CHRESTOMATHIA:

BEING A COLLECTION OF PAPERS, EXPLANATORY OF THE DESIGN OF AN INSTITUTION, PROPOSED TO BE SET ON FOOT UNDER THE NAME OF THE CHRESTOMATHIC DAY SCHOOL, OR CHRESTOMATHIC SCHOOL, FOR THE EXTENSION OF THE NEW SYSTEM OF INSTRUCTION TO THE HIGHER BRANCHES OF LEARNING, FOR THE USE OF THE MIDDLING AND HIGHER RANKS IN LIFE.

FIRST PUBLISHED IN 1816

Edition: current; Page: [ii]INTRODUCTION BY THE EDITOR.

Mr Bentham was one of the first to recognise the extraordinary improvement in the method of instruction developed by Mr Lancaster and modified and extended by Dr Bell. The account of the results attending its application to the acquisition of language, given by several eminent teachers from their own actual trial of it, and more especially the statements of Dr Russel, then Head-master of the Charter-house School, and of Mr Pillans and Mr Gray, masters of the High School of Edinburgh, (Appendix No. 2. and 3. pp. 59 and 61)—made a strong impression on Mr Bentham’s mind. If it were true, as stated by Dr Russel, that since he had introduced into the Charter-house School books prepared on the simple principle of the Madras System, no boy had ever passed a sentence of which he was ignorant, nor been flogged on the ground of his learning; if it were true, as stated by Mr Gray, that since he had introduced this system into his school, his whole class had gained a more extensive knowledge of the Latin language than he had ever known on any former occasion; that not a single boy had failed; that it had enabled him entirely to abolish corporal punishment; that it had animated his whole school with one spirit, making them all advance in the intellectual career with the like ardour, and though not with equal success, without a single failure, and that Mr Lancaster had put into his hands an instrument which had enabled him to realize his fondest visions in his most sanguine mood;*—if such results were obtained by the application of this instrument to the acquisition of Latin and Greek, what, said Mr Bentham, may not be expected from its application to the whole field of knowledge? Are there not several branches to which it might be applied with still greater advantage than to language; and is there one which does not afford the promise of at least equal success?

Mr Bentham thought that these questions must be answered in the affirmative, and the great interest which he naturally took in this subject, was strengthened by the desire expressed by some friends of his, among whom were several statesmen and men of wealth, that the experiment should be tried; that a Day School should be opened for the children of the middle and higher classes, in which the principles of the new method should be applied, not only to the teaching of language, but of all the other branches of instruction which are ordinarily included in the curriculum of the highest schools. With his usual ardour, Mr Bentham immediately proposed that the school-house should be erected in his own garden, and that he himself should take a chief part in the superintendance of the school; at the same time his opulent friends agreed to supply the requisite funds.

But these arrangements having been determined on, Mr Bentham now saw that the most difficult part of the undertaking still remained to be accomplished. It was necessary to bring out the principles of the new method more distinctly than had yet been done, and to shape them into so many instruments, each capable of being applied, by ordinary hands, to its specific use: it was equally necessary to review the whole field of knowledge in order to ascertain to what branches of instruction these instruments might be applied with the greatest promise of success; and to what, if any, their application should not be attempted.

The accomplishment of such a project was well calculated to call forth all the energies of Mr Bentham’s mind, and he immediately applied himself to the work. In the meantime, this new school and the devotion of Mr Bentham to the development of the plan of it, became matter of conversation among the philosophers, statesmen, and friends to education of the day. The determination which had been come to, to exclude Theology from the curriculum of instruction, on the ground that its inclusion would be pregnant with exclusion, was also very generally discussed. Alarm was taken at the rumour of this omission; and clerical influence was brought to bear upon the minds of some of the more opulent persons who had encouraged the project, with the ultimate result of causing them to abandon it. However he might regret the loss of support which had been so readily and confidently assured to him, Mr Bentham was not on that account to be turned aside from his purpose. He resolutely persevered in the completion of his part of the compact; and hence although there is no school in the garden of Queen Square Place, yet we have the Chrestomathia.

Whatever other useful purposes may result from the intellectual labour which has been spent upon the production of these papers, it will be found that they are capable of affording special and invaluable assistance to two different classes of persons. First to him who is desirous of developing and strengthening his own intellectual faculties, and of rendering his Edition: current; Page: [iii] mind capable of making some progress in the field of original thought and invention, and of extending the domain of science. Such a person should give his days and nights to the study of the instrument described in Appendix, p. 101—128, (and further illustrated in the work on Logic, p. 253 et seq.,) and to actual practice with it. There is no intellectual gymnasium from exercise in which a powerful mind will derive so great an accession of strength.

Secondly, to him who is desirous of improving the character of elementary school-books. In the first number of the Westminster Review, in an elaborate article written nearly twenty years ago, on the Chrestomathia, after an attempt to show, that, for perfect instruction in all the physical sciences, as well as in geometry, algebra, and language, nothing is requisite but elementary books adapted to the new system, the writer asks whether “it be too much to hope, that there are men of science, whose benevolence will induce them to undertake a labour which, humble as it may appear, can be performed only by a philosophical mind which has thoroughly mastered the art and science to be taught. Can any scholar be more nobly employed than in writing such a book on language? or any natural, moral, or political philosopher, than in disclosing to the youthful understanding, in the most lucid order, and in the plainest terms, the profound, which are always the simple, principles of his respective science.”

Since Mr. Bentham wrote, the perception, in the public mind, has become more clear and strong, of the folly of consuming more than three-fourths of the invaluable time appropriated to education, “in scraping together,” as Milton expresses it, “so much miserable Greek and Latin,” by persons of the middle classes, to whom it is of no manner of use; to whose pursuits it bears no kind of relation; who, after all, acquire it so imperfectly, as to derive no pleasure from the future cultivation of it; who invariably neglect it as soon as they are released from the authority of school; and, in the lapse of a few years, allow every trace of it to be obliterated from the memory. Not only is it now generally admitted, that the subject-matter of instruction for these classes should consist of the physical sciences, as well as of language, but it is, moreover, beginning to be perceived, that some advantages would result to the community from opening the book of knowledge to the very lowest of the people; that everything which it is desirable to teach even the masses, is not comprehended in the facts, that there is a devil, a hell, a so-called heaven, a Sunday, and a church, but that there are things worthy of their attention connected with the objects of this present world,—the properties and relations of the air they breathe, the soil they cultivate, the plants they rear, the animals they tend, the materials they work upon in their different trades and manufactures,—the instruments with which they work,—the machinery by which a child is able to produce more than many men, and a single man to generate, combine, control, and direct a physical power superior to that of a thousand horses. There is a growing conviction, that the communication of knowledge of this kind to the working classes would make them better and happier men; and that the possession of such knowledge by these classes would be attended with no injury whatever to any other class. The want of elementary books is therefore becoming every day more urgent; nothing has yet been done to supply them; and yet here, in the Chrestomathia, there is a mine from which any competent hand might dig the material, and fashion the instrument.

The comprehensiveness of the view taken by one and the same mind, of every subject included in such a work as the Chrestomathia, cannot be expected to be equal; nor were all the subjects treated of by Mr Bentham left by him in a state which he regarded as complete. The papers which relate to Geometry and Algebra, in particular, appeared to require revision; and the Editor thought it right to place them for that purpose in the hands of a universally acknowledged master of these sciences. After a careful examination of these manuscripts by this gentleman, they were returned to the Editor, with the following observation:—“That although much has been done in relation to these subjects, on many of the points treated of by Mr Bentham, since the time at which he wrote, or so shortly before it, that he could not know of it; and though his views of first principles were unmatured by the consideration of their highest results, yet the publication of these papers, without alteration or omission, is still desirable, as exhibiting many useful, and several original, trains of thought; and offering many suggestions, of which, though some are imperfect, and others obsolete, the greater number may furnish matter for reflection even to those who have made the exact sciences more their special study than did Mr Bentham.”

Several passages in this work will appear obscure, and a few perhaps unintelligible, owing to the occurrence in the manuscript of some words, so illegible, that those best acquainted with Mr Bentham’s hand-writing have been unable to decypher them. The only liberty taken with the manuscript has been that of supplying, in these comparatively few cases, the best conjectural word that could be imagined. It has been deemed a duty to publish these papers in the state in which Mr Bentham left them, it being no part of the office of an Editor to intermeddle with the thoughts and expressions of the author.

CONTENTS.

- Prefaces to First Edition - - - - Page 5

- Notes to Chrestomathic Tables.

- Notes to Table I. - - - - 8

- Advantages derivable from Learning or Intellectual Instruction - - - - ib.

