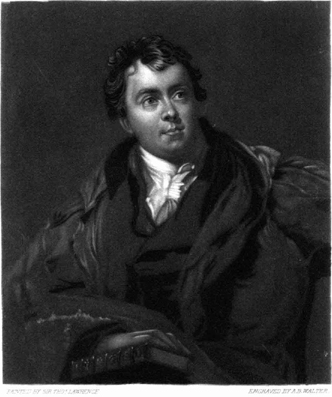

THE MISCELLANEOUS WORKS OF THE RIGHT HONOURABLE SIR JAMES MACKINTOSH

ON THE PHILOSOPHICAL GENIUS OF LORD BACON AND MR. LOCKE.

“History,” says Lord Bacon, “is Natural, Civil or Ecclesiastical, or Literary; whereof of the three first I allow as extant, the fourth I note as deficient. For no man hath propounded to himself the general state of learning, to be described and represented from age to age, as many have done the works of Nature, and the State civil and ecclesiastical; without which the history of the world seemeth to me to be as the statue of Polyphemus with his eye out; that part being wanting which doth most show the spirit and life of the person. And yet I am not ignorant, that in divers particular sciences, as of the jurisconsults, the mathematicians, the rhetoricians, the philosophers, there are set down some small memorials of the schools,—of authors of books; so likewise some barren relations touching the invention of arts or usages. But a just story of learning, containing the antiquities and originals of knowledges, and their sects, their inventions, their traditions, their divers administrations and managings, their oppositions, decays, depressions, oblivions, removes, with the causes and occasions of them, and all other events concerning learning throughout the ages of the world, I may truly affirm to be wanting. The use and end of which work I do not so much design for curiosity, or satisfaction of those who are lovers of learning, but chiefly for a more serious and grave purpose, which is this, in few words, ‘that it will make learned men wise in the use and administration of learning.’ ”

Though there are passages in the writings of Lord Bacon more splendid than the above, few, probably, better display the union of all the qualities which characterized his philosophical genius. He has in general inspired a fervour of admiration which vents itself in indiscriminate praise, and is very adverse to a calm examination of the character of his understanding, which was very peculiar, and on that account described with more than ordinary imperfection, by that unfortunately vague and weak part of language which attempts to distinguish the varieties of mental superiority. To this cause it may be ascribed, that perhaps no great man has been either more ignorantly censured, or more uninstructively commended. It is easy to describe his transcendent merit in general terms of commendation; for some of his great qualities lie on the surface of his writings. But that in which he most excelled all other men, was the range and compass of his intellectual view and the power of contemplating many and distant objects together without indistinctness or confusion, which he himself has called the “discursive” or “comprehensive” understanding. This wide ranging intellect was illuminated by the brightest Fancy that ever contented itself with the office of only ministering to Reason: and from this singular relation of the two grand faculties of man, it has resulted, that his philosophy, though illustrated still more than adorned by the utmost splendour of imagery, continues still subject to the undivided supremacy of Intellect. In the midst of all the prodigality of an imagination which, had it been independent, would have been poetical, his opinions remained severely rational.

It is not so easy to conceive, or at least to describe, other equally essential elements of his greatness, and conditions of his success. His is probably a single instance of a mind which, in philosophizing, always reaches the point of elevation whence the whole prospect is commanded, without ever rising to such a distance as to lose a distinct perception of every part of it. It is perhaps not less singular, Edition: current; Page: [18] that his philosophy should be founded at once on disregard for the authority of men, and on reverence for the boundaries prescribed by Nature to human inquiry; that he who thought so little of what man had done, hoped so highly of what he could do; that so daring an innovator in science should be so wholly exempt from the love of singularity or paradox; and that the same man who renounced imaginary provinces in the empire of science, and withdrew its landmarks within the limits of experience, should also exhort posterity to push their conquests to its utmost verge, with a boldness which will be fully justified only by the discoveries of ages from which we are yet far distant.

No man ever united a more poetical style to a less poetical philosophy. One great end of his discipline is to prevent mysticism and fanaticism from obstructing the pursuit of truth. With a less brilliant fancy, he would have had a mind less qualified for philosophical inquiry. His fancy gave him that power of illustrative metaphor, by which he seemed to have invented again the part of language which respects philosophy; and it rendered new truths more distinctly visible even to his own eye, in their bright clothing of imagery. Without it, he must, like others, have been driven to the fabrication of uncouth technical terms, which repel the mind, either by vulgarity or pedantry, instead of gently leading it to novelties in science, through agreeable analogies with objects already familiar. A considerable portion doubtless of the courage with which he undertook the reformation of philosophy, was caught from the general spirit of his extraordinary age, when the mind of Europe was yet agitated by the joy and pride of emancipation from long bondage. The beautiful mythology, and the poetical history of the ancient world,—not yet become trivial or pedantic,—appeared before his eyes in all their freshness and lustre. To the general reader they were then a discovery as recent as the world disclosed by Columbus. The ancient literature, on which his imagination looked back for illustration, had then as much the charm of novelty as that rising philosophy through which his reason dared to look onward to some of the last periods in its unceasing and resistless course.

In order to form a just estimate of this wonderful person, it is essential to fix steadily in our minds, what he was not,—what he did not do,—and what he professed neither to be, nor to do. He was not what is called a metaphysician: his plans for the improvement of science were not inferred by abstract reasoning from any of those primary principles to which the philosophers of Greece struggled to fasten their systems. Hence he has been treated as empirical and superficial by those who take to themselves the exclusive name of profound speculators. He was not, on the other hand, a mathematician, an astronomer, a physiologist, a chemist. He was not eminently conversant with the particular truths of any of those sciences which existed in his time. For this reason, he was underrated even by men themselves of the highest merit, and by some who had acquired the most just reputation, by adding new facts to the stock of certain knowledge. It is not therefore very surprising to find, that Harvey, “though the friend as well as physician of Bacon, though he esteemed him much for his wit and style, would not allow him to be a great philosopher;” but said to Aubrey, “He writes philosophy like a Lord Chancellor,”—“in derision,”—as the honest biographer thinks fit expressly to add. On the same ground, though in a manner not so agreeable to the nature of his own claims on reputation, Mr. Hume has decided, that Bacon was not so great a man as Galileo, because he was not so great an astronomer. The same sort of injustice to his memory has been more often committed than avowed, by professors of the exact and the experimental sciences, who are accustomed to regard, as the sole test of service to Knowledge, a palpable addition to her store. It is very true that he made no discoveries: but his life was employed in teaching the method by which discoveries are made. This distinction was early observed by that ingenious poet and amiable man, on whom we, by our unmerited neglect, have taken too severe a revenge, for the exaggerated praises bestowed on him by our ancestors:—

- “Bacon, like Moses, led us forth at last,

- The barren wilderness he past,

- Did on the very border stand

- Of the blest promised land;

- And from the mountain top of his exalted wit

- Saw it himself, and showed us it.”

