CORRESPONDENCE AND MISCELLANEOUS WRITINGS

Edition: current; Page: [2]

Edition: current; Page: [3]

CCCXXXIV

TO M. DUBOURG

I am apprehensive that I shall not be able to find leisure for making all the disquisitions and experiments which would be desirable on this subject. I must, therefore, content myself with a few remarks.

The specific gravity of some human bodies, in comparison to that of water, has been examined by Mr. Robinson, in our Philosophical Transactions, Volume L., page 30, for the year 1757. He asserts that fat persons with small bones float most easily upon the water.

The diving-bell is accurately described in our Transactions.

When I was a boy I made two oval palettes, each about ten inches long and six broad, with a hole for the thumb, in order to retain it fast in the palm of my hand. They much resembled a painter’s palettes. Edition: current; Page: [4] In swimming I pushed the edges of these forward, and I struck the water with their flat surfaces as I drew them back. I remember I swam faster by means of these palettes, but they fatigued my wrists. I also fitted to the soles of my feet a kind of sandals; but I was not satisfied with them, because I observed that the stroke is partly given by the inside of the feet and the ankles, and not entirely with the soles of the feet.

We have here waistcoats for swimming, which are made of double sail-cloth, with small pieces of cork quilted in between them.

I know nothing of the scaphandre of M. de la Chapelle.

I know by experience that it is a great comfort to a swimmer who has a considerable distance to go, to turn himself sometimes on his back, and to vary in other respects the means of procuring a progressive motion.

When he is seized with the cramp in the leg, the method of driving it away is, to give to the parts affected a sudden, vigorous, and violent shock; which he may do in the air as he swims on his back.

During the great heats of summer there is no danger in bathing, however warm we may be, in rivers which have been thoroughly warmed by the sun. But to throw one’s self into cold spring water, when the body has been heated by exercise in the sun, is an imprudence which may prove fatal. I once knew an instance of four young men who, having worked at harvest in the heat of the day, with a view of refreshing themselves plunged into a spring of Edition: current; Page: [5] cold water; two died upon the spot, a third the next morning, and the fourth recovered with great difficulty. A copious draught of cold water, in similar circumstances, is frequently attended with the same effect in North America.

The exercise of swimming is one of the most healthy and agreeable in the world. After having swam for an hour or two in the evening, one sleeps coolly the whole night, even during the most ardent heat of summer. Perhaps, the pores being cleansed, the insensible perspiration increases and occasions this coolness. It is certain that much swimming is the means of stopping a diarrhœa, and even of producing a constipation. With respect to those who do not know how to swim, or who are affected with a diarrhœa at a season which does not permit them to use that exercise, a warm bath, by cleansing and purifying the skin, is found very salutary, and often effects a radical cure. I speak from my own experience, frequently repeated, and that of others, to whom I have recommended this.

You will not be displeased if I conclude these hasty remarks by informing you that as the ordinary method of swimming is reduced to the act of rowing with the arms and legs, and is consequently a laborious and fatiguing operation when the space of water to be crossed is considerable, there is a method in which a swimmer may pass to a great distance with much facility, by means of a sail. This discovery I fortunately made by accident, and in the following manner:

When I was a boy I amused myself one day with Edition: current; Page: [6] flying a paper kite; and approaching the bank of a pond, which was near a mile broad, I tied the string to a stake and the kite ascended to a very considerable height above the pond while I was swimming. In a little time, being desirous of amusing myself with my kite, and enjoying at the same time the pleasure of swimming, I returned, and loosing from the stake the string with the little stick which was fastened to it, went again into the water, where I found that, lying on my back and holding the stick in my hands, I was drawn along the surface of the water in a very agreeable manner. Having then engaged another boy to carry my clothes round the pond, to a place which I pointed out to him on the other side, I began to cross the pond with my kite, which carried me quite over without the least fatigue, and with the greatest pleasure imaginable. I was only obliged occasionally to halt a little in my course and resist its progress when it appeared that, by following too quick, I lowered the kite too much; by doing which occasionally I made it rise again. I have never since that time practised this singular mode of swimming, though I think it not impossible to cross in this manner from Dover to Calais. The packet-boat, however, is still preferable.

CCCXXXV

TO JOHN WINTHROP

You must needs think the time long that your instruments have been in hand. Sundry Edition: current; Page: [7] circumstances have occasioned the delay. Mr. Short, who undertook to make the telescope, was long in a bad state of health, and much in the country for the benefit of the air. He however at length finished the material parts that required his own hand, and waited only for something about the mounting that was to have been done by another workman, when he was removed by death. I have put in my claim to the instrument, and shall obtain it from the executors as soon as his affairs can be settled. It is now become much more valuable than it would have been if he had lived, as he excelled all others in that branch. The price agreed for was one hundred pounds.

The equal altitudes and transit instrument was undertaken by Mr. Bird, who doing all his work with his own hands for the sake of greater truth and exactness, one must have patience that expects any thing from him. He is so singularly eminent in his way, that the commissioners of longitude have lately given him five hundred pounds merely to discover and make public his method of dividing instruments. I send it you herewith. But what has made him longer in producing your instrument is the great and hasty demand on him from France and Russia, and our Society here, for instruments to go to different parts of the world for observing the next transit of Venus; some to be used in Siberia, some for the observers that go to the South Seas, some for those that go to Hudson’s Bay. These are now all completed and mostly gone, it being necessary, on account of the distance, that they should go this year to be ready Edition: current; Page: [8] on the spot in time. And now he tells me he can finish yours, and that I shall have it next week. Possibly he may keep his word. But we are not to wonder if he does not.

Mr. Martin, when I called to see his panopticon, had not one ready; but was to let me know when he should have one to show me. I have not since heard from him, but will call again.

Mr. Maskelyne wishes much that some of the governments in North America would send an astronomer to Lake Superior to observe this transit. I know no one of them likely to have a spirit for such an undertaking, unless it be the Massachusetts, or that have a person and instruments suitable. He presents you one of his pamphlets, which I now send you, together with two letters from him to me relating to that observation. If your health and strength were sufficient for such an expedition, I should be glad to hear you had taken it. Possibly you may have an élève that is capable. The fitting you out to observe the former transit, was a public act for the benefit of science, that did your province great honor.

We expect soon a new volume of the Transactions, in which your piece will be printed. I have not yet got the separate ones which I ordered.

