SCENE II.

miss lindon, lady alton.

miss lindon.

Who knocks so? what do you want, madam?

lady alton.

Answer me, madam. Does not Lord Murray come here sometimes?

Edition: current; Page: [25]

miss lindon.

What’s that to you? what right have you to ask me? am I a criminal, and you my judge?

lady alton.

I am your accuser. If my lord still visits you, if you encourage that wretch’s passion, tremble: renounce him, or you are undone.

miss lindon.

If I had a passion for him, your menaces, madam, would but increase it.

lady alton.

I see you love him; that the perfidious villain has seduced you; he has deceived you, and you brave me: but know, there is no vengeance which I am not capable of executing.

miss lindon.

Then, madam, know, I do love him.

lady alton.

Before I revenge myself I will astonish you. There, know the traitor, look at these letters he wrote to me: there is his picture too which he gave me; but let me have it back, or—

miss lindon.

[Giving her back the picture.

What have I seen? unhappy woman! madam—

miss lindon.

I no longer love him.

Edition: current; Page: [26]

lady alton.

Keep your resolution and your promise; know, he is inconstant, cruel, proud, the worst of characters.

miss lindon.

Stop, madam; if you continue to speak ill of him, I may relapse, and love him again. You are come here on purpose to take away my wretched life: that, madam, will easily be done.—Polly, ’tis all over; come and assist me to conceal this last and worst of all my miseries.

polly.

What is the matter, my dear mistress, where is your courage?

miss lindon.

Against misfortune, injustice, and poverty, there are arms that will defend a noble heart; but there is an arrow that always must be fatal.

[They go out.

SCENE III.

lady alton, wasp.

lady alton.

To be betrayed, abandoned for this worthless little wretch.

[To Wasp.

You, news-writer, have you done what I ordered you? have you employed your engines of intelligence, and found out who this insolent creature is that makes me so completely miserable?

Edition: current; Page: [27]

wasp.

I have fulfilled your ladyship’s commands, and have discovered that she is a Scotchwoman, and hides herself from the world.

lady alton.

Prodigious news indeed!

wasp.

I can find out nothing else at present.

lady alton.

What service then have you been of?

wasp.

When we discover a little, we add a little; and one little joined to another, makes a great deal. There’s a hypothesis for you.

lady alton.

How, pedant, a hypothesis!

wasp.

Yes, I suppose she is an enemy to the government.

lady alton.

Certainly, nothing can be worse inclined; for she has robbed me of my lover.

wasp.

You plainly see, therefore, that in troublesome times, a Scotchwoman, who conceals herself, must be an enemy to the state.

lady alton.

I can’t say I see it altogether so clearly, but I heartily wish it were so.

Edition: current; Page: [28]

wasp.

I would not lay a wager about it, but I’d swear to it.

lady alton.

And would you venture to affirm this before people of consequence?

wasp.

I have the honor of being related to many persons of the first fashion. I am intimate with the mistress of a valet de chambre to the first secretary of the prime minister: I could even talk with the lackeys of your lover, Lord Murray, and tell them that the father of this young girl has sent her up to London, as a woman ill disposed. Now observe, this might have its consequences, and your rival, for her bad intentions, might be sent to the same prison where I have so often been for my writings.

lady alton.

Good, very good: violent passions must be served by people who have no scruples about them. Let the vessel go with a full sail, or let it go to the bottom. You are certainly right; a Scotchwoman who conceals herself at a time when all the people of her country are suspected, must certainly be an enemy to the state. You are no fool, as you have been represented to me. I thought you had been only a smatterer on paper, but I see you have genius. I have already done something for you; I will do a great deal more. You must let me know everything that passes here.

wasp.

Let me advise you, madam, to make use of everything you know, and of everything you do not know. Edition: current; Page: [29] Truth stands in need of some ornament: downright lies indeed may be vile things, but fiction is beautiful. What after all is truth? a conformity with our own ideas; what one says is always conformable to the idea one has whilst one is talking; therefore, properly speaking, there is no such thing as a lie.

lady alton.

You seem to be an excellent logician, I fancy you studied at St. Omer’s. But go, only tell me whatever you discover, I ask no more of you.

SCENE V.

fabrice, mr. freeport.

[Dressed plainly, with a large hat.

fabrice.

Heaven be praised, Mr. Freeport, I see you safe returned: how are you since your voyage to Jamaica?

freeport.

Pretty well, I thank you, Mr. Fabrice, I have been very successful, but am much fatigued. [To the waiter.] Boy, some chocolate and the papers—one finds it more difficult to amuse oneself than to get rich.

fabrice.

