehoffet, Herr” (alio modo), “Liebster Jesu, wir sind hier” (distinctius), “Dies sind die heil’gen zehn Gebot’,” “Vater unser im Himmelreich,” “Durch Adams Fall ist ganz verderbt,” “Komm, Gott, Schöpfer, heiliger Geist,” and “Herr Jesu Christ, dich zu uns wend’.” The last six movements Mendelssohn detached (three leaves) from the ms. and gave to his wife and Madame Clara Schumann. In 1880 the first two of the three leaves were in the possession of the wife of Professor Wach, Leipzig. The last was in that year in Madame Schumann’s keeping.

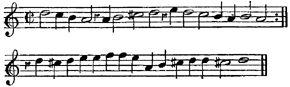

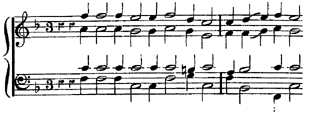

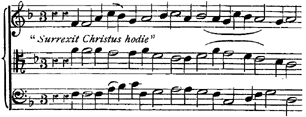

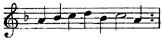

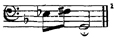

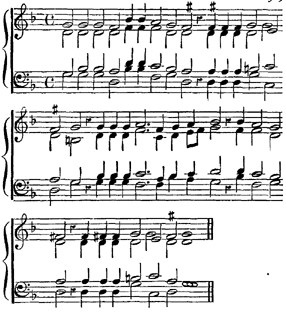

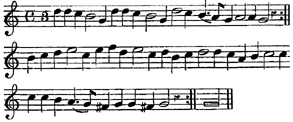

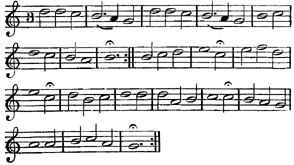

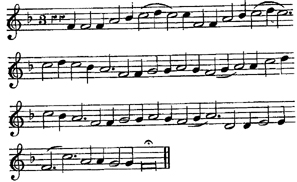

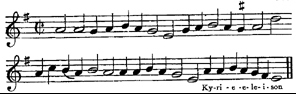

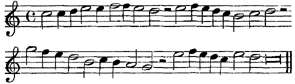

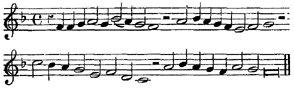

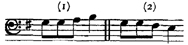

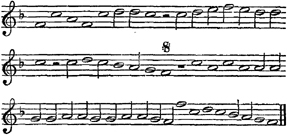

The ninety-two sheets of the Autograph were planned by Bach to contain 164 movements upon the melodies of 161 hymns; three hymns (Nos. 50-1, 97-8, 130-1) being represented by two movements in each case. Of the 164 projected movements only forty-six were written, two of them (Nos. 50-1) to the same melody (“Liebster Jesu, wir sind hier”). Edition: current; Page: [27] A fragment (two bars) of a forty-seventh movement, upon Johann Rist’s hymn, “O Traurigkeit, O Herzeleid,” was inserted:

The pages of the Autograph, other than those which contain the completed movements, are merely inscribed with the names of the hymns whose melodies Bach proposed to place upon them. Hence, the Orgelbüchlein contains forty-six Preludes and the titles of 118 unwritten ones. Why did Bach fail to complete a work conceived, as the title-page bears witness, in so lofty a spirit? Schweitzer suggests that the unused tunes lack the opportunities for poetic and pictorial expression that Bach required. If so, it is strange that 116 of the 161 hymns selected by Bach himself should be of that character. In fact, as Mr Newman points out in the Preface to the Novello Edition, Schweitzer’s hypothesis is not sound. Many of the unused tunes in the Orgelbuchlein are as capable of poetic Edition: current; Page: [28] and pictorial treatment as those Bach actually used there. Moreover elsewhere he has given some of them precisely the expression of which Schweitzer assumes them to be incapable.

The true reason for Bach’s failure to complete the Orgelbüchlein is found in the character of that work. Whatever may have been the circumstances that moved him to plan it and partially to write it, no practical incentive to its completion can be discovered. If, as has been asserted, Bach designed it as an exercise for his youthful son Friedemann, its forty-six completed movements were at least adequate as an Organ “tutor.” As a Church organist, the completed portion of it alone was of practical use to Bach himself. To establish the statement it is necessary to examine the contents of the Autograph.

When Griepenkerl edited the Orgelbüchlein in 1846 he suppressed all reference to the movements Bach projected but did not write, and—a more serious fault—printed the completed movements in alphabetical order, alleging, with consummate audacity, that “Bach himself attached no value to the order of succession”! On the contrary, Bach wrote the hymns into the Autograph in accordance with a carefully thought-out programme, which, however, he left concealed. The order in which the hymns appear in the Autograph is the only Edition: current; Page: [29] clue to it. In 1878 Rust pointed out, in the Preface to the Bachgesellschaft’s Edition, that “the Chorals of the Orgelbüchlein are in the order of the Church’s year.” But Rust’s analysis probed no deeper than the early movements and is inaccurate for the rest.

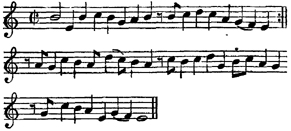

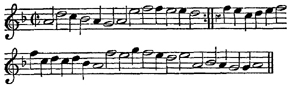

In the Musical Times of January 1917 the present writer exposed for the first time the complete scheme Bach had in mind in the Orgelbüchlein. He was able later to point out that Bach modelled it upon a Hymn-book issued in November 1715 for the neighbouring duchy of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg, edited by Christian Friedrich Witt (d. 1716), Capellmeister at Gotha. It bears the title:

“Psalmodia sacra, Oder: Andächtige und schöne Gesänge, So wohl des Sel. Lutheri, als anderer Geistreichen Manner, Auf Hochfl. gnädigste Verordnung, In dem Furstenthum Gotha und Altenburg, auf nachfolgende Art zu singen und zu spielen. Nebst einer Vorrede und Nachricht. Gotha, Verlegts Christoph Reyher, 1715.”