It is perhaps not so extraordinary that unlearned men, such as commonly compose our church vestries, should not yet be acquainted with, and sensible of the benefits of metal conductors in averting the stroke of lightning, and preserving our houses from its violent effects, or that they should be still prejudiced against the use of such conductors, when we Edition: current; Page: [9] see how long even philosophers, men of extensive science and great ingenuity, can hold out against the evidence of new knowledge that does not square with their preconceptions; and how long men can retain a practice that is conformable to their prejudices, and expect a benefit from such practice though constant experience shows its inutility. A late piece of the Abbé Nollet, printed last year in the Memoirs of the French Academy of Sciences, affords strong instances of this; for, though the very relations he gives of the effects of lightning in several churches and other buildings show clearly that it was conducted from one part to another by wires, gildings, and other pieces of metal that were within or connected with the building, yet in the same paper he objects to the providing metalline conductors without the building, as useless or dangerous. He cautions people not to Edition: current; Page: [10] ring the church bells during a thunder-storm, lest the lightning, in its way to the earth, should be conducted down to them by the bell-ropes, which are but bad conductors, and yet is against fixing metal rods on the outside of the steeple, which are known to be much better conductors, and which it would certainly choose to pass in, rather than in dry hemp. And, though for a thousand years past bells have been solemnly consecrated by the Romish Church, in expectation that the sound of such blessed bells would drive away the storms, and secure our buildings from the stroke of lightning; and during so long a period, Edition: current; Page: [11] it has not been found by experience that places within the reach of such blessed sound are safer than others where it is never heard; but that, on the contrary, the lightning seems to strike steeples of choice, and that at the very time the bells are ringing; yet still they continue to bless the new bells, and jangle the old ones whenever it thunders. One would think it was now time to try some other trick; and ours is recommended (whatever this able philosopher may have been told to the contrary) by more than twelve years’ experience, wherein, among the great number of houses furnished with iron rods in North America, not one so guarded has been materially hurt with lightning, and several have evidently been preserved by their means; while a number of houses, churches, barns, ships, &c., in different places, unprovided with rods, have been struck and greatly damaged, demolished, or burnt. Probably the vestries of our English churches are not generally well acquainted with these facts; otherwise, since as good Protestants they have no faith in the blessing of bells, they would be less excusable in not providing this other security for their respective churches, and for the good people that may happen to be assembled in them during a tempest, especially as those buildings from their greater height, are more exposed to the stroke of lightning than our common dwellings.

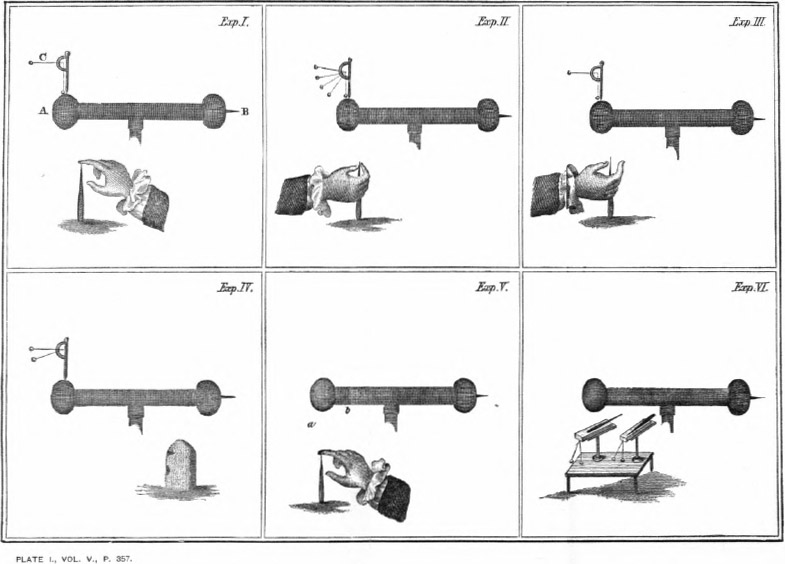

I have nothing new in the philosophical way to communicate to you, except what follows. When I Edition: current; Page: [12] was last year in Germany, I met with a singular kind of glass, being a tube about eight inches long, half an inch in diameter, with a hollow ball of near an inch diameter at one end, and one of an inch and a half at the other, hermetically sealed, and half filled with water. If one end is held in the hand, and the other a little elevated above the level, a constant succession of large bubbles proceeds from the end in the hand to the other end, making an appearance that puzzled me much, till I found that the space not filled with water was also free from air, and either filled with a subtile, invisible vapor continually rising from the water, and extremely rarefiable by the least heat at one end, and condensable again by the least coolness at the other; or it is the very fluid of fire itself, which parting from the hand pervades the glass, and by its expansive force depresses the water till it can pass between it and the glass, and escape to the other end, where it gets through the glass again into the air. I am rather inclined to the first opinion, but doubtful between the two.

An ingenious artist here, Mr. Nairne, mathematical instrument-maker, has made a number of them from mine, and improved them; for his are much more sensible than those I brought from Germany. I bored a very small hole through the wainscot in the seat of my window, through which a little cold air constantly entered, while the air in the room was kept warmer by fires daily made in it, being winter time. I Edition: current; Page: [13] placed one of his glasses, with the elevated end against this hole; and the bubbles from the other end, which was in a warmer situation, were continually passing day and night, to the no small surprise of even philosophical spectators. Each bubble discharged is larger than that from which it proceeds, and yet that is not diminished; and by adding itself to the bubble at the other end, the bubble is not increased, which seems very paradoxical.

When the balls at each end are made large, and the connecting tube very small, and bent at right angles, so that the balls, instead of being at the ends, are brought on the side of the tube, and the tube is held so that the balls are above it, the water will be depressed in that which is held in the hand, and rise in the other as a jet or fountain; when it is all in the other, it begins to boil, as it were, by the vapor passing up through it; and the instant it begins to boil, a sudden coldness is felt in the ball held; a curious experiment this, first observed and shown by Mr. Nairne. There is something in it similar to the old observation, I think mentioned by Aristotle, that the bottom of a boiling pot is not warm; and perhaps it may help to explain the fact; if indeed it be a fact.

When the water stands at an equal height in both these balls, and all at rest, if you wet one of the balls by means of a feather dipped in spirit, though that spirit is of the same temperament as to heat and cold with the water in the glasses, yet the cold occasioned by the evaporation of the spirit from the wetted ball will so condense the vapor over the water contained in that ball, as that the water of the other ball will be Edition: current; Page: [14] pressed up into it, followed by a succession of bubbles, till the spirit is all dried away. Perhaps the observations on these little instruments may suggest and be applied to some beneficial uses. It has been thought, that water reduced to vapor by heat was rarefied only fourteen thousand times, and on this principle our engines for raising water by fire are said to be constructed; but, if the vapor so much rarefied from water is capable of being itself still farther rarefied to a boundless degree, by the application of heat to the vessels or parts of vessels containing the vapor (as at first it is applied to those containing the water), perhaps a much greater power may be obtained, with little additional expense. Possibly, too, the power of easily moving water from one end to the other of a movable beam (suspended in the middle like a scale-beam) by a small degree of heat, may be applied advantageously to some other mechanical purposes.

