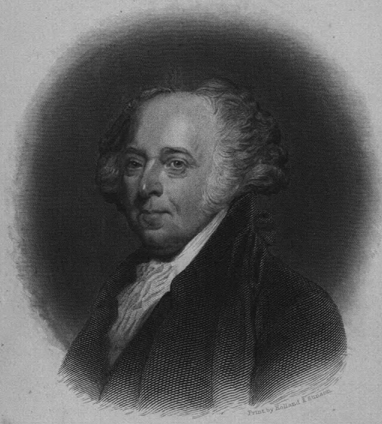

THE LIFE OF JOHN ADAMS.

Edition: current; Page: [2]

Edition: current; Page: [3]

PRELIMINARY.

RESPECTING THE FAMILY OF ADAMS.

The first charter of the Colony of Massachusetts Bay was granted by Charles the First, and bears date the 4th of March, in the fourth year of his reign, 1629. It recites letters-patent of James the First, dated 3 November, in the eighteenth year of his reign, 1620, granting to the Council established at Plymouth, in the county of Devon, for the planting, ruling, ordering, and governing of New England, in America, all that part of America, from latitude 40° to 48°, and through the main lands from sea to sea. Then, that the Plymouth Council, by deed indented 19 March, 1628, conveyed to Sir Henry Rosewell, Sir John Young, knights, Thomas Southcott, John Humphrey, John Endicott, and Symon Whetcomb, their heirs and associates forever, all that part of New England, lying between three miles south of Charles, and three miles north of Merrimack rivers. Charles, therefore, at the petition of the grantees, and of others whom they had associated unto them, grants to them the same lands, and constitutes them a body corporate politique, in fact and name, by the name of the Governor and Companie of the Massachusetts Bay in New England.

Among the grantees of this charter is a person by the name of Thomas Adams.

Hutchinson says that the day for the annual election of officers, by charter, was the last Wednesday in Easter Term, and that on the 13th of May, 1628, Cradock was chosen governor, Goffe, deputy-governor, and eighteen assistants; of whom Thomas Adams was the twelfth.

Edition: current; Page: [4]

That on the 20th of October, 1629, a new choice of officers was made, consisting of such persons as had been resolved on the 29th of August preceding. John Winthrop was elected governor, John Humphrey, deputy-governor, and eighteen assistants; of whom Thomas Adams was the last.

From this, it appears that Thomas Adams was one of those who had determined to come over with the charter. But nothing further has been found concerning him.

Hutchinson says that, in 1625, one Captain Wollaston, with about thirty persons, began a plantation near Weston’s, which had been abandoned; that no mention is made of a patent to Wollaston; that Morton changed the name of Mount Wollaston to Merry Mount; and that the people of Plymouth seized him, to send him to England.

Winthrop’s Journal, under date of 20 September, 1630, says: “Thomas Morton was adjudged to be imprisoned till he were sent into England, and his house burnt down, for his many injuries offered to the Indians, and other misdemeanors.”

Winthrop’s Journal, 17 September, 1639: “Mount Wollaston had been formerly laid to Boston; but many poor men having lots assigned them there, and not able to use those lands and dwell still in Boston, they petitioned the town, first, to have a minister there, and, after, to have leave to gather a church there, which the town, at length, upon some small composition, gave way unto. So this day they gathered a church after the Edition: current; Page: [5] usual manner, and chose one Mr. Tompson, a very gracious, sincere man, and Mr. Flint, a godly man also, their ministers.”

“There was a church gathered at the Mount, and Mr. Tompson, a very holy man, who had been an instrument of much good at Acamenticus, was ordained the pastor the 19th of the 9th month.”

It was in 1634 that Mount Wollaston had been laid to Boston, and Winthrop’s Journal says that on the 11th of December, 1634, the inhabitants of Boston met after the lecture, and chose seven men who should divide the town lands among them.

At a general court held at Newton, 3 September, 1634, it is ordered that Boston shall have enlargement at Mount Wollaston and Rumney Marsh. The bounds were settled 13 April, 1636.

“At a general court of elections, held at Boston, 13 May, 1640. The petition of the inhabitants of Mount Wollaston was voted, and granted them to be a town, according to the agreement with Boston, and the town is to be called Braintree.”

Thus it appears that Morton’s settlement at Mount Wollaston was broken up and his house was burnt in 1630, the year in which Winthrop and his colony arrived; that in 1634 the General Court at Newton granted enlargement to the town of Boston at Mount Wollaston; that in 1636 grants of land were made by the inhabitants of Boston to individuals to make settlements there without removing from Boston; that many of the poor men who had lots assigned them, could not use them, and continue to reside in Boston; that they therefore petitioned Boston, first, to have a minister, and, afterwards, to gather a church, which leave was accordingly granted. They chose Mr. Tompson and Mr. Flint their ministers. Mr. Tompson was ordained the 19th of November, 1639; and on the 13th of May, 1640, they were by the court of elections made a town, by the name of Braintree.

Among the grantees of these lands was Henry Adams, probably Edition: current; Page: [6] a brother of Thomas Adams, one of the grantees of the charter, and one of the Assistants chosen at the time of its transfer to this country.

By the records of the town of Braintree, it appears that this Henry Adams was buried on the 8th of October, 1646. From his will, it appears that he left a widow, five sons, named Peter, John, Joseph, Edward, and Samuel, and a daughter Ursula. He had three other sons, not mentioned in the will, whose names were Henry, Thomas, and Jonathan.

Henry was the eldest son, and was the first town-clerk of Edition: current; Page: [7] Braintree. The records of births, marriages, and deaths, in the first book of Braintree town records, are in his handwriting; and the first marriage recorded is his own with Elizabeth Payne, 17 October, 1643.

The second is that of Joseph Adams and Abigail Baxter, married the 26th of November, 1650. The gravestones of this Joseph Adams and of his wife are yet extant in the burial-ground of the Congregational Church at Quincy, and the inscriptions on them show that he died on the 6th of December, 1694, in the 68th year of his age. He was, therefore, born in the year 1626, in England, four years before the emigration of the Winthrop colony; and there is reason to believe that he was the youngest, and that Henry was the eldest of the sons of the first Henry, who came with him from England.

On the same book of records are entered the births of three children of Henry and Elizabeth Adams.

Eleazar, born 5 August, 1644. Jasper, born 23 June, 1647. And Elizabeth, born 11 November, 1649.

About that time, this Henry Adams removed to Medfield, of which he was also the first town-clerk, and where numerous descendants of his name are yet remaining. Among them is the distinguished female historian, Hannah Adams. He died on the 21st February, 1675, at the age of 71. He was, therefore, born in the year 1604, was 26 years of age at the time of the emigration, 36 when Braintree was made a town, and 39 when married to Elizabeth Payne.

Of the sons of the first Henry Adams, Peter and Joseph only remained settled for life at Braintree. Joseph and his wife lived together forty-two years; as the inscription on her gravestone shows that she died on the 27th of August, 1692, only two years before her husband.

Their children, as recorded upon the town book, were:—

Hannah, born 13 November, 1652. Joseph, born 24 December, 1654. John, born 15 February, 1656. Abigail, born 27 February, 1658. John and Bethiah, born 20 December, 1660. Mary, born 8 September, 1663. Samuel, born 3 September, 1665. Another Mary, born 25 February, 1667. Peter, born 7 February, 1669. Jonathan, born 31 January, 1671. Mehitable, born in 1673.

Of the original military establishment at Braintree, it appears, Edition: current; Page: [8] from a minute on the record book, apparently made by John Mills, when he was the town-clerk, for it is professedly made from the memory of the writer—that Henry, Thomas, and Peter Adams were sergeants of companies, and John and Joseph Adams, drummers.

