“If Chinese scholars would bring the ancient literature near to us, if they would show us something in it that really concerns us, something that is not merely old but eternally young, Chinese studies would soon take their place in public estimation by the side of Indo-European, Babylonian, and Egyptian scholarship. There is no reason why China should remain so strange, so far removed from our common interests.”—Prof. Max Muller, in Nineteenth Century for May, 1891.

I dedicate THIS BOOK to MY WIFE.

INTRODUCTION TO THE SHI KING.*

Whatever be the merits of this collection of the venerated ancient poetry of the Chinese, it possesses one quality which ought to have weight with the European reader: it represents, as in a mirror, the circumstances, the thoughts, the habits, the joys and sorrows of persons of all classes of society in China 3,000 years ago, pourtrayed by themselves. In it we have some of the oldest writings of that ancient race of strange custom and peculiar ideas. And yet, as proving that human nature is the same in its feelings and humours, and in its virtues and vices, despite the limits of millenniums and the boundaries of continents, there are pages in which we feel ourselves standing in the midst of the modern life of Europe. We are introduced to a people and a country till of late little known, but which we find here to have been possessed of a moderately high civilization and a literature at a time when our own forefathers were actual barbarians roaming their virgin forests.

It is a common remark that China, though thus early civilized, has stood still during the thirty or forty Edition: current; Page: [8] centuries over which its history takes us; but this is not exactly true. Probably at the date of these Odes the country might best be compared to our own in the feudal times, for China had then a feudal system. There are many things in the book which are antiquated and out of date and fashion to the Chinese themselves; but the language, and mode of thought, and many usages are substantially the same as those we see to-day.

The typical Chinaman has ever been far more a man of feeling than he is commonly reputed to be. With him, from the earliest times, music and poetry have always been held in higher estimation than the plastic arts; and he will usually be found to prefer the poetic exposition of a subject to its treatment in matter-of-fact prose. Metrical composition continues to be regarded by him as an essential requirement for one who claims to be an educated man. And whatever moves his soul turns in his language into rhyme with the greatest ease. Chinese is a language more abounding in rhymes than any other, probably, in the world. This is owing to the paucity of sounds, the changes being rung on a few hundred monosyllables, vocalizing with variation of tone many thousands of characters. Herein, also, the history of Chinese poetry differs from that of Western nations. Chinese verse began with rhyme, and it seems (see the Festal Odes of Shang, the oldest in the book) that the older the poetry is, the greater is the frequency of rhymes; whereas, in Western poetry, as is well known,—whether Greek, Latin, or English,—measure and not rhyme was its characteristic in the earliest stage.

Down to the first half of the eighth century bc, there had existed in China the practice of collecting the Edition: current; Page: [9] popular ballads in each of the feudal States. Snatches of verse, many of which were at first mere “poems of occasion,” as Goethe would have called them, became at length, if touching a popular chord, national ballads. These collections were, from time to time, communicated to the Government upon its requisition, the avowed object of the ruler being to keep his finger upon the pulse of the nation; for it was recognized even then that national ballads are a power in a country, and show, moreover, how a State is being governed. It is to this practice that we owe the preservation of half of the number of pieces in the Shi King—viz., the Fung, or Volkslieder, which compose the First Part. Other poems belong to the upper and highest classes of society, such as political songs, often abounding with bitter criticism of the condition of the country, Odes of lamentation by worried and wearied or slandered officials, festal Odes commonly sung on fixed occasions at the court of the sovereign or of the feudal princes, and sacred hymns sung at the sacrifices to the spirits of the royal ancestry.

We are informed by Sze-ma Ts‘ien, one of the greatest of China’s old historians, that these ancient poems numbered more than three thousand, and that Confucius made selections from them of such as would be likely to be serviceable for the promoting of propriety and righteousness. This was done about the year 483 bc The collection, as it left the sage’s hand consisted of 311 pieces, of which six have been lost (as indicated in Part II.). Of the remaining 305 all but the last five relate to the dynasty of Chow, and range in date from the twelfth to the seventh century bc They are thus often called the Chow poems. The last five, Edition: current; Page: [10] though placed last, belong to a remoter date, viz., to the time of the preceding dynasty of Shang* (bc 1766-1122).

Thus the Shi King claims an antiquity as high as, or even higher than, that of the Hebrew Psalms, and somewhat like that of the Hindu Rig-Veda. Yet it cannot be compared with either, having very little in common with either. There is in it vastly less of religious feeling and sentiment than in the Psalms, and it is wanting almost wholly in the mythology of the Rig-Veda. It is not indeed, in one sense of the word, a religious book. Most of it is eminently secular and human; and when Professor Legge prepared to include it in the Oxford Edition of “Sacred Books of the East,” edited by Professor Max Müller, he found that only a small portion could really be denominated sacred, and thereupon contributed that small portion, in prose.