- Objections answered - - - - 16

- Relations of the proposed to the existing great Schools, Universities, and other didactic Institutions - - - - - - 21

- Obstacles and Encouragements - - 22

- Grounds of Priority - - - - 25

- Stages of Instruction - - - - 28

- Notes to Table II.

- Notes to the Exercises - - - - 44

- Notes to the Principles - - - - 46

- APPENDIX.

- No. I. Chrestomathic Proposal, being a proposal for erecting by subscription, and carrying on by the name of the Chrestomathic School, a Day-School for the extension of the new system to the higher branches of Instruction and ranks in life - - 54

- No. II. Successful Application of the New System to language-learning in the High School of Edinburgh, as reported by Professor Pillans - - - - - 59

- No. III. Successful Application of the New System to language-learning in the High School of Edinburgh, as reported by Mr Gray 61

- No. IV. Essay on Nomenclature and Classification.

- Section 1. Plan, - - - - 63

- 2. Purposes to which a denomination given to a branch of Art and Science may be applied, - - - - 64

- 3. Imperfections incident, - 66

- 4. Inaptness of the appellatives Natural History, Natural Philosophy, and Mathematics - - - - 68

- 5. Cause or origin of this inaptitude - - - - 70

- 6. Course for framing the best system of Encyclopedical Nomenclature - - - 71

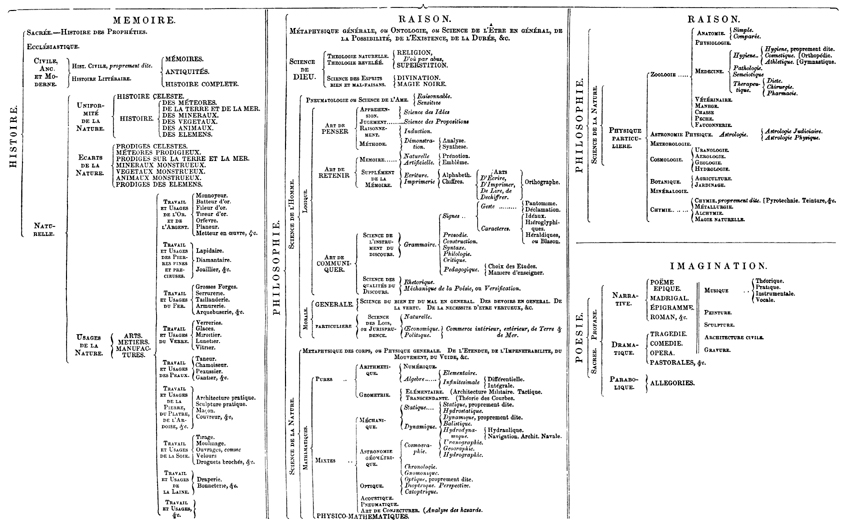

- 7. D’Alembert’s Encyclopedical Map—its imperfections - 73

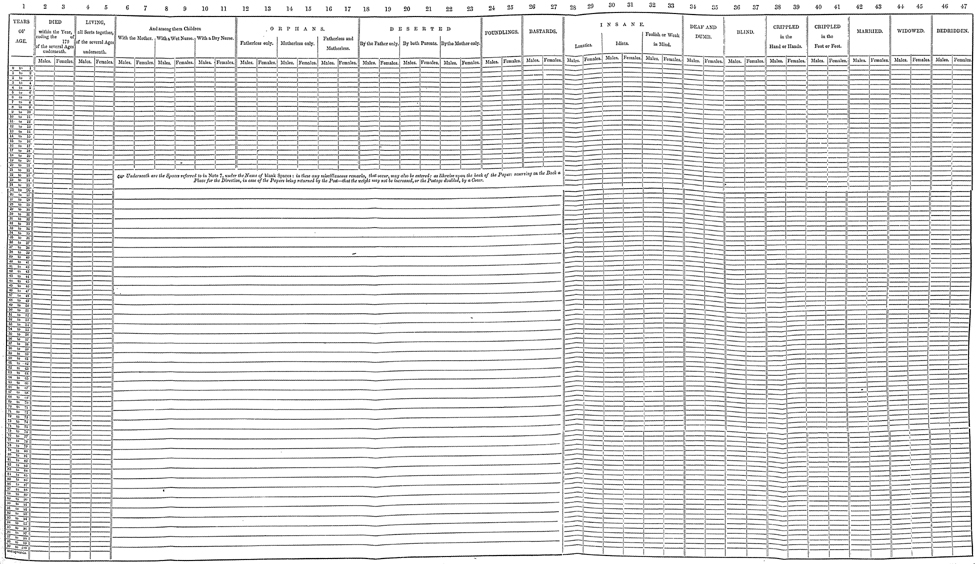

- 8. Specimen of a new Encyclopedical Sketch, with a correspondent Synoptic Table or Diagram - - - 82

- 9. Explanations relative to the above Sketch and Table - 95

- 10. Uses of a Synoptic Encyclopædical Table or Diagram 98

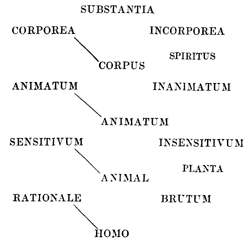

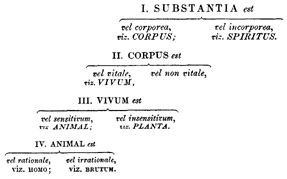

- Section 11. Mode of Division should, as far as may be, be exhaustive—Why? - - - 101

- 12. Test of All-comprehensiveness in a division - - 102

- 13. Exhaustiveness, as applied by Logical Division—the idea whence taken - - 110

- 14. Imperfection of the current conceptions relative to Exhaustiveness and Bifurcation 112

- 15. Watt’s Logic, - - - 114

- 16. Reid and Kaimes, - - 115

- 17. Process of Exhaustive Bifurcation—to what length may and shall it be carried? - 116

- 18. How to plant a Ramean Encyclopædical Tree on any given part of the field of art and science - - - 118

- 19. Logical mode of Division—its origin explained and illustrated - - - - 121

- 20. Proposed new names—in what cases desirable—in what likely to be employed - - 126

- No. V. Analytical Sketch of the several Sources of Motion, with their corresponding Primum Mobiles - 128

- No. VI. Sketch of the Field of Technology - - - - - - 148

- No. VII. Hints towards a System and Course of Technology from Bishop Wilkins’ Logical Work, published by the Royal Society, A° 1668, under the title of “An Essay towards a real character and a Philosophical Language” - - - - - - 150

- No. VIII. New Principles of Instruction, proposed as applicable to Geometry and Algebra, principally for the purpose of supplying to those superior branches of learning, the exercises already applied with so much success to Elementary Branches 155

- No. IX. Hints towards the Composition of an Elementary Treatise on Universal Grammar.

FIRST PREFACE TO THE FIRST EDITION.

From the determination to employ the requisite mental labour, in addition to the requisite pecuniary means, in the endeavour to apply the newly invented system of instruction, to the ulterior branches of useful learning, followed the necessity of framing a scheme of instruction for the school, in which it was proposed that the experiment should be made.

From the necessity of framing this scheme, followed the necessity of making a selection among the various branches of learning—art-and-science-learning, as well as language-learning included.

From the necessity of making this selection, followed the necessity of taking a comprehensive—howsoever slight, and unavoidably hasty—survey, of the whole field.

In the course of this survey, several ideas presented themselves, of which some had for some forty or forty-five years been lying dormant, others were brought into existence by the occasion: and, which, appearing to afford a promise of being, in some degree, capable of being rendered subservient to the present design, were—after inquiry among books and men—supposed to have in them more or less of novelty, as well as use.

Introduced, though necessarily in a very abridged form, into the present collection of papers, they will, it is hoped, be productive of one effect—nor will it be deemed an irrelevant one—viz. the contributing to produce—in the breasts of the persons concerned, whethe in the character of parents and guardians, or in the character of contributors to the fund necessary for the institution of the proposed experimental course, the assurance that, on the part of the proposed conductors, howsoever it may be in regard to ability, neither zeal nor industry are wanting: and that, having undertaken for the applying, to this, in some respects superior purpose, according to the best of their ability, the powers of the newly invented and so universally approved intellectual machine—their eyes, their hearts, and their hands will continue open, to every suggestion, that shall afford a prospect, of being in any way contributory, to so universally desirable an effect.