The inventory of the goods movable and immovable of the first Henry Adams presents a property, the sum total of which is seventy-five pounds thirteen shillings—the real and personal estate being nearly of equal value. It includes a house, barn, and ground around them. Three beds and their bedding, one of which was in the parlor, and two in the chamber. A variety of farming utensils and kitchen furniture; some store of corn, hay, and hops; one cow and a heifer, swine, and one silver spoon, and some old books. There was land which he held upon lease or temporary grant from the town; and he bequeathes the remainder of his term to his sons, Peter and John, and his daughter Ursula. He orders his books to be divided among all his children. The house and lands belonging to himself he leaves to his wife during her life or widowhood, and afterwards to his sons, Joseph and Edward, and his daughter, Ursula, charged with a payment to his son, Samuel, for land purchased of him, to be paid for in convenient time. There was a discretionary power to the wife to make use, by way of sale, of part of the land, in case of urgent need.

There is no notice in the will of the sons Henry, Thomas, or Jonathan, although they still resided at Braintree. They were, doubtless, otherwise well provided for. The will discovers a spirit of justice in the distribution, and of parental and conjugal affection. The land purchased of Samuel to be paid for in convenient time; the charge upon the children, to whom the reversion of the land is given, to pay for it; and, above all, the discretionary and contingent power to the wife to sell, are incidents truly affecting.

At the decease of this first Henry, his son, Joseph, was but twenty years of age. He lived nearly half a century after—reared, as we have seen, a numerous family of sons and daughters, and at his decease left his estate to his sons, Joseph, John, Edition: current; Page: [9] and Peter, and to his daughters, Hannah Savil, Abigail Bass, Bethiah Webb, Mary Bass, and Mehitable Adams. Four of the daughters were married before the testator’s death; Mehitable shortly afterwards, 21 July, 1697, married Thomas White.

The bulk of the estate, consisting of a malt-house and brewery with lands, malting tools and vessels, was given to Peter, the youngest son, who was also made sole executor of the will.

Joseph Adams, senior, was, on the 10th of April, 1673, chosen a selectman of the town of Braintree, together with Edmund Quincy; and, in 1692-93, the same Joseph Adams was chosen surveyor of highways.

His son, Joseph Adams, junior, was born, as we have seen, 24 December, 1654. He died 12 February, 1737, at the age of 82. He had three wives.

First, Mary Chapin, 1682, by whom he had

Mary, born 6 February, 1683, married Ephraim Jones.

Abigail, born 17 February, 1684, married Seth Chapin.

She died 14 June, 1687.

His second wife was Hannah Bass, daughter of John and Ruth Bass, a daughter of John Alden.

The issue of this marriage were

Joseph, born 4 January, 1689, who was minister at Newington, New Hampshire. John, born 28 January, 1691, died 25 May, 1761. Samuel, born 28 January, 1693. Josiah, born 18 February, 1696, died 20 January, 1722. Hannah, born 23 February, 1698, married Benjamin Owen, 4 February, 1725. Ruth, born 21 March, 1700, married Nathan Webb, 23 November, 1731. Bethiah, born 13 June, 1702, married Ebenezer Hunt, 28 April, 1737. Ebenezer, born 30 December, 1704.

Hannah (Bass) Adams, died 24 October, 1705.

The third wife of Joseph Adams, junior, was Elizabeth [Editor: missing word]

They had one son, Caleb, born 26 May, 1710, who died the 4th of June following.

Elizabeth survived her husband, and died February, 1739.

Joseph Adams, junior, or the second, made his will on the 23d of July, 1731.

Edition: current; Page: [10]

He had given his eldest son, Joseph, the third of the name, a liberal education, that is to say, at Harvard College, where he was graduated in 1710; and considering that as equivalent to his portion of the paternal estate, he gave him, by will, only five pounds to be paid in money by his executors within one year after his decease. He distributed his estate between his sons, John, Samuel, Josiah, and Ebenezer, leaving legacies to his daughters.

Mary Jones, fifteen pounds. The three children of Abigail Chapin, of Mendon, six pounds. Hannah Owen, fifteen pounds. Ruth Adams, eighty pounds. Bethiah Adams, eighty pounds.

On the 7th of March, 1699, this Joseph Adams was chosen a selectman of Braintree, and on the 4th of March, 1700, a constable. His eldest son, Joseph Adams, on the same year that he was graduated, 1710, was chosen the schoolmaster.

The lives of the first and second Joseph Adams comprise a period of one hundred and ten years, in which are included the whole of the first century of the Massachusetts Colony, and seven years of the second. The father and son had each twelve children, of whom, besides those that died in infancy or unmarried, the elder left three sons and five daughters living at his decease; and the younger, five sons and four daughters, besides three grandchildren, offspring of a daughter who died before him. The daughters of the father and son were all reputably married, and their descendants, by the names of Savil, Bass, Webb, White, Chapin, Jones, Owen, Hunt, and numberless others, are scattered throughout every part of New England.

The inventory of the first Henry Adams displays no superfluity of wealth. He had, indeed, a house and land to bequeathe, but the house consisted of a kitchen, a parlor, and one chamber. Dr. Franklin has recorded, in the narrative of his life, the period of his prosperity, when his wife decided that it was time for him to indulge himself at his breakfast with a silver spoon; and this is the identical and only article of luxury found in the inventory of the first Henry Adams.

But he had raised a family of children, and had bred them to useful vocations and to habits of industry and frugality. His eldest son, Henry, was the first town-clerk, first of Braintree, Edition: current; Page: [11] and then of Medfield. His sons, Thomas and Samuel, were among the first settlers of Chelmsford, and of Mendon.

The brewery was probably commenced by the first Henry. It was continued by his son, Joseph, and formed the business of his life. At the age of twenty-four he married a wife of sixteen, and at his decease, after a lapse of more than forty years, left the malting establishment to his youngest son. His other children, with the exception of his youngest daughter, being all comfortably settled.

This daughter (Mehitable) was only twenty-one years of age at the time of her father’s death, and by his will he provided that she should, while she remained unmarried, live in the house which he bequeathed to his son, Peter. About three years after her father’s death, she married Thomas White.

The estate left by the first Joseph Adams was much more considerable than that which had been left by his father; but was still very small. To his eldest son, Joseph, he bequeathed only one acre of salt meadow. Joseph had already been many years settled; had been twice married, and was father of four children at the time of his father’s decease. In a country rate, made by the selectmen of the town of Braintree, on the 12th of May, 1690, Joseph Adams, senior, was assessed £1. 19. 6, and Joseph Adams, junior, £1. 4. The prosperity of the family was still increasing. And it still continued, so that this second Joseph was enabled to defray the expense of educating his eldest son, of the same name, at college. The effect of this college education, however, was to withdraw the third Joseph from the town. He became a preacher of the gospel, and was settled at Newington, in New Hampshire, for sixty-eight years, and there died in the year 1783, at ninety-three years of age.

John Adams was the second son of the second Joseph. He was born the 28th of January, 1691; so shortly before the death of his grandfather, the first Joseph, that although he had, doubtless, in childhood seen him, he could certainly have retained no remembrance of him. The lives of this John Adams and of his son, who bore his name, comprise a period of no less than one Edition: current; Page: [12] hundred and thirty-six years, from 1691 to 1826, including forty years of the first and within four years of the whole of the second century of the Massachusetts colony. The two Josephs, father and son, may thus be considered as representing the first century of the Massachusetts Colony, and the two Johns, father and son, of the second.

On the 31st of October, 1734, the first John Adams was married to Susanna Boylston, daughter of Peter Boylston, of Brookline. The issue of this marriage were

John Adams, born 19 October, 1735. Peter Boylston, born 16 October, 1738. Elihu, born 29 May, 1741.

John Adams, following the example of his father, gave his eldest son the benefit of an education at Harvard College; for which he was prepared, under the instruction, successively, of Mr. Joseph Marsh, the minister of the first Congregational parish of Braintree, and of Joseph Cleverly, who was some time reader of the Episcopal Church at the same place.