Of many of the ballads Confucius might well have been asked why he retained them on his expurgation of the larger collection, and how they were to conduce at all to propriety and righteousness. His reply would have been, probably, that where the mention of impropriety or vice occurs it is only that it may be inwardly denounced and avoided, or that it was the result of bad government and example, and, as such, a warning. Or he might, as many of the native commentators have done, have interpreted many a simple love-song as having reference to political affairs, and as not being Edition: current; Page: [11] what it seemed. It is certain that he himself placed a great value upon the Odes. He loved to discourse upon them, as all his admirers have since done, perpetually quoted them in his teachings, and exhorted his disciples over and over again to study them, with a view to a right education, knowledge of self, and as an incitement to sociability. It is remarkable, however, that he often singles out for especial praise those passages which we should deem as of least worth. For example, of the first twenty-five in this book he does not hesitate to say, “He who has not studied them is like a man with his face turned to a wall.” Probably he so regarded these, not so much for their intrinsic merit as for their illustration of the reforms achieved among the people by the beneficent Wăn. Also of the last line but one of IV. iv. 1 (“On a Noble Horse-breeder”) he remarks, in the Analects, “The Odes are 300; one expression sums up all—‘mindfulness without deflection.’ ” It will be seen, by referring to the piece, and observing the corresponding lines in the other stanzas, how completely he disregarded the connection of these words.

It is in the longer pieces, particularly of Parts III. and IV., that we meet with something approaching to what we should call religious thought; and it is there that we find frequently recurring the name of God (Ti). the Supreme God (Shang Ti), and Heaven (T‘ien), regarded always as a personal Being, and as the Maker and Governor of men.*

Edition: current; Page: [12]So many treatises on the wide subject of the religion of the Chinese have been written, that it is unnecessary to repeat much of the information here. Suffice it to make the following remarks:—First, it must be borne in mind that we have in this book China presented to us previous to the teachings of Confucius himself, previous to the Taoist religion and philosophy, and long previous to the advent of Buddhism from India. We find belief in a Supreme God, invisible and incomprehensible, dwelling in the far-extending Heaven; Whose eye yet searches and scans clearly the world below:—

- “Say not, Heaven is so far, so high;

- Its Servants It is ever nigh;

- And daily are we here within Its sight;”*—

Who punishes and rewards men; Whose power it is vain for the wicked to withstand; Who is the source of all virtue and wisdom, and of all blessing. By Him kings rule, and dynasties rise and fall. In His special oversight are those lesser Rulers of men, who are on that account called “Sons of Heaven.” The knowledge of His will is learned from the order of nature; especially, however, through the conscience of the people. In one poem, indeed (III. i. 7), He is represented as “speaking” thrice, as if in person, to King Wăn; a statement which has sorely exercised the minds of the later native expositors. The spirits of good rulers like Wăn and his successors are represented as having at death Edition: current; Page: [13] gone into Heaven, and as being still actively concerned in the welfare of the kingdom below. They are now “Assessors” of God, and “meet to be linked with Heaven” in worship. They have great influence over the destiny of their descendants. From this we infer a general belief in the personal continued existence of the human soul after death, which belief prevails even now in the great mass of the Chinese people; although in this book there is no mention of retribution for evil in a future state, only temporal punishment, while the good are blessed and held in honoured remembrance on earth. From the same belief arose also the worship of ancestors by prayers, praises, and offerings at certain times; and of other Spirits,—spirits of heroes, of the “Father of Agriculture,” the “Father of War,” and others, originally, doubtless, men. But from some of the poems we learn that there was moreover a belief, on the part of high and low, in tutelary spirits,—spirits of earth, and air, and sky,—some presiding over mountains, streams, roads, and particular places and objects, some watching over the actions and secret life of men (III. iii. 2), and some in the heavenly bodies and constellations. It will be seen also that divination was practised, by the lines on scorched tortoise-shells, by straws or milfoil, or by handfuls of grain; and that there were augurs and interpreters of dreams attached to courts.

Mention is frequently made of temples. But these were in every case halls for ancestor-worship. There were no temples built for the worship of God, or for the propitiation of any spirits other than those of men; for men had been accustomed to dwell in houses. To God and to other spirits were erected altars open to the Edition: current; Page: [14] canopy of heaven. Although also the rites attending offerings and sacrifices were many and elaborate, the head of the family was the legitimate priest, as in the patriarchal times described in the book of Genesis: only rarely do we find a priest mentioned as acting on his behalf in certain parts of the ritual.

A strange and striking custom at royal sacrifices to ancestors was the employment of some of the younger members of the family as personators of the dead. These were clothed in the garments of the departed, were honoured as if for the while actually possessed by their spirits, ate and drank of the offerings, declared the pleasure of the departed in accepting them, and pronounced blessings on the offerer and his family.

Connected with these rites there was much festivity,—much eating and drinking and social pleasure, though all according to prescribed form and rule; and music and dancing enlivened the after proceedings. Many of the Odes describing them would show that religion with this ancient people was not regarded as incompatible with cheerfulness and conviviality, but as intimately to be connected therewith. It was then that the king was gladdened by being surrounded by his lords and princes, and by his own clansmen; and the bonds of union were strengthened.

To enter upon an exposition of the social life of the Chinese in these olden times, interesting as it would be, would be to begin a theme in which it would be difficult to know where to end. It is hoped that the Odes themselves will tell the reader almost all that is known, and that the notes and comments appended to each piece will sufficiently explain all peculiarities. The same remark Edition: current; Page: [15] applies to geographical matters, and also to the names of persons and unfamiliar things.

The China reigned over by the kings of the House of Chow was not in extent quite a fifth part of the present empire. Its northern limit was a little to the south of the modern capital Peking, and its southern scarcely reached the river Han. It may be described as an oblong tract of (say) 700 miles by 400, stretching from the Gulf of Pechili and the Yellow Sea westwards, and divided into two almost equal parts by the Hwang-bo, or Yellow River. It was surrounded by wild and often turbulent tribes.

