CHAPTER I.: 1835–1851.

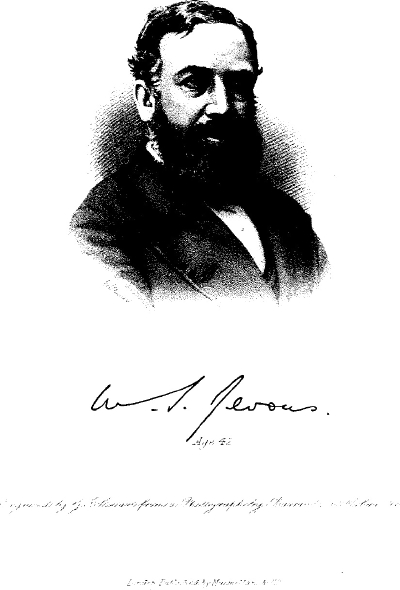

William Stanley Jevons, the son of Thomas and Mary Anne Jevons, was born at No. 14 Alfred Street, Liverpool, on the 1st September 1835.

The Jevons or Jevon family (for the final s was first added by Stanley's grandfather) is evidently of Welsh origin, but they had been settled in Staffordshire for many generations. At Cosely in that county Timothy Jevon, the great-grandfather of Stanley, lived; and here his grandfather, William Jevons, was born and grew up to manhood. William Jevons had but slight educational advantages, but he was endowed with a great deal of good sense, and was a man of strong affections and of much religious feeling. Having been brought up at home and employed in his father's trade of nail-making, he became assistant to a Mr. Stokes, engaged in the nail trade at Old Swinford, and it was to increase the business of Mr. Stokes that he removed to Liverpool at the end of the year 1798, accompanied by his wife and young family, consisting of three sons and a daughter. He had not been long in Liverpool before he was enabled, with the assistance of capital lent him by a friend, to commence business on his own account as an iron merchant. Mr. William Jevons gave to all his children

Edition: orig; Page: [2]

the best education in his power, and when his eldest son Thomas grew up he took him into his own business, and before long made him a partner. Later on, Timothy, the youngest son, joined the firm, which was known as Jevons and Sons.

Mr. William Jevons attended the Unitarian chapel, then situated in Benn's Garden, and his second son William became a Unitarian minister, after receiving his college education at York, then the home of Manchester New College. He was an intellectual, cultivated man, but owing to a change in some of his opinions he early left the ministry. He wrote several books—one of them a small book on astronomy for the use of schools. Between him and his nephew Stanley there was great affection and sympathy, and they corresponded a good deal.

Mr. Thomas Jevons, the father of Stanley, was a man of much ability in many ways, and there is no doubt that Stanley inherited a love of science from him. He was greatly interested in all new engineering schemes, and was acquainted with the first railway makers, Stephenson and Locke. In 1815 he constructed probably the first iron boat that sailed on sea water, and in 1822 he made an iron life-preserving boat, and also a model of a floating ship or landing-place for steamboats. He supported the scheme for the construction of the Thames Tunnel, by which he lost a considerable sum of money. In 1834 he published a small book called Remarks on Criminal Law, and in 1840 a pamphlet entitled The Prosperity of the Landholders not Dependent on the Corn Laws. In later life Stanley described his father as “one of the most humane of men,” and as being remarkable for “a calm clear mind.” He was of too shy and retiring a nature to go much into general society, but he was always the devoted friend of his children, even when the cares of business pressed most heavily upon him.

On the 23d November 1825, Thomas Jevons was married to Mary Anne, the eldest daughter of William Roscoe, the well-known author of the Life of Lorenzo de' Medici and of the Life and Pontificate of Leo X. Mrs. Thomas Jevons was about thirty at the time of her marriage. Her youth had been spent at Allerton Hall, near Liverpool,

Edition: orig; Page: [3]

where her father lived until the loss of his fortune caused him to remove, about the year 1820, to a small house in the immediate neighbourhood of Liverpool. She was remarkably handsome, with very fascinating manners, and her mind had been cultivated by constant companionship with her father and by the intellectual society which she enjoyed under his roof. She inherited a good deal of her father's poetical talent, and was the authoress of a small volume of poems, printed for private circulation. She also edited the Sacred Offering, a collection of poems which came out in yearly volumes for several years, and the contents of which were chiefly written by members of Mr. Roscoe's family, for his younger daughter and several of his sons also inherited more or less of his talent. Mrs. Thomas Jevons was a woman of strong religious feeling. Like her husband, she had been brought up a Unitarian.

Although Stanley was the ninth child of his parents, only three of those older than himself survived beyond babyhood: Roscoe, born 1829; Lucy Anne, 1830; and Herbert, 1831. At the time of his birth his mother was still mourning the loss of a twin boy and girl who had died of influenza in 1834, and of another baby boy who had died in the spring of 1835. This must have made Stanley as a young child somewhat solitary in his plays and occupations, for the two nearest to him in age were his brother Herbert, who was four years older, and his sister Henrietta, three and a half years younger, than himself. He had also a younger brother, Thomas Edwin, born in October 1841, who, though too young to be a companion in childhood, was the closest friend of his later life.

The house in Alfred Street had been built for Mr. Thomas Jevons, from his own designs, at the time of his marriage, but it was not large enough for his increasing family, and when Stanley was about a year and a half old, his father removed to No. 9 Park Hill Road, one of two new houses built from his own designs—for Mr. Thomas Jevons took great pleasure in planning houses, and showed much skill in doing it. The other house was occupied for the first few years by his brother, Mr. William Jevons, and later by his younger brother, Mr. Timothy Jevons, and his family. His

Edition: orig; Page: [4]

father and mother, Mr. and Mrs. William Jevons, lived in a large old house close by, the garden joining his son's. At that time Park Hill Road was almost in the country: besides the large gardens attached to the houses there were fields and lanes close by, so that the children could have plenty of healthy out-door life. Mr. Thomas Jevons' house is still standing, and is now used for the Sunday school belonging to the Unitarian Chapel in Toxteth Park Road. The rooms remain the same as he planned them, but the surroundings are so changed that it is difficult, if not impossible, to realise the place as it was. The gardens are all gone, and the neighbourhood is built up with a poorer class of houses, and is now part of the town.

The first thing that Stanley could remember occurred during the great storm of January 1839, before he was three and a half years old. One of the chimneys of the house of his uncle, William Jevons, was blown down, and Stanley's mother was so much alarmed that she had her children roused from their beds and carried down to the cellar for safety. He could also remember suffering, when he was very young, from an attack of croup in the night, and being put into a warm bath, with the doctor standing by. But on the whole he retained a less vivid impression of his very early childhood than many people of ordinary ability do.

Of all her children, Stanley was the one who most resembled his mother in personal appearance. His eyes, which were a blue-gray in colour, were, like hers, large and full of expression, and were shaded with peculiarly long dark eyelashes, which greatly added to their beauty. A friend writing of him says: “I remember him when such a little fellow with bright curly hair. What a fine noble boy he was!” Another friend remembers his running into the room one day when she was with his mother, and asking for some employment, saying with great energy, “I cannot live unless I have something to do.” As a young child he almost always had occupations which he made for himself, and nothing tried his naturally passionate temper more than to be compelled to leave the interest of the moment whilst still engrossed in it.

His sister says that Stanley learned to read and write

Edition: orig; Page: [5]

without any difficulty, and certainly the following letter at six years old in his own handwriting is very good for a child of that age:—

“My dear Grandpapa—When will you come home? I am six—I was six on Wednesday, and Mamma gave me a paint box. There was a beautiful rainbow to-night. I have got a sixpenny little boat. Good-bye, dear grandpapa.—Your affectionate Stanley Jevons.”

Another little letter has also been preserved, written when he was seven years old, to Dr. Richard Roscoe, his mother's younger brother, who was a frequent visitor at her house.