The magic square and circle, I am told, have occasioned a good deal of puzzling among the mathematicians here; but no one has desired me to show him my method of disposing the numbers. It seems they wish rather to investigate it themselves. When I have the pleasure of seeing you, I will communicate it.

With singular esteem and respect, I am, dear Sir,

Your most obedient humble servant,

B. Franklin.

Edition: current; Page: [15]

CCCXXXVI: PETITION OF THE LETTER Z

From The Tatler, No. 1778.

To the Worshipful Isaac Bickerstaff, Esquire, Censor-General.

The petition of the letter Z, commonly called Ezzard, Zed, or Izard, most humbly showeth:

That your petitioner is of as high extraction, and has as good an estate, as any other letter of the Alphabet;

That there is therefore no reason why he should be treated as he is, with disrespect and indignity;

That he is not only actually placed at the tail of the Alphabet, when he had as much right as any other to be at the head; but it is by the injustice of his enemies totally excluded from the word WISE; and his place injuriously filled by a little hissing, crooked, serpentine, venomous letter, called S, when it must be evident to your worship, and to all the world, that W, I, S, E, do not spell Wize, but Wise.

Your petitioner therefore prays, that the Alphabet may by your censorial authority be reversed; and that in consideration of his long-suffering and patience he may be placed at the head of it; that S may be turned out of the word Wise, and the petitioner employed instead of him.

And your petitioner, as in duty bound, shall ever pray, &c., &c.

Mr. Bickerstaff, having examined the allegations of the above petition, judges and determines that Z be Edition: current; Page: [16] admonished to be content with his station, forbear reflections upon his brother letters, and remember his own small usefulness, and the little occasion there is for him in the Republic of Letters since S, whom he so despises, can so well serve instead of him.

CCCXXXVII

TO WILLIAM FRANKLIN

Since my last I have received yours of May 10th, dated at Amboy, which I shall answer particularly by next week’s packet. I purpose now to take notice of that part wherein you say it was reported at Philadelphia I was to be appointed to a certain office here, which my friends all wished, but you did not believe it for the reasons I had mentioned. Instead of my being appointed to a new office, there has been a motion made to deprive me of that I now hold, and, I believe, for the same reason, though that was not the reason given out, viz., my being too much of an American; but, as it came from Lord Sandwich, our new postmaster-general, who is of the Bedford party, and a friend of Mr. Grenville, I have no doubt that the reason he gave out, viz., my non-residence, was only the pretence, and that the other was the true reason; especially as it is the practice in many other instances to allow the non-residence of American officers, who spend their Edition: current; Page: [17] salaries here, provided care is taken that the business be done by deputy or otherwise.

The first notice I had of this was from my fast friend, Mr. Cooper, secretary of the treasury. He desired me, by a little note, to call upon him there, which I did, when he told me that the Duke of Grafton had mentioned to him some discourse of Lord Sandwich’s, as if the office suffered by my absence, and that it would be fit to appoint another, as I seemed constantly to reside in England; that Mr. Todd, secretary of the post-office, had also been with the Duke, talking to the same purpose, &c.; that the Duke wished him (Mr. Cooper) to mention this to me, and to say to me, at the same time, that, though my going to my post might remove the objection, yet, if I choose rather to reside in England, my merit was such in his opinion as to entitle me to something better here, and it should not be his fault if I was not well provided for. I told Mr. Cooper that, without having heard any exception had been taken to my residence here, I was really preparing to return home, and expected to be gone in a few weeks; that, however, I was extremely sensible of the Duke’s goodness in giving me this intimation, and very thankful for his favorable disposition towards me; that, having lived long in England, and contracted a friendship and affection for many persons here, it could not but be agreeable to me to remain among them some time longer, if not for the rest of my life; and that there was no nobleman to whom I could, from sincere respect for his great abilities and amiable qualities, so cordially attach myself, or to whom I Edition: current; Page: [18] should so willingly be obliged for the provision he mentioned, as to the Duke of Grafton, if his Grace should think I could, in any station where he might place me, be serviceable to him and to the public.

Mr. Cooper said he was very glad to hear I was still willing to remain in England, as it agreed so perfectly with his inclinations to keep me here; wished me to leave my name at the Duke of Grafton’s as soon as possible, and to be at the treasury again the next board day. I accordingly called at the Duke’s and left my card; and when I went next to the treasury, his Grace not being there, Mr. Cooper carried me to Lord North, chancellor of the exchequer, who said very obligingly, after talking of some American affairs, “I am told by Mr. Cooper that you are not unwilling to stay with us. I hope we shall find some way of making it worth your while.” I thanked his Lordship, and said I should stay with pleasure, if I could any ways be useful to government. He made me a compliment and I took my leave, Mr. Cooper carrying me away with him to his country-house at Richmond to dine and stay all night.

He then told me that Mr. Todd had been again at the Duke of Grafton’s, and that upon his (Mr. Cooper’s) speaking in my behalf, Mr. Todd had changed his style, and said I had, to be sure, a great deal of merit with the office, having by my good management regulated the posts in America so as greatly to increase the revenue; that he had had great satisfaction in corresponding with me while I was there, and he believed they never had a better officer, &c. The Thursday following, being the birthday, Edition: current; Page: [19] I met with Mr. Todd at court. He was very civil, took me with him in his coach to the King’s Arms in the city, where I had been invited to dine by Mr. Trevor, with the gentlemen of the post-office; we had a good deal of chat after dinner between us two, in which he told me Lord Sandwich (who was very sharp) had taken notice of my stay in England, and said, “If one could do the business why should there be two?” On my telling Mr. Todd that I was going home (which I still say to everybody, not knowing but that what is intimated above may fail of taking effect), he looked blank, and seemed disconcerted a little, which makes me think some friend of his was to have been vested with my place; but this is surmise only. We parted very good friends.

That day I received another note from Mr. Cooper, directing me to be at the Duke of Grafton’s next morning, whose porter had orders to let me in. I went accordingly, and was immediately admitted. But his Grace being then engaged in some unexpected business, with much condescension and politeness made that apology for his not discoursing with me then, but wished me to be at the treasury at twelve the next Tuesday. I went accordingly, when Mr. Cooper told me something had called the Duke into the country, and the board was put off, which was not known till it was too late to send me word; but was glad I was come, as he might then fix another day for me to go again with him into the country. The day fixed was Thursday. I returned yesterday; should have stayed till Monday, but for writing by Edition: current; Page: [20] these vessels. He assures me the Duke has it at heart to do something handsome for me. Sir John Pringle, who is anxious for my stay, says Mr. Cooper is the honestest man of a courtier that he ever knew, and he is persuaded they are in earnest to keep me.