A list is here given of the Kings of the Chow line down to the time of Confucius, together with the dates of their accession, and the number of the Odes that may with probability be assigned to each reign. For the last column I am indebted to the investigations of Dr. Legge. The Shang dynasty is placed first, as accounting for the five Odes belonging to it.

THE SHANG DYNASTY.

| Kings. | Date of Accession. | No. of Odes. |

| T‘ang, or Ch‘ing T‘ang to Chow Sin, or Shau (28 kings in all). | bc 1766 | } 5 |

| bc 1154 | } 5 |

TRANSITION PERIOD.

| “King” Wăn’s time, | bc 1184-1134 | about 35 |

THE CHOW DYNASTY.

| Kings. | Date of Accession. | No. of Odes. |

| Wu | bc 1122 | 8 or 9 |

| Ch‘ing | bc 1115 | 60 |

| K‘ang | bc 1078 | |

| Chau | bc 1052 | |

| Muh | bc 1001 | |

| Kung | bc 946 | |

I ( ) ) |

bc 934 | 5 |

| Hiau | bc 909 | |

I ( ) ) |

bc 894 | } 16 |

| Li | bc 878 | } 16 |

| Swăn | bc 827 | 25 |

| Yiu | bc 781 | 42 |

| P‘ing | bc 770 | } 67 |

| Hwan | bc 719 | } 67 |

| Chwang | bc 696 | 15 |

| Hi | bc 681 | 5 |

| Hwei | bc 676 | 12 |

| Siang | bc 651 | 13 |

| K‘ing | bc 618 | |

| K‘wang | bc 612 | |

| Ting | bc 606 | 2 |

| Kien | bc 585 | |

| Ling | bc 571 | |

| (Confucius born in 21st year of this reign). |

A short account should be given here of the rise of the Chow dynasty, which will throw light on a great part of the Shi King.

Chow Sin, the last of the Shang kings, although a man of powerful mind and great shrewdness, was yet ferociously cruel, and utterly unprincipled and licentious. The story of his reign, related in the Book of History, Edition: current; Page: [17] and in the comments on it, is almost too horrible to repeat. One of the princes, Ch‘ang, called the “Chief of the West” (afterwards known and honoured by the title of King Wăn), hearing of some of this tyrant’s enormities, spoke of them with regret to one of the ministers, who reported the conversation to the king, whereupon Wăn (for so let us now call him) was thrown into prison for a year. After his release, however, the king, at his request, abolished the cruel punishments which he had instituted, and appointed Wăn to be his Minister of War.

In the thirty-second year of his reign the king was admonished by one of his ministers for his bad government, but he paid no heed, and the minister left him; a second expostulated with him, and was imprisoned; a third admonished him still more sharply, whereon the king, angry at the interference, remarked, “I have heard that the heart of a sage has seven cavities; you consider yourself a sage.” He then ordered the minister’s execution, and that his heart should be torn out for his inspection.

Upon this and similar horrible proceedings one of the feudal princes, Wu, the son and successor of Wăn, who by dint of just and prudent administration had raised his principality to a state of great power and prosperity, was incited to call a conference of the princes of the various States. It was agreed to punish the king, and the agreement was confirmed by a solemn oath to Heaven. Wu marched against him at the head of an armed force on the plains of Muh (see III. i. 2); and though the king had raised an army of 70,000 men to resist him, they proved traitorous to him, and after some fighting opened the way for Wu’s forces. The king, Edition: current; Page: [18] finding himself betrayed, fled to his palace, arrayed himself in his best robes and jewels, set fire to the building, and so perished. His son Wu-Kang was taken prisoner, but gently treated by the conqueror, and afterwards associated with two of his brothers in the government of part of the kingdom. Wu’s entrance into the capital was glorious, and his noble yet friendly appearance captivated the people. He sent away all the women of the palace to their homes, but put to death the king’s paramour Han Ki, who had urged him on in his iniquities. After some time, not of his own seeking, but by the unanimous desire of the feudal princes and people he was made king, and became the founder of the dynasty of Chow, which lasted 874 years, viz., from bc 1122 to 248, during which period thirty-five kings and emperors reigned,—a period unequalled for length, and perhaps for importance, in the history of the many dynasties of China.

The new royal family was a very noble one, and traced itself back to a remote antiquity (see III. i. 3; III. ii. 1; and III. ii. 6). And to this day Wăn, and his two sons Wu and the famous Chow-Kung or Duke of Chow, are regarded as “sages,” and as men of renown both in letters and arms. The last named was regent for four years in place of his young nephew Ch‘ing, and was the author of the Book of Rites, or rules of etiquette, which are observed throughout the empire at this day. He is the reputed author also of several of these poems.

A word must be added on the structure of the poetry. It has already been noticed that these old Odes and ballads abound in rhymes. Very frequently three occur in a stanza of four lines, viz., in the first, second and Edition: current; Page: [19] last; sometimes we have quatrains proper, the first and third lines rhyming together, and the second and fourth. But in stanzas of more than four lines the rhymings are not at all regular. Towards the end of the book we find several pieces in blank verse, of lines also of varying length; while in the Odes of Shang there are two poems in which long stanzas contain a rhyme in every line.