“Dear Uncle—I thank you for the picture. I sometimes say my lessons well. I draw almost every day, and I paint sometimes. Nurse is going, and another is coming. Tommy is a very big boy, and is very funny. When will you come again and see us? Henny has got a bad cold. Good-bye.—Your affct. nephew, Stanley.”

Mrs. Thomas Jevons always encouraged her children in their love of drawing and music; and Stanley's love of music, which he inherited from both his parents, was through life one of his greatest pleasures. His mother also taught him botany, in which he took great interest, and he always kept the little microscope which she had given him to examine flowers with. From her, too, came his first teachings in political economy, as she read with him Archbishop Whateley's Easy Lessons on Money Matters, written for children. He was not what is usually called a precocious child, but he was very thoughtful and extremely observant, and eager to acquire information. In speaking of himself he once remarked, “I am said to possess much curiosity, and I often felt a positive pain in passing any object which I could not understand the construction and meaning of.”

He was always very dexterous in using his fingers. His uncle, Dr. Roscoe, gave him a set of bookbinding tools, and I have a little book bound by him when quite a young boy, the binding of which is a very creditable piece of workmanship for his age.

For outdoor occupations Stanley had his own little garden in which he worked; he had also some ducks for

Edition: orig; Page: [6]

pets, of which he seems to have been very fond. But his greatest pleasure was to be with his eldest brother, Roscoe, who had great talents for mechanical construction. Their workshop was a coach-house and stable, and here many happy hours were passed by Stanley in watching and helping his brother. When Mr. Timothy Jevons came to occupy the third house instead of his brother William, Stanley had the companionship of two boys about his own age, and the cousins must have had frequent opportunities of meeting, for they had the kindest of grandparents, who permitted their garden to be the constant play place of the two families of cousins.

Until the failure of his mother's health, Stanley's home must have been as happy a one as a child could have, and he always felt it to have been so; but, in 1845, Mrs. Thomas Jevons became so ill that she went to London, chiefly to be under her brother Dr. Roscoe's care, and in November of that year she died there without seeing her children again.

The following letter was written to his mother whilst she was away:—

“My dear Mamma—I hope you are better. I am quite well now, and I am getting on very well in my lessons. I am translating very small histories of great men, and of countries, and I know the first twenty propositions of Euclid, and I also write French exercises and the verbs, and exercises in English composition, and write copies. Yesterday Roscoe, Herbert, and I took a very long walk to Allerton Hall. We started at half-past three, and went up through the Prince's Park, and then went past Mrs. M—'s old house into Aigburth road a great way, and through roads, and at last found our way by finger-posts, and came back the proper way about six o'clock, when it was nearly dark, not very much tired; and in the morning we went to chapel, but papa did not go. We are getting on very well in everything. I found a book of Uncle Richard's, called the Prescriber's Pharmacopæia. Roscoe, Lucy, Herbert, I especially, and all the rest of us, send our best love. Good-bye.—Your most affectionate son,

“William Stanley Jevons.”

Edition: orig; Page: [7]

From this time Stanley's eldest sister filled, as far as she could, her mother's place in the home; and though a governess continued to reside with them for a year or two, it was to their sister that the younger ones were indebted for a love and care which can only be described as motherly, and which was returned on their parts by the warmest affection for her. Until he was more than ten years old Stanley was taught at home by a governess, but early in 1846 he became a day scholar at the Mechanics' Institute High School in Liverpool, which his brother Herbert was attending. The late Dr. Hodgson, afterwards Professor of Political Economy at Edinburgh, was then headmaster of the High School. Two or three of the school reports of Stanley's conduct and progress have been preserved, with Dr. Hodgson's comments to his father. In April 1846 he writes, “W. S. seems a very fine little boy,” and in January 1847, “W. S. J. will do very well indeed, if he gain courage and spirit as he grows older.” The French master writes in the reports that he is very good and very industrious, but far too quiet, makes no noise, and does not read above his breath. He adds, “I should go to sleep if all the class were like him.”

In after life Stanley felt that he had gained much from Dr. Hodgson's teaching; and he regretted that his father had removed him so soon from the school. In June 1847 he received the prize of his class, a large volume of Crabbe's poems, in which the following inscription is written:—

“This Book, being one of the Prizes granted by George Holt, Esq., is assigned to W. S. Jevons, as first pupil in the 6th class of the High School, his conduct and attention throughout the year having been not less satisfactory than his progress.”

Mr. Thomas Jevons at this time removed both his sons from the High School, because he thought some of the boys attending it were undesirable companions for them, and after the summer holidays, Stanley was sent to Mr. Beck-with's private school in Lodge Lane as a day scholar.

In January 1848 the firm of Jevons and Sons failed. Stanley never forgot one Sunday when, instead of going to chapel as they were in the habit of doing, his grandfather, father,

Edition: orig; Page: [8]

and uncle were shut up all the morning together with the books of the firm. He was much puzzled and rather shocked at the proceeding, which was his first intimation that anything was wrong.

This misfortune made a great change in the circumstances of the three families in Park Hill Road. The houses were given up at once, and Mr. Thomas Jevons removed with his family to No. 125 Chatham Street. Mr. William Jevons, who had lost his wife in 1846, became from this time a member of his eldest son's household. He brought with him an organ, on which Stanley used to play a good deal; and he did it well enough to give much pleasure to his grandfather and father, who were both very fond of music, although unable to play any instrument themselves.

Owing to the failure it had become necessary for the family to live as economically as possible. Stanley was old enough to understand this, and it early taught him to be very careful in what he spent, and always to try to lay out his small sums of money to the best advantage. He still continued at Mr. Beckwith's school. He used to speak of this as almost a wasted time in his education after the teaching he had had at the Mechanics' Institute High School; but he acknowledged that the attention paid to Latin at Mr. Beckwith's was of service to him, and saved him future trouble, for he had no natural talent for learning languages. His half holidays were often spent in walks with his two cousins, who still lived near. The summer holidays were spent either at Park gate, a little old-fashioned place at the mouth of the Dee, or at West Kirby, also on the Dee; and he always retained an affection for that neighbourhood.

He was at this time a quiet thoughtful boy, very shy and reserved, and quite unconscious of his own abilities, but on 31st January 1849 his elder sister made the following entry in her diary: “In Stanley I see the dawning of a great mind.”

In the summer of 1849 Stanley went with his younger sister and brother to Nantwich, to pay a visit to his mother's sister, Mrs. Hornblower, whose husband was the Unitarian minister there. Aunt Jane had great affection for her nephews and nieces, and Stanley at different times spent

Edition: orig; Page: [9]

many pleasant weeks under her roof. During this visit his father wrote to him: “I must begin this letter by thanking you for your manly and excellent note to me. In it I see signs of ripening thought and judgment, which gives me great joy. In this visit you are not only adding vigour to your bodily frame, but I feel satisfied that you are gaining manliness, and gaining some little power over that natural timidity of character which is the worst or perhaps I may say almost the only weakness you have. A little more observation of the world, and a habit of looking closely into the origin of the fears that create the timidity or bashfulness which you occasionally display, will help you wonderfully to get the better of it.”

After the summer holidays of 1850, when he was just fifteen, Stanley was sent to London to attend University College School; and for a short time he stayed with his brother Herbert in Harrington Street. Afterwards he lived for several months in Gower Street, in the house of a lady who received as boarders boys attending University College School. Here he was very unhappy, partly perhaps because it was the first time he had lived with strangers, but also because he had good reason to dislike his three fellow-boarders. Years afterwards he wrote in his journal that he never passed the house without a feeling of dread at the remembrance of what he suffered there.