The elder John Adams was many years Deacon of the first church in Braintree, and several years a selectman of the town.

Edition: current; Page: [13]

CHAPTER I.: Education of Mr. Adams—School at Worcester—Choice of a Profession.

In tracing the short and simple annals of the paternal ancestors of John Adams, from their establishment here with the first settlers of the country, we have found them all in that humble, but respectable condition of life, which is favorable to the exercise of virtue, but in which they could attract little of the attention of their contemporaries, and could leave no memorial of their existence to posterity. Three long successive generations and more than a century of time passed away, during which Gray’s Elegy in the country churchyard relates the whole substance of their history. They led laborious, useful, and honest lives; never elevated above the necessity of supporting themselves by the sweat of their brow, never depressed to a state of dependence or want. To that condition, John Adams himself was born; and when the first of British lyric poets wrote,—

- “Some village-Hampden, that, with dauntless breast,

- The little tyrant of his fields withstood;

- Some mute inglorious Milton here may rest,

- Some Cromwell guiltless of his country’s blood,”

he little imagined that there was then living, in a remote and obscure appendage of the British dominions, a boy, at the threshold of Harvard College, whose life was destined to prove the prophetic inspiration of his verse.

It is in the order of the dispensations of Providence to adapt the characters of men to the times in which they live. The grandfather of John Adams had given to the eldest of his twelve children a college education for his only inheritance. And a precious inheritance it was; it made him for nearly seventy years an instructor of religion and virtue. And such was the anticipation and the design of the father of John Adams, who, Edition: current; Page: [14] not without some urgent advice and even solicitation, prevailed upon his son to prepare himself for college. He was there distinguished as a scholar, in a class which, in proportion to its numbers, contained as many men afterwards eminent in the civil and ecclesiastical departments, as any class that ever was graduated at that institution. Among them were William Browne, subsequently Governor of the Island of Bermuda; John Wentworth, Governor of New Hampshire, before the Revolution, and afterwards Lieutenant-Governor of Nova Scotia; David Sewall, long known as Judge of the District Court of the United States in Maine; Tristram Dalton, one of the first Senators of the United States from Massachusetts; Samuel Locke, some time President of the College; and Moses Hemmenway, who attained distinction as a divine. Adams, Hemmenway, and Locke had, even while undergraduates, the reputation of being the first scholars in the class.

In the ordinary intercourse of society, as it existed at that time in New England, the effect of a college education was to introduce a youth of the condition of John Adams into a different class of familiar acquaintance from that of his fathers. The distinction of ranks was observed with such punctilious nicety, that, in the arrangement of the members of every class, precedence was assigned to every individual according to the dignity of his birth, or to the rank of his parents. John Adams was thus placed the fourteenth in a class of twenty-four, a station for which he was probably indebted rather to the standing of his maternal family than to that of his father. This custom continued until the class which entered in 1769, and was graduated in 1773; and the substitution of the alphabetical order, in the names and places of the members of each class, may be considered as a pregnant indication of the republican principles, which were rising to an ascendency over those which had prevailed during the colonial state of the country.

- “Orders and degrees

- Jar not with liberty, but well consist.”

So said the stern republican, John Milton, who, in all his works, displays a profound and anxious sense of the importance of just subordination.

Another effect of a college education was to disqualify the Edition: current; Page: [15] receiver of it for those occupations and habits of life from which his fathers had derived their support. The tillage of the ground, and the labor of the hands in a mechanical trade, are not only unsuited to the mind of a youth whose pubescent years have been devoted to study, but the body becomes incapacitated for the toil appropriate to them. The plough, the spade, and the scythe are instruments too unwieldy for the management of men whose days have been absorbed in the study of languages, of metaphysics, and of rhetoric. The exercises of the mind and memory take place of those of the hand, and the young man issued from the college to the world, as a master of arts, finds himself destitute of all those which are accomplished by the labor of the hands. His only resources are the liberal professions—law, physic, or divinity, or that of becoming himself an instructor of youth. But the professions cannot be assumed immediately upon issuing from college. They require years of further preparatory study, for qualification to enter upon the discharge of their duties. The only employment, then, which furnishes the immediate means of subsistence for a graduate of Harvard College, is that of keeping a school.

There is nothing which so clearly marks the distinguishing character of the Puritan founders of New England as their institutions for the education of youth. It was in universities that the Reformation took its rise. Wickliffe, John Huss, Jerome of Prague, and Luther, all promulgated their doctrines first from the bosom of universities. The question between the Church of Rome and all the reformers, was essentially a question between liberty and power; between submission to the dictates of other men and the free exercise of individual faculties. Universities were institutions of Christianity, the original idea of which may, perhaps, have been adopted from the schools of the Grecian sophists and philosophers, but which were essential improvements upon them. The authority of the Church of Rome is founded upon the abstract principle of power. The Reformation, in all its modifications, was founded upon the principle of liberty. Yet the Church of Rome, claiming for her children the implicit submission of faith to the decrees of her councils, and sometimes to the Bishop of Rome, as the successor of Saint Peter, is yet compelled to rest upon human reason for the foundation of faith itself. And the Protestant churches, while vindicating Edition: current; Page: [16] the freedom of the human mind, and acknowledging the Scriptures alone as the rule of faith, still universally recur to human authority for prescribing bounds to that freedom. It was in universities only that this contentious question between liberty and power could be debated and scrutinized in all its bearings upon human agency. It enters into the profoundest recesses of metaphysical science; it mingles itself with the most important principles of morals. Now the morals and the metaphysics of the universities were formed from the school of Aristotle, the citizen of a Grecian republic, and, perhaps, the acutest intellect that ever appeared in the form of man. In that school, it was not difficult to find a syllogism competent to demolish all human authority, usurping the power to prescribe articles of religious faith, but not to erect a substitute for human authority in the mind of every individual. The principal achievement of the reformers, therefore, was to substitute one form of human authority for another; and the followers of Luther, of Calvin, of John Knox, and of Cranmer, while renouncing and denouncing the supremacy of the Romish Church and the Pope, terminated their labors in the establishment of other supremacies in its stead.

Of all the Protestant reformers, the Church of England was that which departed the least from the principles, and retained the most of the practices, of the Church of Rome. The government of the State constantly usurped to itself all the powers which it could wrest from the successor of St. Peter. The King was substituted for the Pope as head of the church, and the Parliament undertook to perform the office of the ecclesiastical councils, in regulating the faith of the people. Even to this day the British Parliament pretend to the right, and exercise the power, of prescribing to British subjects their religion; and, however unreasonable it may be, it is impossible to discard all human authority in the formation of religious belief. Faith itself, as defined by St. Paul, is “the substance of things hoped for, the evidence of things not seen.” But without an express revelation from Heaven, the formation of this hope, and the belief in the existence of this evidence, come not from the internal operations of the mind, but by tradition from others, by the authority of instruction. To deny, therefore, all human authority, in matters of religion, is to assert an abstract principle Edition: current; Page: [17] to which human practice cannot conform. Equally impracticable is it to control, by authority, the exercise of the faculties of the mind; and it is in universities, at the fountains of human knowledge, that the freedom of the mind has the most extensive range for operation. In England, the progress of the Reformation was continually entangled, not only with the affairs of the state, but with the passions and the caprices of the sovereign. When Luther first planted the standard of reformation at the University of Wittenberg, Henry the Eighth, uniting in himself the character of a dogmatist and a tyrant, published a book against him and his doctrines, from which he and all his successors have derived, from the pious gratitude of Leo the Tenth, the title of Defenders of the Faith; but when, losing his affection for his wife, he became enamoured with one of her maids of honor, he quickly learned from his angelic doctor, Thomas Aquinas, that the infallibility of the Pope could not legitimate his marriage with his brother’s widow. The plunder of the monasteries furnished him with reasons equally conclusive for turning heresy into law, and an obsequious Parliament and Convocation were always at hand to give the sanction of the law to the ever versatile tenets of the king. Sensuality and rapacity were, therefore, the most effective reformers of the errors of the Church of Rome in England. After his death, and that of his short-lived son, Mary, the daughter of Catherine of Arragon, restored the papal authority in all its despotism and all its cruelty; and Elizabeth, the daughter of Anne Boleyn, restored again the Protestant supremacy upon the ruin of the triple tiara. The history of the Reformation in England is, therefore, the history of the lascivious and brutal passions of Henry the Eighth; of the cruel and unmerited sufferings of his wives, and of the conflicting interests, bitter prejudices, and violent tempers of his two daughters. The principles of Elizabeth were not less arbitrary than those of her father; and her successors of the house of Stuart, James, and Charles the First, continued to countenance the Reformation just so far as its establishment contributed to the support and extension of their own temporal power; and to resist, with the most inveterate and bigoted spirit of persecution, every step of further advancement to restore to its pristine purity and simplicity the religion of the meek and lowly Jesus.