In regard to such part of Table II. as regards the principles of the New Instruction System, though of the matter itself, no part worth mentioning belongs to the author of the other parts, nor to any person other than those benefactors of mankind, whose title to it stands acknowledged by a perpetual chain of references—yet, in respect of the arrangement, which is altogether new, and the compression, which is studiously close—such is the convenience, which, it is hoped, will be found derivable from the summary, which (though for an ulterior and somewhat different purpose) is here given of it, that—even were this the only use of that summary—the labour here expended, though upon a soil already so rich, would not, it is hoped, be regarded as having been altogether unprofitably bestowed.

SECOND PREFACE TO THE FIRST EDITION.

In the Table of Contents, to wit in that part of it which regards the Appendix, the number of articles mentioned will be observed to be ten. Of these no more than four can at the present conjuncture be delivered. They have, however, been all of them written at least once over: and the fifth, which is longer than all the following ones put together, is completed for the press, and wants not much of being all printed. The rest, to fit them for the press, want nothing but to be revised.* How long, or how short soever, may be the portion of time still requisite for giving completion to the work, the purpose for which it was written admitted not ulterior delay, in the publication of such part of it as was in readiness. With Edition: current; Page: [6] reference to the main purpose, it may, however, without any very material misconception, be considered as complete. In what is now made public will be found everything that can be considered as essential to the development of the plan of instruction. What remains is little more than what seemed necessary to give expression to a few ideas of the author’s own, relative to the subjects which will be found mentioned: ideas, so far as he knows, peculiar to himself, and which had presented themselves as affording a hope of their giving, in different ways, more or less additional facility to the accomplishment of the useful purposes in view.

Time enough for their taking their chance for helping to recommend the plan, to the notice of such persons to whom, in the hope of obtaining their pecuniary assistance, the plan will come to be submitted, it has not been possible for him to get it in readiness: but, from the general intimation given of the topics in the Table of Contents, may be seen what is in view; and from the first Preface, together with what has just been said in this second, what progress has been made in it. Whatsoever assistance it may be found capable of contributing towards the accomplishment of the general object, thus much the reader may be assured of, viz. that, if life and faculties continue, everything that has thus been announced will be before the public in a few months, and long enough before the course of instruction can have placed any of its scholars in a condition to reap any benefit that may be found derivable from it.

Of this Appendix, No. I. is occupied by a paper there styled Chrestomathic Proposal. In concert with the public-spirited men, with whom the idea of the enterprise had originated, it was drawn up, at a time when it was thought that, by the circulation of that paper, such a conception of the plan might be afforded as might be sufficient for the obtaining such assistance as, either from pecuniary contributions, or from additional managing hands, should be found requisite. After the paper was printed in the form and in the place in which it will be seen, intervening incidents, and ulterior considerations having suggested various particulars, as being requisite—some to be added, others to be substituted—the task of drawing up a paper for this purpose, was undertaken by other hands. It will be seen, however, that the plan of instruction referred to being exactly the same, what difference there is turns upon no other point than some of those which relate to the plan of management: and even of these matters, as contained in the more recent paper in question, several will, it is believed, be found to receive more or less of explanation from the anterior paper, which, as above, will be seen reprinted in these pages.

On the length of the interval—which, between the printing of the Preface, and the sending to the press this Supplement to it, has elapsed—the author, though he has the satisfaction of thinking the commencement of the enterprise has not been retarded by it, cannot, on his own account, reflect without regret, nor altogether without shame. Under this pressure, his good fortune has, however, as will presently be seen, brought to him a consolation, superior to everything to which his hopes could have raised themselves.

The delay in question has had for its source the paper which, in the contents of the Appendix to this tract, will be seen distinguished by No. V. [IV.], and to which, at the top of each page, for a running title, the words, On Nomenclature and Classification, or On the Construction of Encyclopedical Trees—had been destined, but came too late to be employed. Of the number of sections which it contains, all but the 12th had been completed for the press, and all down to the 12th exclusive been delivered from the press—when, from a recent publication, a passage, of which what follows is a reprint, was put into the author’s hands.

In it the reader will observe—and from an official hand of the first celebrity—a certificate of difficulty, indeed of something more than difficulty, applied to the very work, of which, in and by this same 12th section, the execution has been attempted. It will be found, in Volume I. of the Appendix to the new edition, termed, on the cover, the 4th and 5th, of the Edinburgh Encyclopedia Britannica: date on the cover, December 1815. It commences at the very commencement of the Preface, which has for its title, “Preface to the First Dissertation, containing some critical remarks on the Discourse prefixed to the French Encyclopedie.”

“When I ventured,” says Mr Stewart, “to undertake the task of contributing a Preliminary Dissertation to these supplemental volumes of the Encyclopædia Britannica, my original intention was, after the example of D’Alembert, to have begun with a general survey of the various departments of human knowledge. The outline of such a survey, sketched by the comprehensive genius of Bacon, together with the corrections and improvements suggested by his illustrious disciple, would, I thought, have rendered it comparatively easy to adapt their intellectual map to the present advanced state of the sciences; while the unrivalled authority which their united work has long maintained in the republic of letters, would, I flattered myself, have softened those criticisms which might be expected to be incurred by any similar attempt of a more modern hand. On a closer examination, however, of their labours, I found myself under the necessity of abandoning this design. Doubts immediately occurred to me with respect to their logical views, and soon terminated in a conviction, that these views are radically and essentially erroneous. Instead, therefore, of endeavouring to give additional currency to speculations which I conceived to be fundamentally unsound, Edition: current; Page: [7] I resolved to avail myself of the present opportunity to point out their most important defects;—defects which I am nevertheless very ready to acknowledge, it is much more easy to remark than to supply. The critical strictures, which in the course of this discussion I shall have occasion to offer on my predecessors, will, at the same time, account for my forbearing to substitute a new map of my own, instead of that to which the names of Bacon and D’Alembert have lent so great and so well-merited a celebrity; and may perhaps suggest a doubt, whether the period be yet arrived for hazarding again, with any reasonable prospect of success, a repetition of their bold experiment. For the length to which these strictures are likely to extend, the only apology I have to offer is, the peculiar importance of the questions to which they relate, and the high authority of the writers whose opinions I presume to controvert.”

In the above-mentioned No. V. [IV.] the experiment thus spoken of will be seen hazarded: and, to help to show the demand for it, a critique on the Map, for which Bacon found materials and D’Alembert the graphical form, precedes it: a critique, penned by one, in whose eyes the most passionate admiration, conceived in early youth, afforded not a reason for suppressing any of the observations of an opposite tendency, which, on a close examination, have presented themselves to maturer age.

By an odd coincidence, each without the knowledge of the other, the Emeritus Professor and the author of these pages will be seen occupied in exactly the same task. The one quitted it, the other persevered in it: whether both, or one alone—and which, did right, the reader will have to judge. For an experiment, from which no suffering can ensue, unless it be to the anima vilis, by which it is made, no apology can be necessary. Having neither time nor eyes, for the reading of anything but what is of practical necessity, the above passage contains everything which the author will have read, in the book from which it is quoted, before the number in question is received from the press. To some readers—not to speak of instruction—it may perhaps be matter of amusement, to see in what coincident and in what different points of view, a field so vast in its extent has been presenting itself to two mutually distant pair of eyes,—and in what different manners it has accordingly been laboured in by two mutually distant pair of hands. To the author of these pages, in the present state of things, from any such comparison, time for the instruction being past, nothing better than embarrassment could have been the practical result: for the departed philosophers had already called forth from his pen a load already but too heavy for many a reader’s patience.

On casting upon the ensuing pages a concluding glance, the eye of the author cannot but sympathize with that of the reader, in being struck with the singularity of a work, which, from the running titles to the pages, appears to consist of nothing but Notes. Had the whole together—text and notes—been printed in the ordinarily folded or book form, this singularity would have been avoided. But in the view taken of the matter by the author, it being impossible to form any tolerably adequate judgment on, or even conception of, the whole, without the means of carrying the eye, with unlimited velocity, over every part of the field,—and thus at pleasure ringing the changes upon the different orders, in which the several parts were capable of being surveyed and confronted,—hence the presenting them all together upon one and the same plane—or, in one word, Table-wise—became in his view a matter of necessity. But the matter of the text being thus treated Table-wise, to print it over again in the ordinary form would, it seemed, have been making an unnecessary addition to the bulk of the work. Hence it is that, while the Notes alone are printed book-wise, the Text, to which these Notes make reference, and without which there can be little expectation of its being intelligible, must be looked for in the two first of the Tables which will accompany this work—and which, out of a larger number, are the only ones that will accompany this first part of it.