Five weeks after his arrival in London he wrote to his father: “Everything is done so systematically that I like the school altogether very much.” On the 17th of November 1850 he again wrote to his father: “I have been a grand sight-seeing to-day, and have walked nearly from one end of London to the other. I started a little before ten o'clock, and went straight to St. Paul's. They do not let you go into the choir if you come very late, and I only saw what I had seen before. I then went and saw Smithfield and St. Bartholomew's and the Post Office, after which I went along Cheapside to the Exchange, etc. I next found my way to the Tower of London, and then to the Thames Tunnel, into which I went. From the Tunnel I came back and went along the Strand, Whitehall, St. James's Park, and Green Park, the Exhibition in Hyde Park, and then along

Edition: orig; Page: [10]

Oxford Street, Regent Street, and home, where I arrived at half-past four ready for dinner. The Glass Palace is getting on famously, and I saw some of the glass. All the work looks very light and slender, but I suppose that the iron will be quite strong enough. Great crowds go to see it. If the half-finished building makes such a stir, what will the Exhibition itself do!”

He was greatly interested in the “Glass Palace,” and often visited it. On the 1st of June 1851 he wrote to his father: “Last Wednesday I went to the Exhibition. I think that nothing can be more astonishing or wonderful than to walk round the galleries, or to look from one end to another, and though I had heard every one talk of it for a long time, and had seen numbers of pictures of it, I did not expect it to be so splendid. It was a long time before I could stop to look at any particular thing instead of staring about, and still longer before I could leave the nave. I liked the organs especially, and perhaps spent too much time in listening to them instead of looking at the other things. I spent some time in watching cotton and flax spinning and weaving, which I never properly understood before.”

Again, on the 5th of July 1851: “I went last Monday to that place of all places, the Great Exhibition. I went through a good part of the south-western division of the building, where the minerals, chemicals, vegetable productions, agricultural implements, and hardware things are. I have learnt a great deal since I came to London about minerals and the metals, particularly from my chemistry and partly from museums; and I intend if I have time in the holidays to arrange all the minerals and fossils I have got at home. I saw also the Illustrated London News steam press, which is very wonderful. I had not observed the hydraulic press from the Britannia Bridge before. What an immense thing that is! I heard Gray and Davidson's organ at the east end of the nave played, and liked it better for its size than the largest. In the American part some ass of a Yankee had put a piano with a fiddle, and by turning a handle the fiddle begins to squeak; and, to the disgrace of mankind, it must be said that there is as great a crowd round this thing as round anything else almost in the place.”

Edition: orig; Page: [11]

His father was much pleased with his progress at school. On the 19th November 1850 Mr. Jevons wrote: “I am glad to see the first report of your character and progress and standing in your school. It is very good, but only what I expected from you.” And again on the 18th March 1851: “I was not a little gratified by the receipt of your character as pronounced by your several masters. I have no doubt of its truthfulness, and it is highly honourable to you. Go on in like manner, and prosper you must in whatever walk of life you select.” On the 28th June 1851 he wrote: “I shall be very glad when your holidays commence, for it seems a long time to be deprived of your society, and I shall begin now to look to you for assistance in family affairs by consultation and advice. … I need the help of a friend in whom I can trust, and I must bring you forward to take part in the battle of life, young as you yet are.”

At midsummer 1851 Stanley returned to Liverpool, bringing with him five prizes, three first and two second. His school-days were then at an end, for at that time boys did not remain at University College School beyond the age of sixteen, and he would attain that age during the holidays. He was already beginning to think about some of the difficult problems of philosophy, and before his return to college in October he had written an essay on “Free Will and Necessity,” in which he tried to prove that the arguments in favour of the doctrine of necessity were much stronger than those in favour of the doctrine of freedom of will.

Looking back upon his early boyhood, he wrote in December 1862, when he was twenty-seven years of age: “When quite young I can remember I had no thought or wish of surpassing others. I was rather taken with a liking of little arts and bits of learning. My mother carefully fostered a liking for botany, giving me a small microscope and many books, which I yet have. Strange as it may seem, I now believe that botany and the natural system, by exercising discrimination of kinds, is the best of logical exercises. What I may do in logic is perhaps derived from that early attention to botany. My Uncle Richard also gave me Henslow's Botany. He presented me

Edition: orig; Page: [12]

with certain bookbinding tools, which I had the greatest pleasure in using or trying to use. I am yet partial to bookbinding, and shall sometime perhaps begin it again. I used to think I should like to be a bookbinder or bookseller—it seemed to me a most delightful trade—and I wished or thought of nothing better. More lately I thought I should be a minister, it seemed so serious and useful a profession, and I entered but little into the merits of religion and the duties of a minister. Every one dissuaded me from the notion, and before I arrived at any age to require a real decision, science had claimed me.”

At the same time he recalled some of his thoughts about religion at this early period: “I was not without a tendency to inquire into the subject. The Gospels seemed worth more than reading; they were worth analysing and making into a rigorous history of Christ. And this I actually undertook to do. While living in Chatham Street, perhaps about the year 1850, I began the work during the quiet of Sunday afternoons in my small bedroom, where I had a very diminutive table, with an inkstand and a few little things in a study-like array. By noting down the facts as stated in the Gospels, and comparing them and arranging them in chronological order, I intended to form a regular Life. But altogether, apart from any difficulties which older persons might meet, I found the task very perplexing for my then powers. What most impressed the work on my memory is that the second or third Sunday my father appeared suddenly in my room. As this was at the very top of the house, and he was usually sitting during the afternoon after dinner in the parlour, I expect he must have missed me and come to see my occupation. But finding me writing, he pressingly inquired the subject, which I was at last almost forced to confess, to my entire confusion and dismay.”

Of his secret aspirations during his school life in London he wrote at the same date: “It was during the year 1851, while living almost unhappily among thoughtless, if not bad companions, in Gower Street—a gloomy house on which I now look with dread—it was then, and when I had got a quiet hour in my small bedroom at the top of the house, that I began to think that I could and ought to do

Edition: orig; Page: [13]

more than others. A vague desire and determination grew upon me. I was then in the habit of saying my prayers like any good church person, and it was when so engaged that I thought most eagerly of the future, and hoped for the unknown. My reserve was so perfect that I suppose no one had the slightest comprehension of my motives or ends. My father probably knew me but little. I never had any confidential conversation with him. At school and college the success in the classes was the only indication of my powers. All else that I intended or did was within or carefully hidden. The reserved character, as I have often thought, is not pleasant nor lovely. But is it not necessary to one such as I? Would it have been sensible or even possible for a boy of fifteen or sixteen to say what he was going to do before he was fifty? For my own part 1 felt it to be almost presumptuous to pronounce to myself the hopes I held and the schemes I formed. Time alone could reveal whether they were empty or real; only when proved real could they be known to others.”

CHAPTER II.: 1851–1854.

In October 1851 Stanley returned to London to attend classes at University College, and he was fortunate enough to find a home in the house of his aunt, Mrs. Henry Roscoe, who then lived at 9 Oval Road, Camden Town. Here he remained all the time that he was at University College, and he was very happy, for besides his aunt's kind care, he had the companionship of his cousin Harry (now Sir Henry Roscoe), with whom he formed a lasting friendship.

At this time his favourite study was physical science, especially chemistry, and at Easter 1852 he received at College the silver medal for chemistry, and at Easter 1853 the gold medal for the same subject. In 1852 he also received the first prize for Experimental Natural Philosophy. In July 1852 he matriculated at the University of London, and took honours both in chemistry and botany.

Soon after receiving the silver medal he wrote to his father: “I am very glad that you were so pleased about the medal, as I see from yours and Lucy's letters, but I have no intention of trying very hard or injuring my health at all to get any more—that is, any more prizes, though, of course, I shall try to learn all I possibly can while I have the opportunity at college. If a person goes into an examination people are always disappointed if he does not come off one of the first, and for that reason I was rather sorry after I had gone into the chemistry examination, as I had no right then to expect anything more than one of the last certificates. I am afraid now that you will be disappointed at my not getting anything at the college examination in

Edition: orig; Page: [15]

June, for though I may possibly get a certificate in Greek, and possibly either in Latin or mathematics, I have no chance of any prize, and this is literally true as far as I can judge at present. As to the matriculation, I shall try to pass in the first division, and if I pass the examination at all, I shall probably try to pass the examination in honours for chemistry; but you must not expect any prizes here either.”