A line consists regularly of four characters or monosyllabic words, often strong words, and pregnant with meaning in their collocation, defying an equally terse translation. One such rendering has been made by me (see I. iii. 2), which affords an excellent example of the enigmatical style of the original. There are exceptions where five, six, and even seven or more characters occur together; and, on the other hand, occasionally two or three are found constituting a line. A great peculiarity is that almost every line is a sentence in itself, which is a source of great comfort amid all the difficulties that beset the translator at every turn.

The number of lines in a stanza varies much. As, however, with very rare exceptions, every ballad and Ode in the book is here rendered in English line for line (much to the detriment of the English, perhaps, but as being a faithful reproduction of the Chinese), the structure in that respect is preserved, and no further notice is necessary. I was struck, on the receipt of a copy of the masterly translation into German by Victor von Strauss, on observing that he had followed the same course as myself, and that he has most admirably succeeded.

A remarkable peculiarity of the ballad style is this, that while in an English ballad we often find a refrain or Edition: current; Page: [20] chorus at the end of the verse, in Chinese there is something corresponding to that in the beginning,—some allusion to natural objects, bearing figuratively upon the subject, and repeated perhaps with variations in most of the succeeding verses. In a few instances we have indeed the proper chorus or refrain, e.g., in I. i. 9; I. vii. 2; I. vii. 21, &c. In many of these ballads also it will be observed that the whole subject is expressed in the first verse, and that all that follows is merely a playing with the same words or a slight variation from them, with a transposition of them for the sake of rhyme (see a good example in I. ii. 7). It should however be remembered that these pieces were intended to be sung; and what the poet had to say he wished to repeat in a round of words, which to him was no more monotonous a thing than the repetition of the music that accompanied it!

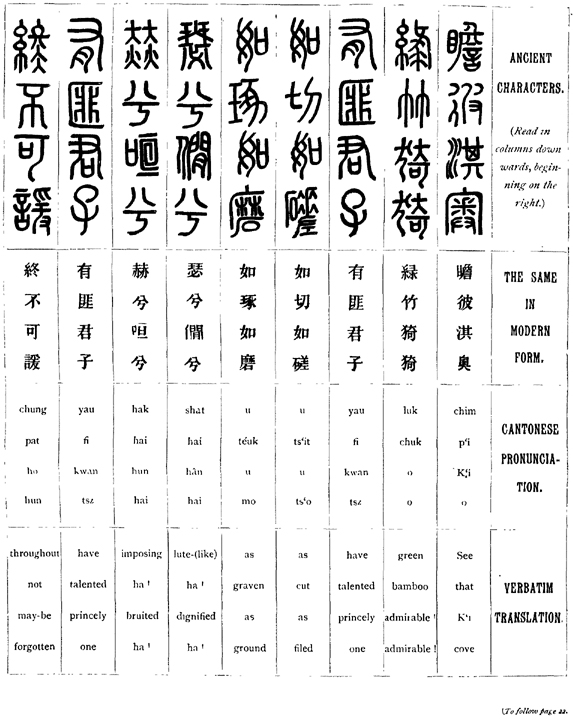

A specimen is subjoined of a stanza in the ancient and modern characters, with the Cantonese pronunciation without tones (the Cantonese dialect being said to be nearest to the ancient pronunciation), and the English equivalents.

The following version I have ventured—from the expressed opinion of some eminent sinologists in Hong Kong—to call a close translation. It is based upon a thorough study of the original text, aided by various standard Chinese commentaries; and for my further guidance I have availed myself much of the great work of Dr. Legge (Legge’s Chinese Classics, Vol. IV.). His critical notes to that prose translation have been invaluable. I could not well have undertaken the present work without the equipment which he provides in his prolegomena and notes. His work will doubtless remain Edition: current; Page: [21] always the standard one for students; and the erudition, the evidence of wide reading, and the patience and care displayed in it, make one indeed stand aghast. It seems to be the general opinion, however, that in the metrical version which followed, in which he availed himself of coadjutors (not sinologists) in England and elsewhere, he has been far from equalling himself. In that version has been adopted the plan of making many difficult preces intelligible by introducing into them (contrary to his expressed aim) phrases, and often several whole lines of explanatory matter which properly should be relegated to footnotes. It is amusing to find a reviewer of this poetic version inferring from it in one place (I. xiii. 1) a “philosophy of clothes.” “No Ritualist,” says this reviewer, “could attach more importance to the strings of a tippet or the lining of a robe than do the poets of the Shi”; in support of which he quotes from p. 173,

- “When thus you slight the laws of dress

- You’ll heed no laws at all!”

Unfortunately these lines are not to be found in the original “at all.”

Decidedly the best European metrical translation of the Shi King has been made by Victor von Strauss, already referred to; and my hope and ambition in publishing the present version is to have done as far as I can in the way of accuracy (though it may often have led to a little awkwardness of style) for English readers what he has done for German.

If it will detract in any degree from the apathy shown by English people towards the literature of the Far East, let me say in conclusion that though the “Poetry Classic” of the ancient Chinese may be despised as poetry, and Edition: current; Page: [22] may be looked upon only as rhymed prose, yet it has at least the merit of its age, and in one important respect it surpasses such poetry as that of Burns, and Byron, and Heine, and many other popular balladists: it has the merit of a greater morality. “I may assure the reader,” remarks Professor von der Gabelentz, of Leipsic, in a discussion on these poems, “that in this whole collection of Odes, and indeed in the whole canonic and classical literature of the Chinese, so far as I know it, there is not a line to be found which might not be read aloud without any hesitation in the most prudish society. I know no other literature, of the East or West, on which similar praise could be bestowed.”