The piece I wrote against smuggling, in the Chronicle of November last, and one in April, on the Laboring Poor, which you will find in the Gentleman’s Magazine for that month, have been lately shown by Mr. Cooper to the chancellor of the exchequer, and to the Duke, who have expressed themselves much pleased with them. I am to be again at the treasury on Tuesday next, by appointment of Mr. Cooper. Thus particular I have been, that you may judge of this affair.

For my own thoughts, I must tell you that, though I did not think fit to decline any favor so great a man expressed an inclination to do me, because at court if one shows an unwillingness to be obliged it is often construed as a mark of mental hostility, and one makes an enemy, yet, so great is my inclination to be at home and at rest, that I shall not be sorry if this business falls through, and I am suffered to retire with my old post; nor indeed very sorry if they take that from me, too, on account of my zeal for America, in which some of my friends have hinted to me that I have been too open. I shall soon be able, I hope, by the next packet to give you farther light. In the meantime, as no one but Sir John knows of the treaty, I talk daily of going in the August packet at farthest. And when the late Georgia appointment of me to be their agent is mentioned, Edition: current; Page: [21] as what may detain me, I say, I have yet received no letters from that Assembly acquainting me what their business may be; that I shall probably hear from them before that packet sails; that if it is extraordinary and of such a nature as to make my stay another winter necessary, I may possibly stay, because there would not be time for them to choose another; but if it is common business, I shall leave it with Mr. Jackson and proceed.

I do not, by the way, know how that appointment came about, having no acquaintance that I can recollect in that country. It has been mentioned in the papers some time; but I have only just now received a letter from Governor Wright, informing me that he had that day given his assent to it, and expressing his desire to correspond with me on all occasions, saying the Committee, as soon as they could get their papers ready, would write to me and acquaint me with their business.

We have lost Lord Clare from the Board of Trade. He took me home from court the Sunday before his removal, that I might dine with him, as he said, alone, and talk over American affairs. He seemed as attentive to them as if he was to continue ever so long. He gave me a great deal of flummery, saying that, though at my Examination I answered some of his questions a little pertly, yet he liked me from that Edition: current; Page: [22] day for the spirit I showed in defence of my country; and at parting, after we had drunk a bottle and a half of claret each, he hugged and kissed me, protesting he never in his life met with a man he was so much in love with. This I write for your amusement. You see by the nature of this whole letter that it is to yourself only. It may serve to prepare your mind for any event that shall happen.

If Mr. Grenville comes into power again, in any department respecting America, I must refuse to accept of any thing that may seem to put me in his power, because I apprehend a breach between the two countries; and that refusal might give offence. So that, you see, a turn of a die may make a great difference in our affairs. We may be either promoted or discarded; one or the other seems likely soon to be the case, but it is hard to divine which. I am myself grown so old as to feel much less than formerly the spur of ambition; and if it were not for the flattering expectation, that by being fixed here I might more effectually serve my country, I should certainly determine for retirement without a moment’s hesitation. I am, as ever, your affectionate father,

CCCXXXVIII

TO JOSEPH GALLOWAY

Since my last nothing material has occurred here relating to American affairs, except the Edition: current; Page: [23] removal of Lord Clare from the head of the Board of Trade to the treasury of Ireland, and the return of Lord Hillsborough to the Board of Trade as first commissioner, retaining the title and powers of secretary of state for the colonies. This change was very sudden and unexpected. My Lord Clare took me home from court to dine with him but two days before, saying he should be without other company and wanted to talk with me on sundry American businesses. We had accordingly a good deal of conversation on our affairs, in which he seemed to interest himself with all the attention that could be supposed in a minister who expected to continue in the management of them. This was on Sunday, and on the Tuesday following he was removed. Whether my Lord Hillsborough’s administration will be more stable than others have been for a long time, is quite uncertain; but as his inclinations are rather favorable towards us (so far as he thinks consistent with what he supposes the unquestionable rights of Britain), I cannot but wish it may continue, especially as these perpetual mutations prevent the progress of all business.

But another change is now talked of that gives me great uneasiness. Several of the Bedford party being now got in, it has been for some time apprehended that they would sooner or later draw their friend Mr. Grenville in after them. It is now said he is to be secretary of state, in the room of Lord Shelburne. If this should take place, or if in any other shape he comes again into power, I fear his sentiments of the Americans, and theirs of him, will occasion Edition: current; Page: [24] such clashings as may be attended with fatal consequences. The last accounts from your part of the world, of the combinations relating to commerce with this country, and resolutions concerning the duties here laid upon it, occasion much serious reflection; and it is thought the points in dispute between the two countries will not fail to come under the consideration of Parliament early in next session. Our friends wonder that I persist in my intention of returning this summer, alleging that I might be of much more service to my country here than I can be there, and wishing me by all means to stay the ensuing winter, as the presence of persons well acquainted with America, and of ability to represent these affairs in a proper light, will then be highly necessary. My private concerns, however, so much require my presence at home, that I have not yet suffered myself to be persuaded by their partial opinion of me.

The tumults and disorders, that prevailed here lately, have now pretty well subsided. Wilkes’ outlawry is reversed, but he is sentenced to twenty-two months imprisonment, and one thousand pounds fine, which his friends, who feared he would be pilloried, seem rather satisfied with. The importation of corn, a pretty good hay harvest, now near over, and the prospect of plenty from a fine crop of wheat, make the poor more patient, in hopes of an abatement in the price of provisions; so that, unless want of employment by the failure of American orders should distress them, they are like to be tolerably quiet.

I purpose writing to you again by the packet that goes next Saturday, and therefore now only add that Edition: current; Page: [25] I am, with sincere esteem, dear Sir, your most obedient and most humble servant,

CCCXXXIX

TO M. DUBOURG.

I greatly approve the epithet which you give, in your letter of the 8th of June, to the new method of treating the small-pox, which you call the tonic or bracing method; I will take occasion from it to mention a practice to which I have accustomed myself. You know the cold bath has long been in vogue here as a tonic; but the shock of the cold water has always appeared to me, generally speaking, as too violent, and I have found it much more agreeable to my constitution to bathe in another element, I mean cold air. With this view I rise almost every morning and sit in my chamber without any clothes whatever, half an hour or an hour, according to the season, either reading or writing. This practice is not in the least painful, but, on the contrary, agreeable; and, if I return to bed afterwards, before I dress myself, as sometimes happens, I make a supplement to my night’s rest of one or two hours of the most pleasing sleep that can be imagined. I find no ill consequences whatever resulting from it, and that at least it does not injure my health, if it does not in fact contribute much to its perservation. I shall therefore call it for the future a bracing or tonic bath.