To his sister Lucy, before he knew the results of the matriculation examinations, he wrote: “I daresay you will want to hear about the matriculation, and so I will tell you that it has all gone off very well. … I am not at all afraid of being plucked, and the only thing that I think will put me in the second division, if I am so, will be the history, for all the examinations were much easier than those at college. … I have not told you, I think, that I was invited by a student I know at college named Colvill, the nephew of Dr. Sharpey, with whom he lives, to go and get tea there. … He is a very nice old fellow, and one of the best physiologists alive. He attended Mr. Graham's class this year with all the other students, and since Easter has been working all day in the laboratory, with Dr. Williamson telling him how to do the things. You must not complain of me making messes and blows-up in the cellar if an old chap of sixty begins to learn to do it. I am going to bring out something fine next holidays in the chemistry line!”

Early in January 1852 his grandfather, Mr. William Jevons, had died at his father's house, at the advanced age of ninety-one, but Stanley was not at home at the time, as he had remained in London for the Christmas holidays.

During the summer vacation of 1852 Stanley began to keep a journal, the first entry dated is the 23d August 1852: “The college lectures ended on the 15th of June, and the examinations in mathematics, Greek, and Latin—for the chemistry ended at Easter—were finished on the next Monday. The mathematical exam, was six hours long, while the chemistry one had been eight, but nevertheless the mathematics tried me far more, and before the end I got quite stupid, to which I must partly attribute my low place. Soon after was the distribution by the Earl

Edition: orig; Page: [16]

of Carlisle. My certificates were fourth in Latin, fifth in Greek, and sixth with Colvill in mathematics.

“The matriculation was to begin on the 6th July, and till then of course I worked hard; I had got up all the Latin and Greek for the college exams., and so attended chiefly to English history and grammar, chemistry and botany. It was only a few months before that I had begun to think of going up in botany, and considering that I did not know any more than I had learned from reading a few small ‘Introductions,’ etc., and Henslow's Botany, with my botanising at West Kirby for six weeks, it was rather adventurous. But I went over the orders again, and learnt Lindley's Elements, and wrote home for Henslow's to read again. In the chemistry I learnt the inorganic exclusively, as that only is required in the pass. Sam Archer now came to stop with us to pass the matric. The examinations were from ten to one, and from three to six on the 6th, 7th, 8th, and 9th of July. The first exam, in mathematics I did only pretty well, and the history in the afternoon decidedly badly, so much so as to put me into rather bad spirits, but all the rest was very easy, and the geometry and grammar were the most pleasant of all. I had to try most of course at the chemistry on the second afternoon, and was satisfied with what I did. The natural philosophy on the third afternoon I missed. In the two hours between, Sam and I went to a coffee-house, where we looked over a book, or learned off our notes for the afternoon; but the heat, everywhere indeed, was most tremendous.

“On the Saturday, after the exams, were finished, Sam and I set off for an excursion to Epping Forest. We went by railway to Tottenham, from which we walked very slowly to the River Lea. There we had a two hours' row on the canal, which was rather a new thing to me. We found the walk to the Forest rather longer than we expected, and did not reach it till nearly seven, though we had set off at ten in the morning. The Forest was a splendid place, and quite wild, though the trees are very small; but we could not stay long from the lateness. We then walked to Chigwell, which I wanted to see very much, as it is a part of the scene in Barnaby Rudge, my favourite novel; but we missed seeing

Edition: orig; Page: [17]

the Maypole, which I believe really exists, and is called Queen Elizabeth's Lodge. We got to Chigwell at eight o'clock (!), and considering we were ten or eleven miles from home, without any prospect of getting an omnibus, and very much tired already, we were rather alarmed, but set off at once, determined to walk it. We reached Bow after ten, but fortunately found an omnibus just starting, by which we got to St. Paul's, from which we walked home, considerably tired. The country was very beautiful, and in the naturalising way I found several new flowers, and a glow-worm for the first time.

“On the Monday I set to work seriously for the honours, having few doubts of passing in one of the divisions. I worked chiefly at home for about seven or eight hours a day, and finished nearly all I intended by the 23d—the day of examination. In the chemistry I really believed I should do very badly, and in the examination I actually felt quite lazy and careless! But the botany examination in the afternoon of the same day was far more interesting. I wrote concisely, and therefore I suppose well, though I made several mistakes. The question on the chemical products of assimilation I did easily of course, as I had learned it in the chemistry. Sam went in for zoology with four others, while I had only one other, named Turner, who like me went in for chemistry. I got home with a bad headache, but managed to get to the 8.45 mail train, by which I got to Liverpool at four in the morning, and after spending the day at Chatham Street, I went over to West Kirby with papa in the afternoon.

“I set to enjoy myself as much as possible in one week, for I found that they were going to stop only one week more, and not ten or fourteen days. I had expected to be able to press nearly ten plants a day, having brought proper paper with me, but I believe I did not do more than one a day fit to keep, which is not surprising when I did not know how to set about it. The country was very pleasant certainly, and the weather pretty fine except on the Monday, and I enjoyed three or four bathes with Tommy very much in spite of the bad shore. One day we went an expedition to Hillbre Island, where Tommy, Henny, and myself spent most of the time in catching crabs, but I also got six new

Edition: orig; Page: [18]

kinds of seaweeds and several plants, including the fern Asplenium marinum. The rest of the time I spent pleasantly, sometimes lazily, in walking about the hill, sandhills, etc., but I was not in the best spirits.

“On again reaching Chatham Street the next Saturday I felt completely at a loss what to do first of the many things I intended to do. I began, however, on the Monday by clearing out my work bench, which with the bottles, cupboard, etc., I found in a very dirty state. It was a long and unpleasant job, but I made it very nice in a little time, putting all the glass apparatus in a box by themselves, so as to be out of the way. The only thing I did in chemistry was to put some salts to crystallise on the kitchen chimneypiece, but they have not succeeded at all, and to make some acetic acid from old sour beer.

“I at last began my herbarium by buying three quires of foolscap paper to put the specimens on, cheating myself as usual by buying it at is a quire when much cheaper paper would have done equally well. I soon after bought six feet of half-inch board fourteen inches wide to make the shelves, in which and other things I was chiefly occupied till within the last few days.”

The next entry is dated the 26th of August: “My chief, almost exclusive, occupation lately has been botany. The herbarium is now nearly finished, for I have put shelves in one compartment, as much as I am going to do these holidays, made the covers and labels for all the orders I require now, and mounted most of the specimens I have yet got, in number between fifty and sixty. I have also pressed a good many, chiefly out of the Parliament Fields, where there are yet enough to last me some time. I got several also by an expedition to Upton and Moreton with Sam Archer, and I got several garden plants too. I have not altogether omitted the less agreeable part of botany, the learning of the orders. I did not mention, I believe, last time that on Saturday night I heard for the first time that I had got the prize in botany at the matriculation. Turner is the name of the other one who went in with me, and he has passed too, and also has got the prize in chemistry, in which I am second with another person.