A copy of the book in the British Museum has another title (Neues Cantional: Gotha and Leipzig, 1715), but its contents are identical with the Gotha publication.

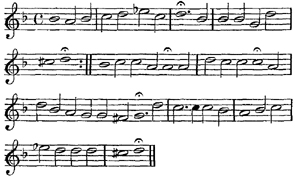

A collation of the Autograph and Witt’s Hymn-book shows that the latter provided Bach with 159 of the 161 hymns the Orgelbüchlein names. Nos. 6 Edition: current; Page: [30] and 83 of the Orgelbuchlein are not in Witt. Whence Bach took them cannot be stated and is immaterial; both were accessible in other collections. The Orgelbuchlein, in fact, is a condensed Hymnary and, for convenience, may be divided into two Parts. The first, and shorter, Part follows the seasons and festivals of the Church’s year, with one apparent omission. The second Part, almost wholly incomplete, contains hymns arranged in groups that conform to the divisions customary in Hymn-books of Bach’s period. Part I was planned to contain sixty Preludes, of which thirty-six were composed. Part II was designed to include one hundred and four Preludes, of which only ten were written. Five of its eleven groups contain not a single completed movement; one contains three; two contain two apiece; three contain one apiece.

The complete scheme of the Orgelbüchlein is set out hereunder, with notes upon the hymns and melodies Bach proposed to use. The hymns are named in the order in which Bach wrote them into the Autograph, and are grouped under the seasons or headings he intended them to illustrate but neglected to indicate. In order to show the close correspondence between the Orgelbüchlein and Witt’s Hymn-book, the latter’s group-headings are printed alongside those supplied to Bach’s scheme, the figures in brackets stating the numbers of the Edition: current; Page: [31] hymns in Witt’s corresponding group and revealing the extent to which Bach drew upon them. Similarly the numerical order of the hymns in the Orgelbüchlein is annotated by an indication of their position in Witt’s book. Titles in capitals indicate the forty-six completed movements of the Orgelbüchlein. Unless the contrary is stated, Witt’s and Bach’s tunes are identical.

Part I.: CHURCH SEASONS AND FESTIVALS.

* Bach uses the melody elsewhere in his concerted Church music or Organ works.

† A four-part setting of the melody is among the Choralgesange.

Advent Advents-Lieder (3-17).

*1 (4) Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland.

*†2 (5) Gottes Sohn ist kommen, or, Gott, durch deine Güte. (In Canone all’ Ottava, a 2 Clav. e Pedale.)

*3 (17) Herr Christ, der ein’ge Gottes-Sohn, or, Herr Gott nun sei gepreiset.

*4 (15) Lob sei dem allmächtigen Gott.

In Witt the hymn is set to the tune of No. 9 infra.

The Advent section calls for no comment. Bach selects from Witt four of his fifteen hymns on the season, altering the order of one, No. 4 (15), in order to end upon a note of joy in the approaching Edition: current; Page: [32] Incarnation. The other hymns invoke the coming Saviour.

Christmas Auf Weynachten (18-53).

*5 (35) Puer natus in Bethlehem.

6 Lob sei Gott in des Himmels Thron.

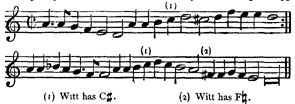

The hymn is not in Witt. It is by Michael Sachse (1542-1618) and was sung to the tune “Gelobet seist du, Jesu Christ.” As Bach treats that tune in No. 7 infra, it is to be inferred that he had in mind here the melody proper to the hymn, by J. Michael Altenburg, first printed in 1623 (Zahn, No. 1748).

*†7 (19) Gelobet seist du, Jesu Christ (a 2 Clav. e Pedale).

*†8 (20) Der Tag, der ist so freudenreich (a 2 Clav. e Pedale).

*9 (21) Vom Himmel hoch da komm ich her.

*10 (22) Vom Himmel kam der Engel Schaar (a 2 Clav. e Pedale).

*†11 (36) In dulci jubilo (Canone doppio all’ Ottava a 2 Clav. e Pedale).

*†12 (32) Lobt Gott, ihr Christen, allzugleich.

*†13 (337) Jesu, meine Freude.

*14 (34) Christum wir sollen loben schon (Corale in Alto).

*15 (33) Wir Christenleut’.

Bach arranges the Christmas hymns in an order different from Witt’s. The result is to transform a haphazard series of tunes into a Christmas Mystery. No. 5 announces the Incarnation and describes the homage of the Wise Men. Nos. 6 and 7 are acts of praise and thanksgiving for the Nativity. In No. 8 the Angels give the glad Edition: current; Page: [33] tidings to the shepherds. Nos. 9 and 10 picture the Manger at Bethlehem. In No. 11 we listen to the Angels’ carol there. The next three hymns are songs of thanksgiving; the second of them (No. 13), transferred from another section of Witt’s Hymn-book, being an act of intimate personal homage, very characteristic of Bach. The inversion of Witt’s order for the last two hymns is intentional. “Wir Christenleut’ ” summarizes the lesson of the Christmas season—he who stands steadfast on the fact of the Incarnation shall never be confounded. On that note Bach prefers to end.

New Year Auf das Neue Jahr (54-72).

*16 (56) Helft mir Gott’s Güte preisen.

†17 (57) Das alte Jahr vergangen ist (a 2 Clav. e Pedale).

18 (62) In dir ist Freude.

The three hymns follow Witt’s order. The first two look back upon the old year. The third is instinct with the hope and promise of the new one.

Purification of the B.V.M. Auf Lichtmess (78-83).

*†19 (80) Mit Fried’ und Freud’ ich fahr’ dahin.

20 (81) Herr Gott, nun schleuss den Himmel auf (a 2 Clav. e Pedale).