PRONUNCIATION OF PROPER NAMES, &c.

- J, as in French.

- Ng commencing a word, like the same letters terminating one.

- a, as in father.

- ai, or ei, as in aisle, or eider.

- au, as in German, or like ow in cow.*

- é, as in fête.

- i (not followed by a consonant), as ee in see.

- u (followed by a consonant), as in bull.

- iu, as ew in new.

- úi, or úy, as ooi in cooing.

- ‘in the middle of a word denotes an aspirato (h).

SPECIMEN OF A STANZA IN THE ORIGINAL.

(See p. 81.)

CONTENTS.

- PART I. CHARACTERISTICS OF THE STATES.

- Book I.—The Odes of Chow and the South.

- 1. Song of Welcome to the Bride of King Wăn* . . . page 35

- 2. Industry and Filial Piety of Wăn’s Queen . . . 36

- 3. The Absent Husband . . . . . . . . 37

- 4. The Creepers . . . . . . . . . 38

- 5. The Locusts . . . . . . . . . 39

- 6. Bridal Song . . . . . . . . . 39

- 7. The Stalwart Rabbit-catcher . . . . . . 40

- 8. Song of the Plantain-gatherers . . . . . . 41

- 9. The Unapproachable Maidens . . . . . . 42

- 10. Wifely Solicitude . . . . . . . . . 42

- 11. The Lin . . . . . . . . . . 43

- Book II.—The Odes of Shâu and the South.

- 1. The Wedding-journey of a Princess . . . . . 44

- 2. A Reverent Helpmate . . . . . . . . 45

- 3. A Long-absent Husband . . . . . . . 45

- 4. The Young Wife’s zealous Care in the Worship of her Husband’s Ancestors . . . . . . . 46

- 5. The Memory of a Worthy Chieftain . . . . . 47

- 6. The Resisted Suitor . . . . . . . . 47

- 7. Dignity and Economy of King Wăn’s Councillors . . 48

- 8. The Lonely Wife . . . . . . . . . 49

- 9. Fears of Mature Maidenhood . . . . . . 50

- 10. Contented Concubines . . . . . . . . 50

- 11. Jealousy Overcome . . . . . . . . 51

- 12. The Cunning Hunter . . . . . . . . 51

- 13. The Royal Wedding . . . . . . . . 52

- 14. The Tsow Yu . . . . . . . . . 53 Edition: current; Page: [24]

- Book III.—The Odes of P‘ei.

- 1. Derelict . . . . . . . . . . 54

- 2. Supplanted . . . . . . . . . 56

- 3. Friends in Distress . . . . . . . . 57

- 4. Clouds Gathering . . . . . . . . . 58

- 5. The Storm . . . . . . . . . . 59

- 6. The Soldier sighs for Wife and Home . . . . . 59

- 7. The Discontented Mother . . . . . . . 60

- 8. Separation . . . . . . . . . . 61

- 9. Untimely Unions . . . . . . . . . 62

- 10. Lament of a Discarded Wife . . . . . . 62

- 11. A Prince and his Officers in Trouble . . . . . 64

- 12. Li finds no help in Wei . . . . . . . 65

- 13. Buffoonery at Court . . . . . . . . 65

- 14. Homesick . . . . . . . . . . 66

- 15. Official Hardships . . . . . . . . 67

- 16. Emigrants . . . . . . . . . . 68

- 17. Irregular Love-making . . . . . . . . 69

- 18. The New Tower . . . . . . . . . 70

- 19. The Two Sons . . . . . . . . . 70

- Book IV.—The Odes of Yung.

- 1. The Faithful Widow . . . . . . . . 72

- 2. Vile Doings at Court . . . . . . . . 73

- 3. Faint Praise . . . . . . . . . 74

- 4. Promiscuous Love-making . . . . . . . 75

- 5. Family Confusion . . . . . . . . 76

- 6. The Diligent Ruler . . . . . . . . 76

- 7. Reforms in Love and Marriage . . . . . . 77

- 8. Manners make the Man . . . . . . . 78

- 9. Honour to the Worthy . . . . . . . . 79

- 10. Thwarted . . . . . . . . . . 79

- Book V.—The Odes of Wei.

- 1. Praise of Duke Wu of Wei . . . . . . . 81

- 2. The Happy Recluse . . . . . . . . 82

- 3. An Epithalamium . . . . . . . . 83

- 4. Betrayed . . . . . . . . . . 84

- 5. Home Recollections . . . . . . . . 86

- 6. A Conceited Lordling . . . . . . . . 87

- 7. So Far, and yet so Near . . . . . . . 87 Edition: current; Page: [25]

- 8. The absent Hero-husband . . . . . . . 88

- 9. Wifeless and Forlorn . . . . . . . 88

- 10. Recompense . . . . . . . . . 89

- Book VI.—The Odes of the Royal Domain.

- 1. The Desolated Capitals: Lament of a Statesman . . 90

- 2. The Husband Abroad . . . . . . . 91

- 3. The Husband Returned . . . . . . . 92

- 4. Home-longings of the Frontier-guardsmen . . . 92

- 5. The Wife Divorced by Famine . . . . . . 93

- 6. A Wearied Statesman . . . . . . . 94

- 7. The Emigrant . . . . . . . . . 95

- 8. Absence makes the Heart grow fonder . . . . 96

- 9. Why she came not . . . . . . . . 96

- 10. The Loitering Lovers . . . . . . . 97

- Book VII.—The Odes of Ch‘ing.