The writings of Bacon do not even abound with remarks so capable of being separated from the mass of previous knowledge and reflection, that they can be called new. This at least is very far from their greatest distinction: and where such remarks occur, they are presented more often as examples of his general method, than as important on their own separate account. In physics, which presented the principal field for discovery, and which owe all that they are, or can be, to his method and spirit, the experiments and observations which he either made or registered, form the least valuable part of his writings, and have furnished some cultivators of that science with an opportunity for an ungrateful triumph over his mistakes. The scattered remarks, on the other hand, of a moral nature, where absolute novelty is precluded by the nature of the subject, manifest most strongly both the superior force and the original bent of his understanding. We more properly contrast than compare the experiments in the Natural History, with the moral and political observations which enrich the Advancement of Learning, the speeches, the letters, the History of Henry VII., and, above all, the Essays, a book which, though it has been praised with equal Edition: current; Page: [19] fervour by Voltaire, Johnson and Burke, has never been characterized with such exact justice and such exquisite felicity of expression, as in the discourse of Mr. Stewart. It will serve still more distinctly to mark the natural tendency of his mind, to observe that his moral and political reflections relate to these practical subjects, considered in their most practical point of view; and that he has seldom or never attempted to reduce to theory the infinite particulars of that “civil knowledge,” which, as he himself tells us, is, “of all others, most immersed in matter, and hardliest reduced to axiom.”

His mind, indeed, was formed and exercised in the affairs of the world: his genius was eminently civil. His understanding was peculiarly fitted for questions of legislation and of policy; though his character was not an instrument well qualified to execute the dictates of his reason. The same civil wisdom which distinguishes his judgments on human affairs, may also be traced through his reformation of philosophy. It is a practical judgment applied to science. What he effected was reform in the maxims of state,—a reform which had always before been unsuccessfully pursued in the republic of letters. It is not derived from metaphysical reasoning, nor from scientific detail, but from a species of intellectual prudence, which, on the practical ground of failure and disappointment in the prevalent modes of pursuing knowledge, builds the necessity of alteration, and inculcates the advantage of administering the sciences on other principles. It is an error to represent him either as imputing fallacy to the syllogistic method, or as professing his principle of induction to be a discovery. The rules and forms of argument will always form an important part of the art of logic; and the method of induction, which is the art of discovery, was so far from being unknown to Aristotle, that it was often faithfully pursued by that great observer. What Bacon aimed at, he accomplished; which was, not to discover new principles, but to excite a new spirit, and to render observation and experiment the predominant characteristics of philosophy. It is for this reason that Bacon could not have been the author of a system or the founder of a sect. He did not deliver opinions; he taught modes of philosophizing. His early immersion in civil affairs fitted him for this species of scientific reformation. His political course, though in itself unhappy, probably conduced to the success, and certainly influenced the character, of the contemplative part of his life. Had it not been for his active habits, it is likely that the pedantry and quaintness of his age would have still more deeply corrupted his significant and majestic style. The force of the illustrations which he takes from his experience of ordinary life, is often as remarkable as the beauty of those which he so happily borrows from his study of antiquity. But if we have caught the leading principle of his intellectual character, we must attribute effects still deeper and more extensive, to his familiarity with the active world. It guarded him against vain subtlety, and against all speculation that was either visionary or fruitless. It preserved him from the reigning prejudices of contemplative men, and from undue preference to particular parts of knowledge. If he had been exclusively bred in the cloister or the schools, he might not have had courage enough to reform their abuses. It seems necessary that he should have been so placed as to look on science in the free spirit of an intelligent spectator. Without the pride of professors, or the bigotry of their followers, he surveyed from the world the studies which reigned in the schools; and, trying them by their fruits, he saw that they were barren, and therefore pronounced that they were unsound. He himself seems, indeed, to have indicated as clearly as modesty would allow, in a case that concerned himself, and where he departed from an universal and almost natural sentiment, that he regarded scholastic seclusion, then more unsocial and rigorous than it now can be, as a hindrance in the pursuit of knowledge. In one of the noblest passages of his writings, the conclusion “of the Interpretation of Nature,” he tells us, “That there is no composition of estate or society, nor order or quality of persons, which have not some point of contrariety towards true knowledge; that monarchies incline wits to profit and pleasure; commonwealths to glory and vanity; universities to sophistry and affectation; cloisters to fables and unprofitable subtlety; study at large to variety; and that it is hard to say whether mixture of contemplations with an active life, or retiring wholly to contemplations, do disable or hinder the mind more.”

But, though he was thus free from the prejudices of a science, a school or a sect, other prejudices of a lower nature, and belonging only to the inferior class of those who conduct civil affairs, have been ascribed to him by encomiasts as well as by opponents. He has been said to consider the great end of science to be the increase of the outward accommodations and enjoyments of human life: we cannot see any foundation for this charge. In labouring, indeed, to correct the direction of study, and to withdraw it from these unprofitable subtleties, it was necessary Edition: current; Page: [20] to attract it powerfully towards outward acts and works. He no doubt duly valued “the dignity of this end, the endowment of man’s life with new commodities;” and he strikingly observes, that the most poetical people of the world had admitted the inventors of the useful and manual arts among the highest beings in their beautiful mythology. Had he lived to the age of Watt and Davy, he would not have been of the vulgar and contracted mind of those who cease to admire grand exertions of intellect, because they are useful to mankind: but he would certainly have considered their great works rather as tests of the progress of knowledge than as parts of its highest end. His important questions to the doctors of his time were:—“Is truth ever barren? Are we the richer by one poor invention, by reason of all the learning that hath been these many hundred years?” His judgment, we may also hear from himself:—“Francis Bacon thought in this manner. The knowledge whereof the world is now possessed, especially that of nature, extendeth not to magnitude and certainty of works.” He found knowledge barren; he left it fertile. He did not underrate the utility of particular inventions; but it is evident that he valued them most, as being themselves among the highest exertions of superior intellect,—as being monuments of the progress of knowledge,—as being the bands of that alliance between action and speculation, wherefrom spring an appeal to experience and utility, checking the proneness of the philosopher to extreme refinements; while teaching men to revere, and exciting them to pursue science by these splendid proofs of its beneficial power. Had he seen the change in this respect, which, produced chiefly in his own country by the spirit of his philosophy, has made some degree of science almost necessary to the subsistence and fortune of large bodies of men, he would assuredly have regarded it as an additional security for the future growth of the human understanding. He taught, as he tells us, the means, not of the “amplification of the power of one man over his country, nor of the amplification of the power of that country over other nations; but the amplification of the power and kingdom of mankind over the world,”—“a restitution of man to the sovereignty of nature,”—“and the enlarging the bounds of human empire to the effecting all things possible.”—From the enlargement of reason, he did not separate the growth of virtue, for he thought that “truth and goodness were one, differing but as the seal and the print; for truth prints goodness.”

As civil history teaches statesmen to profit by the faults of their predecessors, he proposes that the history of philosophy should teach, by example, “learned men to become wise in the administration of learning.” Early immersed in civil affairs, and deeply imbued with their spirit, his mind in this place contemplates science only through the analogy of government, and considers principles of philosophizing as the easiest maxims of policy for the guidance of reason. It seems also, that in describing the objects of a history of philosophy, and the utility to be derived from it, he discloses the principle of his own exertions in behalf of knowledge;—whereby a reform in its method and maxims, justified by the experience of their injurious effects, is conducted with a judgment analogous to that civil prudence which guides a wise lawgiver. If (as may not improperly be concluded from this passage) the reformation of science was suggested to Lord Bacon, by a review of the history of philosophy, it must be owned, that his outline of that history has a very important relation to the general character of his philosophical genius. The smallest circumstances attendant on that outline serve to illustrate the powers and habits of thought which distinguished its author. It is an example of his faculty of anticipating,—not insulated facts or single discoveries,—but (what from its complexity and refinement seem much more to defy the power of prophecy) the tendencies of study, and the modes of thinking, which were to prevail in distant generations, that the parts which he had chosen to unfold or enforce in the Latin versions, are those which a thinker of the present age would deem both most excellent and most arduous in a history of philosophy;—“the causes of literary revolutions; the study of contemporary writers, not merely as the most authentic sources of information, but as enabling the historian to preserve in his own description the peculiar colour of every age, and to recall its literary genius from the dead.” This outline has the uncommon distinction of being at once original and complete. In this province, Bacon had no forerunner; and the most successful follower will be he, who most faithfully observes his precepts.