Bach omits, or appears to omit, the Epiphany (Witt, Nos. 73-77), which falls between the New Year and the Feast of the Purification. No. 19, however, is in modern use as an Epiphany hymn, Edition: current; Page: [34] and No. 20, which recalls the Song of Simeon, is not less appropriate. Probably Bach intended the two hymns to do duty for both contiguous festivals.

Passiontide Vom Leiden Christi (90-138).

*†21 (104) O Lamm Gottes unschuldig (Canone alla Quinta).

*22 (103) Christe, du Lamm Gottes (in Canone alla Duodecima a 2 Clav. e Pedale).

*†23 (95) Christus, der uns selig macht (in Canone all’ Ottava).

24 (113) Da Jesus an dem Kreuze stund.

*†25 (96) O Mensch, bewein’ dein’ Sunde gross (a 2 Clav. e Pedale).

26 (135) Wir danken dir, Herr Jesu Christ, dass du für uns gestorben bist.

†27 (94) Hilf Gott, dass mir’s gelinge (Canone alla Quinta a 2 Clav. e Pedale).

28 (124) O Jesu, wie ist dein’ Gestalt.

The hymn is attributed to Melchior Franck. It is in ten stanzas, addressed to the Feet (st. ii), Knees (st. iii), Hands (st. iv, v), Side (st. vi), Breast (st. vii), Heart (st. viii), and Face (st. ix) of Jesus. Witt sets it to the tune “Wie schön leuchtet der Morgenstern.” As Bach introduces that melody in No. 120 infra, it is probable that he intended to use the proper melody of Franck’s (?) hymn here. It was published, with the hymn, in 1627 and is by Franck himself (Zahn, No. 8360). Both hymn and melody are found in the Gotha Cantional of 1646, and therefore have a strong Saxon tradition.

†29 (127) O Traurigkeit, O Herzeleid.

The hymn, by Johann Rist, written for special use on Good Friday, is described as a “Klägliches Grab-Lied uber die trawrige Begräbnisse unseres Heylandes Jesu Edition: current; Page: [35] Christi.” In Witt the hymn is set to its own melody, published, with the hymn, in 1641. Bach intended to use it here, as the sketch of the opening bars in the Autograph shows. There is a four-part setting of it among the Choralgesänge, No. 288.

30 (290) Allein nach dir, Herr Jesu Christ, verlanget mich.

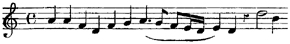

The hymn is by Nikolaus Selnecker. In Witt it is set to a melody probably by Witt himself (Zahn, No. 8544). Perhaps Bach intended to use it, but there are earlier tunes (Zahn, Nos. 8541-2).

†31 (129) O [Ach] wir armen Sunder.

The hymn, a Litany, is by Hermann Bonn (c. 1504-48). The melody to which it is set in Witt dates at least from the end of the fourteenth century, when it was sung to the hymn “Eya der grossen Liebe.” It is found in association with Bonn’s hymn in 1561 (Zahn, No. 8187c). There is a four-part setting of it among Bach’s Choralgesänge, No. 301.

*32 (108) Herzliebster Jesu, was hast du verbrochen.

The hymn is by Johann Heermann and occurs in the St Matthew Passion and St John Passion. It is set in Witt to Johann Cruger’s melody (1640), which Bach uses in the Passions, but not elsewhere.

33 (126) Nun giebt mein Jesus gute Nacht.

This long (21 stanzas) Good Friday hymn by Johann Rist does not appear to have a melody proper to itself. In Witt it is set to the melody of “Herr Jesu Christ, wahr Mensch und Gott” (Zahn, No. 340c), a tune which Bach has not used elsewhere. See No. 128 infra.

In the Passiontide section Bach entirely discards Witt’s order and follows the stages of the great tragedy in their sequence. The first three hymns call Edition: current; Page: [36] us to Calvary. No. 24 stations us before the Cross. No. 25 challenges mankind to own its guilt in Christ’s martyrdom. No. 26, in another mood, gives thanks for the approaching Atonement. In No. 27, a long ballad of the Passion, the death and sufferings of the Saviour are consummated. No. 28 is a passionate invocation of the pierced Hands, Feet, and Side. No. 29 is sung at the Saviour’s burial. Christ being dead, Bach hastens to utter (No. 30) a fervent song of faith, followed by two hymns of remorse and self-accusation. No. 33 leaves the Saviour sleeping in the Tomb. The section is a miniature of the greater Passion written twelve years later.

Easter Von der Auferstehung Jesu Christi (139-157).

*†34 (140) Christ lag in Todesbanden.

†35 (144) Jesus Christus, unser Heiland, der den.

*†36 (141) Christ ist erstanden.

†37 (143) Erstanden ist der heil’ge Christ.

*38 (146) Erschienen ist der herrliche Tag (a 2 Clav. e Pedale in Canone).

†39 (145) Heut’ triumphiret Gottes Sohn.

The Easter section closely follows Witt’s order. Bach begins it with introductory hymns (Nos. 34-36) which summon us to the festival. The last two hymns are songs of triumph, “Heut’ triumphiret” being placed out of Witt’s order so as to end on the thought of Death conquered. The centre of the section is held by “Erstanden ist der heil’ge Edition: current; Page: [37] Christ,” a dialogue between the Virgin Mary and the Angel at the Tomb, which states the circumstances of the Resurrection, the central thought of the festival.

Ascension Day Von der Himmelfahrt Jesu Christi (158-167).

40 (160) Gen Himmel aufgefahren ist.

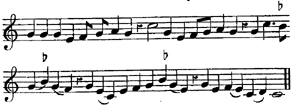

The hymn is a translation of the Latin “Coelos ascendit hodie.” It is set in Witt to a melody by Melchior Franck (1627) which is in very general use (Zahn, No. 189). There can be little doubt that Bach intended to introduce it here. The hymn is also sung to an older melody (Zahn, No. 187a), which dates from the middle of the sixteenth century.

†41 (165) Nun freut euch, Gottes Kinder, all.