Edition: current; Page: [18]

But even this half-way reformation, adulterated as it was by its connection with the government of the state, and with the passions of individuals, still leaned for its support from human reason upon the learning and intellect of the schools. When Henry the Eighth had exhausted all the resources of his temporal power, and of his personal influence, in the vain attempt to prevail upon the Pope to dissolve his marriage with Catherine, his last resort for authority to dissolve it was to the opinions of the universities.

The universities, in so far as their decisions were invited, were but too well versed in the ways of the world. To the eye of reason, of justice, and of humanity, nothing could be more unjustifiable than the dissolution of the marriage of Henry the Eighth and of Catherine of Arragon. There was no consanguinity between them. They were, indeed, within the Levitical degrees of prohibition; but this was a mere positive ordinance, to which, in that same law, the case of Henry and of Catherine formed an exception, under which their marriage was not only not forbidden, but commanded. They had been married twenty years; had several children, of whom Mary was living; and, base and brutal as the conduct of Henry was, he bore ample testimony, until and after her death, to the purity and tenderness and conjugal fidelity of Catherine. They had been married by a dispensation from the Pope, who often did, and has continued until this day to grant, without question from Roman Catholics, similar dispensations for marriages, even of persons in the blood relation of uncle and niece. The dissolution of such a marriage is, therefore, revolting to every honest and every generous sentiment; yet almost all the universities decided that the marriage was unlawful, and that the offspring of it was of spurious birth. Impartial readers of history will look back to this panderism of learning to the profligacy of Henry the Eighth, when they pass judgment upon the Catholic bigotry of Mary, and upon her bloody persecution of the Protestants when she came to the throne. But the universities are not to be estimated altogether by their decisions. These are warped by temporal interests and sordid passions; but it is the studies to which they afford access that constitute their glory. The authorities of the university might be exercised and abused by the expulsion of Locke or by the application of the scourge to the person of Milton, yet Edition: current; Page: [19] there it was that Milton and Locke drew the nutriment which made them the pride and glory of their country.

The English universities were the cradles of the New England colonies; and the Reformation was their nursing-mother. For although the successive kings and queens of England, with their sycophant Parliaments and Synods, could shape and mould the reformation of the law, according to the standard of their politics and their vices, they could not so control the march of mind in the universities. From the moment when the spell of human authority was broken, the right of private judgment resumed its functions; and when the student had been told that the only standard of faith was in the Scriptures, to prescribe creeds upon him under pains and penalties, however reasonable it might appear at White Hall, in St. Stephen’s Chapel, or in Leadenhall Street, was but inconsistency, absurdity, and tyranny at Cambridge and even at Oxford.

The unavoidable consequence of the exercise of private judgment is the diversity of faith. Human nature is so constituted, that in every thing relating to religion, different minds reasoning upon the same facts come to different conclusions. This diversity furnishes to the Church of Rome one of her most powerful arguments for the necessity of a common standard, to which all Christians may resort for the regulation of their faith; and the variations of the Protestant churches were the theme upon which the eloquent Bishop of Meaux expatiated with the greatest effect in his controversial writings for the conversion of heretics.

The investigating mind, however, cannot be arrested in its career. Henry the Eighth, Edward the Sixth, Mary, Elizabeth, and James could successively issue their edicts, commanding their subjects alternately to believe or disbelieve this or that tenet of the Romish Church, to invest the Pope with infallibility, or to strip him of that attribute, and they could apply the secular arm with equal efficacy to sustain truth or error. The right of private judgment for the regulation of faith was still the cornerstone of the Reformation, and however it might be suppressed in the corrupted currents of the world, it was enjoyed and had its full operation in the universities. Among the students, who resorted to them in search of education and science, there were numbers who gave the range of free inquiry to their minds, and Edition: current; Page: [20] who spurned the shackles of power. In the struggle between the government to arrest the progress of the Reformation, and individuals whose spirit could not be subdued, the fury of religious persecution could be satiated with nothing less than death as the punishment of non-conformity. Banishment, in other ages and for other crimes, considered as one of the severest of penalties, was an indulgence denied to the Puritans, and the first of the New England colonies was settled by fugitives from their country, who, at the peril of their lives, had escaped from the unrelenting tyranny of their native land.

The seminal principle of the New England colonies, therefore, was religious controversy; and, from this element of their constitution, different from the principle of all preceding colonies, ancient or modern, consequences followed such as the world had never before witnessed.

One of these consequences was that the founders of these colonies were men of finished education and profound learning. It was at the universities, and in the pursuit of learning, that they had imbibed the principles which they believed, by which they acted, and for which they suffered. Another consequence was, that the same founders of those colonies were men at once deeply conscientious and inflexibly firm. It was impossible that they should have adopted their principles without previous investigation, anxious and profound. The conclusions to which they came were sincere, and they believed them important beyond any thing that this world could give or take away. Every motive that could operate upon selfish passions or worldly interests pointed them to the opposite doctrines. The spirit of martyrdom alone dictated to them those which they espoused. The name of Puritans, given them by their oppressors in derision, was characteristic of their purposes and of their conduct. It was the object of their labors and of their aspirations to restore to its simplicity and purity the religion of Jesus; and they alone, of all the sectarian reformers, adapted their system of discipline and of church government to their professions. They were even in that age, and before their emigration, denominated Independents. Their form of church government was democratical. Any number of individuals residing in a neighborhood of each other, competent to meet together in social worship under the same roof, associated themselves by a mutual covenant, Edition: current; Page: [21] and formed a church. They elected, by a majority of votes, their pastors, teachers, ruling elders, and deacons. Each church was independent of all others; and they ordained their ministers by imposition of hands of the brethren themselves. They abolished all superstitious observances, all unscriptural fasts and festivals, all symbolical idolatries; but, with a solemn and rigorous devotion of the first day of the week to the worship of God, they appropriated a small part of one weekly day to a lecture preparatory for the Sabbath, one annual day, at the approach of spring, to humiliation before their Maker, and to prayer for his blessing upon the labors of the husbandman; and one day, towards the close of the year, in grateful thanksgiving to Heaven for the blessing of the harvest and the abundance of the fields.

Among the first fruits of this love and veneration for learning was the institution of Harvard College, within the first ten years after the arrival of Governor Winthrop. And with this was soon afterwards connected another institution, not less remarkable nor less operative upon the subsequent history and character of New England. In the year 1647, an ordinance of the General Court provided as follows: “To the end that learning may not be buried in the graves of our forefathers, in church and commonwealth, the Lord assisting our endeavors: It is therefore ordered by this court, and authority thereof, that every township within this jurisdiction, after the Lord hath increased them to the number of fifty householders, shall then forthwith appoint one within their towns to teach all such children as shall resort to him, to write and read, whose wages shall be paid, either by the parents or masters of such children or by the inhabitants in general, by way of supply, as the major part of those that order the prudentials of the town shall appoint; provided that those who send their children be not oppressed by paying much more than they can have them taught for in other towns.”