Hence it happens, that, on pain of not extracting any ideas from the characters over which he casts his eye, the reader will find the trouble of spreading open the Tables, as he would so many maps, a necessary one. Even this trouble, slightly as it may be felt under the stimulus of any strongly exciting interest, will—as is but too well known to the Author, from observation, not to speak of experience—be but too apt to have the effect of an instrument of exclusion, on those minds, of which there are so many, of which the views extend not beyond the amusement of the moment. But, as above, whatsoever may be the risk attached to the singularity thus hazarded, it has presented itself as an unavoidable one.

CHRESTOMATHIC (a) INSTRUCTION TABLES. TABLE I.

Showing the several branches of INTELLECTUAL INSTRUCTION, included in the aggregate course, proposed to be carried on in the Chrestomathic school: together with the several STAGES, into which the course is proposed to be divided: accompanied with a brief view of the ADVANTAGES derivable from such Instruction: together with an intimation of the REASONS, by which the ORDER OF PRIORITY, herein observed, was suggested; and a List of BRANCHES OF INSTRUCTION OMITTED, with an indication of the Grounds of the omission.

N. B.—The hard words, viz. those derived from the Greek or Latin, are throughout explained. Through necessity alone are they here employed. Under almost every one of these names will be found included objects already familiar in every family; even to children who have but just learnt to read.

ADVANTAGES

derivable from Learning, or Intellectual Instruction: viz.

I. From Learning as such;—in whatsoever particular shape obtained.

1. Securing to the possessor a proportionable share of general respect.

2. Security against ennui, viz. the condition of him who, for want of something in prospect that would afford him pleasure, knows not what to do with himself a malady, to which, on retirement, men of business are particularly exposed. (1.)

3. Security against inordinate sensuality, and its mischievous consequences. (2.)

4. Security against idleness, and consequent mischievousness. (3.)

5. Security for admission into, and agreeable intercourse with, good company: i. e. company in, or from which, present and harmless pleasure, or future profit or security, or both, may be obtained.

II. From Learning, in this or that particular shape, and more especially from the proposed course of Intellectual Instruction.

1. Multitude and extent of the branches of useful skill and knowledge: the possession of which is promised by this system, and at an early age. (4.)

2. Increased chance of lighting upon pursuits and employments most suitable to the powers and inclinations of the youthful mind, in every individual case. (5.)

3. General strength of mind derivable from that multitude and extent of the branches of knowledge included in this course of instruction. (6.)

4. Communication of mental strength considered in its application to the business chosen by each pupil, whatever that business may be. (7.)

5. Giving to the youthful mind habits of order applicable to the most familiar, as well as to the highest purposes: good order, the great source of internal tranquillity, and instrument of good management. See Stage V. (8.)

6. Possession of sources of comfort in various shapes, and security against discomfort in various shapes. See, in particular, Stages III. and IV.

7. Security of life, as well as health: that blessing, without which no such thing as comfort can have place. See Stage IV.

8. Security afforded against groundless terrors, mischievous impostures, and self-delusions. See Stages II. III. and IV. (9.)

9. Securing an unexampled choice of well-informed companions through life. (10.)

10. Affording to parents a more than ordinary relief from the labour, anxiety, and expense of time necessary to personal inspection. (11.)

11. Unexampled cheapness of the instruction, in proportion to its value. (12.)

12. Least generally useful branches last administered; and thence, in case of necessity, omissible with least loss. (13.)

13. Need and practice of corporeal punishment superseded: thence masters preserved from the guilt and reproach of cruelty and injustice. (14.)

14. Affording, to the first race of scholars, a mark of particular distinction and recommendation. (15.)

15. Enlargement given to each scholar’s field of occupation. (16.)

Objections answered.

1. Supposed impracticability. Granting your endeavour to be good, the accomplishment of it will not be possible. (17.)

2. Disregard shown to classical learning, and other polite accomplishments. (18.)

3. Superficiality and confusedness of the conceptions thus obtainable. (19.)

4. Uppishness a probable result of the distinctions thus obtained. (20.)

Relations.

of the proposed, to the existing great schools, universities, and other Didactic institutions. (21.)

Obstacles and Encouragements. (22.)

Adverse Prejudices obviated.

1. Novelty of the plan. (23.)

2. Abstruseness of the subjects. (24.)

General Concluding Observations. (25.)

GROUNDS OF PRIORITY;

Or circumstances, on which, as between one subject of intellectual instruction and another, the order of priority in which they are most advantageously taught, depends.

1. On the part of the mind, the relative degree of preparedness, with relation to the subject and mode of instruction in question.

2. The natural pleasantness (26.) of the subject.

3. The artificial pleasantness (27.) given to the subject, or mode of instruction.

Observations as to relative preparedness.

I. Circumstances on which such preparedness depends.

1. Corporeal ideas find the mind earlier prepared for their reception than incorporeal ones. (28.)

2. Concrete, than abstract ones. (29.)

3. Ideas find the mind the earlier prepared for their reception, 1. the less they have in them of an incorporeal nature, 2. the less extensive, 3. numerous, 4. various, and 5. complex or complicated (30.) they are; and the less they include of what belongs to the relation between cause and effect. (31.)

II. Circumstances, on which such preparedness does not depend.

1. The name, more or less familiar or abstruse, of the art or science (32.) under which the particular subject or object in question has been ranked.

2. The antiquity (33.) of the art or science, i. e. the length of time since the study of it happened to come into use.

3. The number of the persons who, in the respective capacities of learners and teachers (34.) happen to be, at the time in question, occupied in the art or science.

N. B.—Before entrance, the degree of preparedness will, in the instance of each scholar, be ascertained by examination. After entrance, it may, in relation to an indefinite number of branches of instruction, and to an indefinite amount in each, happen to it to receive increase from sources external to the school. But of any such increase (the whole being casual) no account can, to any such purpose as that of modifying the course of the school instruction, be taken. The absence of all such increase is, therefore, the only supposition upon which any arrangement can be built.

INTRODUCTORY, Preparatory, or Elementary STAGE. (35.)

Elementary Arts.

- 1. Reading (taught by writing.)

- 2. Writing.

- 3. Common Arithmetic.

And see Stage I.

Stage I.

Natural History.

- 1. Mineralogy. (36.) } exhibited in the most familiar points of view.

- 2. Botany. (37.)

- 3. Zoology. (38.)

- 4. Geography (39.) (the familiar part.)

- 5. Geometry (40.) (the definitions explained by diagrams or models.)

- 6. Historical Chronology. (41.)

- 7. Biographical Chronology. (42.)

- 8. Appropriate Drawing. (43.)

Stage II.

Natural Philosophy.

- I. Mechanics at large.

- II. Chemistry (50.) at large; including Chemical Pneumatics.

- III. Subjects belonging to Chemistry and Mechanics jointly.

- 11. Magnetism. (55.)

- 12. Electricity. (56.)

- 13. Galvanism. (57.)

- 14. Balistics. (58.)

- 15. Geography continued. (59.)

- 16. Geometry continued. (60.)

- 17. Historical Chronology continued. (61.)

- 18. Biographical Chronology continued.

- 19. Appropriate Drawing continued. (62.)

- 20. Grammatical Exercises, applied to English, Latin, Greek, French, and German, in conjunction. (63.)

Stage III. (64.)

- 1. Mining. (65.)

- 2. Geognosy or Geology. (66.)

- 3. Land-Surveying and Measuring. (67.)

- 4. Architecture. (68.)

- 5. Husbandry (including Theory of Vegetation and Gardening.) (69.)

- 6. Physical Economics, i. e. Mechanics and Chemistry, applied to domestic management and the other common purposes of life. (70.)

- 7. Geography continued.

- 8. Geometry continued.

- 9. History continued.

- 10. Biography continued.

- 11. Appropriate Drawing continued.

- 12. Grammatical Exercises, applied as above, continued.

Stage IV.

Hygiastics, or Hygiantics (71.) the art of preserving, as well as restoring Health, including the arts and sciences thereto belonging viz.

- 1. Physiology. (72.)

- 2. Anatomy. (73.)

- 3. Pathology. (74.)

- 4. Nosology. (75.)

- 5. Diætetics. (76.)

- 6. Materia Medica. (77.)

- 7. Prophylactics. (78.)

- 8. Therapeutics (79.) at large.

- 9. Surgery, i. e. Mechanical Therapeutics. (80.)

- 10. Zohygiantics, i. e. Physiology, &c. applied to the inferior animals. (81.)

- 11. Phthisozoics, the art of destruction, applied to noxious animals. (82.)

- 12. Geography continued.

- 13. Geometry continued.

- 14. History continued.

- 15. Biography continued.

- 16. Appropriate Drawing continued.

- 17. Grammatical Exercises continued.

Stage V.

Mathematics. (83.)

- 1. Geometry (84.) (with demonstrations.)

- 2. Arithmetic (85.) (the higher branches.)