Here, as in every province of knowledge, he concludes his review of the performances and prospects of the human understanding, by considering their subservience to the grand purpose of improving the condition, the faculties, and the nature of man, without which indeed science would be no more than a beautiful ornament, and literature would rank no higher than a liberal amusement. Yet it must be acknowledged, that he rather perceived than felt the connexion of Truth and Good. Whether he lived too early to have sufficient experience of the moral benefit of civilization, or his mind had early acquired too exclusive an interest in science, to look frequently beyond its advancement; or whether the infirmities and calamities of his life had blighted his feelings, and turned away his eyes from the active world;—to whatever cause we may ascribe the defect, certain it is, that his works want one excellence Edition: current; Page: [21] of the highest kind, which they would have possessed if he had habitually represented the advancement of knowledge as the most effectual means of realizing the hopes of Benevolence for the human race.

The character of Mr. Locke’s writings cannot be well understood, without considering the circumstances of the writer. Educated among the English Dissenters, during the short period of their political ascendency, he early imbibed the deep piety and ardent spirit of liberty which actuated that body of men; and he probably imbibed also, in their schools, the disposition to metaphysical inquiries which has every where accompanied the Calvinistic theology. Sects, founded on the right of private judgment, naturally tend to purify themselves from intolerance, and in time learn to respect, in others, the freedom of thought, to the exercise of which they owe their own existence. By the Independent divines who were his instructors, our philosopher was taught those principles of religious liberty which they were the first to disclose to the world. When free inquiry led him to milder dogmas, he retained the severe morality which was their honourable singularity, and which continues to distinguish their successors in those communities which have abandoned their rigorous opinions. His professional pursuits afterwards engaged him in the study of the physical sciences, at the moment when the spirit of experiment and observation was in its youthful fervour, and when a repugnance to scholastic subtleties was the ruling passion of the scientific world. At a more mature age, he was admitted into the society of great wits and ambitious politicians. During the remainder of his life, he was often a man of business, and always a man of the world, without much undisturbed leisure, and probably with that abated relish for merely abstract speculation, which is the inevitable result of converse with society and experience in affairs. But his political connexions agreeing with his early bias, made him a zealous advocate of liberty in opinion and in government; and he gradually limited his zeal and activity to the illustration of such general principles as are the guardians of these great interests of human society.

Almost all his writings (even his Essay itself) were occasional, and intended directly to counteract the enemies of reason and freedom in his own age. The first Letter on Toleration, the most original perhaps of his works, was composed in Holland, in a retirement where he was forced to conceal himself from the tyranny which pursued him into a foreign land; and it was published in England, in the year of the Revolution, to vindicate the Toleration Act, of which he lamented the imperfection.

His Treatise on Government is composed of three parts, of different character, and very unequal merit. The confutation of Sir Robert Filmer, with which it opens, has long lost all interest, and is now to be considered as an instance of the hard fate of a philosopher who is compelled to engage in a conflict with those ignoble antagonists who acquire a momentary importance by the defence of pernicious falsehoods. The same slavish absurdities have indeed been at various times revived: but they never have assumed, and probably never will again assume, the form in which they were exhibited by Filmer. Mr. Locke’s general principles of government were adopted by him, probably without much examination, as the doctrine which had for ages prevailed in the schools of Europe, and which afforded an obvious and adequate justification of a resistance to oppression. He delivers them as he found them, without even appearing to have made them his own by new modifications. The opinion, that the right of the magistrate to obedience is founded in the original delegation of power by the people to the government, is at least as old as the writings of Thomas Aquinas: and in the beginning of the seventeenth century, it was regarded as the common doctrine of all the divines, jurists and philosophers, who had at that time examined the moral foundation of political authority. It then prevailed indeed so universally, Edition: current; Page: [22] that it was assumed by Hobbes as the basis of his system of universal servitude. The divine right of kingly government was a principle very little known, till it was inculcated in the writings of English court divines after the accession of the Stuarts. The purpose of Mr. Locke’s work did not lead him to inquire more anxiously into the solidity of these universally received principles; nor were there at the time any circumstances, in the condition of the country, which could suggest to his mind the necessity of qualifying their application. His object, as he says himself, was “to establish the throne of our great Restorer, our present King William; to make good his title in the consent of the people, which, being the only one of all lawful governments, he has more fully and clearly than any prince in Christendom; and to justify to the world the people of England, whose love of their just and natural rights, with their resolution to preserve them, saved the nation when it was on the very brink of slavery and ruin.” It was essential to his purpose to be exact in his more particular observations: that part of his work is, accordingly, remarkable for general caution, and every where bears marks of his own considerate mind. By calling William “a Restorer,” he clearly points out the characteristic principle of the Revolution; and sufficiently shows that he did not consider it as intended to introduce novelties, but to defend or recover the ancient laws and liberties of the kingdom. In enumerating cases which justify resistance, he confines himself, almost as cautiously as the Bill of Rights, to the grievances actually suffered under the late reign: and where he distinguishes between a dissolution of government and a dissolution of society, it is manifestly his object to guard against those inferences which would have rendered the Revolution a source of anarchy, instead of being the parent of order and security. In one instance only, that of taxation, where he may be thought to have introduced subtle and doubtful speculations into a matter altogether practical, his purpose was to discover an immovable foundation for that ancient principle of rendering the government dependent on the representatives of the people for pecuniary supply, which first established the English Constitution; which improved and strengthened it in a course of ages; and which, at the Revolution, finally triumphed over the conspiracy of the Stuart princes. If he be ever mistaken in his premises, his conclusions at least are, in this part of his work, equally just, generous, and prudent. Whatever charge of haste or inaccuracy may be brought against his abstract principles, he thoroughly weighs, and maturely considers the practical results. Those who consider his moderate plan of Parliamentary Reform as at variance with his theory of government, may perceive, even in this repugnance, whether real or apparent, a new indication of those dispositions which exposed him rather to the reproach of being an inconsistent reasoner, than to that of being a dangerous politician. In such works, however, the nature of the subject has, in some degree, obliged most men of sense to treat it with considerable regard to consequences; though there are memorable and unfortunate examples of an opposite tendency.