Will you have Wasp’s papers?

freeport.

No: what should I do with such stuff? It is no concern of mine if a spider in the corner of a wall walks over his web to suck the blood of flies. Give me the Gazette! What public news have you?

fabrice.

None at present.

freeport.

So much the better; the less news the less folly. But how go your affairs, my friend? have you a good deal of business? who lodges with you now?

fabrice.

This morning an old gentleman came who won’t see anybody.

Edition: current; Page: [31]

freeport.

He’s in the right of it: three parts of the world are good for nothing, either knaves or fools, and as for the fourth, they keep to themselves.

fabrice.

This gentleman has not so much as the curiosity to see a charming young lady who is in the same house with him.

freeport.

There he’s wrong. Who is she, pray?

fabrice.

She is something more singular even than himself: she has now been with me these four months, and has never stirred out of her apartment: she calls herself Lindon, but I believe that is not her real name.

freeport.

I make no doubt but she’s a woman of virtue, or she would not lodge with you.

fabrice.

O she is more than you can conceive; beautiful to the last degree, greatly distressed, and the best of women. Between you and me she is excessively poor, but of a high spirit and very proud.

freeport.

If that be the case she is more to blame even than your old gentleman.

fabrice.

By no means: her pride is an additional virtue. She denies herself common necessaries, and at the Edition: current; Page: [32] same time would let nobody know she does: works with her own hands to get money to pay me; never complains, but hides her tears: it is with the utmost difficulty I can persuade her to expend a little of her money, due for rent, on things she really wants; and am forced to make use of a thousand arts before she will suffer me to assist her. I always reckon what she has at half the price it cost me, and when she finds it out, there is always a quarrel between us, which indeed is the only quarrel we have ever had: in short, sir, she is a miracle of virtue, misfortune, and intrepidity: she frequently draws from me tears of tenderness and admiration.

freeport.

You are naturally tender; I am not. I admire none, though I esteem many: but I will see this woman; I am a little melancholy, and she may divert me.

fabrice.

O sir, she scarcely ever receives any visitors. There is a lord indeed who comes now and then to see her, but she will never speak to him unless before my wife. He has not been here for some time, and now she lives more retired than ever.

freeport.

I love retirement too, and hate a crowd as much as she can: I must see her, where is her apartment?

fabrice.

Yonder: even with the coffee-room.

Edition: current; Page: [33]

freeport.

I say I must: why not go into her chamber? bring in my chocolate and the papers. [Pulls out his watch.] I have not much time to lose, for I am engaged at two.

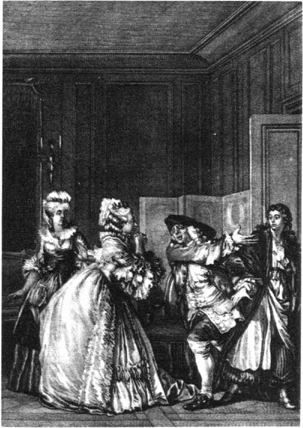

SCENE VI.

miss lindon, [frightened, Polly following her.]

freeport, fabrice.

miss lindon.

My God! who is this? sir, you are extremely rude; I think you might have shown more respect to my sex than thus to intrude on my retirement.

freeport.

You will pardon me, madam, [To Fabrice] bring me the chocolate.

fabrice.

Yes, sir, with the lady’s consent.

freeport.

[Seats himself near a table, reads the newspaper, and looks up to Miss Lindon and Polly, takes off his hat, and puts it on again.

polly.

This gentleman seems pretty familiar.

freeport.

Why won’t you sit down, madam? you see I do.

Edition: current; Page: [34]

miss lindon.

Which I think, sir, you ought not to do. I am astonished, sir: I never receive visits from strangers.

freeport.

A stranger, madam! I am very well known; my name’s Freeport, a merchant, and rich: inquire of me on ’Change.

miss lindon.

Sir, I know nobody in this country, I should be obliged to you if you would not intrude on a person to whom you are an utter stranger, and to whom as a woman you should have shown more respect.

freeport.

I don’t mean to incommode you, madam: be at your ease, as I am at mine; you see I am reading the news, take up your tapestry, or drink chocolate with me, or without me, just as you please.

polly.

This is an original!

miss lindon.

Good heaven! what a visit! and my lord not come. This whimsical fellow distracts me, and I don’t know how to get rid of him. How could Fabrice let him in! I must sit down.