The hymn is by Erasmus Alberus (d. 1553). It is set in Witt to a melody of which there is a four-part setting among the Choralgesänge, No. 260.

Whit Sunday Auf das heiliges Pfingst-Fest (168-184).

42 (169) Komm, heiliger Geist, erfüll’ die Herzen deiner Glaubigen.

Luther’s version of the antiphon “Veni Sancte Spiritus reple tuorum.” It is set in Witt to the old Latin melody (Zahn, No. 8594) which Bach, no doubt, intended to introduce here.

*43 (170) Komm, heiliger Geist, Herre Gott.

Another version, by Luther, of the antiphon “Veni Sancte Spiritus reple tuorum.” It is set in Witt to the old melody which Bach uses elsewhere in Cantatas 59, 172, 175, and a Motett; also in the Eighteen Chorals.

*†44 (171) Komm, Gott, Schöpfer, heiliger Geist.

*†45 (173) Nun bitten wir den heil’gen Geist.

One of the few vernacular pre-Reformation hymns, with stanzas added by Luther. The tune occurs in Edition: current; Page: [38] Cantatas 169 and 197, and there is another harmonization of it in the Choralgesange, No. 254.

†46 (172) Spiritus Sancti gratia, or, Des heil’gen Geistes reiche Gnad.

The hymn is a German version of the Latin “Spiritus Sancti gratia Apostolorum pectora implevit sua gratia, donans linguarum genera.” It is set in Witt to a melody by Melchior Vulpius (Zahn, No. 2601) published in 1609 and repeated in the Gotha Cantional of 1646. On the other hand, there exists a sixteenth century melody to the hymn (Zahn, No. 370a) which Johann H. Schein modernized in 1627 and of which a four-part setting is among Bach’s Choralgesänge, No. 63. Schein was one of Bach’s predecessors at Leipzig and the four-part setting may be presumed to have been written for one of the lost Leipzig Cantatas.

47 (174) O heil’ger Geist, du gottlich’s Feu’r.

An anonymous hymn, set in Witt to a melody by Melchior Vulpius (Zahn, No. 2027) published in 1609 and repeated in the Gotha Cantional of 1646.

48 (176) O heiliger Geist, O heiliger Gott.

The hymn, probably by Johann Niedling (1602-1668), is set in Witt to a melody (Zahn, No. 2016a) which dates from 1650. Witt may have taken it from Freylinghausen (1704), where it also occurs.

The Whitsuntide section closely follows Witt’s order and needs no exegesis.

Trinity (Before the Sermon) Vor der Predigt (240-241).

*†49 (240) Herr Jesu Christ, dich zu uns wend’.

*†50 (241) Liebster Jesu, wir sind hier (in Canone alla Quinta a 2 Clav. e Pedale).

*†51 (241) Liebster Jesu, wir sind hier (distinctius).

Trinity Auf Trinitatis (185-200).

†52 (185) Gott, der Vater, wohn’ uns bei.

The hymn is by Luther. It is set in Witt to the original Edition: current; Page: [39] melody, of which Bach has a four-part setting in the Choralgesange, No. 113.

*†53 (188) Allein Gott in der Höh’ sei Ehr’.

Nikolaus Decius’ version of the “Gloria in excelsis Deo.” Its melody occurs in Cantatas 85, 104, 112, and 128. There is a four-part setting of it among the Choralgesänge, No. 12.

†54 (189) Der du bist Drei in Einigkeit.

The hymn is by Luther. It is set in Witt to the melody “O lux beata trinitas,” of which there is a four-part setting in the Choralgesange, No. 61, where Bach follows Schein’s reconstruction of the melody.

The Trinity section contains six numbers, of which only the last three hymns are found in Witt’s Trinity group. Nos. 49 and 50 are taken by Bach from Witt’s “Vor der Predigt” (Before the Sermon) section. That Bach intended them for Trinity use is to be inferred from the irrelevance of a general “Before the Sermon” group of hymns between the Whitsuntide and Trinity sections. In regard to No. 49 it is not improbable that local use at Weimar attached it to Trinity, to whose season it is generally relevant. The hymn is attributed to a former Duke of Saxe-Weimar. Its fourth stanza is appropriate to the season:

- To God the Father, God the Son,

- And God the Spirit Three in One,

- Be honour, praise, and glory given

- By all on earth, and Saints in Heaven.

No. 50 acquires a Trinity significance through its second stanza:

Edition: current; Page: [40]

- All our knowledge, sense, and sight

- Lie in deepest darkness shrouded,

- Till Thy Spirit breaks our night

- With the beams of truth unclouded.

The strongest reason for believing that Bach intended both hymns to be attached to the Trinity group is in the fact that he copied into the Autograph two movements upon the second hymn, “Liebster Jesu, wir sind hier,” which differ so little textually that it is impossible to suppose his reason for duplicating the tune to have been a musical one. Witt, in fact, only offered two hymns, whereas Bach’s attention to symbolism moved him to pay separate homage to the three Persons of the Trinity. The regular Trinity hymns (Nos. 52-54) also are three in number.

St John the Baptist Am Tage Johannis des Täufers (201-4).

55 (201) Gelobet sei der Herr, der Gott Israel.

This version of the Benedictus is by Erasmus Alberus, and in Witt’s book is directed to be sung to the plainsong of the Magnificat. As Bach introduces that melody in the next movement it may be concluded that he did not propose to use it here also. The melody proper to the hymn is dated 1564 (Zahn, No. 5854).

Visitation of the B.V.M. Auf Mariä Heimsuchung (205-207).

*†56 (205) Meine Seel’ erhebt den Herren.

The Magnificat. Bach uses its melody (Tonus Peregrinus) in Cantata 10. There are two Organ movements upon it and two four-part settings in the Choralgesange, Nos. 120, 121.

Edition: current; Page: [41]

Bach omits the Annunciation. Six hymns for that festival are in Witt (Nos. 84-89).

St Michael the Archangel Auf Michaelis Tag (208-215).