The metaphysical object of the Essay on Human Understanding, therefore, illustrates the natural bent of the author’s genius more forcibly than those writings which are connected with the business and interests of men. The reasonable admirers of Mr. Locke would have pardoned Mr. Stewart, if he had pronounced more decisively, that the first book of that work is inferior to the others; and we have satisfactory proof that it was so considered by the author himself, who, in the abridgment of the Essay which he published in Leclerc’s Review, omits it altogether, as intended only to obviate the prejudices of some philosophers against the more important contents of his work. It must be owned, that the very terms “innate ideas” and “innate principles,” together with the division of the latter into “speculative and practical,” are not only vague, but equivocal; that they are capable of different senses; and that they are not always employed in the same sense throughout this discussion. Nay, it will be found very difficult, after the most careful perusal of Mr. Locke’s first book, to state the question in dispute clearly and shortly, in language so strictly philosophical as to be free from any hypothesis. As the antagonists chiefly contemplated by Mr. Locke were the followers of Descartes, perhaps the only proposition for which he must necessarily be held to contend was, that the mind has no ideas which do not arise from impressions on the senses, or from reflections on our own thoughts and feelings. But it is certain, that he sometimes appears to contend for much more than this proposition; that he has generally been understood in a larger sense; and that, thus interpreted, his doctrine is not irreconcilable to those philosophical systems with which it has been supposed to be most at variance.

These general remarks may be illustrated by a reference to some of those ideas which are more general and important, and seem Edition: current; Page: [23] more dark than any others;—perhaps only because we seek in them for what is not to be found in any of the most simple elements of human knowledge. The nature of our notion of space, and more especially of that of time, seems to form one of the mysteries of our intellectual being. Neither of these notions can be conceived separately. Nothing outward can be conceived without space; for it is space which gives outness to objects, or renders them capable of being conceived as outward. Nothing can be conceived to exist, without conceiving some time in which it exists. Thought and feeling may be conceived, without at the same time conceiving space; but no operation of mind can be recalled which does not suggest the conception of a portion of time, in which such mental operation is performed. Both these ideas are so clear that they cannot be illustrated, and so simple that they cannot be defined: nor indeed is it possible, by the use of any words, to advance a single step towards rendering them more, or otherwise intelligible than the lessons of Nature have already made them. The metaphysician knows no more of either than the rustic. If we confine ourselves merely to a statement of the facts which we discover by experience concerning these ideas, we shall find them reducible, as has just been intimated, to the following;—namely, that they are simple; that neither space nor time can be conceived without some other conception; that the idea of space always attends that of every outward object; and that the idea of time enters into every idea which the mind of man is capable of forming. Time cannot be conceived separately from something else; nor can any thing else be conceived separately from time. If we are asked whether the idea of time be innate, the only proper answer consists in the statement of the fact, that it never arises in the human mind otherwise than as the concomitant of some other perception; and that thus understood, it is not innate, since it is always directly or indirectly occasioned by some action on the senses. Various modes of expressing these facts have been adopted by different philosophers, according to the variety of their technical language. By Kant, space is said to be the form of our perceptive faculty, as applied to outward objects; and time is called the form of the same faculty, as it regards our mental operations: by Mr. Stewart, these ideas are considered “as suggested to the understanding” by sensation or reflection, though, according to him, “the mind is not directly and immediately furnished” with such ideas, either by sensation or reflection: and, by a late eminent metaphysician, they were regarded as perceptions, in the nature of those arising from the senses, of which the one is attendant on the idea of every outward object, and the other concomitant with the consciousness of every mental operation. Each of these modes of expression has its own advantages. The first mode brings forward the universality and necessity of these two notions; the second most strongly marks the distinction between them and the fluctuating perceptions naturally referred to the senses; while the last has the opposite merit of presenting to us that incapacity of being analyzed, in which they agree with all other simple ideas. On the other hand, each of them (perhaps from the inherent imperfection of language) seems to insinuate more than the mere results of experience. The technical terms introduced by Kant have the appearance of an attempt to explain what, by the writer’s own principles, is incapable of explanation; Mr. Wedgwood may be charged with giving the same name to mental phenomena, which coincide in nothing but simplicity; and Mr. Stewart seems to us to have opposed two modes of expression to each other, which, when they are thoroughly analyzed, represent one and the same fact.

Leibnitz thought that Locke’s admission of “ideas of reflection” furnished a ground for negotiating a reconciliation between his system and the opinions of those who, in the etymological sense of the word, are more metaphysical; and it may very well be doubted, whether the ideas of Locke much differed from the “innate ideas” of Descartes, especially as the latter philosopher explained the term, when he found himself pressed by acute objectors. “I never said or thought,” says Descartes, “that the mind needs innate ideas, which are something different from its own faculty of thinking; but, as I observed certain thoughts to be in my mind, which neither proceeded from outward objects, nor were determined by my will, but merely from my own faculty of thinking, I called these ‘innate ideas,’ to distinguish them from such as are either adventitious (i. e. from without), or compounded by our imagination. I call them innate, in the same sense in which generosity is innate in some families, gout and stone in others; because the children of such families come into the world with a disposition to such virtue, or to such maladies.” In a letter to Mersenne, he says, “by the word ‘idea,’ I understand all that can be in our thoughts, and I distinguish three sorts of ideas;—adventitious, like the common idea of the sun; framed by the mind, such as that which astronomical reasoning gives us of the sun; and innate, Edition: current; Page: [24] as the idea of God, mind, body, a triangle, and generally all those which represent true, immutable, and eternal essences.” It must be owned, that, however nearly the first of these representations may approach to Mr. Locke’s ideas of reflection, the second deviates from them very widely, and is not easily reconcilable with the first. The comparison of these two sentences, strongly impeaches the steadiness and consistency of Descartes in the fundamental principles of his system.

A principle in science is a proposition from which many other propositions may be inferred. That principles, taken in this sense of propositions, are part of the original structure or furniture of the human mind, is an assertion so unreasonable, that perhaps no philosopher has avowedly, or at least permanently, adopted it. But it is not to be forgotten, that there must be certain general laws of perception, or ultimate facts respecting that province of mind, beyond which human knowledge cannot reach. Such facts bound our researches in every part of knowledge, and the ascertainment of them is the utmost possible attainment of Science. Beyond them there is nothing, or at least nothing discoverable by us. These observations, however universally acknowledged when they are stated, are often hid from the view of the system-builder when he is employed in rearing his airy edifice. There is a common disposition to exempt the philosophy of the human understanding from the dominion of that irresistible necessity which confines all other knowledge within the limits of experience;—arising probably from a vague notion that the science, without which the principles of no other are intelligible, ought to be able to discover the foundation even of its own principles. Hence the question among the German metaphysicians, “What makes experience possible?” Hence the very general indisposition among metaphysicians to acquiesce in any mere fact as the result of their inquiries, and to make vain exertions in pursuit of an explanation of it, without recollecting that the explanation must always consist of another fact, which must either equally require another explanation, or be equally independent of it. There is a sort of sullen reluctance to be satisfied with ultimate facts, which has kept its ground in the theory of the human mind long after it has been banished from all other sciences. Philosophers are, in this province, often led to waste their strength in attempts to find out what supports the foundation; and, in these efforts to prove first principles, they inevitably find that their proof must contain an assumption of the thing to be proved, and that their argument must return to the point from which it set out.

Mental philosophy can consist of nothing but facts; and it is at least as vain to inquire into the cause of thought, as into the cause of attraction. What the number and nature of the ultimate facts respecting mind may be, is a question which can only be determined by experience: and it is of the utmost importance not to allow their arbitrary multiplication, which enables some individuals to impose on us their own erroneous or uncertain speculations as the fundamental principles of human knowledge. No general criterion has hitherto been offered, by which these last principles may be distinguished from all other propositions. Perhaps a practical standard of some convenience would be, that all reasoners should be required to admit every principle of which the denial renders reasoning impossible. This is only to require that a man should admit, in general terms, those principles which he must assume in every particular argument, and which he has assumed in every argument which he has employed against their existence. It is, in other words, to require that a disputant shall not contradict himself; for every argument against the fundamental laws of thought absolutely assumes their existence in the premises, while it totally denies it in the conclusion.