“And it is further ordered that where any town shall increase to the number of one hundred families or householders, they shall set up a grammar-school, the master thereof being able to instruct youth so far as they may be fitted for the university; and if any town neglect the performance hereof above one year, then every such town shall pay five pounds per annum to the next such school till they shall perform this order.”

Edition: current; Page: [22]

This institution, requiring every town consisting of one hundred families or more, to maintain a grammar-school at which youths might be fitted for the university, was not only a direct provision for the instruction, but indirectly furnished a fund for the support of young men in penurious circumstances, immediately after having completed their collegiate career, and who became the teachers of these schools.

And thus it was that John Adams, shortly after receiving his degree of Bachelor of Arts at Harvard College, in the summer of 1755, became the teacher of the grammar-school in the town of Worcester.

He had not then completed the twentieth year of his age. Until then his paternal mansion, the house of a laboring farmer in a village of New England, and the walls of Harvard College, had formed the boundaries of his intercourse with the world. He was now introduced upon a more extensive, though still a very contracted theatre. A school of children is an epitome of the affairs and of many of the passions which agitate the bosoms of men. His situation brought him acquainted with the principal inhabitants of the place, nor could the peculiar qualities of his mind remain long altogether unnoticed among the individuals and families with whom he associated.

His condition, as the teacher of a school, was not and could not be a permanent establishment. Its emoluments gave but a bare and scanty subsistence. The engagement was but for a year. The compensation little above that of a common day-laborer. It was an expedient adopted merely to furnish a temporary supply to the most urgent wants of nature, to be purchased by the devotion of time, which would have otherwise been occupied in becoming qualified for the exercise of an active profession. To his active, vigorous, and inquisitive mind this situation was extremely irksome. But instead of suppressing, it did but stimulate its native energies. It is no slight indication of the extraordinary powers of his mind, that several original letters, written at that period of his life to his youthful acquaintance and friends, and of which he retained no copies, were preserved by the persons to whom they were written, transmitted as literary curiosities to their posterity, and, after the lapse of more than half a century, were restored to him, or appeared to his surprise in the public journals.

Edition: current; Page: [23]

Of these letters, one of the earliest in date was addressed to his friend and kinsman, Nathan Webb, written on the 12th of October, 1755, while he was yet under twenty. Fifty-two years afterwards it was returned to him by the son of Mr. Webb, long after the decease of his father, and was then first published in the Boston Monthly Anthology. The following is an exact copy of the original letter yet extant.

Worcester

,

12 October, 1755

.

All that part of creation which lies within our observation, is liable to change. Even mighty states and kingdoms are not exempted.

If we look into history, we shall find some nations rising from contemptible beginnings, and spreading their influence till the whole globe is subjected to their sway. When they have reached the summit of grandeur, some minute and unsuspected cause commonly effects their ruin, and the empire of the world is transferred to some other place. Immortal Rome was at first but an insignificant village, inhabited only by a few abandoned ruffians; but by degrees it rose to a stupendous height, and excelled, in arts and arms, all the nations that preceded it. But the demolition of Carthage, (what one should think would have established it in supreme dominion,) by removing all danger, suffered it to sink into a debauchery, and made it at length an easy prey to barbarians.

England, immediately upon this, began to increase (the particular and minute causes of which I am not historian enough to trace) in power and magnificence, and is now the greatest nation upon the globe. Soon after the Reformation, a few people came over into this new world for conscience sake. Perhaps this apparently trivial incident may transfer the great seat of empire into America. It looks likely to me: for if we can remove the turbulent Gallicks, our people, according to the exactest computations, will in another century become more numerous than England itself. Should this be the case, since we have, I may say, all the naval stores of the nation in our hands, it will be easy to obtain the mastery of the seas; and then the united force of all Europe will not be able to subdue us. The only way to keep us from setting up for ourselves is to disunite us. Divide et impera. Keep us in distinct colonies, Edition: current; Page: [24] and then, some great men in each colony desiring the monarchy of the whole, they will destroy each others’ influence and keep the country in equilibrio.

Be not surprised that I am turned politician. This whole town is immersed in politics. The interests of nations, and all the dira of war, make the subject of every conversation. I sit and hear, and after having been led through a maze of sage observations, I sometimes retire, and by laying things together, form some reflections pleasing to myself. The produce of one of these reveries you have read above. Different employments and different objects may have drawn your thoughts other ways. I shall think myself happy, if in your turn you communicate your lucubrations to me.

I wrote you sometime since, and have waited with impatience for an answer, but have been disappointed.

I hope that the lady at Barnstable has not made you forget your friend. Friendship, I take it, is one of the distinguishing glories of man; and the creature that is insensible of its charms, though he may wear the shape of man, is unworthy of the character. In this, perhaps, we bear a nearer resemblance to unembodied intelligences than in any thing else. From this I expect to receive the chief happiness of my future life; and am sorry that fortune has thrown me at such a distance from those of my friends who have the highest place in my affections. But thus it is, and I must submit. But I hope ere long to return, and live in that familiarity that has from earliest infancy subsisted between yourself and affectionate friend,

It is not surprising that this letter should have been preserved. Perhaps there never was written a letter more characteristic of the head and heart of its writer. Had the political part of it been written by the minister of state of a European monarchy, at the close of a long life spent in the government of nations, it would have been pronounced worthy of the united penetration and experience of a Burleigh, a Sully, or an Oxenstiern. Had the ministers who guided the destinies of Great Britain, had Chatham himself, been gifted with the intuitive foresight of distant futurity, which marks the composition of this letter, Chatham would have foreseen that his conquest of Canada in Edition: current; Page: [25] the fields of Germany was, after all, but a shallow policy, and that divided colonies and the turbulent Gallicks were the only effectual guardians of the British empire in America.

It was the letter of an original meditative mind; a mind as yet aided only by the acquisitions then attainable at Harvard College, but formed, by nature, for statesmanship of the highest order. And the letter describes, with the utmost simplicity, the process of operation in the mind which had thus turned politician. The whole town was immersed in politics. It was in October of the year 1755, that year “never to be forgotten in America,” the year memorable by the cruel expulsion of the neutral French from Nova Scotia, by Braddock’s defeat, and by the abortive expedition under Sir William Johnson against Crown Point. For the prosecution of the war, then just commenced between France and Britain, and of which the dominion of the North American continent was to be the prize, the General Court of Massachusetts Bay, but a short month before this letter was written, had held an unprecedented extraordinary session, convened by the lieutenant-governor of the province; and, sitting every day, including the Sabbath, from the 5th to the 9th of September, had made provision for raising within the province an additional force of two thousand men. Such was the zeal of the inhabitants for the annihilation of the French power in America! The interests of nations and the dira of war made the subject of every conversation. The ken of the stripling schoolmaster reached far beyond the visible horizon of that day. He listened in silence to the sage observations through which he was led by the common talk of the day, and then, in his solitary reflections, looked for the revelation of the future to the history of the past; and in one bold outline exhibited by anticipation a long succession of prophetic history, the fulfilment of which is barely yet in progress, responding exactly hitherto to his foresight, but the full accomplishment of which is reserved for the development of after ages. The extinction of the power of France in America, the union of the British North American colonies, the achievement of their independence, and the establishment of their ascendency in the community of civilized nations by the means of their naval power, are all Edition: current; Page: [26] foreshadowed in this letter, with a clearness of perception, and a distinctness of delineation, which time has hitherto done little more than to convert into historical fact; and the American patriot can scarcely implore from the bounty of providence for his country a brighter destiny than a realization of the remainder of this prediction, as exact as that upon which time has already set his seal.