*†57 (209) Herr Gott, dich loben alle wir.

The hymn is by Paul Eber. The melody was composed by Louis Bourgeois and was set originally to Psalm 134 (“Or sus, serviteurs du Seigneur”) in 1551. The hymn and melody occur in Cantata 130, and there are three four-part settings of the tune in the Choralgesange, Nos. 129, 130 (? J. S. B.), 132. It is familiar as the “Old Hundredth.”

†58 (208) Es steh’n vor Gottes Throne.

The hymn is by Ludwig Helmbold. It is set in Witt to a tune by Joachim von Burck (1541?-1610), published in 1594. There is a four-part setting of it among the Choralgesange, No. 93.

Feasts of the Apostles Auf der Apostel Tage (216-218).

*†59 (216) Herr Gott, dich loben wir.

Luther’s version of the Te Deum and its melody are in Cantatas 16, 119, 120, 190. There is an Organ movement upon it and a four-part setting in the Choralgesange, No. 133.

*60 (217) O Herre Gott, dein göttlich Wort.

Anark of Wildenfels’ (?) hymn is set in Witt to its original melody. Bach uses it in Cantata 184.

Part II.: THE CHRISTIAN LIFE.

The Ten Commandments Von den zehen Geboten (221-225).

*†61 (222) Dies sind die heil’gen zehen Gebot’.

62 (221) Mensch, willst du leben seliglich.

The hymn is by Luther. In Witt it is directed to be sung to the melody “Dies sind die heil’gen zehn Gebot’.” Edition: current; Page: [42] As Bach uses the latter in No. 61 supra, presumably he had in mind the proper (1524) melody of the hymn (Zahn, No. 1956) for use here.

63 (219) Herr Gott, erhalt’ uns fur und fur.

Ludwig Helmbold’s hymn is set in Witt to its proper melody, by Joachim von Burck (Zahn, No. 443), published in 1594. The hymn appears to have no other melody.

The Creed Vom Glauben (226-229).

*64 (228) Wir glauben all’ an einen Gott, Vater.

The hymn is by Tobias Clausnitzer. It is set in Witt to the melody which Bach uses in N. xix. 30.

Prayer Vom Gebeth (230-239).

*†65 (232) Vater unser im Himmelreich.

Holy Baptism Von der Tauffe (243-245).

*†66 (243) Christ, unser Herr, zum Jordan kam.

The melody of Luther’s hymn occurs in Cantatas 7, 176, and the Organ works. There is also a four-part setting of it among the Choralgesänge, No. 43.

Nos. 61 to 66 form a group of Catechism hymns. Bach and Witt (Nos. 219-45), whom he follows, treat the heads of the Catechism in the customary order. Bach interchanges Nos. 61 and 62, using the former, as being more definitive, to introduce the Ten Commandments group.

Penitence and amendment Buss-Lieder (246-270).

*67 (261) Aus tiefer Noth schrei ich zu dir.

The hymn is by Luther. Its familiar melody also is probably by him. Bach uses it in Cantata 38 as well as in the Clavierübung. Witt uses another (1525) tune (Zahn, No. 4438a).

Edition: current; Page: [43]

*†68 (258) Erbarm’ dich mein, O Herre Gott.

The hymn is by Erhart Hegenwalt. The melody, probably by Johann Walther, was published with the hymn in 1524. Bach uses it in the miscellaneous Preludes. There is a four-part setting of it among the Choralgesange, No. 78.

*†69 (286) Jesu, der du meine Seele.

Johann Rist’s hymn is set in Witt to a melody published in 1662 to Harsdorffer’s “Wachet doch, erwacht, ihr Schlafer.” Bach uses it in Cantatas 78 and 105, and there are three four-part settings of it among the Choralgesange, No. 185-187.

*†70 (280) Allein zu dir, Herr Jesu Christ.

The hymn is by Johannes Schneesing. The melody also is attributed to him. It occurs in Cantata 33. There is a four-part setting of it among the Choralgesange, No. 15.

*†71 (265) Ach Gott und Herr.

The authorship of the hymn is disputed. The melody is used by Bach in Cantata 48 and among the miscellaneous Preludes. A four-part setting of it is among the Choralgesange, No. 3.

*†72 (283) Herr Jesu Christ, du höchstes Gut.

The hymn is by Bartholomaus Ringwaldt. The melody occurs in a variety of forms, Witt’s being the Tenor of a four-part setting of the tune “Wenn mein Stundlein” (Zahn, Nos. 4484, 4486). Bach uses it in Cantatas 48, 113, 166, 168, and there is a four-part setting of it among the Choralgesange, No. 141.

*†73 (253) Ach Herr, mich armen Sünder.

The hymn is by Cyriacus Schneegass. Its tune is also known as “Herzlich thut mich verlangen.” Bach employs it in Cantatas 25, 135, 153, 159, 161 and the miscellaneous Preludes. There are two four-part settings of it among the Choralgesänge, Nos. 157, 158.

Edition: current; Page: [44]

*74 (282) Wo soll ich fliehen hin.

The hymn is by Johann Heermann. The melody Witt uses is perhaps by Caspar Stieler. Bach uses it in two Cantatas of the Weimar period, Nos. 163 and 199. The melody “Wo soll ich fliehen hin,” which he uses elsewhere, is more correctly styled “Auf meinen lieben Gott” (see No. 136 infra).

75 (267) Wir haben schwerlich.

The melody of this anonymous hymn is taken by Witt from a five-part setting in the Gotha Cantional of 1648 (Zahn, 2099). Bach has not made use of it elsewhere.

*76 (291) Durch Adams Fall ist ganz verderbt.

*77 (292) Es ist das Heil uns kommen her.

In the Penitential group Bach draws upon Witt’s corresponding section and his “Faith” and “Justication by Faith” hymns. He begins (Nos. 67, 68) with a cry of despair:

- Out of the depths I cry to Thee,

- Lord, hear me, I implore Thee;

and

- Behold, I was all born in sin,

- My mother conceived me therein.