Whether it be among the ultimate facts in human nature, that the mind is disposed or determined to assent to some propositions, and to reject others, when they are first submitted to its judgment, without inferring their truth or falsehood from any process of reasoning, is manifestly as much a question of mere experience as any other which relates to our mental constitution. It is certain that such inherent inclinations may be conceived, without supposing the ideas of which the propositions are composed to be, in any sense, ‘innate’; if, indeed, that unfortunate word be capable of being reduced by definition to any fixed meaning. “Innate,” says Lord Shaftesbury, “is the word Mr. Locke poorly plays with: the right word, though less used, is connate. The question is not about the time when the ideas enter the mind, but, whether the constitution of man be such, as at some time or other (no matter when), the ideas will not necessarily spring up in him.” These are the words of Lord Shaftesbury in his Letters, which, not being printed in any edition of the Characteristics, are less known than they ought to be; though, in them, the fine genius and generous principles of the writer are less hid by occasional affectation of style, than in any other of his writings.

The above observations apply with still greater force to what Mr. Locke calls “practical principles.” Here, indeed, he contradicts himself; for, having built one of his chief arguments against other speculative or practical principles, on what he thinks the incapacity of the majority of mankind to entertain those very abstract ideas, of which these principles, if innate, would imply the presence in every mind, he very inconsistently Edition: current; Page: [25] admits the existence of one innate practical principle,—“a desire of happiness, and an aversion to misery,” without considering that happiness and misery are also abstract terms, which excite very indistinct conceptions in the minds of “a great part of mankind.” It would be easy also to show, if this were a proper place, that the desire of happiness, so far from being an innate, is not even an original principle; that it presupposes the existence of all those particular appetites and desires of which the gratification is pleasure, and also the exercise of that deliberate reason which habitually examines how far each gratification, in all its consequences, increases or diminishes that sum of enjoyment which constitutes happiness. If that subject could be now fully treated, it would appear that this error of Mr. Locke, or another equally great, that we have only one practical principle,—the desire of pleasure,—is the root of most false theories of morals; and that it is also the source of many mistaken speculations on the important subjects of government and education, which at this moment mislead the friends of human improvement, and strengthen the arms of its enemies. But morals fell only incidentally under the consideration of Mr. Locke, and his errors on that greatest of all sciences were the prevalent opinions of his age, which cannot be justly called the principles of Hobbes, though that extraordinary man had alone the boldness to exhibit these principles in connexion with their odious but strictly logical consequences.

The exaggerations of this first book, however, afford a new proof of the author’s steady regard to the highest interests of mankind. He justly considered the free exercise of reason as the highest of these, and that on the security of which all the others depend. The circumstances of his life tendered it a long warfare against the enemies of freedom in philosophising, freedom in worship, and freedom from every political restraint which necessity did not justify. In his noble zeal for liberty of thought, he dreaded the tendency of a doctrine which might “gradually prepare mankind to swallow that for an innate principle which may serve his purpose who teacheth them.” He may well be excused, if, in the ardour of his generous conflict, he sometimes carried beyond the bounds of calm and neutral reason his repugnance to doctrines which, as they were then generally explained, he justly regarded as capable of being employed to shelter absurdity from detection, to stop the progress of free inquiry, and to subject the general reason to the authority of a few individuals. Every error of Mr. Locke in speculation may be traced to the influence of some virtue;—at least every error except some of the erroneous opinions generally received in his age, which, with a sort of passive acquiescence, he suffered to retain their place in his mind.

It is with the second book that the Essay on the Human Understanding properly begins; and this book is the first considerable contribution in modern times towards the experimental philosophy of the human mind. The road was pointed out by Bacon; and, by excluding the fallacious analogies of thought to outward appearance, Descartes may be said to have marked out the limits of the proper field of inquiry. But, before Locke, there was no example in intellectual philosophy of an ample enumeration of facts, collected and arranged for the express purpose of legitimate generalization. He himself tells us, that his purpose was, “in a plain historical method, to give an account of the ways by which our understanding comes to attain those notions of things we have.” In more modern phraseology, this would be called an attempt to ascertain, by observation, the most general facts relating to the origin of human knowledge. There is something in the plainness, and even homeliness of Locke’s language, which strongly indicates his very clear conception, that experience must be his sole guide, and his unwillingness, by the use of scholastic language, to imitate the example of those who make a show of explaining facts, while in reality they only “darken counsel by words without knowledge.” He is content to collect the laws of thought, as he would have collected those of any other object of physical knowledge, from observation alone. He seldom embarrasses himself with physiological hypothesis, or wastes his strength on those Edition: current; Page: [26] insoluble problems which were then called metaphysical. Though, in the execution of his plan, there are many and great defects, the conception of it is entirely conformable to the Verulamian method of induction, which, even after the fullest enumeration of particulars, requires a cautious examination of each subordinate class of phenomena, before we attempt, through a very slowly ascending series of generalizations, to soar to comprehensive laws. “Philosophy,” as Mr. Playfair excellently renders Bacon, “has either taken much from a few things, or too little from a great many; and in both cases has too narrow a basis to be of much duration or utility.” Or, to use the very words of the Master himself—“We shall then have reason to hope well of the sciences, when we rise by continued steps from particulars to inferior axioms, and then to the middle, and only at last to the most general. It is not so much by an appeal to experience (for some degree of that appeal is universal), as by the mode of conducting it, that the followers of Bacon are distinguished from the framers of hypotheses.” It is one thing to borrow from experience just enough to make a supposition plausible; it is quite another to take from it all that is necessary to be the foundation of just theory.

In this respect perhaps, more than in any other, the philosophical writings of Locke are contradistinguished from those of Hobbes. The latter saw, with astonishing rapidity of intuition some of the simplest and most general facts which may be observed in the operations of the understanding, and perhaps no man ever possessed the same faculty of conveying his abstract speculations in language of such clearness, precision, and force, as to engrave them on the mind of the reader. But he did not wait to examine whether there might not be other facts equally general relating to the intellectual powers, and he therefore “took too little from a great many things.” He fell into the double error of hastily applying his general laws to the most complicated processes of thought, without considering whether these general laws were not themselves limited by other not less comprehensive laws, and without trying to discover how they were connected with particulars, by a scale of intermediate and secondary laws. This mode of philosophising was well suited to the dogmatic confidence and dictatorial tone which belonged to the character of the philosopher of Malmsbury, and which enabled him to brave the obloquy attendant on singular and obnoxious opinions. “The plain historical method,” on the other hand, chosen by Mr. Locke, produced the natural fruits of caution and modesty; taught him to distrust hasty and singular conclusions; disposed him, on fit occasions, to entertain a mitigated scepticism; and taught him also the rare courage to make an ingenuous avowal of ignorance. This contrast is one of our reasons for doubting whether Locke be much indebted to Hobbes for his speculations; and certainly the mere coincidence of the opinions of two metaphysicians is slender evidence, in any case, that either of them has borrowed his opinions from the other. Where the premises are different, and they have reached the same conclusion by different roads, such a coincidence is scarcely any evidence at all. Locke and Hobbes agree chiefly on those points in which, except the Cartesians, all the speculators of their age were also agreed. They differ on the most momentous questions,—the sources of knowledge,—the power of abstraction,—the nature of the will; on the two last of which subjects, Locke, by his very failures themselves, evinces a strong repugnance to the doctrines of Hobbes. They differ not only in all their premises, and many of their conclusions, but in their manner of philosophising itself. Locke had no prejudice which could lead him to imbibe doctrines from the enemy of liberty and religion. His style, with all its faults, is that of a man who thinks for himself; and an original style is not usually the vehicle of borrowed opinions.