But it is not in the light only of a profound speculative politician that this letter exhibits its youthful writer. It lays open a bosom glowing with the purest and most fervid affections of friendship. A true estimate of the enjoyments of friendship is an unerring index to a feeling heart; an accurate discernment of its duties is a certain test of an enlightened mind. In the last days of his eventful life, the greatest orator, statesman, and philosopher of Rome selected this as the theme of one of those admirable philosophical dissertations, by the composition of which he solaced his sorrows for the prostration of his country’s freedom, and taught to after ages lessons of virtue and happiness, which tyranny itself has never been able to extinguish. Yet that dissertation, sparkling as it is with all the brilliancy of the genius of Cicero, contains not an idea of the charms of friendship more affecting or sublime than the sentiment expressed in this letter, that friendship is that in which our nature approaches the nearest to that of the angels. Nor was this, in the heart of the writer, a barren or unfruitful plant. He was, throughout life, a disinterested, an affectionate, a faithful friend. Of this, the following narrative will exhibit more than one decisive proof.

It was his good fortune, even at that early period of life, to meet with more than one friend, of mind congenial with his own. Among them was Charles Cushing, who had been his classmate at Harvard, and Richard Cranch, a native of Kingsbridge in England, a man whose circumstances in life had made him the artificer of his own understanding as well as of his fortunes. Ten years older than John Adams, an adventurous spirit and the love of independence had brought him at the very threshold of life to the American shores, a friendless wanderer from his native land. Here, by the exercise of irreproachable industry, and by the ingenuity of a self-taught skill in mechanics, he had made for himself a useful and profitable Edition: current; Page: [27] profession. Even before the close of his career at college, John Adams had formed the acquaintance of this excellent man; and, notwithstanding the disparity of their age, they were no sooner known to each other than they were knit together in the bands of friendship, which were severed only by death.

Immediately after he had taken his bachelor’s degree, upon his contracting the engagement to keep the school at Worcester, he had promised his friend, Cranch, to write him an account of the situation of his mind. The following letter, preceding by about six weeks that to Mr. Webb, already given, and remarkable as the earliest production of his pen known to be extant, is the performance of that promise.

Worcester

,

2 September, 1755

.

Dear Sir,—

I promised to write you an account of the situation of my mind. The natural strength of my faculties is quite insufficient for the task. Attend, therefore, to the invocation. O thou goddess, muse, or whatever is thy name, who inspired immortal Milton’s pen with a confusion ten thousand times confounded, when describing Satan’s voyage through chaos, help me, in the same cragged strains, to sing things unattempted yet in prose or rhyme. When the nimble hours have tackled Apollo’s coursers, and the gay deity mounts the eastern sky, the gloomy pedagogue arises, frowning and lowering like a black cloud begrimed with uncommon wrath, to blast a devoted land. When the destined time arrives, he enters upon action, and, as a haughty monarch ascends his throne, the pedagogue mounts his awful great chair, and dispenses right and justice through his whole empire. His obsequious subjects execute the imperial mandates with cheerfulness, and think it their high happiness to be employed in the service of the emperor. Sometimes paper, sometimes his penknife, now birch, now arithmetic, now a ferule, then A B C, then scolding, then flattering, then thwacking, calls for the pedagogue’s attention. At length, his spirits all exhausted, down comes pedagogue from his throne, and walks out in awful solemnity, through a cringing multitude. Edition: current; Page: [28] In the afternoon, he passes through the same dreadful scenes, smokes his pipe, and goes to bed. Exit muse.

The situation of the town is quite pleasant, and the inhabitants, as far as I have had opportunity to know their character, are a sociable, generous, and hospitable people; but the school is indeed a school of affliction. A large number of little runtlings, just capable of lisping A B C, and troubling the master. But Dr. Savil tells me, for my comfort, “by cultivating and pruning these tender plants in the garden of Worcester, I shall make some of them plants of renown and cedars of Lebanon.” However this be, I am certain that keeping this school any length of time, would make a base weed and ignoble shrub of me.

Pray write me the first time you are at leisure. A letter from you, Sir, would balance the inquietude of school-keeping. Dr. Savil will packet it with his, and convey it to me.

When you see friend Quincy, conjure him, by all the muses, to write me a letter. Tell him that all the conversation I have had since I left Braintree, is dry disputes upon politics, and rural obscene wit. That, therefore, a letter written with that elegance of style and delicacy of humor which characterize all his performances, would come recommended with the additional charm of rarity, and contribute more than any thing (except one from you) towards making a happy being of me once more. To tell you a secret, I don’t know how to conclude neatly without invoking assistance; but as truth has a higher place in your esteem than any ingenious conceit, I shall please you, as well as myself most, by subscribing myself your affectionate friend,

The letter is a picture of the situation of the writer’s mind. And the first thing that occurs in it to observation, is the uneasiness of that situation. It is easy to perceive in it the fire of ambition, which had been kindled at the torch of science. The occupation of a schoolmaster could not satisfy his aspirations. Its authority excited in him sentiments, which could be described only in the strains of the mock heroic. His friend, Dr. Savil, for his encouragement, had held up to him the possible chances of future eminence which some of his pupils might obtain from his teaching; but the prospect was too contingent Edition: current; Page: [29] and too remote. The school was a school of affliction, and he dreaded the probable effect of a long continuance in it upon himself. To the situation of the town, and to the character and deportment of the inhabitants, he does ample justice; but neither the employment in which he was engaged nor the conversation of those with whom he associated could fill the capacities of his soul. To the ardent and meditative mind of a youth fresh from the college, there was doubtless something undefined to itself in the compass of its desires; but politics and obscenity, the ordinary range of conversation for vulgar minds, even in the highest condition of life, had no attractions for him. From the void left aching at the heart, after such social intercourse, he reverted to the charm of correspondence with friends like Cranch and Quincy—to elegance of style and delicacy of humor, for the restoration of his happiness.

At this time, however, he had not begun to deliberate upon the choice of a profession. The letter to Nathan Webb, so soon afterwards written, does, indeed, sufficiently foreshow that the cure of souls in a parish church was as little adapted to the faculties and propensities of the writer as the keeping of the town school at Worcester; but several months more passed away before he began to deliberate with himself upon his essential qualifications for the pastoral office.

On the 1st of April, 1756, in answer to a letter from his friend and classmate, Charles Cushing, who had advised him to pursue the clerical profession, he writes thus.

“My Friend,—I had the pleasure, a few days since, of receiving your favor of February 4th. I am obliged to you for your advice, and for the manly and rational reflections with which you enforced it. I think I have deliberately weighed the subject, and had almost determined as you advise. Upon the stage of life, we have each of us a part, a laborious and difficult part to act; but we are all capable of acting our parts, however difficult, to the best advantage. Upon common theatres, indeed, the applause of the audience is of more importance to the actors than their own approbation. But upon the stage of Edition: current; Page: [30] life, while conscience claps, let the world hiss. On the contrary, if conscience disapproves, the loudest applauses of the world are of little value. While our own minds commend, we may calmly despise all the frowns, all censure, all the malignity of man.

- “Should the whole frame of nature round us break,

- In ruin and confusion hurled;

- We, unconcerned, might hear the mighty crack,

- And stand unhurt amidst a falling world.”

We have, indeed, the liberty of choosing what character we shall sustain in this great and important drama. But to choose rightly, we should consider in what character we can do the most service to our fellow-men as well as to ourselves. The man who lives wholly to himself is of less worth than the cattle in his barn.”

The letter then proceeds to present a parallel between the three learned professions, as objects of selection for a young man at his entrance upon active life, and with reference to the principles thus laid down, that is, to the means afforded respectively by them, for support, independence, and for usefulness to others. From this survey of the professions, he draws the following somewhat dubious conclusion.