Edition: orig; Page: [19]

“I have often thought much about what is called cleverness and genius. The oftener an action is repeated, the more easy is it to perform it again, and the more perfectly will it be performed. It is by long repetition that workmen or jugglers acquire such perfection, and the only credit given to them is for their diligence. But I think that is exactly the same case with students, for if they have been accustomed for a long time to study diligently, but particularly in a good way, they get practised or clever in acquiring knowledge, while those who have been lazy or have studied in a careless manner cannot expect to become expert in it. I know that at least since I went to Mr. Beckwith's I have worked pretty hard, and I am very sure that if I had not I should never have got the prizes I have. By this time, perhaps, I have become more practised in acquiring knowledge than some others who have not attended to study, and this it is that constitutes all the cleverness I may have. …

“Friday, 3d September.—On Tuesday I went with Sam Archer to get some shells from the bottom of ships in the graving docks. I got three kinds and a seaweed. Wednesday was my birthday, when I became seventeen, but I began the day in an unusually bad humour. I began a letter to Aunt Jane, of which, however, I could finish only a few sentences, and had hard work in keeping my agreement with Sam Archer to go to Crosby. We set off all right, however, and at the railway I met a man named Sanson, who is a very good botanist, though a custom-house clerk, and I should like to know him. We wandered about the Crosby sandhills for several hours, and I got a good many rather nice specimens, as Triglochin palustre, Gentiana amarella, Parnassia palustris, Anagallis tenella, Echium vulgare, Euphorbia paralias, Euphrasia officinalis, Spergula nodosa, etc., and Sam found some willows, with numbers of pretty good caterpillars, hawks, and pusses. I got home at six, got my tea, pressed several plants, and had to get ready immediately for the Philharmonic concert, but as I had to sit by myself, and was, moreover, in a bad humour and tired, I enjoyed it but little, as I expected. It took all Thursday morning to examine and press my plants, in which, however, I succeeded better perhaps than I have ever done before.

Edition: orig; Page: [20]

“Last night I spent chiefly in sorting what few shells I have. … This morning I walked along the docks a little, and was fortunate in finding some large foreign snail shells on some dye-wood. I am going to set to work to-day at arranging the minerals, and have got the cardboard for the boxes.”

On the 24th of September he writes: “I have let a long time pass over without any entry, and had once indeed resolved to give up my Journal. But I daresay I shall find it easy to write regularly when I am working hard at London, for my energy is like that of others I have heard of, never excited but by pressure and difficulties. For instance, during the whole of these holidays I might easily have done two or three hours' work a day at lessons and got a great deal done, but I have not done so for more than a week altogether. I am, indeed, very much vexed at having done so little these holidays, for during two months I have only collected about fifty or sixty plants, arranged them as an herbarium, arranged my minerals, gone a few excursions and walks with Sam Archer, read grandpapa's life, and done some few other things hardly worth mentioning. During the same time at college I have no doubt I could have done as much while attending regularly to all my classes. I think this will be the last opportunity I shall have of wasting my time, for till next July I shall be at college almost continually, and then (after a short time in the country, I hope) I shall go at once to business, and need not hope for any more holidays for some time.

“The idea that I have formed of the manner of spending the next few years, though of course I cannot expect that it should turn but half as I like, is to devote this next session at college to learning as much science as possible, especially natural philosophy, mathematics, botany, and chemistry, the last perhaps less than the others, because I am more advanced in it. I shall spend some time also in walking over London, especially the remote and low parts, and during the season taking walks and excursions into the country to collect plants for my herbarium. After a short tour, most likely among the Lakes, on which I shall collect plants, I suppose I must begin some business directly, the nature of which

Edition: orig; Page: [21]

does not matter so much, but as far as I know at present, I should like that of a general broker, since there is more variety. The office, meals, etc., will occupy me from about eight in the morning till seven in the evening (though no doubt I could devote at least an hour of that to reading, particularly if it is light reading), and there will be left for real study at least two hours in the evening and one in the morning. I shall thus work for about eleven hours a day, but the eight of them spent at the office will not be nearly so fatiguing as the seven or eight at college, while the study in the evening will become, I expect, more a pleasure than a trouble. Of this study only a little will be given to science, and the rest to Latin, Greek, history, French, or German, etc. This appears a grand but practicable scheme, but I must be prepared to see it frustrated at any time, and to find it a far less easy job than I had expected—to accustom myself to going to business, in the middle of the noisy town for nothing but to write out dry letters, invoices, etc., run errands, and the like. But it has been done before under harder circumstances.

“I have done very little during the last few weeks worth mentioning. My minerals are most of them in neat boxes, and some of them with names. I have added about twenty new specimens to them, many of them pretty good, as iserine, several iron ores, two carbonates of copper, obsidian, etc., but I hope to get many more in London. I think I shall take a vow to spend the whole of the Christmas holidays in learning mineralogy and crystallography, and finishing the arrangement of my collection by putting a paper to each specimen telling its name, composition, form, and a little of its history. I shall buy the minerals chiefly which are mentioned in the chemistry, and study these chiefly, and thus shall be gaining something useful for the examination at Easter.

“I have collected very few plants lately. One or two days I spent in making up some stray sheets and plates of Roscoe's Monandrian Plants into four copies as complete as possible. The first, the most perfect that can be made, has all the printing, but wants nineteen plates, some of which Lucy will copy for it. I have, of course, looked well

Edition: orig; Page: [22]

through the book in doing this, but though it is very splendidly executed, I should think it was not of much use as a botanical work, since grandpapa's arrangement is not mentioned in the Penny Cyclopedia (Art. ‘Scitaminaceæ’). He has made also a great mistake in defending the Linnæan against the natural system. The former is no better an arrangement of plants than that would be of animals which made the classes depend on colour, as the white class, red class, brown class, etc. It might often happen that all of one natural class were of one colour, and were in one class of this system, as sometimes happens in that of Linnæus, while the variations in colour of single animals scarcely exceed those of plants in the number of the stamens and pistils. Linnæus has acknowledged the imperfection of his system by making the classes Didynamia and Tetradynamia, which are nothing more than natural classes.”

He returned to London at the commencement of the college session in October 1852, and continued his journal throughout the winter. On the 23d October he writes: “I am now fairly at work again for my last session, and shall try to get through a good deal of work, but rather with the intention of enabling myself to go on easily afterwards than of finishing up. During the first week and a half I had only chemistry, but though this took very little time, I got through little else, except reading the first three chapters of De Morgan's Trigonometry, and a few other things. In chemistry I began by reading the subject of the lecture up in a number of books, as Graham's Chemistry, ‘Heat’ in Encyclopedia Metrop., Library of Useful Knowledge, etc., but I found that while I got but little new from so many, it confused me very much, so I have left it off. In reading difficult mathematical things I found that the best way to make them out was to go over them very carefully for two or three days together, instead of puzzling yourself for several hours to understand one sentence or one mathematical transformation.

“On the 15th, Thursday, was the introductory lecture of the arts, by Professor Clough, on the Literature of England, but I did not make much out of it. The next morning I attended De Morgan's higher junior, and had the usual

Edition: orig; Page: [23]

lecture on our necessary notions of ratio, with which he always begins. Professor Potter in the afternoon gave us an introductory lecture on Force, as the universal agent, as in motion, heat, electricity, chemical action, etc. I also began the long job of copying out De Morgan's tracts, with those on ratio. I intend to do them all, as they come out in my classes, because I think that whenever I work at any of the subjects again I shall miss them very much; I also intend to have all De Morgan's books.

“A few days after I got here I went to the university at Somerset House, and got my three certificates for the matriculation and an order to the bookseller for my prize-books. I had to go several times to the bookseller, Richard Taylor, but at last fixed upon Regnault's Cours de Chimie, 4 vols., 21s.; Schleiden's Scientific Botany, 21s.; and Lindley's Vegetable Kingdom, with Glossary of Botanical Terms, about 35s. The rest of the £5 being taken in the binding.

“I have had several rather learned discussions with Harry about moral philosophy, from which it appears that I am decidedly a ‘dependent moralist,’ not believing that we have any ‘moral sense’ altogether separate and of a different kind from our animal feelings. I have also had a talk about the origin of species, or the manner in which the innumerable races of animals have been produced. I, as far as I can understand at present, firmly believe that all animals have been transformed out of one primitive form by the continued influence, for thousands, and perhaps millions of years, of climate, geography, etc. Lyell makes great fun of Lamarck's, that is, of this theory, but appears to me not to give any good reason against it.