He adds words of comfort; Johann Rist’s (No. 69)

- Jesu, Who, in sorrow dying,

- Didst deliverance bring to me;

and Schneesing’s (No. 70)

- Lord Jesus Christ, in Thee alone

- My only hope on earth I place.

But the mood of despair returns (No. 71):

- Alas! my God! my sins are great,

- My conscience doth upbraid me,

- And now I find in my sore strait

- No man hath power to aid me;

Edition: current; Page: [45]

and again (No. 72):

- Jesus, Thou Source of every good,

- Pure Fountain of Salvation,

- Behold me bowed beneath the load

- Of guilt and condemnation;

and again (No. 73):

- A sinner, Lord, I pray Thee,

- Recall Thy dread decree;

- Thy fearful wrath, O spare me,

- From judgment set me free.

There falls (No. 74) a ray of hope:

- My heavy load of sin

- To Thee, O Lord, I bring;

- .................................

- From out Thy Side love floweth,

- And saving grace bestoweth.

After a final (No. 75) act of contrition, the section ends with heartening comfort: Lazarus Spengler’s (No. 76)

- He that hopeth in God steadfastly

- Shall never be confounded;

and Paul Speratus’ (No. 77)

- Salvation hath come down to us

- Of freest grace and love.

It is characteristic of Bach’s temperament that the last two hymns, with their message of comfort, are the only completed movements in the section.

Holy Communion Vom Abendmahl des Herrn (308-333).

*†78 (320) Jesus Christus, unser Heiland, Der von uns.

The hymn is by Luther. The tune also is attributed to him. It occurs in four Organ Preludes, and there is a four-part setting of it among the Choralgesange, No. 206.

Edition: current; Page: [46]

†79 (324) Gott sei gelobet und gebenedeiet.

The hymn is by Luther, and the melody is based on pre-Reformation material. There is a four-part setting of it among the Choralgesange, No. 119.

80 (633) Der Herr ist mein getreuer Hirt.

The hymn is by Wolfgang Meusel. It is set in Witt to a melody (Zahn, No. 4432a) not used by Bach elsewhere. In the Cantatas he invariably sets the hymn to Decius’ “Allein Gott in der Höh’ sei Ehr’ ” (see No. 53 supra).

81 (319) Jetzt komm ich als ein armer Gast.

The hymn, whose first line also reads, “Ich komm jetzt als ein armer Gast,” is by Justus Sieber (1628-95). In Witt it is directed to be sung to the melody “Herr Jesu Christ, du höchstes Gut” (see No. 72 supra). Bach has not used the hymn’s proper melody (Zahn, No. 4646) elsewhere.

82 (322) O Jesu, du edle Gabe.

The hymn is by Johann Böttiger (1613-72). It is set in Witt to a melody (Zahn, No. 3892b) which Bach has not used elsewhere.

83 Wir danken dir, Herr Jesu Christ, Dass du das Lämmlein.

The hymn is by Nikolaus Selnecker. It is not in Witt. Bach has not used its melody (Zahn, No. 479 or 480) elsewhere.

*84 (317) Ich weiss ein Blumlein hubsch und fein.

The anonymous hymn is set in Witt to a melody used by Bach in Cantata 106, and also known as “Ich hab’ mein Sach’ Gott heimgestellt.”

*†85 (293) Nun freut euch, lieben Christen, g’mein.

Luther’s hymn has two melodies. Of the older (1524) there is a four-part setting among the Choralgesänge, No. 261. The second (1529 or 1535) occurs in the Christmas Oratorio, Cantata 70, the miscellaneous Preludes, and in a four-part setting among the Choralgesänge, Edition: current; Page: [47] No. 262. The second tune has been attributed to Luther, and for that reason perhaps Bach preferred it. Witt also uses it.

*†86 (384) Nun lob’, mein’ Seel’, den Herren.

The hymn is by Johann Graumann. The melody, probably composed by Johann Kugelmann, is used by Bach in Cantatas 17, 28, 29, 51, 167, Motett 1. There are four-part settings of it among the Choralgesange, No. 269, 270.

Of the nine hymns in the Holy Communion group only five (Nos. 78, 79, 81, 82, 84) are found in Witt’s corresponding section. The rest are drawn from other parts of Witt’s book or (No. 83) are introduced from outside it. Bach is working out a “programme” of his own. The section begins with Luther’s “Jesus Christus, unser Heiland,” which Bach used many years later for the Eucharistic hymn in the Clavierübung. It is an invitation to the Holy Table:

- Christ Jesus, our Redeemer born,

- Who from us did God’s anger turn,

- That we never should forget it,

- Gave He us His flesh to eat it.

- Who will draw near to that table

- Must take heed, all he is able.

- Who unworthy thither goes,

- Thence death, instead of life, he knows.

No. 79, Luther’s “Gott sei gelobet,” is a prayer that the communicant may worthily receive Christ’s Flesh and Blood.

Edition: current; Page: [48]

No. 80, transferred from another section of Witt’s book, brings the communicant to the Holy Table:

- The Lord He is my Shepherd true,

- My steps He safely guideth;

- With all good things in order due

- His bounty me provideth.

No. 81 is an act of devotion before receiving the Sacramental Food:

- Thy poor unworthy guest, O Lord,

- I place me at Thy Table.

No. 82 is an act of thanksgiving after communicating:

- From my sins Thy Blood hath cleansed me,

- From Hell’s flames Thy love hath snatched me.

No. 83 is a grateful invocation of the atoning Lamb of God.

In No. 84 the worshipper apostrophizes the rich gift vouchsafed to him.

The last two hymns (Nos. 85, 86), drawn from other parts of Witt’s book, end upon a note of thanksgiving.

The common weal Von denen drey Haupt-Standen (471-473).

87 (473) Wohl dem, der in Gottes Furcht steht.