“Upon the whole, I think the divine (if he reveres his own understanding more than the decrees of councils or the sentiments of fathers; if he resolutely discharges the duties of his station according to the dictates of his mind; if he spends his time in the improvement of his head in knowledge and his heart in virtue, instead of sauntering about the streets;) will be able to do more good to his fellow-men, and make better provision for his own future happiness in this profession than in another. However, I am as yet very contented in the place of a schoolmaster. I shall not, therefore, very suddenly become a preacher.”

This conclusion shows that the state of his mind was yet unsettled upon the question then so deeply interesting to him. The parallel between the comparative eligibility of the professions was very imperfect. It wanted the basis of experience for facts upon which reason and judgment could operate. But the same question occurs from year to year to a multitude of youths issuing from the colleges of the country. The three Edition: current; Page: [31] professions may justly be considered as all equally necessary to the comfort and welfare of society. They are all equally honorable; nor can the palm of usefulness justly be awarded to either of them in preference to the other. All afford ample fields for the exercise of every talent and of every virtue that exalts or adorns the human character. To the ambition of taking part in public affairs, the law is the profession which affords the greatest facilities. But for the acquisition of eminence in it, the talent of extemporaneous public speaking is indispensable, and that talent is of rare endowment. It requires a conformation of physical organs and of intellectual powers of peculiar character, the foundation of which is the gift of nature, and without which the profoundest intellect and the most inventive imagination are alike unfitted for the conflicts of the bar, or of deliberative assemblies. In the choice of a profession, therefore, the youth advancing upon the threshold of life, while keeping his eye steadily fixed upon the fundamental principle laid down in this letter, and considering in what character he can do the most service to his fellow-men as well as to himself, should undergo a rigorous process of self-examination; should learn to estimate his own powers, and determine how far they will bear him out in the indulgence of his own inclinations.

For the profession of the law, John Adams had been pre-eminently gifted with the endowments of nature; a sound constitution of body, a clear and sonorous voice, a quick conception, a discriminating judgment, and a ready elocution. His natural temper was as quick as his conception. His confidence in his own judgment, founded on the consciousness of his powers, gave it a cast of stubbornness and inflexibility, perhaps necessary for the successful exercise of the duties of a lawyer, nor sometimes less necessary, though requiring more frequently the countercheck of self-control, in the halls of legislation and at the courts of kings. A deeply conscientious moral sense, combining with an open disposition, averse to all disguise or concealment, and with that quickness of temper, produced in after life an occasional irritability which he was not always able to suppress. A more imperturbable equanimity might have been better adapted to the controversies of his subsequent political life, to the cool and crafty profligacy of simulated friends Edition: current; Page: [32] and insidious rivals. But even the vehemence of virtuous indignation is sometimes useful in establishing the character and reputation of a young man rising to eminence at the bar without adventitious aid, and upon the solitary energy of his own faculties.

At the close of the above letter to Charles Cushing, there was the following short, but significant postscript:—

“P. S. There is a story about town that I am an Arminian.”

These few words afford the key to that change in his predilections and prospects which shortly afterwards brought him to the final determination of intrusting his future fortunes to the profession of the law. From the 18th of November, 1755, he had kept an occasional diary; in which, under the date of Sunday, the 22d of August, 1756, is the following entry.

“Yesterday I completed a contract with Mr. Putnam to study law under his inspection for two years. I ought to begin with a resolution to oblige and please him and his lady in a particular manner. I ought to endeavor to oblige and please everybody, but them in particular. Necessity drove me to this determination, but my inclination, I think, was to preach. However, that would not do. But I set out with firm resolutions, I think, never to commit any meanness or injustice in the practice of law. The study and practice of law, I am sure, does not dissolve the obligations of morality or of religion. And although the reason of my quitting divinity was my opinion concerning some disputed points, I hope I shall not give reason of offence to any in that profession by imprudent warmth.”

In letters to his friends, Cranch and Charles Cushing, of 29th August and of 18th and 19th October, 1756, he speaks more explicitly. To the first, within a week after having completed his contract with Mr. Putnam, he writes:—

I am set down with a design of writing to you. But the narrow sphere I move in, and the lonely, unsociable life I lead, can furnish a letter with little more than complaints of my hard fortune. I am condemned to keep school two years longer. This I sometimes consider as a very grievous calamity, and almost sink under the weight of woe. But shall Edition: current; Page: [33] I dare to complain and to murmur against Providence for this little punishment, when my very existence, all the pleasure I enjoy now, and all the advantages I have of preparing for hereafter, are expressions of benevolence that I never did and never could deserve? Shall I censure the conduct of that Being who has poured around me a great profusion of those good things that I really want, because He has kept from me other things that might be improper and fatal to me if I had them? That Being has furnished my body with several senses, and the world around it with objects suitable to gratify them. He has made me an erect figure, and has placed in the most advantageous part of my body the sense of sight. And He has hung up in the heavens over my head, and spread out in the fields of nature around me, those glorious shows and appearances with which my eyes and my imagination are extremely delighted. I am pleased with the beautiful appearance of the flower, and still more pleased with the prospect of forests and of meadows, of verdant fields and mountains covered with flocks; but I am thrown into a kind of transport when I behold the amazing concave of heaven, sprinkled and glittering with stars. That Being has bestowed upon some of the vegetable species a fragrance that can almost as agreeably entertain our sense of smell. He has so wonderfully constituted the air we live in, that, by giving it a particular kind of vibration, it produces in us as intense sensations of pleasure as the organs of our bodies can bear, in all the varieties of harmony and concord. But all the provision that He has made for the gratification of my senses, though very engaging instances of kindness, are much inferior to the provision for the gratification of my nobler powers of intelligence and reason. He has given me reason, to find out the truth and the real design of my existence here, and has made all endeavors to promote that design agreeable to my mind, and attended with a conscious pleasure and complacency. On the contrary, He has made a different course of life, a course of impiety and injustice, of malevolence and intemperance, appear shocking and deformed to my first reflection. He has made my mind capable of receiving an infinite variety of ideas, from those numerous material objects with which we are environed; and of retaining, compounding, and arranging the vigorous impressions which we receive from these into all the Edition: current; Page: [34] varieties of picture and of figure. By inquiring into the situation, produce, manufactures, &c., of our own, and by travelling into or reading about other countries, I can gain distinct ideas of almost every thing upon this earth at present; and by looking into history, I can settle in my mind a clear and a comprehensive view of the earth at its creation, of its various changes and revolutions, of its progressive improvement, sudden depopulation by a deluge, and its gradual repeopling; of the growth of several kingdoms and empires, of their wealth and commerce, their wars and politics; of the characters of their principal leading men; of their grandeur and power; their virtues and vices; of their insensible decays at first, and of their swift destruction at last. In fine, we can attend the earth from its nativity, through all the various turns of fortune; through all its successive changes; through all the events that happen on its surface, and all the successive generations of mankind, to the final conflagration, when the whole earth, with its appendages, shall be consumed by the furious element of fire. And after our minds are furnished with this ample store of ideas, far from feeling burdened or overloaded, our thoughts are more free and active and clear than before, and we are capable of spreading our acquaintance with things much further. Far from being satiated with knowledge, our curiosity is only improved and increased; our thoughts rove beyond the visible diurnal sphere, range through the immeasurable regions of the universe, and lose themselves among a labyrinth of worlds. And not contented with knowing what is, they run forward into futurity, and search for new employment there. There they can never stop. The wide, the boundless prospect lies before them! Here alone they find objects adequate to their desires. Shall I now presume to complain of my hard fate, when such ample provision has been made to gratify all my senses, and all the faculties of my soul? God forbid. I am happy, and I will remain so, while health is indulged to me, in spite of all the other adverse circumstances that fortune can place me in.