- 3. Algebra (86.)

- 4. Uranological Geography. (87.)

- 5. Uranological Chronology. (88.)

- 6. History continued.

- 7. Biography continued.

- 8. Appropriate Drawing continued.

- 9. Grammatical Exercises continued.

- 10. Technology, or Arts and Manufactures in general. (89.)

- 11. Book-keeping at large; i. e. the art of Registration or Recordation. (90.)

- 12. Commercial Book-keeping. (91.)

- 13. Note-taking (92.) applied to Recapitulatory Lectures, on such of the above branches as admit and require it.

BRANCHES OF INSTRUCTION omitted; viz. on one or more of the ensuing GROUNDS; to wit,

I. School-Room insufficient. (93.)

II. Admission pregnant with exclusion. (94.)

III. Time of life too early. (95.)

IV. Utility not sufficiently general; viz. as being limited to particular ranks or professions. (96.)

☞ In the instance of each branch, indication is given of the ground or grounds of omission, by the numerals prefixed as above.

I. Gymnastic Exercises. (97.)

1. Dancing. i.

2. Riding (the Great Horse.) i. iii.

3. Fencing. i. iii. iv.

4. Military Exercise. (98.) i.

II. Fine Arts.

| 5. | {1. | Music. i. ii. |

| 6. | {2. | Painting. i. iv. |

| 7. | {3. | Sculpture. i. iv. |

| 8. | {4. | Engraving. i. iv. |

III. Applications of Mechanics and Chemistry.

| (99.) [Art of War:] including Tactics, Military and Naval. Of this art, the Military Exercise is itself one branch. So far as concerns this branch, neither can the utility of it (when the female sex is excepted) be said not to be sufficiently general, nor the time of life too early, so far as concerns the last year or two of the proposed schooltime. | ||

| 9. | {1. | Gunnery. i. ii. iv. |

| 10. | {2. | Fortification. i. iv. |

| 11. | {3. | Navigation. i. iv. |

| 12. | {4. | Art of War. i. iii. iv. (99.) |

IV. Belles Lettres.

| 13. | {1. | Literary Composition at large. (iii.) |

| 14. | {2. | Poetical Composition. iii. |

| 15. | {3. | Rhetorical Composition. iii. |

| 16. | {4. | Criticism. iii. |

V. Moral Arts and Sciences.

| (100.) [Private Ethics or Morals.] Important as is this branch of art and science, admission cannot consistently be given to it in the character of a distinct branch of art and science. Controverted points stand excluded, partly by the connexion they are apt to have with controverted points in Divinity, partly by the same considerations by which controverted points in divinity are themselves excluded. Uncontroverted points will come in—come in of course, and without any particular scheme of instruction—on the occasion of such passages in History and Biography, as come to be taken for the subjects of Grammatical and other Exercises. | ||

| 17. | {1. | Divinity. ii. iii. |

| 18. | {2. | Private Ethics or Morals (controverted points.) ii. iii. (100.) |

| 19. | {3. | Law (National.) iii. |

| 20. | {4. | International Law. iii. iv. |

| 21. | {5. | Art and Science of Legislation in general. iii. iv. |

| 22. | {6. | Political Economy. iii. iv. |

VI. All-directing Art and Science.

23. Logic (by some called Metaphysics.) iii.

N. B.—In regard to several of the branches in this list, the proposition by which the omission is prescribed, as likewise the Ground on which it is prescribed, may, in some way or other, be found susceptible of modification. But whatever may, in this or that instance, be thought of the filling up, the scheme of the outline may, it is hoped, be found to have its use.

☞ It is supposed that few, if any, existing branches of Art or Science can be found, which are not included in one or other of the Denominations inserted in this Table. In so far as this is the case, it may, in some measure, serve the purpose of an Encyclopædical sketch.

NOTES TO CHRESTOMATHIC TABLES.

TABLE I.

Advantages derivable from Learning or Intellectual instruction: viz.

I. From learning, as such, in whatsoever particular shape obtained.

Advantage the First: Securing to the possessor a proportionable share of general respect. See Table I.

Advantage Second: Security against ennui, viz., the condition of him who, for want of something in prospect that would afford him pleasure, knows not what to do with himself: a malady to which, in retirement, men of business are particularly exposed.

Objections Answered.

Having considered the advantages promised by the proposed course of Intellectual Instruction, it may be of use now to consider the objections which may be urged against it.

Objection First: Supposed impracticability. Granting your endeavour to be good, the accomplishment of it will not be possible.

Relations

of the proposed to the existing Great Schools, Universities, and other Didactic Institutions.

Obstacles and Encouragements.

Grounds of Priority.

Edition: current; Page: [28]Stages.

Note-taking being, in so far as the note falls short of being a complete copy, a species of composition, and, as such, in some sort, a product of invention, and that product produced extempore, and affording, at the same time, the most correct test of the correctness and completeness of the conception which, as appears by the note thus taken, has been formed of the original discourse: this is the sort of exercise, to the performance of which the maturest state of the mind is requisite; and which, therefore, ought to be the last of all the exercises, performed in relation to the several subjects of instruction that have place in the whole of the aggregate course. When all the several particular courses have been gone through, without the benefit of this auxiliary task, then will be the time for determining which of them stand most in need of it, and thereupon to which of them it shall be afforded.

CHRESTOMATHIC INSTRUCTION TABLES. TABLE II.

Showing, at one view, the PRINCIPLES constitutive of the New-Instruction System, considered as applicable to the several ulterior branches of Art and Science-Learning (Language-Learning included) through the medium of the several sorts of EXERCISES, by the performance of which Intellectual Instruction is obtained or obtainable.

☞ The perfection of the System consisting, in great measure, in the co-operation and mutual subserviency of the several Principles, any adequate conception of its excellence and sufficiency, especially with a view to the here proposed extension, could scarcely (it was thought) be formed, without the benefit of a simultaneous view, such as is here exhibited.

By the figures subjoined to each Principle, reference is made to the Volumes and Pages of Dr Bell’s Elements of Tuition, London, 1814, in which that Principle is mentioned or seems to have been had in view; some of the principal passages are distinguished by brackets. The references to Vol. II. are put first, that being the Volume in which the explanations are given. The articles for which no authority has been found, in Dr Bell or elsewhere, are distinguished by not being in Italics.

INTELLECTUAL EXERCISES:

in the application of which to the purpose of Instruction, School Management consists: viz.

I.: Mathetic (a) Exercises.

1. Applying attention to portions of discourse, orally or scriptitiously (1.) delivered, in such sort as to conceive, remember, and occasionally recollect, and repeat them, in terminis.

2. Or in purport. (2.)

3. Applying attention to sensible (3.) objects, to the end that, by means of correspondent and concomitant portions of discourse, their respective properties may so far be conceived, remembered, and occasionally recollected and repeated: viz. either in the terms, or according to the purport, of such discourse.

4. Performance of organic (4.) exercises, in so far as performed for the simple purpose of attaining proficiency in the performance of those same operations, and not as per No. 9.

II.: Probative (b) Exercises.

§ I. Universally applicable to all branches of Intellectual learning.

5. i. Simply recitative (5., 6.) Exercises, performed in terminis.

6. ii. Simply recitative (5., 6.) Exercises, performed in purport.

7. iii. Responsive (7., 8.) Exercises performed in terminis.

8. iv. Responsive (7., 8.) Exercises performed in purport.

9. v. Performance of organic operations, in so far as employed as tests of intellection (9.) and proficiency, in regard to corresponding Mathetic Exercises.

10. vi. Note-taking: i. e. the extempore taking of Notes, or Memorandums, of the purport of Didactic discourses, while orally delivered; accompanied or not by exhibitions, as above, No. 3.

§ II. Exclusively applicable to Language learning.

11. i. Parsing, Canoniphantic, or Grammaticosyntactic Relation and Rule indicative Exercise.

12. ii. Single Translation Exercise.

13. iii. Double or reciprocating Translation Exercise.

14. iv. Purely syntactic composition Exercise, or Clark’s Exercise.

15. v. Purely syntactic prosodial composition Exercise, or Metre-restoring Exercise.

16. vi. Prosodial non-significant or Purely metrical (original) composition Exercise.

17. vii. Purely metrical Translation Exercise.

PRINCIPLES OF SCHOOL MANAGEMENT: (c)

applicable to Intellectual Instruction, through the medium of those same Exercises: viz.

I.—: To all branches without distinction.

I. Principles, relative to the Official Establishment: i. e. to the quality and functions of the Persons, by whom the performance of the several Exercises is to be directed.