Few books have contributed more than Mr. Locke’s Essay to rectify prejudice, to undermine established errors, to diffuse a just mode of thinking; to excite a fearless spirit of inquiry, and yet to contain it within the boundaries which Nature has prescribed to the human understanding. An amendment of the general habits of thought is, in most parts of knowledge, an object as important as even the discovery of new truths; though it is not so palpable, nor in its nature so capable of being estimated by superficial observers. In the mental and moral world, which scarcely admits of any thing which can be called discovery, the correction of the intellectual habits is probably the greatest service which can be rendered to Science. In this respect, the merit of Locke is unrivalled. His writings have diffused throughout the civilized world, the love of civil liberty and the spirit of toleration and charity in religious differences, with the disposition to reject whatever is obscure, fantastic, or hypothetical in speculation,—to reduce verbal disputes to their proper value,—to abandon problems which admit of no solution,—to distrust whatever cannot clearly be expressed,—to render theory the simple expression of facts,—and to prefer those studies which most directly contribute to human happiness. If Bacon first discovered the rules by which knowledge is improved, Locke has most contributed to make mankind at large observe them. He has done most, though often by remedies of silent and almost insensible operation, to cure those mental distempers which obstructed the adoption of these rules; and has thus led to that general diffusion of a healthful and vigorous understanding, which is at once the greatest of all improvements, and the Edition: current; Page: [27] instrument by which all other progress must be accomplished. He has left to posterity the instructive example of a prudent reformer, and of a philosophy temperate as well as liberal, which spares the feelings of the good, and avoids direct hostility with obstinate and formidable prejudice. These benefits are very slightly counterbalanced by some political doctrines liable to misapplication, and by the scepticism of some of his ingenious followers;—an inconvenience to which every philosophical school is exposed, which does not steadily limit its theory to a mere exposition of experience. If Locke made few discoveries, Socrates made none: yet both did more for the improvement of the understanding, and not less for the progress of knowledge, than the authors of the most brilliant discoveries. Mr. Locke will ever be regarded as one of the great ornaments of the English nation; and the most distant posterity will speak of him in the language addressed to him by the poet—

- “O Decus Angliacæ certè, O Lux altera gentis!”

A DISCOURSE ON THE LAW OF NATURE AND NATIONS.

Before I begin a course of lectures on a science of great extent and importance, I think it my duty to lay before the public the reasons which have induced me to undertake such a labour, as well as a short account of the nature and objects of the course which I propose to deliver. I have always been unwilling to waste in unprofitable inactivity that leisure which the first years of my profession usually allow, and which diligent men, even with moderate talents, might often employ in a manner neither discreditable to themselves, nor wholly useless to others. Desirous that my own leisure should not be consumed in sloth, I anxiously looked about for some way of filling it up, which might enable me according to the measure of my humble abilities, to contribute somewhat to the stock of general usefulness. I had long been convinced that public lectures, which have been used in most ages and countries to teach the elements of almost every part of learning, were the most convenient mode in which these elements could be taught;—that they were the best adapted for the important purposes of awakening the attention of the student, of abridging his labours, of guiding his inquiries, of relieving the tediousness of private study, and of impressing on his recollection the principles of a science. I saw no reason why the law of England should be less adapted to this mode of instruction, or less likely to benefit by it, than any other part of knowledge. A learned gentleman, however, had already occupied that ground, and will, I doubt not, persevere in the useful labour which he has undertaken. On his province it was far from my wish to intrude. It appeared to me that a course of lectures on another science closely connected with all liberal professional studies, and which had long been the subject of my own reading and reflection, might not only prove a most useful introduction to the law of England, but might also become an interesting part of general study, and an important branch of the education of those who were not destined for the profession of the law. I was confirmed in my opinion by the assent and approbation of men, whose names, if it were becoming to mention them on so slight an occasion, would add authority to truth, and furnish some excuse even for error. Encouraged by their approbation, I resolved without delay to commence the undertaking, of which I shall now proceed to give some account; without interrupting the progress of my discourse by anticipating or answering the remarks of those who may, perhaps, sneer at me for a departure from the usual course of my profession, because I am desirous of employing in a rational and useful pursuit that leisure, of which the same men would have required no account, if it had been wasted on trifles, or even abused in dissipation.

The science which teaches the rights and duties of men and of states, has, in modern times, been called “the law of nature and nations.” Under this comprehensive title Edition: current; Page: [28] are included the rules of morality, as they prescribe the conduct of private men towards each other in all the various relations of human life; as they regulate both the obedience of citizens to the laws, and the authority of the magistrate in framing laws, and administering government, and as they modify the intercourse of independent commonwealths in peace, and prescribe limits to their hostility in war. This important science comprehends only that part of private ethics which is capable of being reduced to fixed and general rules. It considers only those general principles of jurisprudence and politics which the wisdom of the lawgiver adapts to the peculiar situation of his own country, and which the skill of the statesman applies to the more fluctuating and infinitely varying circumstances which affect its immediate welfare and safety. “For there are in nature certain fountains of justice whence all civil laws are derived, but as streams; and like as waters do take tinctures and tastes from the soils through which they run, so do civil laws vary according to the regions and governments where they are planted, though they proceed from the same fountains.”

On the great questions of morality, of politics, and of municipal law, it is the object of this science to deliver only those fundamental truths of which the particular application is as extensive as the whole private and public conduct of men;—to discover those “fountains of justice,” without pursuing the “streams” through the endless variety of their course. But another part of the subject is to be treated with greater fulness and minuteness of application; namely, that important branch of it which professes to regulate the relations and intercourse of states, and more especially, (both on account of their greater perfection and their more immediate reference to use), the regulations of that intercourse as they are modified by the usages of the civilized nations of Christendom. Here this science no longer rests on general principles. That province of it which we now call the “law of nations,” has, in many of its parts, acquired among European ones much of the precision and certainty of positive law; and the particulars of that law are chiefly to be found in the works of those writers who have treated the science of which I now speak. It is because they have classed (in a manner which seems peculiar to modern times) the duties of individuals with those of nations, and established their obligation on similar grounds, that the whole science has been called, “the law of nature and nations.”