I expect to be joked upon, for writing in this serious manner, when it shall be known what a resolution I have lately taken. I have engaged with Mr. Putnam to study law with him two years, and to keep the school at the same time. It will be hard work; but the more difficult and dangerous the enterprise, a Edition: current; Page: [35] brighter crown of laurel is bestowed on the conqueror. However, I am not without apprehensions concerning the success of this resolution, but I am under much fewer apprehensions than I was when I thought of preaching. The frightful engines of ecclesiastical councils, of diabolical malice and Calvinistical good-nature never failed to terrify me exceedingly whenever I thought of preaching. But the point is now determined, and I shall have liberty to think for myself without molesting others or being molested myself. Write to me the first good opportunity, and tell me freely whether you approve my conduct.

Please to present my tenderest regards to our two friends at Boston, and suffer me to subscribe myself your sincere friend,

Some of the thoughts in the first part of this letter had, apparently, been suggested by the papers of Addison in the “Spectator” upon the pleasures of the imagination. The additions discover a mind grasping at universal knowledge, and considering the pursuit of science as constituting the elements of human happiness. These letters are given entire; for although no copy of them was retained by their writer, yet nothing written by him in after life bears more strongly the impress of his intellectual powers, and none set forth with equal clearness the principles to which he adhered to his last hour. He will hereafter be seen in the characters of a lawyer, patriot, statesman, founder of a mighty empire, upon the great and dazzling theatre of human affairs. In these letters, and in the journals of that period in which they were written, we behold him, a solitary youth, struggling with the “res angusta domi,” against which it has, in all ages, proved so difficult to emerge; his means of present subsistence depending solely upon his acquisitions at college and upon his temporary contract for keeping school; his prospects of futurity, dark and uncertain; his choice of a profession different from that which his father had intended, and from that to which he had been led by his own inclinations and by the advice of his friends.

This profession, besides, then labored under the disadvantage of inveterate prejudices operating against it in the minds of the people of his native country. Among the original settlers of New England there were no lawyers. There could, indeed, Edition: current; Page: [36] be no field for the exercise of that profession at the first settlement of the colonies. The general court itself was the highest court of judicature in the colony, for which reason no practising lawyer was permitted to hold a seat in it. Under the charter of William and Mary, the judicial was first separated from the legislative power, and a superior court of judicature was established in 1692, from whose decisions in all cases exceeding three hundred pounds sterling there was an appeal to the king in council. Under this system, it was not possible that the practice of the bar should either form or lead to great eminence. Hutchinson says he does not recollect that the town of Boston ever chose a lawyer to represent it under the second charter, until the year 1738, when Mr. John Read was chosen, but was left out the next year; and in 1758 and ’59 Mr. Benjamin Pratt was member for the town. From that time, he observes, that lawyers had taken the lead in all the colonies, as well as afterwards in the continental congress.

The controversies which terminated in the war and revolution of independence were all upon points of law. Of such controversies lawyers must necessarily be the principal champions; but at the time when John Adams resolved to assume the profession of the law, no such questions existed; and the spirit of prophecy itself could scarcely have foreseen them. A general impression that the law afforded a wider range for the exercise of the faculties of which he could not be unconscious, than the ministry, and still more, a dread and horror of Calvinistical persecution, finally fixed his determination.

But in taking a step of so much importance and hazard, he was extremely anxious to obtain the approbation of his friends. On the 19th of October, 1756, he wrote thus to Charles Cushing.

Worcester

,

19 October, 1756

.

My Friend,—

I look upon myself obliged to give you the reasons that induced me to resolve upon the study and profession of the law, because you were so kind as to advise me to a different profession. When yours came to hand, I had thoughts of preaching, but the longer I lived and the more experience I had of that order of men, and of the real design of that institution, Edition: current; Page: [37] the more objections I found in my own mind to that course of life. I have the pleasure to be acquainted with a young gentleman of a fine genius, cultivated with indefatigable study, of a generous and noble disposition, and of the strictest virtue; a gentleman who deserves the countenance of the greatest men, and the charge of the best parish in the province. But with all these accomplishments, he is despised by some, ridiculed by others, and detested by more, only because he is suspected of Arminianism. And I have the pain to know more than one, who has a sleepy, stupid soul, who has spent more of his waking hours in darning his stockings, smoking his pipe, or playing with his fingers, than in reading, conversation, or reflection, cried up as promising young men, pious and orthodox youths, and admirable preachers. As far as I can observe, people are not disposed to inquire for piety, integrity, good sense, or learning, in a young preacher, but for stupidity (for so I must call the pretended sanctity of some absolute dunces), irresistible grace, and original sin. I have not, in one expression, exceeded the limits of truth, though you think I am warm. Could you advise me, then, who you know have not the highest opinion of what is called orthodoxy, to engage in a profession like this?

But I have other reasons too numerous to explain fully. This you will think is enough. . . .

The students in the law are very numerous, and some of them youths of which no country, no age, would need to be ashamed. And if I can gain the honor of treading in the rear, and silently admiring the noble air and gallant achievements of the foremost rank, I shall think myself worthy of a louder triumph than if I had headed the whole army of orthodox preachers.

The difficulties and discouragements I am under are a full match for all the resolution I am master of. But I comfort myself with this consideration—the more danger the greater glory. The general, who at the head of a small army encounters a more numerous and formidable enemy, is applauded, if he strove for the victory and made a skilful retreat, although his army is routed and a considerable extent of territory lost. But if he gains a small advantage over the enemy, he saves the interest of his country, and returns amidst the acclamations of Edition: current; Page: [38] the people, bearing the triumphal laurel to the capitol. (I am in a very bellicose temper of mind to-night; all my figures are taken from war.)

I have cast myself wholly upon fortune. What her ladyship will be pleased to do with me, I can’t say. But wherever she shall lead me, or whatever she shall do with me, she cannot abate the sincerity with which I trust I shall always be your friend,

The day before the date of this letter, he had written to Mr. Cranch one of similar import, repeating the request for his opinion upon the determination he had taken. It is remarkable that his purpose was not approved by either of the friends whom he consulted. They thought his undertaking inconsiderate and rash; and Mr. Cranch, in a subsequent answer to his inquiries, advised him to reconsider his resolution, and devote his life to the profession of a divine.

But his lot was cast, and he persevered. For the two succeeding years, six hours of every day were absorbed in his laborious occupation of a schoolmaster, while the leisure left him in the remnants of his time was employed in the study of the law.

In the interval between the dates of his two letters to Charles Cushing, on the choice of a profession, some extracts from his Edition: current; Page: [39] diary may indicate the progress of his mind towards the conclusion at which it arrived. Soon after he left college, he adopted the practice of entering in a commonplace book extracts from his readings. This volume commences with the well known verses of Pythagoras:—

- Μηδ’ ὕπνον μαλακοῖσιν ἐπ’ ὄμμασι προσδέξασϑαι,

- Ποὶν τῶν ἡμερινῶν ἔργων τρὶς ἕκαστον ἔπελϑεῖν·

- Πῆ παρέβην, Τί δ’ ἔρεξα; Τί μοι δέον οὐκ ἐτελέσϑη;

These verses appear to have suggested to him the idea of keeping a diary; the method best adapted to insure to the Pythagorean precept practical and useful effect. It was kept irregularly, at broken intervals, and was continued through the whole active period of his life. Not, however, as a daily journal, nor as a record of the incidents of his own life. It was kept on separate and loose sheets of paper, of various forms and sizes, and between which there was no intentional chain of connection. In this diary, together with notices of the trivial incidents of his daily life, the state of the weather, the attendance upon his school, the houses at which he visited, and the individuals with whom he associated, are contained his occasional observations upon men and things, and the reflections of his mind, occasioned whether by the conversations which occurred in his intercourse with society, or by the books which he read. The predominating sentiment in his mind was the consciousness of his own situation, and the contemplation of his future prospects in life.

- “The world was all before him, where to choose

- His place,”

and the considerations upon which he was bound to fix his choice were long and often revolved before they ripened into their final determination.