1. Scholar-Teacher employment maximizing principle.

II. xiii. 29. 31. 33. 43. 44. 75. 79. 81. 82. 87. 99. 125. 133. 134. 197. 201. 210. 222. 223. 229. 237. 241. 265. 267. 362. 368. 369. 370. 371. 388. 403. 411. 424. 425. 426. 427. 431. 439.

I. v. xxvi. xxx. 1. 22. 23. 37. 40. 41. 48. 115 to 126.

2. Contiguously proficient Teacher preferring principle. ii. 271.

3. Scholar-tutor employment maximizing, or Lesson-getting Assistant employing, principle. ii. 90. 93. 110. 212. 220. 237. 249. 283. 299. 329. 343. 344. 366. 368. 369. 399. 401.

4. Scholar-Monitor employment maximizing, or Scholar Order-preserver employment maximizing, principle. ii. 90. 213. 403. 439.

5. Master’s time economizing, or Nil per se quod per suos, principle. ii. 263.

6. Regular Visitation, or Constant Superintendency providing, principle. ii. 191. 213. 227. 323. 419. 420. 422. 427. 431. 432. i. 126.

II. Principles, having, for their special object, the preservation of Discipline: i. e. the effectual and universal performance of the several prescribed Exercises, and the exclusion of disorder: i. e. of all practices obstructive of such performance, or productive of mischief in any other shape; and, to that end, the correct and complete observance of all arrangements and regulations, established for either of those purposes.

7. i. Punishment minimizing, and Corporal Punishment excluding principle. ii. 78. 84. 124. 127. 195. 196. 208. 232. 233. 236. 262. 343. 346. 389. 410. 439. i. 39. 43. 89. 90. 123.

8. ii. Reward economizing principle. ii. 262. 346. 347. 348. 349.

9. iii. Constant and universal Inspection promising and securing principle. ii. 237. i. 38.

☞ To this belongs the Panopticon Architecture employing principle.

10. iv. Place-capturing, or Extempore degradation and promotion, principle. ii. 124. 134. 137. 194. [207.] 216. 235. 250. 251. 254. 259. 280. 283. 286. 287. 289. 301. 314. 315. 329. 337. 343. 357. 358. 359. 360. 369. 410. 439. 442.

11. v. Appeal (from Scholar-master) providing principle.

12. vi. Juvenile Penal Jury, or Scholar Jurymen employing principle. ii. 209. 214. 228. 229. 234. [236.] 261. 346. 368. 402. 426. i. 43.

III. Principles, having, for their special object, the securing the forthcomingness of Evidence: viz. in the most correct, complete, durable and easily accessible shape: and thereby the most constant and universal notoriety of all past matters of fact, the knowledge of which can be necessary, or conducive, to the propriety of all subsequent proceedings; whether for securing the due performance of Exercises, as per Col. i. or for the exclusion of disorder, as per Col. ii.

13. i. Aggregate Progress Registration, or Register employing, principle. ii. 214. 228. 229. 251. [257.] [258.] 263. 273. 293. 340. 360. 363. 368. 373. 419. 420. 422. 427. 432. i. 78. 117.

14. ii. Individual and comparative proficiency registration, or Place-competition-result Registration employing, principle. ii. 230. 231. 259. 265. 275. 330. i. 30. 31. 116.

15. iii. Delinquency registration, or Black-Book employing, principle. ii. 214. 231. 232. 234. [235.] 261. 346. 368. 369. i. 43. 89.

16. iv. Universal Delation principle, or Non-Connivance tolerating, principle. ii. 234. 236. 264. 361. 366.

IV. Principles, having, for their special object, the securing perfection: viz. in the performance of every Exercise, and that in the instance of every Scholar, without exception.

17. i. Universal proficiency promising principle. ii. 46. 78. 83. 118. 127. 283. 368. 372. 386. 387. 401. i. 30. 32. 109.

18. ii. Non-conception, or Non-intellection, presuming, principle, ii. 255. 256. 259. 365.

19. iii. Constantly and universally perfect performance exacting, or No-imperfect performance tolerating, principle. ii. 134. 252. 253. 263. 271. 276. 279. 284. 292. 293. 294. 297. 298. 309. 313. 324. 325. 339. 340. 342. 352. 353. 354. 355. 357. 387. 439. 441. 443.

20. iv. Gradual progression securing, or Gradually progressive Exercises employing, principle, ii. 308. 427. 439. 442.

21. v. Frequent and adequate recapitulation exacting principle. See 19. iii.

22. vi. Place-capturing probative exercise employment maximizing principle. See 10. iv.

23. vii. Fixt verbal standard employment, and Verbal conformity exaction, maximizing principle. Lancaster’s Improvements, p. 84. Bell, ii. 440. 441. 443.

24. viii. Organic Intellection-Test employment maximizing principle. ii. 273. 275. 289. 290. i. 25. 26. 37.

25. Note-taking Intellection-Test employment maximizing principle.

26. ix. Self service exaction maximizing principle. ii. 87. 327. 328. i. 28.

27. x. Task-descriptive enunciation and promulgation exacting principle. ii. 287. 290. 354. 363. 373. 442.

28. xi. Constant all-comprehensive and illustrative Tabular Exhibition maximizing principle.

29. xii. Distraction preventing, or Exterior object excluding, principle.

30. xiii. Constantly and universally apposite Scholar-classification securing principle. ii. 82. 124. 127. 132. 209. 212. 215. [216.] 217. 218. [243.] 263. 338. 340. 345. 359. 362. 387. 395. 401. 439. 441. i. 29. 125.

V. Principles, having, for their special object, the union of the maximum of despatch with the maximum of uniformity; thereby proportionably shortening the time, employed in the acquisition of the proposed body of instruction, and increasing the number of Pupils, made to acquire it, by the same Teachers, at the same time.

31. i. Simplification maximizing, or Short lesson employing, principle. ii. 194. 195. 202. 203. [207.] 208. 210. [223.] 224. 263. 265. 272. 275. 294. 302. 331. 351. 355. 356. 362. 363. 369. 371. 385. 410. 427. 441. 442. 439.

32. ii. Universal-simultaneousaction promising and effecting principle. ii. 215. 285. 287.

33. iii. Constantly-uninterrupted-action promising and effecting principle. ii. 252. 263. 283. 364. 439.

34. iv. Word of command employing, or Audible-direction abbreviating principle. (Lancaster, 110. See No. 23.) ii. 250 to 254. 280. 281. 310. 360. 363. i. 30.

35. v. Universally visible signal, or pattern employing, or Universally and simultaneously visible direction employing, principle. ii. 254. 270. 275. 279. 440. 443.

36. vi. Needless repetition and commoration excluding principle. ii. 252. 282. 288. 354. 373. 439. 442.

37. vii. Remembrance assisting Metre-employment maximizing principle.

38. viii. Employment varying, or Task-alternating principle. ii. 252. 283. 289. 290. 264.

II.—: To particular branches exclusively:

I. To the arts of Speaking, Reading, and Writing.

39. i. Constantly distinct intonation exacting principle. ii. 132. 299.

40. ii. Syllable lection exacting, or Syllable-distinguishing intonation employing, principle. ii. 287. 362. 370. 412. i. 27.

41. iii. Recapitulatory-spelling discarding, or Unreiterated-spelling exacting, principle. ii. 280. 303. 304. 306. 370. 412.

42. iv. Vitiously retroactive repetition, or Balbutient recollection-assisting repetition prohibiting, principle, ii. 132. 240. 252. 260. 262. 288. 354. 373.

43. v. Sand-Writing employing, or Psammographic, principle. ii. 88. 89. 91. 270. 274. 276. 279. 327. 350. 370. 412. 427. 441. i. 24. 25.

II.To Geometry and Algebra.

☞ For several proposed principles of instruction not referable to this system, see the tract, printed as Appendix, No. VIII.

NOTES TO TABLE II.

I.—: NOTES TO THE EXERCISES.

(10.) [Note-taking.] The principal and most immediate use of this exercise is to serve as a test of intellection, as per (No. 9.); especially in so far as the nature of the subject admits not the application of the sort of organic test therein described.

But in it is included a certain species of composition, and thereby a certain degree of invention. It is, therefore, among the highest species of exercise; a task, for the due and effectual performance of which, the maturest state of the minds, for which the course of instruction here in question is designed, will probably be found requisite. Correspondent didactic operations, Prescription and direction of this same exercise, and inspection of the notes, which are the result of it. To one or other of these exercises, mathetic and probative, or both in one, every possible mode of instruction, applicable to intellectual instruction in general, will, it is supposed, be found reducible; and if it be true, as supposed, that there is not one of them which is not—and that with the full benefit of the Bell Instruction System—applicable to all the several branches of that learning, enumerated in the course of this work, the applicability of that system, with a degree of advantage equal to what has been so universally experienced in the lower order of schools, to those several branches, when taught in the proposed Chrestomathic School, will, it is hoped, be found to be placed out of the reach of doubt.