Whether this appellation be the happiest that could have been chosen for the science, and by what steps it came to be adopted among our modern moralists and lawyers, are inquiries, perhaps, of more curiosity than use, and ones which, if they deserve any where to be deeply pursued, will be pursued with more propriety in a full examination of the subject than within the short limits of an introductory discourse. Names are, however, in a great measure arbitrary; but the distribution of knowledge into its parts, though it may often perhaps be varied with little disadvantage, yet certainly depends upon some fixed principles. The modern method of considering individual and national morality as the subjects of the same science, seems to me as convenient and reasonable an arrangement as can be adopted. The same rules of morality which hold together men in families, and which form families into commonwealths, also link together these commonwealths as members of the great society of mankind. Commonwealths, as well as private men, are liable to injury, and capable of benefit, from each other; it is, therefore, their interest, as well as their duty, to reverence, to practise, and to enforce those rules of justice which control and restrain injury,—which regulate and augment benefit,—which, even in their present imperfect observance, preserve civilized states in a tolerable condition of security from wrong, and which, if they could be generally obeyed, would establish, and permanently maintain, the well-being of the universal commonwealth of the human race. It is therefore with justice, that one part of this science has been called “the natural law of individuals,” and the other “the natural law of states;” and it is too obvious to require observation, that the application of both these laws, of the former as much as of the latter, is modified and varied by customs, Edition: current; Page: [29] conventions, character, and situation. With a view to these principles, the writers on general jurisprudence have considered states as moral persons; a mode of expression which has been called a fiction of law, but which may be regarded with more propriety as a bold metaphor, used to convey the important truth, that nations, though they acknowledge no common superior, and neither can, nor ought, to be subjected to human punishment, are yet under the same obligations mutually to practise honesty and humanity, which would have bound individuals,—if the latter could be conceived ever to have subsisted without the protecting restraints of government, and if they were not compelled to the discharge of their duty by the just authority of magistrates, and by the wholesome terrors of the laws. With the same views this law has been styled, and (notwithstanding the objections of some writers to the vagueness of the language) appears to have been styled with great propriety, “the law of nature.” It may with sufficient correctness, or at least by an easy metaphor, be called a “law,” masmuch as it is a supreme, invariable, and uncontrollable rule of conduct to all men, the violation of which is avenged by natural punishments, necessarily flowing from the constitution of things, and as fixed and inevitable as the order of nature. It is “the law of nature,” because its general precepts are essentially adapted to promote the happiness of man, as long as he remains a being of the same nature with which he is at present endowed, or, in other words, as long as he continues to be man, in all the variety of times, places, and circumstances, in which he has been known, or can be imagined to exist; because it is discoverable by natural reason, and suitable to our natural constitution; and because its fitness and wisdom are founded on the general nature of human beings, and not on any of those temporary and accidental situations in which they may be placed. It is with still more propriety, and indeed with the highest strictness, and the most perfect accuracy, considered as a law, when, according to those just and magnificent views which philosophy and religion open to us of the government of the world, it is received and reverenced as the sacred code, promulgated by the great Legislator of the Universe for the guidance of His creatures to happiness,—guarded and enforced, as our own experience may inform us, by the penal sanctions of shame, of remorse, of infamy, and of misery; and still farther enforced by the reasonable expectation of yet more awful penalties in a future and more permanent state of existence. It is the contemplation of the law of nature under this full, mature, and perfect idea of its high origin and transcendent dignity, that called forth the enthusiasm of the greatest men, and the greatest writers of ancient and modern times, in those sublime descriptions, in which they have exhausted all the powers of language, and surpassed all the other exertions, even of their own eloquence, in the display of its beauty and majesty. It is of this law that Cicero has spoken in so many parts of his writings, not only with all the splendour and copiousness of eloquence, but with the sensibility of a man of virtue, and with the gravity and comprehension of a philosopher. It is of this law that Hooker speaks in so sublime a strain:—“Of Law, no less can be said, than that her seat is the bosom of God, her voice the harmony of the world, all things in heaven and earth do her homage, the very least as feeling her care, the greatest as not exempted from her power; both angels and men, and creatures of what condition soever, though each in different sort and manner, yet all with uniform consent admiring her as the mother of their peace and joy.”

Let not those who, to use the language of the same Hooker, “talk of truth,” without “ever sounding the depth from whence it springeth,” hastily take it for granted, that these great masters of eloquence and reason were led astray by the specious delusions of mysticism, from the sober consideration of the true grounds of morality in the nature, necessities, and interests of man. They studied and taught the principles of morals; but they thought it still more necessary, and more wise,—a much nobler task, and more becoming a true philosopher, to inspire men with a love and reverence for virtue. They were not contented with elementary speculations: they examined the foundations of our duty; but they felt and cherished a most natural, a most seemly, a most rational enthusiasm, when they contemplated the majestic edifice which is reared on these solid foundations. They devoted the highest exertions of their minds to spread that beneficent enthusiasm among men. They consecrated as a homage to Virtue the most perfect Edition: current; Page: [30] fruits of their genius. If these grand sentiments of “the good and fair” have sometimes prevented them from delivering the principles of ethics with the nakedness and dryness of science, at least we must own that they have chosen the better part,—that they have preferred virtuous feeling to moral theory, and practical benefit to speculative exactness. Perhaps these wise men may have supposed that the minute dissection and anatomy of Virtue might, to the ill-judging eye, weaken the charm of her beauty.

It is not for me to attempt a theme which has perhaps been exhausted by these great writers. I am indeed much less called upon to display the worth and usefulness of the law of nations, than to vindicate myself from presumption in attempting a subject which has been already handled by so many masters. For the purpose of that vindication it will be necessary to sketch a very short and slight account (for such in this place it must unavoidably be) of the progress and present state of the science, and of that succession of able writers who have gradually brought it to its present perfection.

We have no Greek or Roman treatise remaining on the law of nations. From the title of one of the lost works of Aristotle, it appears that he composed a treatise on the laws of war, which, if we had the good fortune to possess it, would doubtless have amply satisfied our curiosity, and would have taught us both the practice of the ancient nations and the opinions of their moralists, with that depth and precision which distinguish the other works of that great philosopher. We can now only imperfectly collect that practice and those opinions from various passages which are scattered over the writings of philosophers, historians, poets, and orators. When the time shall arrive for a more full consideration of the state of the government and manners of the ancient world, I shall be able, perhaps, to offer satisfactory reasons why these enlightened nations did not separate from the general province of ethics that part of morality which regulates the intercourse of states, and erect it into an independent science. It would require a long discussion to unfold the various causes which united the modern nations of Europe into a closer society,—which linked them together by the firmest bands of mutual dependence, and which thus, in process of time, gave to the law that regulated their intercourse, greater importance, higher improvement, and more binding force. Among these causes, we may enumerate a common extraction, a common religion, similar manners, institutions, and languages; in earlier ages the authority of the See of Rome, and the extravagant claims of the imperial crown; in latter times the connexions of trade, the jealousy of power, the refinement of civilization, the cultivation of science, and, above all, that general mildness of character and manners which arose from the combined and progressive influence of chivalry, of commerce, of learning and of religion. Nor must we omit the similarity of those political institutions which, in every country that had been overrun by the Gothic conquerors, bore discernible marks (which the revolutions of succeeding ages had obscured, but not obliterated) of the rude but bold and noble outline of liberty that was originally sketched by the hand of these generous barbarians. These and many other causes conspired to unite the nations of Europe in a more intimate connexion and a more constant intercourse, and, of consequence, made the regulation of their intercourse more necessary, and the law that was to govern it more important. In proportion as they approached to the condition of provinces of the same empire, it became almost as essential that Europe should have a precise and comprehensive code of the law of nations, as that each country should have a system of municipal law. The labours of the learned, accordingly, began to be directed to this subject in the sixteenth century, soon after the revival of learning, and after that regular distribution of power and territory which has subsisted, with little variation, until our times. The critical examination of these early writers would, perhaps, not be very interesting in an extensive work, and it would be unpardonable in a short discourse. It is sufficient to observe that they were all more or less shackled by the barbarous philosophy of the schools, and that they were impeded in their progress by a timorous deference for the inferior and technical parts of the Roman law, without raising then views to the comprehensive principles which will for ever inspire mankind with veneration for that grand monument of human wisdom. It was only, indeed, in the sixteenth century that the Roman law was first studied and understood as a science connected with Roman history and literature, and illustrated by men whom Ulpian and Papinian would not have disdained to acknowledge as their successors. Among the writers of that age we may perceive the ineffectual attempts, the partial advances, the occasional streaks of light which always precede great discoveries, and works that are to instruct posterity.