Edition: current; Page: [26]

CCCXL

TO DUPONT DE NEMOURS

I received your obliging letter of the 10th May, with the most acceptable present of your Physiocratie, which I have read with great pleasure, and received from it a great deal of instruction. There is such a freedom from local and national prejudices and partialities, so much benevolence to mankind in general, so much goodness mixt with the wisdom, in the principles of your new philosophy, that I am perfectly charmed with them, and wish I could have stayed in Edition: current; Page: [27] France for some time, to have studied in your school, that I might by conversing with its founders have made myself quite a master of that philosophy. . . . I had, before I went into your country, seen some letters of yours to Dr. Templeman, that gave me a high opinion of the doctrines you are engaged in cultivating and of your personal talents and abilities, which made me greatly desirous of seeing you. Since I had not that good fortune, the next best thing is the advantage you are so good to offer me of your correspondence, which I shall ever highly value, and endeavor to cultivate with all the diligence I am capable of.

I am sorry to find that that wisdom which sees the welfare of the parts in the prosperity of the whole, seems yet not to be known in this country. . . . . We are so far from conceiving that what is best for mankind, or even for Europe in general, may be best for us, that we are even studying to establish and extend a separate interest of Britain, to the prejudice of even Ireland and our own colonies. . . . It is from your philosophy only that the maxims of a contrary and more happy conduct are to be drawn, which I therefore sincerely wish may grow and increase till it becomes the governing philosophy of the human species, as it must be that of superior beings in better worlds. I take the liberty of sending you a little fragment that has some tincture of it, which, on that account, I hope may be acceptable.

Be so good as to present my sincere respect to that venerable apostle, Dr. Quesnay, and to the illustrious Ami des Hommes (of whose civilities to me at Paris I Edition: current; Page: [28] retain a grateful remembrance), and believe me to be, with real and very great esteem, Sir,

Your obliged and most obedient humble servant,

CCCXLI

TO JOHN ALLEYNE, ESQ.

You desire, you say, my impartial thoughts on the subject of an early marriage, by way of answer to the numberless objections that have been made by numerous persons to your own. You may remember, when you consulted me on the occasion, that I thought youth on both sides to be no objection. Indeed, from the marriages that have fallen under my observation, I am rather inclined to think that early ones stand the best chance of happiness. The temper and habits of the young are not yet become so stiff and uncomplying as when more advanced in life; they form more easily to each other, and hence many occasions of disgust are removed. And if youth has less of that prudence which is necessary to manage a family, yet the parents and elder friends of young married persons are generally at hand to afford their advice, which amply supplies that defect; and by early marriage youth is sooner formed to regular and useful life; and possibly some of those accidents or connexions that might have injured the constitution, or reputation, or both, are thereby happily prevented.

Particular circumstances of particular persons may Edition: current; Page: [29] possibly sometimes make it prudent to delay entering into that state; but in general, when nature has rendered our bodies fit for it, the presumption is in nature’s favor, that she has not judged amiss in making us desire it. Late marriages are often attended, too, with this further inconvenience, that there is not the same chance that the parents shall live to see their offspring educated. “Late children,” says the Spanish proverb, “are early orphans.” A melancholy reflection to those whose case it may be! With us in America, marriages are generally in the morning of life; our children are therefore educated and settled in the world by noon; and thus, our business being done, we have an afternoon and evening of cheerful leisure to ourselves; such as our friend at present enjoys. By these early marriages we are blessed with more children; and from the mode among us, founded by nature, every mother suckling and nursing her own child, more of them are raised. Thence the swift progress of population among us, unparalleled in Europe.

In fine, I am glad you are married, and congratulate you most cordially upon it. You are now in the way of becoming a useful citizen; and you have escaped the unnatural state of celibacy for life, the fate of many here, who never intended it, but who, having too long postponed the change of their condition, find at length that it is too late to think of it, and so live all their lives in a situation that greatly lessens a man’s value. An odd volume of a set of books bears not the value of its proportion to the set. What think you of the odd half of a pair of scissors? It Edition: current; Page: [30] cannot well cut any thing; it may possibly serve to scrape a trencher.

Pray make my compliments and best wishes acceptable to your bride. I am old and heavy, or I should ere this have presented them in person. I shall make but small use of the old man’s privilege, that of giving advice to younger friends. Treat your wife always with respect; it will procure respect to you, not only from her, but from all that observe it. Never use a slighting expression to her, even in jest, for slights in jest, after frequent bandyings, are apt to end in angry earnest. Be studious in your profession, and you will be learned. Be industrious and frugal, and you will be rich. Be sober and temperate, and you will be healthy. Be in general virtuous, and you will be happy. At least you will, by such conduct, stand the best chance for such consequences. I pray God to bless you both; being ever your affectionate friend,

CCCXLII: A SCHEME FOR A NEW ALPHABET AND REFORMED MODE OF SPELLING

WITH REMARKS AND EXAMPLES CONCERNING THE SAME, AND AN ENQUIRY INTO ITS USES, IN A CORRESPONDENCE BETWEEN MISS STEVENSON AND DR. FRANKLIN, WRITTEN IN THE CHARACTERS OF THE ALPHABET

I hope I shall be forgiven for observing that even our present printed and written characters are fundamentally the same. The (Roman) printed one is Edition: current; Page: [31] certainly the neatest, simplest, and most legible of the two; but for the sake of ease and rapidity in our writing, it seems we there insert a number of joining or terminating strokes, substitute curves for angles, and give the letters a small inclination, to which rules even the letters a, g, r, and w, are easily reconcilable. This will cease to appear a remark of mere curiosity, if applied to the deciphering of foreign correspondence. But for this purpose I would add that the French in particular seem to treat the small up-stroke in the letters h, p, and c, as proceeding originally in an angle from the bottom of the down-stroke: they therefore begin it with a curve from the bottom, and keep it all the way distinct; hence forming their written r much like our written v. This last letter v, they again distinguish by a loop at the bottom; which loop they often place where we place an outward curve. The remarkable terminating s which they sometimes use, seems intended for our printed s begun from the bottom, but from corrupt writing inverted and put horizontally, instead of vertically. It is rather from bad writing than system that their n and m appear like u and w. I could go on to speak of the formation of written and printed capitals, but as this would be a work of mere curiosity, I leave it for the reader’s amusement.