(11.) [Parsing.] In the exercise called parsing, two distinguishable operations are supposed to be commonly included: viz. 1. Indication of the grammatical relations, which the component words of each sentence bear to another; 2. Indication of the grammatical rules, by which the custom of the language, in those particulars, is expressed, and conformity to that custom accordingly prescribed.

[Canoniphantic.] From a Greek word signifying a rule, and another signifying indication. Correspondent didactic operation, Prescription and direction of this same exercise, and, if performed in writing, inspection of the result. This same description applies to the several didactic operations, corresponding to the several exercises herein aftermentioned.

(12.) [Single Translation.] This exercise wears a different character, and is productive of different effects, according as the vernacular language is or is not one of the two languages; and if yes, according as the foreign language in question is translated from, or translated into.

(13.) [Double or reciprocal Translation.] This exercise wears a different character according to the diversifications mentioned in the case of single translation, and according as literal conformity on the one or the other side, or on both, is, or is not, exacted.

(14.) [Clark’s Exercise.] Advantages attached to this exercise, in comparison with translation into, or composition in, the foreign language, with the help of a dictionary. 1. Saving of the time, necessary to the finding out of the word. 2. Saving of the time, naturally and frequently consumed, in inaction or irrelevant reading, in the course of the search. 3. Saving of the perplexity, attendant on the choice between the several words presented by the dictionary; a choice to which, for a long time, the pupil continues irremediably incompetent.

(15.) [Metre restoring.] A verse being chosen by the Master, and the words thrown out of their order, in such sort that they no longer constitute a verse, this exercise consists in restoring them to their order: to which purpose some acquaintance with the nature of the sort of verse, and the rules of Prosody, Edition: current; Page: [46] i. e. versification, in general, is necessary. This exercise operates therefore as a test—not only of remembrance—but of intellection, with regard to those rules.

(16.) [Prosodial non-significant.] In schools this is called making nonsense verses. Accident will every now and then give to the nonsense the appearance of ludicrous sense. To this exercise, the metre restoring exercise may serve as an introduction. It affords a certainty of success: and saves the time, that would otherwise be to be employed in the search of words. By the shortness of the time requisite, it would be, in a particular degree, well adapted to the present system. See No. (31.) Short-Lesson principle. Whether it has anywhere been employed cannot here be stated. The idea of it was suggested by that of Clark’s Exercise.

(17.) [Purely-metrical Translation.] In this case the translation is into metre, and may be performed from other metre, or from prose: the exercise being purely metrical, the language is the same on both sides. One of the Westminster School exercises used to be—taking an epigram of Martial, or an ode of Horace, and translating it into some other of the species of verse to be found in the same books. Its objects are—1. familiarizing the learner with the metre into which he translates; 2. giving him a command of words in the language.

II.: NOTES TO THE PRINCIPLES.

(1.) [Scholar-Teacher Principle.] The principle, which consists in employing, as teachers to the rest, some of the most advanced, and in other respects most capable, among the scholars themselves:—maximizing the use and application made of this principle, i. e. giving to it the utmost extent capable of being given to it with advantage—raising it to a maximum. In this maximization consists the only peculiarity, and correspondent utility, of this part of the system.—Advantages gained, I. Saving in money. Every professional teacher would need to be paid; no such scholar-teacher needs to be, or is paid. II. Saving in Time. Under the inspection of one professional General Master, the whole number of Scholars may be cast into as many classes as there are different branches of instruction, and different degrees of proficiency in each: each such class under the direction of its Scholar-Teacher; the instruction of all these classes going on at the same time. III. Increase in relative optitude. 1. For securing the attention of a grown person in the character of Teacher to such business, especially in the case of those lowest branches, which form the occupation of children but just emerged from infancy, the nature of the case scarce admits of any other generally applying motive than fear; viz. the fear of losing the situation; i. e. the provision annexed to it. In it he can find neither instruction, amusement, nor, except that fear, any other cause of interest: his attention is perpetually called off by such other ideas, whatsoever they may be, in which, for the moment, it happens to him to take an interest. In the breast of the Scholar-Teacher, the honour and power, attached to the function, cannot fail of operating in the character of a reward; of a reward, the operativeness and sufficiency of which has been proved by an ample and uninterrupted body of experience. Instead of being so completely stale as in the other case, the subject, contemplated in this new point of view, is not yet become so familiar as to have lost altogether the sort of interest, which, particularly in a juvenile mind, is attached to novelty:—especially, coupled as it is with the situation of judge, presiding on the occasion of the contest, produced by the application of the place-capturing principle, No. (10.) 2. By his age and situation, the juvenile, and completely subject Teacher, is, to a certainty and constancy, rendered more tractable, than a grown-up under-Master can ever be reasonably expected to be. On each point, the grown-up Teacher is liable to have an opinion of his own, and with it a will of his own, contrary to that of his superior and employer; to which will, at any rate during the absence or inattention of such his principal, it is in his power to give effect. To the juvenile and subject Scholar-Teacher, this can never happen. The Edition: current; Page: [47] professional under-Teacher, be his negligence or perversity what it may, cannot be subjected to any other punishment than that of dismissal: a punishment, by the infliction of which, it will frequently happen, that the judge would be no less a sufferer than the delinquent. IV. By teaching others, the scholar is, at the same time, teaching himself: imprinting, more and more deeply, into his own mind, whatsoever ideas he has received into it in the character of a learner: taking of them, at the same time, a somewhat new and more commanding view, tinged, as they are, with an enlivening colour by the associated ideas of reputation, and of that power, which has been the fruit of it.

The application of this principle is, therefore, not a make-shift, occasionally employed, as under the old system, for want of a sufficient supply of grown-up under-Teachers, but an essential feature, operating to the complete and purposed exclusion, of all such naturally reluctant and untractable subordinates.

But the faculty, of giving to this principle any such extension to advantage, depends, in no inconsiderable degree, on several other parts of the system, viz. on the simplicity, and thence on the shortness, of the lessons, as per No. (31.); on the extent to which the practices of repetition and responsion in terminis, Exercises, No. (5.) and (7.) can be applied to advantage, and thereupon to the extent to which, in the character of a test of intellection, as per No. (24.) and (25.), their checks, viz. the organic species of exercise, and the note-taking exercise, can be employed; and in so far as responsion in purport is either extracted or received, the allowance given to eventual appeal, as per No. (11.), from the decisions of the juvenile under-Teacher to the Master—the supreme and universal judge.

(2.) [Contiguous proficiency principle.] On this sort of contiguity depends, as hath just been seen, no small part of the advantage, which the case of the Scholar-Teacher has over that of the grown-up Teacher: but, the higher advanced in the line of proficiency the Scholar-Teacher is above his pupils, the nearer does his situation approach to that of grown-up Teacher: honour less, power less gratifying, instruction and amusement, if any, less and less. At the same time, what may not unfrequently happen, especially in the case of the lowest classes, is, that at an age, at which, in respect of proficiency in learning, he is ripe for the office, the Scholar is not so as yet in respect of the faculty of discretion, or that of judicature. So far as, in respect of these latter qualifications, a deficiency has place, so far a departure from the contiguous proficiency principle may be found necessary.

(3.) [Scholar-Tutor principle.] The Scholar-Teacher delivers the directions to the whole number of pupils in a class at once; he presides over the probative, and in particular over the recitative and responsive exercises, Nos. (5.) and (7.), performed by all together, under the spur of the place-capturing principle, No. (10.)—exercises, by the performance of which the several lessons are said. By the Scholar-Tutor, assistance is, in case of need, afforded to some one other Scholar, attached to him for this purpose in the character of a private pupil, during the several portions of time, allotted for the getting of the respective lessons. The local station of the Scholar-Teacher is, consequently, a distinguished and solitary one; that of the Scholar-Tutor is a social one, just by the side of his pupil. The less the degree of general capacity on the part of the pupil, the greater is the degree of the like capacity needful on the part of the occasional assistant. On this principle it is, that the operation of pairing is performed. Suppose, in one class, eleven Scholars, and to each a different degree of capacity, for this purpose, ascribed; he who has eleven degrees is paired with him who has but one; he who has ten degrees, with him who has two; he who has six degrees, remaining single.

(4.) [Scholar-Monitor principle.] Of this office—an office of indispensable necessity in all large schools upon the ordinary plan—little or no need will probably be found, on the plan of architectural construction prescribed by the Panopticon principle, No. (9.), by which every human object in the whole building is kept throughout within the reach of the Head-Master’s eye.