The hymn is by Martin Luther. In Witt it is directed to be sung to the tune “Wo Gott zum Haus nicht giebt sein’ Gunst.” As that melody occurs in No. 88 infra Bach had in mind to introduce here, perhaps, an older tune (Zahn, No. 298) associated with Luther’s hymn. He has not used it elsewhere.

Edition: current; Page: [49]

†88 (472) Wo Gott zum Haus nicht giebt sein’ Gunst.

The hymn is attributed to Johann Kolross. The melody, which dates from 1535, belongs also to Luther’s “Wohl dem, der in Gottes Furcht steht.” A four-part setting of it is among the Choralgesange, No. 389.

The section does not need comment. Bach includes in it two of the three hymns allotted by Witt to “The Three Estates.”

Christian life and experience Vom Christlichen Leben und Wandel (514-597).

*89 (694) Was mein Gott will, das g’scheh’ allzeit.

Albrecht Margrave of Brandenburg-Culmbach’s hymn and the French melody associated with it occur in Cantatas 65, 72, 92, 103, 111, 144, and in the St Matthew Passion.

*90 (514) Kommt her zu mir, spricht Gottes Sohn.

The hymn is by Georg Gruenwald. Bach uses the melody in Cantatas 74, 86, 108.

*91 (299) Ich ruf’ zu dir, Herr Jesu Christ.

†92 (531) Weltlich Ehr’ und zeitlich Gut.

The hymn is by Michael Weisse. It is set in Witt to a melody (Zahn, No. 4977) which Bach has not used elsewhere. There is a four-part setting of the original melody of the hymn in the Choralgesange, No. 351.

*†93 (542) Von Gott will ich nicht lassen.

The melody of Ludwig Helmbold’s hymn occurs in Cantatas 11, 73, 107, and in the Organ Preludes. There are three four-part settings of it among the Choralgesange, Nos. 324-326.

†94 (525) Wer Gott vertraut.

The first stanza of the hymn is by Joachim Magdeburg. It is set in Witt to a version of the original (1572) melody found in Calvisius in 1597. There is a four-part setting of it among the Choralgesange, No. 366.

Edition: current; Page: [50]

95 (526) Wie’s Gott gefallt, so gefällt mir’s auch.

The hymn is by Ambrosius Blaurer (1492-1564). It is set in Witt to “Was mein Gott will, das g’scheh’ allzeit” (No. 89 supra). Its proper melody (Zahn, No. 7574) bears a likeness to the latter. Bach has not used it elsewhere.

*†96 (527) O Gott du frommer Gott.

The hymn is by Johann Heermann. It is set in Witt to an anonymous melody which Bach uses in Cantatas 24, 71, 164. There is a four-part setting of it among the Choralgesänge, No. 282. Elsewhere in the Cantatas Bach uses a second melody, and for the Partite a third.

Excepting Nos. 89 and 91, the hymns in the “Christian Life” section are taken from Witt’s corresponding group. Bach varies Witt’s order, but his own does not indicate a “programme.”

In time of trouble Vom Creutz und Verfolgung (598-658).

*97 (606) In dich hab’ ich gehoffet, Herr.

The hymn is by Adam Reissner. It is set in Witt to Calvisius’ melody, which Bach uses in Cantatas 52 and 106, the St Matthew Passion, the Christmas Oratorio, and the Organ Preludes.

98 (606) In dich hab’ich gehoffet, Herr (Alio modo).

Witt’s tune is that indicated in No. 97 supra.

99 (630) Mag ich Ungluck nicht widerstahn.

The melody (Zahn, No. 8113) of this anonymous hymn does not occur elsewhere in Bach.

*†100 (656) Wenn wir in hochsten Nöthen sein.

*†101 (601) An Wasserflussen Babylon.

The hymn and the melody are by Wolfgang Dachstein. Bach uses the melody elsewhere in the Organ Preludes, and there is a four-part setting of it among the Choralgesange, No. 23.

*†102 (638) Warum betrubst du dich, mein Herz.

The hymn is attributed to Hans Sachs. It is set in Edition: current; Page: [51] Witt to the ancient tune which Bach uses in Cantatas 47 and 138 and of which there are four-part settings in the Choralgesänge, Nos. 331, 332.

103 (639) Frisch auf, mein’ Seel’, verzage nicht.

The hymn is by Caspar Schmucker. Witt directs it to be sung to the tune “Was mein Gott will” (see No. 89 supra). Its proper melody is found in the Gotha Cantional of 1648 (Zahn, No. 7578). Bach has not used it elsewhere.

*104 (604) Ach Gott, wie manches Herzeleid.

The hymn is attributed to Martin Moller. Witt directs it to be sung to the tune “Vater unser im Himmelreich” (see No. 65 supra). In Cantatas 3, 44, 58, 118, 153 Bach uses another melody for the hymn (see No. 139 infra).

†105 (605) Ach Gott, erhör’ mein Seufzen und Wehklagen.

The hymn is by Jakob Peter Schechs (1607-59). It is set in Witt to a melody of which there is a four-part setting among the Choralgesänge, No. 2.

106 (723) So wünsch’ ich nun ein’ gute Nacht.

The hymn is by Philipp Nicolai. It is set in Witt to a melody (Zahn, No. 2766) which Bach has not used elsewhere.

107 (641) Ach lieben Christen, seid getrost.

The hymn is by Johannes G. Gigas. Witt directs it to be sung to the melody “Wo Gott der Herr nicht bei uns hält.” Bach also associates the two. (See No. 119 infra.) He has not used elsewhere the melody proper to “Ach lieben Christen.”

108 (598) Wenn dich Unglück thut greifen an.

The hymn is anonymous. It is set in Witt to a melody (Zahn, No. 499) which Bach has not used elsewhere.

†109 (552) Keinen hat Gott verlassen.

The hymn is anonymous. It is set in Witt to a reconstruction of the melody of the “Rolandslied,” of which there is a four-part setting among the Choralgesange, No. 217.