Edition: current; Page: [32]

TABLE OF THE REFORMED ALPHABET

| SOUNDED, RESPECTIVELY, AS IN THE WORDS IN THE COLUMN BELOW |

| Characters |

|

| The six new letters are marked with an asterisk (*), to distinguish them and show how few new sounds are proposed. |

| o |

Old. |

| aw-phon |

John, folly; awl, ball. |

| a |

Man, can. |

| e |

Men, lend, name, lane. |

| i |

Did, sin, deed, seen. |

| u |

Tool, fool, rule. |

| uh-phon |

um, un; as in umbrage, unto, &c., and as in er. |

| h |

Hunter, happy, high. |

| g |

Give, gather. |

| k |

Keep, kick. |

| sh-phon |

(sh) Ship, wish. |

| ng-phon |

(ng) ing, repeating, among. |

| n |

End. |

| r |

Art. |

| t |

Teeth. |

| d |

Deed. |

| l |

Ell, tell. |

| s |

Essence. |

| z |

(ez) Wages. |

| th-phon |

(th) Think. |

| dh-phon |

(dh) Thy. |

| f |

Effect. |

| v |

Ever. |

| b |

Bees. |

| p |

Peep. |

| m |

Ember. |

Edition: current; Page: [33]

TABLE OF THE REFORMED ALPHABET

| Names of Letters as expressed in the reformed Sounds and Characters. |

MANNER OF PRONOUNCING THE SOUNDS |

| o |

The first VOWEL naturally, and deepest sound, requires only to open the mouth, and breathe through it. |

| aw-phon |

The next requiring the mouth opened a little more, or hollower. |

| a |

The next, a little more. |

| e |

The next requires the tongue to be a little more elevated. |

| i |

The next still more. |

| u |

The next requires the lips to be gathered up, leaving a small opening. |

| uh-phon |

The next a very short vowel, the sound of which we should express in our present letters thus, uh, a short, and not very strong aspiration. |

| huh |

A stronger or more forcible aspiration. |

| gi |

The first CONSONANT; being formed by the root of the tongue; this is the present hard g. |

| ki |

A kindred sound; a little more acute; to be used instead of the hard c. |

| ish |

A new letter wanted in our language; our sh, separately taken, not being proper elements of the sound. |

| ing |

A new letter wanted for the same reason.—These are formed back in the mouth. |

| en |

Formed more forward in the mouth, the tip of the tongue to the roof of the mouth. |

| r |

The same, the tip of the tongue a little loose or separate from the roof of the mouth, and vibrating. |

| ti |

The tip of the tongue more forward, touching, and then leaving the roof. |

| di |

The same, touching a little fuller. |

| el |

The same; touching just about the gums of the upper teeth. |

| es |

This sound is formed by the breath passing between the moist end of the tongue and the upper teeth. |

| ez |

The same, a little denser and duller. |

| eth-phon |

The tongue under, and a little behind, the upper teeth; touching them, but so as to let the breath pass between. |

| edh-phon |

The same; a little fuller. |

| ef |

Formed by the lower lip against the upper teeth. |

| ev |

The same; fuller and duller. |

| b |

The lips full together, and opened as the air passes out. |

| pi |

The same; but a thinner sound. |

| em |

The closing of the lips, while the e [here annexed] is sounding. |

Edition: current; Page: [34]

REMARKS ON THE ALPHABETICAL TABLE

| o { |

It is endeavoured to give the alphabet a more natural order; beginning first with the simple sounds formed by the breath, with none or very little help of tongue, teeth, and lips, and produced chiefly in the windpipe. |

| to { |

| y huh { |

| g k { |

Then coming forward to those formed by the roof of the tongue next to the windpipe. |

| r n { |

Then to those formed more forward, by the fore part of the tongue against the roof of the mouth. |

| t d { |

| l { |

Then those formed still more forward, in the mouth, by the tip of the tongue applied first to the roots of the upper teeth. |

| s z { |

| th-phon th { |

Then to those formed by the tip of the tongue applied to the ends or edges of the upper teeth. |

| dh-phon dh { |

| f { |

Then to those formed still more forward, by the under lip applied to the upper teeth. |

| v { |

| b { |

Then to those formed yet more forward, by the upper and under lip opening to let out the sounding breath. |

| p { |

| m { |

And lastly, ending with the shutting up of the mouth, or closing the lips, while any vowel is sounding. |

In this alphabet c is omitted as unnecessary; k supplying its hard sound, and s the soft; k also supplies Edition: current; Page: [35] well the place of q, and, with an s added, the place of x; q and x are therefore omitted. The vowel u, being sounded as oo, makes the w unnecessary. The y, where used simply, is supplied by i and, where as a diphthong, by two vowels; that letter is therefore omitted as useless. The jod j is also omitted, its sound being supplied by the new letter sh-phon, ish, which serves other purposes, assisting in the formation of other sounds; thus the sh-phon with a d before it gives the sound of the jod j and soft g, as in “James, January, giant, gentle,” “dsh-phoneems, dsh-phonanueri, dsh-phonyiant, dsh-phonentel”; with a t before it, it gives the sound of ch, as in “cherry, chip,” “tsh-phoneri, tsh-phonip”; and, with a z before it, the French sound of the jod j, as in “jamais,” “zsh-phoname.”

Thus the g has no longer two different sounds, which occasioned confusion, but is, as every letter ought to be, confined to one. The same is to be observed in all the letters, vowels, and consonants, that wherever they are met with, or in whatever company, their sound is always the same. It is also intended, that there be no superfluous letters used in spelling; that is, no letter that is not sounded; and this alphabet, by six new letters, provides that there be no distinct sounds in the language without letters to express them. As to the difference between short and long vowels, it is naturally expressed by a single vowel where short, a double one where long; as for “mend,” write “mend,” but for “remain’d,” write “remeen’d;” for “did,” write “did,” but for “deed,” write “diid,” &c.

What in our common alphabet is supposed the Edition: current; Page: [36] third vowel, i, as we sound it, is as a diphthong, consisting of two of our vowels joined; viz. uh-phon as sounded in “into,” and i in its true sound. Any one will be sensible of this, who sounds those two vowels uh-phon i quick after each other; the sound begins uh-phon and ends ii. The true sound of the i is that we now give to e in the words “deed, keep.” Though a single vowel appears to be put in the table for did and deed equally, yet in the remarks—above—the latter is made to require two i’s. Perhaps the same doubling of the vowel is meant for name and lane; for certainly name is not pronounced as nem, in the expression nem. con., corresponding to the sound in men. Some critics may probably think that these two sets of sounds are so distinct as to require different characters to express them: since in mem, pronounced affectedly for ma’am—madam—and corresponding in sound to men, the lips are kept close to the teeth, and perpendicular to each other; but in maim, corresponding in sound to name, the lips are placed poutingly and flat towards each other; a remark that might be applied with little variation to did and deed compared. As this is a subject I have never much examined, it becomes me only to add, that spelling may be considered as “an analysis of the operations of the organs of speech, where each separate letter has to represent a different movement”; and that among these organs of speech, we are to enumerate the epiglottis, and perhaps even the lungs themselves, not merely as furnishing air for sound, but as modifying the sound of that air both in inhaling and expelling it.