- 1. Devotion of the People to Duke Wu of Ch‘ing . . . 98

- 2. Master Chung . . . . . . . . . 99

- 3. A Dashing, Popular Young Hunter . . . . . 100

- 4. The Same . . . . . . . . . . 100

- 5. Idle Manœuvring on the Borders . . . . . 102

- 6. Praise of a High Official . . . . . . . 102

- 7. Old Love should not be Ruptured . . . . . 103

- 8. The Good Housewife . . . . . . . 103

- 9. My Lady’s Charms . . . . . . . . 104

- 10. By-play . . . . . . . . . . 105

- 11. An Appeal . . . . . . . . . . 105

- 12. Tit for Tat . . . . . . . . . . 106

- 13. A Challenge . . . . . . . . . 106

- 14. Regrets . . . . . . . . . . 107

- 15. So Near, and yet so Far . . . . . . . 107

- 16. Joy at the Goodman’s Return . . . . . . 108

- 17. Neglected . . . . . . . . . . 108

- 18. Trust thy Last Friend against the World . . . . 109

- 19. One Modest Maid is more than All . . . . . 109

- 20. Fortuitous Concourse . . . . . . . 110

- 21. A Spring-tide Carnival . . . . . . . 110

- Book VIII.—The Odes of Ts‘i.

- 1. The Good Wife early wakes her Lord . . . . 112

- 2. The Conceited Sportsmen . . . . . . . 113 Edition: current; Page: [26]

- 3. The Coming of the Bridegroom . . . . . . 113

- 4. The Winsome Visitor . . . . . . . . 114

- 5. An Untimely Summons . . . . . . . 114

- 6. Criminal Relationships . . . . . . . 115

- 7. Seek not to be a Man before thy Time . . . . 116

- 8. The Hounds and the Huntsman . . . . . 117

- 9. Wăn-Kiang’s bold Escapades to Ts‘i . . . . . 117

- 10. Her shameless Meetings with Duke Siang . . . 118

- 11. Lamentful Praise of Duke Chwang of Lu . . . 118

- Book IX.—The Odes of Wei.

- 1. A Wealthy Niggard . . . . . . . . 120

- 2. Official Niggards . . . . . . . . 121

- 3. Secret Grief of a Statesman at the approaching Downfall of the State . . . . . . . . . 122

- 4. Reciprocated Affection . . . . . . . 123

- 5. Weary Officials contemplating a Retreat . . . . 124

- 6. The Thrifty Woodman and the Hoarding Official . . 124

- 7. Song of Farmers driven forth by Extortion . . . 126

- Book X.—The Odes of T‘ang.

- 1. Song of Peasantry at the Close of the Year . . . 127

- 2. Enjoy Life’s Good Things while you may . . . 128

- 3. Hwan-shuh and his Secret Band . . . . . 129

- 4. Admiration of some Chief, and Joy at beholding his numerous Family . . . . . . . . 130

- 5. An Unexpected Union . . . . . . . 130

- 6. Brotherless . . . . . . . . . 131

- 7. Complaint against a High Official . . . . . 132

- 8. Conflicting Duties . . . . . . . . 133

- 9. A haughty Usurper’s Petition to the King for Confirmation of his Position . . . . . . . 134

- 10. Too Poor to Entertain . . . . . . . 134

- 11. A Widow’s Sorrow and Devotion . . . . . 135

- 12. Mind not Idle Tales . . . . . . . . 136

- Book XI.—The Odes of Ts‘in.

- 1. Life at Court—Budding into Opulence and Gaiety . . 138

- 2. The Court-Hunt . . . . . . . . 139

- 3. The Absent Warrior-husband . . . . . . 139

- 4. Chasing the Phantom . . . . . . . 141 Edition: current; Page: [27]

- 5. The Ruler’s Return from the King’s Court after Promotion to Higher Rank . . . . . . . . 142

- 6. The Living buried with the Dead . . . . . 142

- 7. Out of Sight and Out of Mind . . . . . . 144

- 8. Comrades in War-time . . . . . . . 144

- 9. A Refugee Heir of Ts‘in assisted in his Rights . . . 145

- 10. Old Officials left in the Cold . . . . . . 146

- Book XII.—The Odes of Ch‘in.

- 1. A Pleasure-loving Official . . . . . . . 147

- 2. The Young Folks’ Holiday . . . . . . 148

- 3. Contentedness . . . . . . . . . 148

- 4. A Trysting-place . . . . . . . . 149

- 5. The Broken Tryst . . . . . . . . 149

- 6. A Warning . . . . . . . . . 150

- 7. Who lured my Love away? . . . . . . 150

- 8. Love’s Chain . . . . . . . . . 151

- 9. Duke Ling’s Visits to the Lady of Chu-lin . . . 151

- 10. Love’s Griefs . . . . . . . . . 152

- Book XIII.—The Odes of Kwai.

- Book XIV.—The Odes of Ts‘âu.

- Book XV.—The Odes of Pin.

- 1. Life in Pin in the Olden Time . . . . . . 160

- 2. The Nest, so hard to build, now Robbed . . . . 164

- 3. Song of the Troops on returning from the Eastern Campaign . . . . . . . . . 166

- 4. The Same . . . . . . . . . . 168

- 5. Comparisons . . . . . . . . . 169

- 6. Laments in the East at the Duke’s Recall . . . 169

- 7. The Duke’s Calmness under Calumny . . . . 170 Edition: current; Page: [28]

- Book I.—The Odes of Chow and the South.