[She sits down, and works, chocolate is brought in; Freeport takes a dish without offering her any; he sips, and talks by turns.

freeport

Hark’ee, madam, I hate compliments, I have heard one of the best of characters of you: you are Edition: current; Page: [35] poor and virtuous, but they tell me you are proud; that’s a fault.

polly.

And pray, sir, who told you all this?

freeport.

The master of this house, who is a very honest man, and therefore I believe him.

miss lindon.

O sir, ’tis all a fable; he has deceived you; not indeed with regard to pride, which always accompanies true modesty: nor as to virtue, which is my first duty; but with regard to that poverty of which he suspects me. Those who want nothing can never be poor.

freeport.

You don’t stick to truth, which is even a worse fault than being proud: I know better, I know you are in want of everything, and sometimes deny yourself so much as a dinner.

polly.

That’s by order of the doctor.

freeport.

Hold your tongue, hussy, do you pretend to give yourself airs too?

freeport

In a word, whether you are proud or not, is nothing to me. I have made a voyage to Jamaica that has brought me in five thousand pounds: now, you must know, it is a law with me, and ought to be Edition: current; Page: [36] a law with every good Christian, always to give away a tenth part of what I get: it is a debt which I owe to the unfortunate. You are unhappy, though you won’t acknowledge it. There’s five hundred pounds for you: now, remember, you’re paid: let me have no curtseys, no thanks, keep the money and the secret.

[Throws down a large purse on the table.

polly.

In faith this is more original still.

miss lindon.

[Rising.

I never was so astonished in my life—alas! how everything conspires to humble me! what generosity! and yet what an affront!

freeport.

[Reading the news and drinking his chocolate.

This impertinent writer! a ridiculous fellow to talk such nonsense with an air of consequence—“The king is arrived: he makes a most noble figure, being extremely tall.” The blockhead! what signifies it whether he is tall or short? could not he have told us the plain fact?

miss lindon.

[Coming up to Freeport.

Sir—

miss lindon.

What you have done, sir, surprises me still more than what you said: but I cannot possibly accept the Edition: current; Page: [37] money, as it may not, perhaps, ever be in my power to repay it.

freeport.

Who talks of repaying it?

miss lindon.

I thank you, sir, for your goodness, from the bottom of my heart: you have my sincere acknowledgments, my admiration; I can no more.

polly.

You are more extraordinary than the gentleman himself. Surely, madam, in the condition you are in, deserted by all the world, you must have lost your senses to refuse an unexpected succor, thus offered you by one of the most generous, though whimsical and absurd men I ever met with.

freeport.

What do you mean by that, madam! whimsical and absurd!

polly.

If you won’t accept of it for your own sake, take it for mine. I have served you in your ill-fortune, and have some right to partake of the good: in short, sir, this is no time to dissemble, we are in the utmost distress; and if it had not been for our kind landlord, must have perished with cold and hunger. My mistress concealed her condition from all those who might have been of service to us: you became acquainted with it in spite of her: in spite of herself, therefore, oblige her to accept of that which heaven hath sent her by your generous hand.

miss lindon.

Dear Polly, you will ruin my honor.

Edition: current; Page: [38]

polly.

You, my dear mistress, would ruin yourself by your folly.

miss lindon.

If you love me, consider my reputation. I shall die with shame.

freeport.

[Reading.

What are these women prating about?

polly.

And if you love me, madam, don’t oblige me to perish with hunger.

miss lindon.

O Polly, what think you my lord would say, if still he loves me? could he believe me capable of such meanness? I always pretended to him that I wanted nothing; and shall I receive a present from another, from a stranger?

polly.

Your pretence was wrong, and your refusal still more so: as to my lord, he’ll say nothing about it, for he has deserted you.

miss lindon.

My dear Polly, by our sorrows I entreat you, do not let us disgrace ourselves: contrive in some way to excuse me to this strange man, who means well, though he is so rude and unpolished: tell him, when an unmarried woman accepts such presents, the world will always suspect she does it at the expense of her virtue.

Edition: current; Page: [39]

freeport.

[Reading.

What does she say?

polly.

[Coming close to him.

O sir, something mighty ridiculous; she talks of the suspicions of the world, and that an unmarried woman—

freeport.

Is she unmarried then?

polly.

Yes, sir, and I too

freeport.

So much the better. So she says that an unmarried woman—

polly.

Cannot take a present from a man—

freeport.

She does not know what she says. Why am I to be suspected of a dishonest purpose, because I do an honest action?

polly.

Do you hear him, madam?

miss lindon.

I hear, and I admire him, but am still resolved not to accept it: they would say I loved him; that villain. Wasp, would certainly report it, and I should be undone.

polly.