“31st October.—I have been working steadily all this week at college. I have worked full nine hours a day, chiefly at mathematics, which I get to like more as I attend to it better. We have just finished what we are to do at present of double algebra and series, which I think rather interesting though hard. In the higher junior class we have been at ratio and fractions. I have finished copying out the four tracts on ratio and the one on series.

“The chemistry has been going on very slowly and stupidly, for we are only as far as gases, although we have

Edition: orig; Page: [24]

gone over the last few subjects very quickly. The best way to do well in the examination will be, I think, to work up the whole of Graham, and some out of Regnault, etc., well, a week or two before.

“In natural philosophy we have got to levers, but I do not like either the class or the present subject much. I have gone through the subjects in Potter's book.

“By myself I have given most of my time by far to mathematics, and have done nearly all the exercises for both classes. I have nearly finished reading Buff's Physics of the Earth, and have also been reading the introduction to Regnault's Chimie on crystallography, which I intend to study in the Christmas holidays. I think I shall try to make wooden models of the crystalline forms, and a Wollaston's goniometer. I have bought a few minerals since I came, but have chosen them badly. I shall spend about five shillings more on them before Christmas, and get chiefly those which are mentioned in the chemistry.

“I have long had a curiosity about the dark passage and arches between the Strand and the river, so, having read ‘The Strand’ in Knight's London, I went on Friday. The first thing I saw worth mentioning was the ‘dark arches’ under the Adelphi, but the first time I only looked in, and was afraid of going farther. Then after having a look at the Savoy Chapel, the only remains of the old Savoy Palace, I got down to the river below the arches by one of those extraordinary passages to the boats, and took courage to walk up through the arches. There were some women in them then, and I read a little time ago in a newspaper of some women who were found almost starved in them.

“Yesterday I made one of my excursions to Spitalfields. I walked to King's Cross, from there by the New Road and City Road to Finsbury Square, through Cannon Street to Bishopsgate Street, and from there into Spital Square. The appearance of the houses from the first was rather peculiar, and the greater proportion of the houses have the large weavers' windows running the whole width of the house, for the top storey at least. It was some time, however, before I found any of the wretched places I have heard so much of. One narrow lane was the worst, I think, that I ever

Edition: orig; Page: [25]

saw; almost every house had a dirty piece of paper in the patched and dirty window, with ‘Lodging for single men,’ at 2d. or 3d. a night. The chief rooms of the houses, opening of course to the street, were very small and exceedingly dirty, and by the light of the fires, for it was getting dark, I could see that there was nothing but a narrow bench or two inside. Nothing looks more unwholesome, also, than the crooked little back doors leading into a few filthy square feet of yard behind each house. There were a few of the bird traps on the tops of the houses so characteristic of the Spitalfields weavers.

“But I was most astonished at the great many improvements that are going on there. One wide road appeared to have been lately cut right through the worst part, and on either side I had an opportunity of seeing the backs of the houses over the empty spaces where other houses had been removed. In almost every street there seemed to be some building, and south of Spicer Street I came upon a whole batch of model lodging-houses, called ‘Metropolitan Chambers,’ with churches, schools, etc., around them. In another street I saw very clean, new, and handsome, though small, swimming-baths. The people often looked exceedingly wretched and destitute, but quiet and peaceful, and not the blackguardly set that you generally see. I shall go again soon.

“This afternoon I took a walk all over Westminster, beginning at Charing Cross, down Whitehall, past the Houses of Parliament, and as far as the Millbank Penitentiary, where I turned up through the poorer parts. There were several rather dirty narrow places, but great improvements are going on there also, such as the making of a grand new road, the Victoria Road, through the worst parts.

“Sunday, 7th November 1852.—I have little to put down this week, for I have done little but work quietly at college, mathematics chiefly, and we have been doing series—the binomial theorem and logarithmic series. In the higher junior we have just finished the fifth book of Euclid. I never feel satisfied with my knowledge of anything unless I have gone over it connectedly and systematically, and so

Edition: orig; Page: [26]

I am writing out the fifth book, shortly but distinctly, with De Morgan's proofs. In the chemistry we have had three or four lectures from Dr. Williamson instead of Graham. The subjects have been oxygen and hydrogen, and I have read them up in Regnault, as well for the chemistry as the French reading. In natural philosophy we are near the end of the mechanical powers; it is very necessary to know all this mechanics, of course, but there is very little interest compared with what there is in any of the parts of chemistry. The history class by Professor Creasy began this week, and we have had three lectures from him already, from half-past eight to half-past nine in the morning. It has been chiefly about Grecian history, and will be for several more days, I expect. I think I shall be interested in it, and though I shall read pretty much, I cannot expect to do well in the examination. I shall read a good deal of history after leaving college.

“Monday, 15th November.—Yesterday I explored Clerkenwell. I walked to King's Cross and by the New Road, Hamilton Row, Bagnigge Wells, Guildford Place, and Coppice Row to Little Saffron Hill. This I went down till near Holborn, when rather frightened by the appearance of the inhabitants of pickpockets, I dashed to the left and got to the site of Hicks Hall in St. John's Road. From there by St. John's Lane up to Clerkenwell Square, Jerusalem Passage, and Clerkenwell Green, where the Session House is. After examining this as well as the Close, Red Lion Street, and the surrounding neighbourhood pretty well, I struck out north, and having got as far as the neighbourhood of Northampton Square, which is, I believe, a good specimen of Clerkenwell, I returned by much the same way as I came. Clerkenwell seems to be the seat of a great many little manufactures, besides watchmaking, such as work-boxes, jewelleries, gems, musical boxes, etc. The genuine Clerkenwell has a quiet respectability and industrious appearance, and must be carefully distinguished from the neighbouring rascally parts, which are the headquarters of the pickpockets and thieves of London.

“Sunday, 19th December.—The last Sunday before Christmas has now come, and I must conclude my account of this

Edition: orig; Page: [27]

term before turning my thoughts to the Christmas holidays, and to home, which last, however, I hope they seldom leave.

“I have no walk worth describing this time, partly because the dark comes on so soon in an afternoon now, and partly because I have been pretty busy at home. I made an attempt at a walk through Bermondsey the Sunday before last, going to Fenchurch Street by railway, and walking across London Bridge; but it was nearly dark when I got there. The narrow dirty streets looked so lonely that I was frightened, and made my way as quickly as possible to Westminster Bridge, and so home.

“On Wednesday I went for my botany prize-books from the university, and was very much pleased by their handsome appearance. Regnault's Chimie I have been reading a good deal lately, and I have nearly been through the first volume; but I hardly like it as much as I expected, as it is chiefly on the practical, not the theoretical part.

“Sunday, 16th January 1853.—Christmas and the Christmas holidays have passed since my last date, and I am again settled down for three months', perhaps six or seven months' hard work. The last lectures at college were on Thursday, 23d December, and on Friday morning at half past six I left for home with Harry, who was going to stay a week or two with the Booths. I got home to dinner, and found everything as usual, except that there was Herbert in addition. Lately, I have found myself thinking more and more of home, and now it is settled that this is to be my last half year in London, I think more of it than ever, and feel a kind of anxiety that the time may pass as quickly as possible, and that there may be no alterations of any kind in that home. My wish to be at or near home has been one of my reasons for choosing a common business in preference to any profession or other occupation, and I have felt as if it savoured of selfishness to leave home altogether and go and take care of your own interests at some place a long way off.

“It is now, however, settled finally, I hope, in my own mind as well as in papa's and Lucy's, that I am to go into some office at Liverpool. I have had doubts whether it will not be exceedingly difficult for me to acquire ready business habits, but I think that after setting my mind upon it for a

Edition: orig; Page: [28]

year before, I shall have sufficient determination to do it. In every other respect I believe that my two years' colleging in London will be a great advantage even in business. One necessary will be that I should not think of my business in the day-time and my work at night as on an equality, but the latter as altogether subordinate, at least for a long time; not that I think it actually of less importance to success. My plan of work, as far as I have thought of it as yet, will be this: for the rest of this session I will give almost all my attention to the following, and in the order in which they are mentioned:—mathematics, chemistry, natural philosophy, botany, crystallography or mineralogy. For several of the first years that I shall be at home I shall also give most of my leisure time to science, because I know that to do a thing well the mind should be engaged with it as singly as possible, that is to say, when you are thinking much about such things as the theory of equations, diffusion, the atomic theory, relation of the forces, etc., the mind cannot take such interest in, and therefore cannot so well learn, history, or Latin and Greek. The case is quite different, I believe, when you are working for prizes or a degree, and not for the sake of the knowledge.