- PART II. THE MINOR FESTAL ODES.

- Book I.

- 1. At the Royal Banquets . . . . . . . 173

- 2. Foreign Service . . . . . . . . 174

- 3. The Zealous Envoys . . . . . . . . 175

- 4. Brotherly Affection . . . . . . . . 176

- 5. Entertainment of Friends . . . . . . 177

- 6. Response of the King’s Guests . . . . . . 179

- 7. Song of the Troops during the Expedition against the Hin-Yun . . . . . . . . . 180

- 8. The Same . . . . . . . . . . 182

- 9. The Same.—Anxiety of the Wives at Home . . . 184

- 10. (Missing) . . . . . . . . . . 185

- Book II.

- 1. (Missing) . . . . . . . . . . 186

- 2. (Missing) . . . . . . . . . . 186

- 3. Song of the Guests at Country Feasts . . . . 186

- 4. (Missing) . . . . . . . . . . 187

- 5. The Welcome of Guests . . . . . . . 187

- 6. (Missing) . . . . . . . . . . 187

- 7. The Prince to his Ministers . . . . . . 188

- 8. (Missing) . . . . . . . . . . 189

- 9. The King to the Feudal Princes . . . . . 189

- 10. The Same.—At the Feast . . . . . . . 190

- Book III.

- 1. On the Presentation of the Vermilion Bow . . . 191

- 2. Joyous Greeting of a Good King . . . . . 192

- 3. Ki-fu’s Expedition against the Wild Northern Tribes . 193

- 4. Fang-shu’s Expedition against the Mân-King . . . 195

- 5. Grand Royal Hunt given in Honour of the Feudal Lords when at Court . . . . . . . . 197

- 6. Royal Hunt, with Guests and Friends . . . . 198

- 7. War and Peace . . . . . . . . . 199

- 8. The King’s Anxiety to be punctual at the Morning Audience . . . . . . . . . 200

- 9. A Statesman’s Lament on seeing the Apathy of his Brother-officers in a time of Anarchy and Trouble . 201

- 10. Random Thoughts on Common Things . . . . 202 Edition: current; Page: [29]

- Book IV.

- 1. Complaint of the Royal Guards on being sent to the Frontier . . . . . . . . . 203

- 2. “Fight with thy Wish the World to Flee” . . . 204

- 3. Disappointed Emigrants . . . . . . . 205

- 4. Inhospitable Kinsfolk . . . . . . . 206

- 5. On the Completion of a New Palace . . . . . 206

- 6. On the Prosperous Condition of the King’s Flocks and Herds . . . . . . . . . . 208

- 7. Complaint against King Yiu and his Chief Minister Yin . 210

- 8. The Kingdom verging towards Ruin . . . . 212

- 9. Evil Portents, Evil Days . . . . . . . 216

- 10. Further Lamentation, by an Underling at Court . . 218

- Book V.

- 1. Worthless Counsellors . . . . . . . 221

- 2. Laments and Warnings during an Evil Time . . . 223

- 3. Lament of a Defamed and Banished Prince . . . 224

- 4. A Slandered Official . . . . . . . . 227

- 5. Alienation of an Old Friend . . . . . . 228

- 6. Defamation . . . . . . . . . 230

- 7. Friendship veers with Fortune . . . . . . 232

- 8. The Orphan . . . . . . . . . 232

- 9. The neglected Eastern States . . . . . . 234

- 10. Evil Times . . . . . . . . . . 236

- Book VI.

- 1. An Overworked Official . . . . . . . 238

- 2. Advice to the Overburdened Official . . . . . 239

- 3. The Regrets of Foreign Service . . . . . . 240

- 4. The King loves Pleasure rather than Virtue . . . 241

- 5. At the Great Sacrifice in the Ancestral Temple . . 242

- 6. Husbandry and Ancestor-worship . . . . . 245

- 7. Thrift and Good Years . . . . . . . 247

- 8. The Same . . . . . . . . . . 248

- 9. Welcome to the Sovereign at the Eastern Capital by the Feudal Princes . . . . . . . . 249

- 10. The King’s Response . . . . . . . . 250

- Book VII.

- 1. Guest-song.—The King to the Feudal Princes . . . 252

- 2. Response of the Princes to the King . . . . . 253 Edition: current; Page: [30]

- 3. The King entertains his Relatives . . . . . 253

- 4. The Meeting of the Bride . . . . . . . 255

- 5. Slanderers at Court . . . . . . . . 256

- 6. Scenes at Wine-feasts . . . . . . . 256

- 7. Song of the Feudal Princes at a Royal Feast in Hâu . 259

- 8. The King’s Response . . . . . . . . 260

- 9. Like King, like People . . . . . . . 261

- 10. Beware the Discontented Angry King . . . . 262

- Book VIII.

- 1. Changed Times. The Heart goes back to the Old Capital 264

- 2. The Absent Husband . . . . . . . . 265

- 3. Song of the Troops after Shau’s Expedition to Sié . . 266

- 4. A Happy Meeting . . . . . . . . 267

- 5. Lament of a rejected Queen-consort . . . . 268

- 6. Unsoldier-like Complaints . . . . . . . 270

- 7. Drinking Song . . . . . . . . . 271

- 8. Toilsome Marches . . . . . . . . 272

- 9. Bad Times . . . . . . . . . . 272

- 10. The Soldier’s Hardships . . . . . . . 273

- Book I.