[To Freeport.

She is afraid, sir, you are in love with her.

Edition: current; Page: [40]

freeport.

In love with her! how can that be, when I know nothing of her? indeed, madam, you may make yourself easy on that head; and if perchance some years hence I should fall in love with you, and you with me, well and good; as you determine, I shall determine also; and if you think no more of it, I shall think no more of it; if you tell me I am disagreeable to you, you will soon be so to me; if you desire not to see me, you shall never see me again; and if you desire me to return, I will.

[Pulls out his watch.

So fare you well. I have a little business at present. Madam, your, servant.

miss lindon.

Your servant, sir, you have my esteem and my gratitude; but take your money with you, and once more spare my blushes.

freeport.

The woman’s a fool.

miss lindon.

Mr. Fabrice, Mr. Fabrice, for heaven’s sake come and assist me.

fabrice.

[Coming in a violent hurry.

What’s the matter, madam?

miss lindon.

[Giving him the purse.

Here, take this purse: the gentleman left it by mistake, give it him again, I charge you; assure him of my esteem, and remember I want no assistance from any one.

Edition: current; Page: [41]

fabrice.

[Taking the purse.

O Mr. Freeport, I know you by this generous action; but be assured this lady means to deceive you: she is really in want of this.

miss lindon.

’Tis false: and is it you, Mr. Fabrice, who would betray me?

fabrice.

I will obey you, madam.

[Aside to Freeport.

I will keep this money; it may be of service to her without her knowing it. My heart bleeds to see such virtue joined to such misfortunes.

freeport.

I feel for her too, but she is too haughty: tell her it is not right to be proud. Adieu.

SCENE VII.

miss lindon, polly.

polly.

Well, madam, you have made a fine piece of work of it; heaven graciously offered you assistance, and you resolve to perish in indigence; I too must fall a sacrifice to your virtue, a virtue which is not without its alloy of vanity: that vanity, madam, will destroy us both.

miss lindon.

Death is all I have to wish for: Lord Murray no longer loves me; he has left me these three days; Edition: current; Page: [42] he has loved my proud and cruel rival; perhaps, he loves her still. I was to blame to think of him, but ’tis a crime I shall not long be guilty of.

[She sits down to write.

polly.

She seems in despair, alas! she has but too much reason to be so; her condition is far worse than mine: a servant has always some resource, but a woman like her can have none.

miss lindon.

[Folding up her letter.

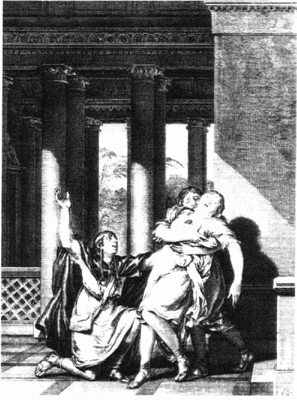

’Tis no great sacrifice. There, Polly, when I am no more, carry that letter to him—

polly.

What says my dear mistress?

miss lindon.

To him who is the cause of my death. I have recommended you to him, perhaps he may comply with my last request: go, Polly, [embracing her] and be assured, that amongst all my misfortunes, that of not being able to recompense you as you deserve, is not the least which this wretched heart has experienced.

polly.

O my dear mistress, I cannot refrain from tears, you harrow up my soul: what is your dreadful purpose? what means this letter? God forbid I should ever deliver it! [she tears the letter.] Alas! madam, why would not you open your heart to Lord Murray? perhaps your cold reserve has disgusted him.

Edition: current; Page: [43]

miss lindon.

Perhaps so, indeed: my eyes are open now, I must have offended him: but how could I disclose my condition to the son of him who ruined my father and family?

polly.

How, madam! was it my lord’s father who—

miss lindon.

Yes, it was he who persecuted my father, had him condemned to death, deprived us of our nobility, and took away everything from us: left as I am without father, mother, or fortune, I have nothing but my reputation and my fatal love. I ought to detest the son of Murray: misfortune, that still pursues me, brought me acquainted with him. I have loved him, and I ought to suffer for it.

polly.

O madam, you grow pale, your eyes are dim.

miss lindon.

May grief perform that office for me, which sword or poison—

polly.

Help here, Mr. Fabrice, help: my mistress faints.

fabrice.

Help, help here! where are ye all, my wife, my servants, come down: tell the gentlemen above—help here—

[Fabrice’s wife, her maids, and Polly, carry off Miss Lindon into her chamber.

Edition: current; Page: [44]

miss lindon.

[As she is going out.

Why will ye bring me back to life again? let me die in peace.