Edition: current; Page: [37]

EXAMPLES

- So huen suh-phonm endsh-phonel buh-phoni divuh-phonin kamand,

- Uidh-phon ruh-phonizing-phon tempests sh-phoneeks e gilti land,

- (Suh-phontsh-phon az aw-phonv leet or peel Britania past,)

- Kalm and siriin hi druh-phonivs dh-phoni fiuriuh-phons blast;

- And pliiz’d dh-phon’ aw-phonlmuh-phonitis aw-phonrduh-phonrs tu puh-phonrfaw-phonrm,

- Ruh-phonids in dh-phoni huuh-phonrluind and duh-phonirekts dh-phoni staw-phonrm,

- So dh-phoni piur limpid striim, huen faw-phonul uidh-phon steens

- aw-phonv ruh-phonsh-phoning-phon taw-phonrents and disending-phon reens,

- Uuh-phonrks itself kliir; and az it ruh-phonns rifuh-phonins;

- Til buh-phoni digriis, dh-phoni floting-phon miruh-phonr sh-phonuh-phonins,

- Riflekts iitsh-phon flaw-phonur dh-phonat aw-phonn its baw-phonrduh-phonr groz,

- And e nu hev’n in its feer buh-phonzuh-phonm sh-phonoz.

FROM MISS STEVENSON TO B. FRANKLIN

Kensing-phontuh-phonn,

26 Septembuh-phonr, 1768.

Diir Suh-phonr:—

uh-phoni hav transkruh-phonib’d iur alfabet, &c., huitsh-phon uh-phoni th-phonink muh-phonit bi aw-phonv suh-phonrvis tu dh-phonoz, hu uish-phon to akuuh-phonir an akiuret pronuh-phonnsiesh-phonuh-phonn, if dh-phonat kuld bi fiks’d; buh-phont uh-phoni si meni inkaw-phonnviiniensis, az uel az difikuh-phonltis dh-phonat uuld atend dh-phoni bring-phoning-phon iur letuh-phonrs and aw-phonrth-phonaw-phongrafi intu kaw-phonmuh-phonn ius. aw-phonaw-phonl aw-phonur etimaw-phonlodsh-phoniz uuld be law-phonst, kaw-phonnsikuentli ui kuld naw-phont asuh-phonrteen dh-phoni miining-phon aw-phonv meni uuh-phonrds; dh-phoni distinksh-phonuh-phonn, tu, bituiin uuh-phonrds aw-phonv difuh-phonrent miining-phon and similar saw-phonund uuld bi iusles, uh-phonnles ui living-phon ruh-phoniters puh-phonblish-phon nu iidish-phonuh-phonns. In sh-phonaw-phonrt uh-phoni biliiv ui muh-phonst let piipil spel aw-phonn in dh-phoneer old ue, and (as ui fuh-phonind it iisiiest) du dh-phoni Edition: current; Page: [38] seem aw-phonurselves. With ease and sincerity I can, in the old way, subscribe myself,

Dear Sir,

Your faithful and affectionate servant,

Dr. Franklin.

M. S.

ANSWER TO MISS STEVENSON

dh-phoni aw-phonbdsh-phoneksh-phonuh-phonn iu meek to rektifuh-phoniing-phon aw-phonur alfabet, “dh-phonat it uil bi atended uidh-phon inkaw-phonnviniensiz and difikuh-phonltiz,” iz e natural uuh-phonn; faw-phonr it aw-phonluaz aw-phonkyrz huen eni refaw-phonrmesh-phonuh-phonn is propozed; huedh-phonuh-phonr in rilidsh-phonuh-phonn, guh-phonvernment, law-phonz, and iven daw-phonun az lo az rods and huil karidsh-phoniz. dh-phoni tru kuestsh-phonuh-phonn dh-phonen, is naw-phont huedh-phonuh-phonr dh-phonaer uil bi no difikuh-phonltiz aw-phonr inkaw-phonnviniensiz, buh-phont huedh-phonuh-phonr dh-phoni difikuh-phonltiz mê naw-phont bi suh-phonrmaw-phonunted; and huedh-phonuh-phonr dh-phoni kaw-phonnviniensiz uil naw-phont, aw-phonn dh-phoni huol, bi grêtuh-phonr dh-phonan dh-phoni inkaw-phonnviniensiz. In dh-phonis kes, dh-phoni difikuh-phonltiz er onli in dh-phoni bigining-phon aw-phonv dh-phoni praktis; huen dh-phonê er uuh-phonns ovuh-phonrkuh-phonm, dh-phoni advantedsh-phonez er lasting-phon.—To uh-phonidh-phonuh-phonr iu aw-phonr mi, hu spel uel in dh-phoni prezent mod, uh-phoni imadsh-phonin dh-phoni difikuh-phonlti aw-phonv tsh-phonendsh-phoning-phon dh-phonat mod faw-phonr dh-phoni nu, iz naw-phont so grêt, buh-phont dh-phonat ui muh-phonit puh-phonrfektli git ovuh-phonr it in a uiik’s ruh-phoniting-phon.—Az to dh-phonoz hu du naw-phont spel uel, if dh-phoni tu difikuh-phonltiz er kuh-phonmpêrd, viz., dh-phonat aw-phonv titsh-phoning-phon dh-phonem tru speling-phon in dh-phoni prezent mod, and dh-phonat aw-phonv titsh-phoning-phon dh-phonem dh-phoni nu alfabet and dh-phoni nu speling-phon akaw-phonrding-phon to it, uh-phoni am kaw-phonnfident dh-phonat dh-phoni latuh-phonr uuld bi byi far dh-phoni liist. dh-phonê natuh-phonrali faw-phonl into dh-phoni nu meth-phonuh-phond alrehdi, az muh-phontsh-phon az dh-phoni imperfeksh-phonuh-phonn aw-phonv dh-phonêr alfabet uil admit aw-phonv; dh-phonêr prezent bad speling-phon iz onli bad, bikaw-phonz kaw-phonntreri to dh-phoni prezent bad ruls; uh-phonnduh-phonr dh-phoni nu ruls it uuld bi gud.—dh-phoni difikuh-phonlti aw-phonv luh-phonrning-phon to spel uel in dh-phoni old uê iz so grêt, dh-phonat fiu atên it; th-phonauzands Edition: current; Page: [39] and th-phonaw-phonuzands ruh-phoniting-phon aw-phonn to old edsh-phon, uidh-phonaw-phonut ever biing-phon ebil to akuuh-phonir it. ’Tiz, bisuh-phonidz, e difikuh-phonlti kaw-phonntinuali inkriising-phon, az dh-phoni saw-phonund graduali veriz mor and mor fraw-phonm dh-phoni speling-phon; and to faw-phonrenuh-phonrs it mêks dh-phoni luh-phonrning-phon to pronaw-phonuns aw-phonur lang-phonuedsh-phon, az riten in aw-phonur buks, almost impaw-phonsibil.