- PART III. THE GREATER FESTAL ODES.

- Book I.—The “Wăn Wong” Decade.

- 1. King Wăn, the Founder and Example of the Line of Chow . . . . . . . . . . 277

- 2. Further Eulogy of King Wăn . . . . . . 279

- 3. Origin of the House of Chow . . . . . . 281

- 4. In Praise of King Wăn . . . . . . . 283

- 5. His People’s Admiration . . . . . . . 284

- 6. His Virtues . . . . . . . . . 285

- 7. Rise of the Chow Dynasty . . . . . . . 286

- 8. Delight of the People on seeing the Magnificence with which King Wăn surrounded himself . . . 290

- 9. Eulogy of King Wu . . . . . . . . 291

- 10. Exploits of Wăn and Wu . . . . . . . 292

- Book II.—The “Shang Min” Decade.

- 1. How-tsih, the Progenitor of the Chow Family . . . 294

- 2. Festal Ode, on the King’s Entertainment of his Relatives 298 Edition: current; Page: [31]

- 3. Response of the Guests to the King . . . . . 299

- 4. At a Feast given to the Personators of the King’s Ancestors at a Sacrifice . . . . . . 300

- 5. Response . . . . . . . . . . 302

- 6. Duke Liu . . . . . . . . . . 303

- 7. Admonition to the King . . . . . . . 305

- 8. Further Admonition, under the guise of Congratulation 306

- 9. Censure of King Li’s Government . . . . . 308

- 10. Further Admonitions . . . . . . . 310

- Book III.—The “Tang” Decade.

- 1. Admonition of King Li . . . . . . . 313

- 2. Self-admonition . . . . . . . . . 316

- 3. Lament of the Earl of Juy . . . . . . 320

- 4. King Swăn’s Lamentation in a time of Drought and Famine . . . . . . . . . . 324

- 5. Eulogy of the Lord of Shin . . . . . . 327

- 6. Eulogy of Chung Shan-fu . . . . . . . 329

- 7. Eulogy of the Prince of Han . . . . . . 331

- 8. Hu of Shau’s Expedition against the Southern Tribes of the Hwai, and his Reward . . . . . . 334

- 9. King Swăn’s Expedition in Person against the Northern Hwai Tribes . . . . . . . . . 336

- 10. Pau-sze in Power . . . . . . . . 338

- 11. The Country in Collapse . . . . . . . 340

- Book I.—The “Wăn Wong” Decade.

- PART IV. FESTAL HYMNS AND SONGS.

- Book I.—The Hymns of Chow (First Section).

- 1. At the Sacrifice to King Wăn . . . . . . 345

- 2. Wăn’s Example . . . . . . . . . 345

- 3. His Statutes and Ordinances . . . . . . 346

- 4. The King to the Princes assisting him at Sacrifices . . 346

- 5. At the Shrine of King T‘ai . . . . . . 347

- 6. At the Shrine of King Ch‘ing . . . . . . 347

- 7. At the Shrine of King Wăn, as the Assessor of God . . 347

- 8. On King Wu’s Progress through his Dominions, after the Overthrow of Shang . . . . . . . 348

- 9. At Sacrifices in Honour of Kings Wu, Ch‘ing, and K‘ang 349

- 10. At Sacrifices in Honour of How-tsih . . . . . 350 Edition: current; Page: [32]

- Book II.—The Hymns of Chow (Second Section).

- 1. An Admonition addressed in the Spring to the Officers who presided over Agriculture . . . . . 351

- 2. Spring Song (in connection with a Sacrifice to King Ch‘ing) . . . . . . . . . . 352

- 3. Greeting of Guests representing at Court the two former Dynasties . . . . . . . . . 352

- 4. Harvest Home . . . . . . . . . 353

- 5. The Blind Musicians . . . . . . . . 353

- 6. At the Offering of the First Fish taken in the Spring . 354

- 7. King Wu’s Sacrifice to his deceased Father, assisted by the Feudal Princes . . . . . . . 354

- 8. The Feudal Princes come to assist King Ch‘ing in his Offerings to his Father Wu . . . . . . 355

- 9. Welcome to the Duke of Sung at the Court of Chow . 356

- 10. In Honour of the Achievements of King Wu . . . 357

- Book III.—The Hymns of Chow (Third Section).

- 1. At King Ch‘ing’s First Offering to his Father after the Period of Mourning . . . . . . . 358

- 2. King Ch‘ing’s Prayer to his deceased Father . . . 359

- 3. King Ch‘ing and his Counsellors . . . . . 359

- 4. The Resolve of King Ch‘ing after his First Error . . 360

- 5. Husbandry and Worship . . . . . . . 360

- 6. The Same . . . . . . . . . . 362

- 7. At the Sacrificial Feast . . . . . . . 363

- 8. In Honour of King Wu . . . . . . . 363

- 9. The Same . . . . . . . . . . 364

- 10. Wu’s Praise of his Father Wăn . . . . . 364

- 11. Royal Progress of Wu through his Dominions . . . 365

- Book IV.—The Festal Songs of Lu.

- Book V.—The Festal Odes of Shang.

- Book I.—The Hymns of Chow (First Section).