Edition: current; Page: [52]

110 (632) Gott ist mein Heil, mein’ Hulf’ und Trost.

The hymn is anonymous. It is set in Witt to a melody by Bartholomäus Gesius (Zahn, No. 4421) which Bach has not used elsewhere.

111 (599) Was Gott thut, das ist wohlgethan, Kein einig.

The hymn is by J. Michael Altenburg. Witt directs it to to be sung to the tune “Kommt her zu mir, spricht Gottes Sohn” (see No. 90 supra). Its proper melody is in the Gotha Cantional of 1648 (Zahn, No. 2524). Bach has not used it elsewhere.

*112 (550) Was Gott thut, das ist wohlgethan, Es bleibt gerecht.

The hymn is by Samuel Rodigast. Its melody is used by Bach frequently in the Cantatas and in the “Three Wedding Chorals.”

*†113 (553) Wer nur den lieben Gott lässt walten.

The section “In Time of Trouble” contains seventeen hymns, four of which (Nos. 106, 109, 112, 113) are not in Witt’s corresponding group. Bach also disturbs Witt’s order. He deliberately selects No. 97, a fervent expression of faith, to begin it. The succeeding eight hymns (Nos. 99-106) indicate moods of distress and despair, culminating in No. 106, with its hopeless cry:

- Farewell, vain, worthless world, farewell!

- Farewell to friends, farewell to life!

Then the mood changes. The last seven hymns breathe courage and assurance, and Bach ends with, perhaps, his favourite consolatory hymn, Georg Neumark’s “Wer nur den lieben Gott”:

- Think not amid the hour of trial

- That God hath cast thee off unheard.

Edition: current; Page: [53]

(a) The Church Militant Von der Christlichen Kirchen und Worte Gottes (476-497).

*114 (480) Ach Gott, vom Himmel sieh darein.

The hymn is by Martin Luther. It is set in Witt to the original melody. Bach uses it in Cantatas 2, 77, 153.

†115 (481) Es spricht der Unweisen Mund wohl.

The hymn is by Martin Luther. There is a four-part setting of its proper melody (attributed to Luther) among the Choralgesänge, No. 92.

*†116 (482) Ein’ feste Burg ist unser Gott.

The melody of Luther’s hymn occurs in Cantata 80 and the Organ Preludes, and there are two four-part settings of it among the Choralgesänge, Nos. 74, 75.

*†117 (483) Es woll’ uns Gott genadig sein.

The hymn is by Martin Luther. Its melody occurs in Cantatas 69 and 76, and there are two four-part settings of it among the Choralgesänge, Nos. 95, 96.

*118 (485) War’ Gott nicht mit uns diese Zeit.

The hymn is by Luther. The melody, attributed either to him or to Johann Walther, is used by Bach in Cantata 14.

*†119 (486) Wo Gott der Herr nicht bei uns hält.

The hymn is by Justus Jonas. Bach uses its melody in Cantatas 73, 114, and 178, and there are four-part settings of it among the Choralgesange, Nos. 383, 385, 388.

*†120 (479) Wie schön leuchtet der Morgenstern.

The hymn is by Philipp Nicolai, to whom also the tune is attributed. Bach uses the melody in Cantatas 1, 36, 37, 49, 61, 172, and an Organ Prelude. There is a four-part setting of it among the Choralgesänge, No. 375.

(b) God’s Holy Word.

*121 (610) Wie nach einem Wasserquelle.

The hymn is by Ambrosius Lobwasser (1515-85). Louis Bourgeois’ melody, to which it is set in Witt, occurs in Edition: current; Page: [54] Cantatas 13, 19, 25, 30, 32, 39, 70, 194. “Ainsi qu’on oit le cerf bruire” is its original title. In German hymnody it is known as “Freu’ dich sehr, O meine Seele.”

*122 (477) Erhalt’ uns, Herr, bei deinem Wort.

The hymn is by Luther. Bach uses its melody in Cantatas 6 and 126.

123 (520) Lass’ mich dein sein und bleiben.

The hymn is by Nikolaus Selnecker. In Witt it is directed to be sung to “Ich dank’ dir, lieber Herre” (see No. 144 infra), or “Ich freu’ mich in dem Herren” (Zahn, No. 5427). Neither the latter nor the hymn’s proper melody is used by Bach elsewhere.

While Witt’s corresponding group illustrates promiscuously “The Christian Church” and “God’s Word,” Bach prefers to treat the two ideas separately. Hence, the section contains two parts: (a) “The Church Militant,” Nos. 114-120; and (b) “God’s Holy Word,” Nos. 121-123. In the first part, with one important modification, Bach follows Witt’s order. He begins (No. 114) with Luther’s version of Psalm 12, the fourth stanza of which sets forth the Church’s mission:

- Grant her, O Lord, to keep the faith

- Amid a faithless nation,

- And keep us safe from sinful scathe

- At length to reach salvation.

- Though men their part with Satan take,

- No powers of Hell can ever shake

- The Church’s sure foundation.

To the taunt (No. 115; Luther’s Psalm 14), “The fool hath said in his heart, There is no God,” the Edition: current; Page: [55] Church (Luther’s Psalm 46) (No. 116) answers confidently:

A stronghold sure our God is He.

In No. 117 (Luther’s Psalm 67) the Church prays for the enlargement of her bounds:

- That Thy way may be known on earth,

- Thy grace among all nations.

Nos. 118 and 119 (two versions of the 124th Psalm) picture the Church militant and victorious:

- Our help on God’s own name doth stand,

- Who hath made heaven and earth.

The last hymn (No. 120) is a vision of the risen Church glorious, the Spouse of Christ.

The second part is prefaced appropriately (No. 121) by Psalm 42, wherein the Church declares her longing for the pure waters of God’s Word. In No. 122 she prays for grace to remain constant. No. 123 expresses the same thought; but, as is so often the case with Bach, in an intimate and personal manner.

In time of War Um Friede (498-513).

124 (498) Gieb Fried’, O frommer, treuer Gott.