[Master’s Time-saving principle.] The Managing Master is but one: to the number of the Scholar-Masters there are no limits, but what experienced convenience dictates. Whatsoever can be equally well done by any one or more of them, his time would be very ill employed in doing or endeavouring to do. General inspection and direction is the business which must be done by him, and cannot be done by any one else: whatsoever time is by him employed on any other business, the danger is, lest it be taken from that which is necessary to the performance of his peculiar business, as above.

(6.) [Regular Visitation principle.] The operation of this sort of tribunal is an advantage which a school, instituted and supported by contributions, possesses in comparison with an ordinary school. By the schools carried on under the superintendence of the Society called the National Society, it may in general be expected to be possessed, in a degree more or less considerable, according to local circumstances. By the Chrestomathic School, it may reasonably be expected to be possessed in a still superior degree, the superiority of which will be proportioned to the ulterior interest possessed by the conductors in this case, in addition to that possessed by the superintendants in that other case. But the means which the visiters, be they who they may, have for the execution of their trust to advantage and with effect, depend almost altogether upon the principles, Nos. (13, 14, 15, 16,) respecting Edition: current; Page: [48] Evidence: the good effects producible by the judgment which, on each occasion, they pronounce, and the arrangements which they make in relation to what is to be done, are completely dependent upon the knowledge which they possess, upon the information which they have received, concerning what has been done.

(7.) [Punishment minimizing principle.]

(8.) [Reward economizing principle.] Two intimately connected principles, both of them of cardinal importance, may be seen, in the idea and practice of setting up these results in the character of ends or objects to be aimed at: these, together with the several maximizing principles, Nos. (1.) (3.) (13.) (14.) (22.) (23.) (24.) (25.) (26.) (31.) (37.) and the several promissory principles, Nos. (17.) (19.) (30.) (32.) (33.) may be considered as so many branches of that all-pervading principle, so peculiar to this system, by which perfection, on every point, the idea of it having been conceived, is represented as capable of being, and therefore as being what ought to be, obtained. To give effect to these two principles is the object and effect of the four others which, in this same division, follow them.

Facility of delinquency, inapplicability of reward, uncertainty of the forthcomingness of evidence, and thence of the application of whatever of punishment or reward may be intended to be administered,—as those several quantities increase, so does the quantity (i. e. the intensity or duration) of the punishment, necessitated: in proportion as any of these quantities decrease, so (if nothing be wrong in the system of judicature) may the quantity of punishment denounced and applied: always understood, that punishment is no punishment unless, supposing it inflicted, the suffering produced by it is, in the eyes of the person under temptation, greater, than the enjoyment expected from the offence. By the application made of the Inspection principle, No. (9.) and the Scholar-Tutor principle, No. (3.), the facility of delinquency is, in all its shapes nearly done away: by the Short Lesson principle, No. (31.) the pain of labour, and thence the pleasure afforded by delinquency in the shape of idleness, is minimized; by the Place-capturing principle, No. (10.), reward to the well-doer is rendered, so far, a constant accompaniment of the gentle punishment, brought on the offender by the offence: by the principles respecting evidence, Nos. (13.) (14.) (15.) (16.), operating in conjunction with the Inspection principle, all uncertainty respecting evidence is done away.

As to reward but for the apparent paradoxicality and anti-sentimentality, instead of economizing, minimizing would, in this case, as in the case of punishment, have been inserted. For (perfectly free donations excepted) never can the matter of reward be obtained, to pour into one bosom, but at the expense of suffering, however remote and disguised, inflicted upon others. Neither in power, in dignities, in honours—no, nor even in simple reputation, will any exception be found to this rule. Therefore it is, that, in a government, though tyranny may exist without profusion, profusion cannot exist without correspondent tyranny.

(9.) [Inspection principle.] In the Bell-Instruction System in general, in virtue of the Scholar-Teacher, &c., principles Nos. (1.) (3.) (4.), and the Master’s time saving principle, No. (5.), with or without locomotion on the part of the Master, this object, it may be reasonably supposed, is nearly accomplished: though, in so far as concerns inspection by the Master, the degree will naturally be less and less, in proportion as the School-room is more ample, and by that means drawn out into length. By the Panopticon principle of construction, security, in this respect, is maximized, and rendered entire: viz., partly by minimizing the distance between the situation of the remotest Scholar and that of the Master’s eye; partly, by giving to the floor or floors that inclination, which, to a certain degree, prevents remoter objects from being eclipsed by nearer ones; partly by enabling the Master to see without being seen, whereby, to those who, at the moment, are unseen by him, it cannot be known that they are in this case. In the Chrestomathic School this plan of construction is of course to be employed.

(10.) [Place-capturing principle.] On the occasion of the saying of a lesson, whatever it be, the scholars, by whom that same lesson has been got, are placed, or are kept. standing or sitting, in one line, straight or curved, as is found most convenient; with an understanding, that he whose place is at one end of the line is considered (no matter on what account) as occupying, at the time, the post of greatest honour; the one whose place is next to his, the post next in honour; and so on. The highest scholar, as above, begins to say the lesson: in case of an error, the next highest, on giving indication of it, takes, in pursuance of an instantaneous adjudication, the first place, which the sayer of the lesson is, in punishment for such his delinquency, adjudged to lose: failing the next, the next but one; and so on to the lowest. By this means, the intellectual exercise, be it what it may, is, like most of those corporal exercises in which youth are wont to occupy themselves for mere amusement, converted into a game: punishment attaching instantaneously upon demerit, and, by the same operation, reward upon merit, and in both cases, without further trouble or expense in any shape.

(11.) [Appeal providing principle.] viz. from Scholar-master in any one of these his three characters, Public-teacher, Private-tutor, and Monitor. For this appeal, the principal, and, indeed, almost sole demand, will be found to be that which is capable of being constituted by the application of the Place-capturing principle, No. (10): especially where, on the occasion of the probative exercise to which it Edition: current; Page: [49] is applied, either no fixt verbal standard of reference, as per No. (23.) is employed, or where, this sort of standard being employed, literal conformity to it is not exacted. The greater the latitude allowed to performance, the greater the room for error, and suspicion of error, in whatsoever Judgment may happen to have been passed upon it.

(12.) [Scholar Jury principle.] Advantages. 1. The Master stands hereby preserved, in a great degree, if not altogether, from the suspicion of partiality and tyranny. 2. By the necessary solemnities by which the application of the punishment is thus preceded, the attention of the scholar is more firmly fixt upon it, and the idea of it rendered the more impressive. 3. The scholars are, at this early age, initiated in the exercise of the functions of judicature, as well as in the knowledge of what belongs to justice, while the love of it instils itself into their breasts. 4. The tendency, so natural amongst persons of any age subject to coercion, to unite in a sort of standing conspiracy against those by whom they are kept under that pressure, is counteracted and diminished.

(13.) [Progress Registration principle.]

(14.) [Comparative Proficiency principle.] Every lesson being taken from some determinate book, the designation of every exercise is performed and perpetuated by reference made to that part of the book which has been the subject of it. On each day, of the lessons which, on that day, have, by the several classes, been got and said, together with the organic exercises, No. (24.), if any, which have been performed, the designation is given, by entries made in the Aggregate Register; and, at the same time, the name of each scholar, present or absent, belonging to each class, together with the rank which, as the result of the place-capturing contest, No. (10.) of that day, or the last on which he was present, has remained to him in his class. The Comparative proficiency Register contains a distinct head for each scholar. It exhibits, for any portion of time, the class he has belonged to, and thence, as above, the lessons, which in that class he has got and said, and the organic exercises which he has performed, and the rank which, putting all the days together, he has occupied in such his class. Thus his account is formed, by copying from the Aggregate Register, and summing up, the numbers expressive of the rank, which he has been found occupying on the several days included in the term: the less the sum, the higher, of course, his rank, taking the whole of the term together. If, for a certain length of time, he is at or near the top of the class, it will be a sign, that he is quite or nearly ripe for removal to a higher class; and, in the meantime, that he is, to a certain degree, qualified for lending assistance, upon occasion, in the character of Prirate Tutor, as per No. (3.) to a class-fellow, whose degree of proficiency, as indicated by the same document, is, in a correspondent degree, inferior to his own; and, in like manner, in proportion as the sum is large, the correspondent and opposite indication is afforded. Thus it is, that this Register forms the basis of the application made of the Scholar-Tutor principle, No. (3.) as well as of the apposite-classification principle, No. (30.)

(15.) [Delinquency Registration principle.]