“I shall, however, as soon as I am at home, begin to work a little at French or German, and I shall, of course, read more novels and common books than I do now. I shall also amuse myself down in the cellar with chemical experiments, making instruments; which, however, I think are not altogether useless amusements. After those years are past, and when I shall be a man at twenty-two or twenty-three, I shall make a gradual transition to literary studies, and especially history, though always keeping up my scientific knowledge a little. I don't know how far I shall be able to learn any mathematics by myself.

“So much for all my grand schemes and anticipations, which will be upset most likely some fine day. I passed the Christmas holidays better perhaps than most of my holidays on former occasions, but perhaps because there was not time to get into my usual lazy way. We had the usual Christmas dinner at our house. During the next week I set my bench in order and began my ‘reflective goniometer,’ which

Edition: orig; Page: [29]

I had had in my head for some time. I made it entirely of soft mahogany, zinc plate, and a few brass screws, but it has succeeded, and is correct, I believe, to the tenth of a degree. I had nearly knocked under to making and graduating the dial, and I did not finish it till the last day of the holidays.

“I played the organ a good deal, especially out of the Messiah. The New Year's Day dinner at St. James' Road was decidedly pleasant, and well finished up by a good game at blind man's buff. Almost every party I go to makes me like dancing parties worse, but other ones rather better, so I think I shall never be a dancer. I spent a part of two evenings in looking over half of Mr. Archer's collection, and I saw Philips, the great mineralogist, at the Medical Institution. I also bought three shillings and sixpence worth of minerals from Wright, chiefly forms of carbonate of lime.

“Sunday, 23d January.—Since I came to London at the beginning of this term I have chiefly kept to my work, and have therefore little worth putting down. I have been twice to the British Museum, and find I can take as much interest in the sculptures and other antiquities as the minerals, etc.

“I have been wanting very much to get Mayhew's London Labour and London Poor, as that is the only book I know of to learn a little about the real condition of the poor in London. I managed to root out a dozen of the numbers in rather a dirty condition in a shop in Holywell Street, and yesterday I bought them at a penny a piece. They will lead, I expect, to a few walks this term.

“Last Friday I had a great treat in attending one of Faraday's Friday evening lectures at the Royal Institution. … As to college affairs, I am going on steadily and just as usual. In mathematics we are just beginning the theory of equations, and during the last week have got through Descartes', Fourier's, and Sturm's theorems of the limits of the roots of equations. They are the most truly difficult things we have come to, and I do not thoroughly understand them yet.

“It is only about two months to the chemistry examination, and I am beginning to think seriously of it. The best way to learn the metals thoroughly I think to be to make a large table containing the composition, preparation, crystalline

Edition: orig; Page: [30]

form, etc., of each metallic compound. I began the table last night. (It turned out a failure.) I have been reading a good deal of Regnault's Chimie, and a little of Daniell's Introduction to Chemical Philosophy, which, however, I think a poor book.

“In the chemistry class we have only just begun the metals, as we are very late; we are to do the metals and the organic together, which I do not think a good way. Before the examination I shall read most of Graham, some of Liebig's Letters, work at parts in Gmelin's Handbook, read a good deal of Regnault, etc.

“In Potter's class of natural philosophy we have been engaged since the beginning of the term with electricity. He does the experiments magnificently, but gives us a minimum of all theory, which consequently I have to read for myself. I must read and work an awful deal for this class after Easter.

“I now and then read a little of Schmitz's Greece, but I get on very slowly, and shall not go into the examination.

“Sunday, 30th January.—On Friday night I was again at a lecture at the Royal Institution by Dr. Williamson. The title was ‘On some recent Discoveries in Organic Chemistry.’ At college we have been doing very hard things in the theory of equations, which puzzle me awfully. In natural philosophy we have finished electricity and begun voltaic electricity. I have nearly finished reading electricity in Library of Useful Knowledge, am half through Sir Snow Harris' Electricity, and am at the same time reading in chemistry two volumes of Regnault, Liebig's Letters, now and then a little of Graham, Schmitz's Greece, etc., more than I have read for a long time.

“Sunday, 27th February.—I have now a whole month to make up, although several important things have happened, which I ought to have put down long since, and would have done perhaps, if my last one or two Sundays had not been rather engaged.

“Soon after the beginning of this month we heard that my uncle, F. Hornblower, was very ill of rheumatic fever, and as he had for some time been very poorly and weak, it was considered dangerous. In a day or two he died, from

Edition: orig; Page: [31]

the complaint reaching the heart. This news was particularly sad on poor Aunt Jane's account. His funeral was from our house at Liverpool. Aunt Jane has been living there ever since, and I should think will continue to do so as long as she lives. I have known Uncle Hornblower better than any of my uncles, almost as much more as I have known Aunt Jane better than any of my aunts, and he has always been particularly kind to me. Several years ago (I think about five or six) I used to dine every day at his house in Falkner Street, at the opposite corner to our present house, while I was at the Mechanics' Institution. Since that I have spent many weeks at his house at Nantwich, which have always been very pleasant ones. The last time was in October.

“About the middle of the month I received from papa one of his business-like letters, which I like to get better than any others, on the important subject of ‘What I am going to be,’ as the phrase is. I had before made up my mind to be in some commercial business, but in this letter he advised me to choose some one which I should be more able to like for itself, and proposed the iron trade. This letter, of course, set me to think very seriously, as now one of the greatest questions of my life was to be settled once for all. I had before thought of some of the reasons which he gave, and having had the same advice from several other people, I was not long in fixing to be a manufacturer of some sort, putting, however, an ironmaster's business out of the question, because it would not suit me at all well, and would, besides, take me from home for the rest of my life. Now, however, I have the great pleasure of thinking that, as far as can be known at present, it is determined I shall not be away from home more than six or seven months longer. It can hardly be conceived, I think, how many pleasures, and still more how many real advantages, I should have lost by leaving or, I may say, losing my home at once. The choice now is between a sugar refinery and a soap, chemical, or some other sort of manufactory, and an indispensable condition is that it be in Liverpool. I shall probably go into the Birkbeck Laboratory next term.

“About a week ago there was a rather hard frost, and

Edition: orig; Page: [32]

skating began vigorously as soon as the ice bore. On Saturday, 19th, I skated for two hours on Regent's Park, where the ice, however, was very bad, and in the afternoon for about two more on the Serpentine. At the latter place I enjoyed it especially, as, besides plenty of tolerably good ice, there were crowds of people everywhere, which always, I think, increases the fun, and the excitement now and then of somebody falling in and getting saved by the Royal Humane Society's men. On Sunday I went with Harry to some ice near the railway station at Barnes, where we skated for some time. The Monday before last we had some capital fun at college with snowballs, chiefly in the storming of the portico, which was defended by another party of the students. The medicals had a fight in the streets with blackguards, which ended in rather a serious row.

“On Friday, 18th, I went over a lucifer match manufactory, which I thought very well worth seeing, though it was a dirty low hole. Harry wanted some specimens of matches in different stages for a lecture which he gave last Monday at the Spicer Street Domestic Mission, ‘On the Use and Importance of Chemistry, illustrated by the improvements it has produced in lucifer matches, bleaching, and other things.’