The reduction of the law of nations to a system was reserved for Grotius. It was by the advice of Lord Bacon and Peiresc that he undertook this arduous task. He produced a work which we now, indeed, justly deem imperfect, but which is perhaps the most complete that the world has yet owed, at so early a stage in the progress of any science, to the Edition: current; Page: [31] genius and learning of one man. So great is the uncertainty of posthumous reputation, and so liable is the fame even of the greatest men to be obscured by those new fashions of thinking and writing which succeed each other so rapidly among polished nations, that Grotius, who filled so large a space in the eye of his contemporaries, is now perhaps known to some of my readers only by name. Yet if we fairly estimate both his endowments and his virtues, we may justly consider him as one of the most memorable men who have done honour to modern times. He combined the discharge of the most important duties of active and public life with the attainment of that exact and various learning which is generally the portion only of the recluse student. He was distinguished as an advocate and a magistrate, and he composed the most valuable works on the law of his own country; he was almost equally celebrated as an historian, a scholar, a poet, and a divine;—a disinterested statesman, a philosophical lawyer, a patriot who united moderation with firmness, and a theologian who was taught candour by his learning Unmerited exile did not damp his patriotism; the bitterness of controversy did not extinguish his charity. The sagacity of his numerous and fierce adversaries could not discover a blot on his character; and in the midst of all the hard trials and galling provocations of a turbulent political life, he never once deserted his friends when they were unfortunate, nor insulted his enemies when they were weak. In times of the most furious civil and religious faction he preserved his name unspotted, and he knew how to reconcile fidelity to his own party, with moderation towards his opponents.

Such was the man who was destined to give a new form to the law of nations, or rather to create a science, of which only rude sketches and undigested materials were scattered over the writings of those who had gone before him. By tracing the laws of his country to then principles, he was led to the contemplation of the law of nature, which he justly considered as the parent of all municipal law. Few works were more celebrated than that of Grotius in his own days, and in the age which succeeded. It has, however, been the fashion of the last half-century to depreciate his work as a shapeless compilation, in which reason lies buried under a mass of authorities and quotations. This fashion originated among French wits and declaimers, and it has been, I know not for what reason, adopted, though with far greater moderation and decency, by some respectable writers among ourselves. As to those who first used this language, the most candid supposition that we can make with respect to them is, that they never read the work; for, if they had not been deterred from the perusal of it by such a formidable display of Greek characters, they must soon have discovered that Grotius never quotes on any subject till he has first appealed to some principles, and often, in my humble opinion, though not always, to the soundest and most rational principles.

But another sort of answer is due to some of those who have criticised Grotius, and that answer might be given in the words of Grotius himself. He was not of such a stupid and servile cast of mind, as to quote the opinions of poets or orators, of historiaus and philosophers, as those of judges, from whose decision there was no appeal. He quotes them, as he tells us himself, as witnesses whose conspiring testimony, mightily strengthened and confirmed by their discordance on almost every other subject, is a conclusive proof of the unanimity of the whole human race on the great rules of duty and the fundamental principles of morals. On such matters, poets and orators are the most unexceptionable of all witnesses; for they address themselves to the general feelings and sympathies of mankind; they are neither warped by system, nor perverted by sophistry; they can attain none of then objects, they can neither please nor persuade, if they dwell on moral sentiments not in unison with those of their readers. No system of moral philosophy can surely disregaid the general feelings of human nature and the according judgment of all ages and nations. But where are these feelings and that judgment recorded and preserved? In those very writings which Grotius is gravely blamed for having quoted. The usages and laws of nations, the events of history, the opinions of philosophers, the sentiments of orators and poets, as well as the observation of common life, are, in truth, the materials out of which the science of morality is formed; and those who neglect them are justly chargeable with a vain attempt to philosophise without regard to fact and experience,—the sole foundation of all true philosophy.

If this were merely an objection of taste, I should be willing to allow that Grotius has indeed poured forth his learning with a profusion that sometimes rather encumbers than adorns his work, and which is not always necessary to the illustration of his subject. Yet, even in making that concession, I should rather yield to the taste of others than speak from my own feelings. I own that such richness and splendour of literature have a powerful charm for me. They fill my mind with an endless variety of delightful recollections and associations. They relieve the understanding in its progress through a vast science, by calling up the memory of great men and of interesting events. By this means we see the truths of morality clothed with all the eloquence,—not that could be produced by the powers of one man,—but that could be bestowed on them by the collective Edition: current; Page: [32] genius of the world. Even Virtue and Wisdom themselves acquire new majesty in my eyes, when I thus see all the great masters of thinking and writing called together, as it were, from all times and countries, to do them homage, and to appear in their train.

But this is no place for discussions of taste, and I am very ready to own that mine may be corrupted. The work of Grotius is liable to a more serious objection, though I do not recollect that it has ever been made. His method is inconvenient and unscientific: he has inverted the natural order. That natural order undoubtedly dictates, that we should first search for the original principles of the science in human nature; then apply them to the regulation of the conduct of individuals; and lastly, employ them for the decision of those difficult and complicated questions that arise with respect to the intercourse of nations. But Grotius has chosen the reverse of this method. He begins with the consideration of the states of peace and war, and he examines original principles only occasionally and incidentally, as they grow out of the questions which he is called upon to decide. It is a necessary consequence of this disorderly method,—which exhibts the elements of the science in the form of scattered digressions, that he seldom employs sufficient discussion on these fundamental truths, and never in the place where such a discussion would be most instructive to the reader.

This defect in the plan of Grotius was perceived and supplied by Puffendorff, who restored natural law to that superiority which belonged to it, and, with great propriety, treated the law of nations as only one main branch of the parent stock. Without the genius of his master, and with very inferior learning, he has yet treated this subject with sound sense, with clear method, with extensive and accurate knowledge, and with a copiousness of detail sometimes indeed tedious, but always instructive and satisfactory. His work will be always studied by those who spare no labour to acquire a deep knowledge of the subject; but it will, in our times, I fear, be oftener found on the shelf than on the desk of the general student. In the time of Mr. Locke it was considered as the manual of those who were intended for active life; but in the present age, I believe it will be found that men of business are too much occupied,—men of letters are too fastidious, and men of the world too indolent, for the study or even the perusal of such works. Far be it from me to derogate from the real and great merit of so useful a writer as Puffendorff. His treatise is a mine in which all his successors must dig. I only presume to suggest, that a book so prolix, and so utterly void of all the attractions of composition, is likely to repel many readers who are interested in its subject, and who might perhaps be disposed to acquire some knowledge of the principles of public law.