“I have got into a rather lazy way of working lately, partly, I think, on account of the skating, etc., but am going to set to work seriously for the chemical examination, which is only a month off; we are now going through the organic and the metals at the same time, on different days of the week, and get on very well. I had hoped that when we began algebraical geometry, as we have done now, we should have had a little rest in mathematics, but the exercises seem only to get harder and harder. The natural philosophy also is very dull, being on hydrostatics, and, worst of all, the history class begins to-morrow morning at eight o'clock.

“I have been one or two good walks lately, chiefly among the manufacturing parts. One Saturday I went from Waterloo Bridge eastwards along the wharfs on the Surrey side, as far as Jacob's Island, which I found much improved since I visited it about a year since. The ditches had been filled up or arched over, and the streets were

Edition: orig; Page: [33]

beginning to be filled. Another Saturday I started from the same place, but travelled west as far as Vauxhall Bridge, where I again crossed the river, and proceeded again in the same direction nearly to Chelsea, whence I walked straight home. Belvedere Road is full of small wharfs and manufactories, such as drain tile potteries, gas-works, slate-works, bone-mills, glue, whiting, etc., manufactories. Yesterday afternoon I accomplished still more. Starting from college a little after two, I walked through the city and along White chapel and the Commercial Road almost to the West India Docks. I then turned up, and passing a good many manufactories, reached Bow and got home by railway. I feel as if I could see nothing with so much pleasure now as a dirty pearl ash manufactory or tar distillery. I have remarked that in Bermondsey, Tower Hamlets, and most of the parts east of London Bridge, the streets are wide and open—showing, I suppose, that land is cheap—but that the houses are very low, not always unhealthy or dirty, seldom more than two low stories in height. These parts are very low and wretched, but are not, as far as I could see in the day-time, half so full of busy vice and crime as St. Giles, Drury Lane, etc.

“Sunday, 3d April.—On the 12th March I had a pleasant walk from London Bridge through the close parts of Bermondsey and among the tanneries, till I came into the middle of the market gardens. I went down Blue Anchor Road, and returned up the Deptford Road to the Thames Tunnel, whence I came home by the railway.

“Before Easter we were going through the conic sections in the mathematical class, and I kept up pretty well in them till near the end, when I partly left off working at mathematics that I might have more time for chemistry. In natural philosophy we went at a great rate through pneumatics, the air-pump, the steam engine, heat, and part of acoustics, to none of which I attended much, except the last, for which I am reading a little.

“A few weeks before Easter I got a letter from papa with some money, and asking me to go to Liverpool for the Easter holidays. I was very much astonished at it, but of course said immediately that I would, though I should not have more than a week.

Edition: orig; Page: [34]

“Thursday, the day before Good Friday, was the first day of the holidays, so on that day I went down. I had a comfortable journey, reading all the way nearly the whole of ‘Les Corps Gras,’ in Regnault. I did not find the house turned so much topsy-turvy by Aunt Jane's illness as I had expected, and everything seemed as cheerful as usual. I soon found, however, that music was not allowed, and, in fact, neither the organ nor the piano were opened all the time I was in Liverpool.

“The greater part of the first morning I spent in a walk with Tommy at Birkenhead, but I began a few chemicals, practising a little at crystallising on nitre. On Saturday morning I went with papa to call on a Mr. Nevin, the manager of Steele's Soap Works in Sir Thomas Buildings. Papa had seen a letter of his in the newspaper on penal jurisprudence, so he sent him one of his books, and getting to know his address, called on him. Sunday morning to chapel, and the rest of the day at chemicals.

“On Monday morning Willy Jevons and I went over the soap-works with papa. On Tuesday morning I went over an iron shipbuilding yard at Birkenhead with Willy and Uncle Timothy. The punching and shearing were neatly done, but the carpentering machines were not at work. Mr. Steele's head clerk, Mr. Nevin, had given me a letter to see a soda-works of his at Prestatyn near Rhyl, and on Wednesday papa and I went to see them, and it was fixed that I should go straight to London from Chester. We crossed to Birkenhead by the 9.45 boat, and got to Prestatyn about one, going by railway to Chester, and from there by the Chester and Holyhead Railway along the Wales shore of the Dee. We saw over the works very completely, and I got specimens of the materials and the soda ash in different steps of the process. The process was almost the same as I had learnt it from Graham, but the only way to gain a good idea of the manufacture is to see it. After dinner we returned to Chester by the railway, and papa there left me, while I went on at six to Crewe, passing Beeston Castle and the Nantwich station. From Crewe to Birmingham I went by the South Staffordshire Railway, except between Crewe and Stafford, passing through the

Edition: orig; Page: [35]

middle of the iron district, where there were numberless iron furnaces, two or three together, blazing away on either side of the railway, and lighting up the sky; this part of the journey was long and troublesome, but pleasant, because it was new to me. Getting to Birmingham after ten, I found that the train for London started from another station, and I was perhaps nearly an hour walking about the streets (which did not appear to me at all fine) to find it. I then exceedingly enjoyed some tea and ham at a coffee-house I found open, and set off for London at 12.15, getting home without further trouble at about five in the morning, having been out quite eighteen hours, the greater part too on the railway.

“Till the next Tuesday I had none but the chemistry class to attend, and I had then great doubts whether I should go into the chemistry examination or not. At last I resolved I would make an effort and go in, come what would, and the result was that I answered the eleven questions in eight hours, quite, I believe, to my own satisfaction, but I do not yet know how much to the satisfaction of Graham.

“The next day I entered the laboratory, to which I had been looking forward some time, but I did scarcely anything the first day but get my apparatus, clean my bottles, and arrange my bench. The next day I was set to try the reactions of antimony, tin, and arsenic; and after being a few days over these I had to separate them from a common solution, which I found a long and troublesome process. One day, while making arseniuretted hydrogen, I suppose I breathed a little, for I was ill and sick after it—a real case of poisoning by arsenic. After this I began the regular course of analysis, which I found far better, having merely to find out the salt in a particular solution, and then try its reactions.

“I expected Potter's class would be better when on Light, but it is duller than ever. In mathematics we are just beginning the differential calculus, at which I am going to work very hard at nights. I am seriously thinking of making an effort for both the natural philosophy and mathematical examinations, seeing how well that for the

Edition: orig; Page: [36]

chemistry succeeded; but I have very little time to work, and can only expect a low certificate in the latter class.

“I took my first proper botanical walk yesterday in some fields at Hampstead, where I got four ranunculaceœ, primroses, and a specimen of daisy. I have bought a map of the environs fifteen miles round London, which distance only I intend to be the limit of my numerous projected excursions this summer.”

There is no further entry in his journal until the 29th January 1854, when he writes: “From several causes, among which laziness, business, and the want of the book, are some, I have not written a word since last April. I must now therefore give a history of these last nine or ten months, about which I can perhaps remember now as much as I shall ever want to read again.

“During the last two months at college I attended chiefly of course to the laboratory, though working at Potter's and trying to keep up in De Morgan's. With analysis, as has always happened to me in practical chemistry, I did not succeed quite so well as I might have done, much to my own disappointment, and I had regular periods of disgust with the laboratory. I got through (rather slowly, however) nearly all the ‘bottles’ and did several quantitatives, which were neither very bad nor very good, which with a few preparations was all my work. But I consoled myself with thinking that it was the first three months I had learned [in the laboratory].

“I worked up well for Potter's examination, not keeping merely to what was sufficient to get the prize; and having De la Rue's electricity, I learned much more on that subject than was necessary. I had no difficulty with the mechanics, sound, light, electricity, except a little I missed in hydrostatics and a mistake or two about telescopes, but was not so much up in astronomy—a newer subject to me. On waves I answered a good deal. Mathematics was a much harder affair, of course. Some time before the examination I formed some desperate resolutions as to the place I would get, and I did work up a little. I tried very hard in the examination, but spent too much time on the hard ones, and came out fourth. Since Easter I had been thinking a great

Edition: orig; Page: [37]

deal of again living at home, and looked forward to it as a great happiness.