Naw-phonu az to “dh-phoni inkaw-phonnviniensiz” iu mensh-phonuh-phonn.—dh-phoni fuh-phonrst iz, dh-phonat “aw-phonaw-phonl aw-phonur etimaw-phonlodsh-phoniz uuld bi law-phonst, kaw-phonnsikuentli ui kuld naw-phont asuh-phonrteen dh-phoni miining-phon aw-phonv meni uuh-phonrds.”—Etimaw-phonlodsh-phoniz er at prezent veri uh-phonnsuh-phonrteen; buh-phont suh-phontsh-phon az dh-phonê er, dh-phoni old buks uuld stil prizuh-phonrv dh-phonem, and etimaw-phonlodsh-phonists uuld fuh-phonind dh-phonem. Uuh-phonrds in dh-phoni kors aw-phonv tuh-phonim, tsh-phonendsh-phon dh-phoner miining-phons, az uel az dh-phoner speling-phon and pronuh-phonnsiesh-phonuh-phonn; and ui du naw-phont luk to etimaw-phonlodsh-phoni faw-phonr dh-phoner prezent miining-phons. If uh-phoni sh-phonuld kaw-phonl e man e neev and e vilen, hi uuld hardli bi satisfuh-phonid uidh-phon muh-phoni teling-phon him, dh-phonat uuh-phonn aw-phonv dh-phoni uuh-phonrds oridsh-phoninali signifuh-phonid onli e lad aw-phonr suh-phonrvant; and dh-phoni uh-phondh-phonuh-phonr, an uh-phonnduh-phonr plaw-phonuman, aw-phonr dh-phoni inhabitant aw-phonv e viledsh-phon. It iz fraw-phonm prezent iusedsh-phon onli, dh-phoni miining-phon aw-phonv uuh-phonrds iz to bi dituh-phonrmined.

Iur sekuh-phonnd inkaw-phonnviniens iz, dh-phonat “dh-phoni distinksh-phonyn bituiin uuh-phonrds aw-phonv difuh-phonrent miining-phon and similar saw-phonund Edition: current; Page: [40] uuld bi distraw-phonuh-phonid.”—dh-phonat distinksh-phonuh-phonn iz aw-phonlreadi distraw-phonuh-phonid in pronaw-phonunsing-phon dh-phonem; and ui riluh-phoni aw-phonn dh-phoni sens alon aw-phonv dh-phoni sentens to asuh-phonrteen, huitsh-phon aw-phonv dh-phoni several uuh-phonrds, similar in saw-phonund, ui intend. If dh-phonis iz suh-phonfish-phonent in dh-phoni rapidtti aw-phonv diskors, it uil bi mutsh-phon mor so in riten sentenses, huitsh-phon mê bi red lezsh-phonurli, and atended to mor partikularli in kes aw-phonv difikuh-phonlti, dh-phonan ui kan atend to e paft sentens, huuh-phonil e spikuh-phonr iz huh-phonruh-phoniing-phon uh-phons alaw-phonng-phon uidh-phon nu uuh-phonns.

Iur th-phonuh-phonrd inkaw-phonnviniens iz, dh-phonat “aw-phonaw-phonl dh-phoni buks alredi riten uuld bi iusles.”—dh-phonis inkaw-phonnviniens uuld onli kuh-phonm aw-phonn graduali, in e kors aw-phonv edsh-phones. Iu and uh-phoni, and uh-phondh-phonuh-phonr naw-phonu living-phon riduh-phonrs, uuld hardli faw-phonrget dh-phoni ius aw-phonv dh-phonem. Piipil uuld long-phon luh-phonrn to riid dh-phoni old ruh-phoniting-phon, dh-phono dh-phonê praktist dh-phoni nu.—And dh-phoni inkaw-phonnviniens iz naw-phont greter dh-phonan huat hes aktuali hapend in e similar kes, in Iteli. Faw-phonrmerli its inhabitants aw-phonaw-phonl spok and rot Latin; az dh-phoni lang-phonuedsh-phon tsh-phonendsh-phond, dh-phoni speling-phon faw-phonlo’d it. It iz tru dh-phonat, at prezent, e miir uh-phonnlern’d Italien kanaw-phont riid dh-phoni Latin buks; dh-phono dh-phonê er stil red and uh-phonnduh-phonrstud buh-phoni meni. Buh-phont, if dh-phoni speling-phon had nevuh-phonr bin tsh-phonendsh-phoned, hi uuld naw-phonu hev faw-phonund it muh-phontsh-phon mor difikuh-phonlt to riid and ruh-phonit hiz on lang-phonuadsh-phon; faw-phonr riten uuh-phonrds uuld heve had no rilêsh-phonuh-phonn to saw-phonunds, dh-phonê uuld onli hev stud faw-phonr dh-phoning-phons; so dh-phonat if hi uuld ekspres in ruh-phoniting-phon dh-phoni uh-phonidia hi hez huen hi saw-phonunds dh-phoni uuh-phonrd Vescovo, hi muh-phonst iuz dh-phoni letterz Episcopus.—In sh-phonaw-phonrt, huatever dh-phoni difikuh-phonltiz and inkaw-phonnviniensiz naw-phonu er, dh-phonê uil bi mor iizili suh-phonrmaw-phonunted naw-phonu, dh-phonan hiraftuh-phonr; and suh-phonm tuh-phonim aw-phonr uh-phondh-phonuh-phonr, it muh-phonst bi duh-phonn; aw-phonr aw-phonur ruh-phoniting-phon uil bikuh-phonm dh-phoni sêm uidh-phon dh-phoni Tsh-phonuh-phoniniiz, az to dh-phoni difikuh-phonlti Edition: current; Page: [41] aw-phonv luh-phonrning-phon and iuzing it. And it uuld alredi hev bin suh-phontsh-phon, if ui had kaw-phonntinud dh-phoni Saksuh-phonn speling-phon and ruh-phoniting-phon, iuzed buh-phoni our forfadh-phoners.

uh-phoni am, muh-phoni diir frind, iurs afeksh-phonuh-phonnetli,

B. Franklin.

Luh-phonnduh-phonn,

Kreven-striit, Sept. 28, 1768.

CCCXLIII

TO MRS. DEBORAH FRANKLIN

It feels very strange to have ships and packets come in, and no letters from you. But I do not complain of it, because I know the reason is, my having written to you that I was coming home. That you may not have the same disagreeable sensation, I write this line, though I have written largely by the late ship, and therefore have little left to say. I have lately been in the country to spend a few days at friends’ houses, and to breathe a little fresh air. I have made no very long journey this summer as usual, finding myself in very good health, a greater share of which I believe few enjoy at my time of life; but we are not to expect it will be always sunshine. Cousin Folger, who is just arrived from Boston, tells me he saw our son and daughter Bache at that place, and that they were going farther, being very well, which I was glad to hear. My love to them and all friends, from your ever affectionate husband.

Edition: current; Page: [42]

CCCXLIV

FROM JOSEPH GALLOWAY TO B. FRANKLIN

Philadelphia,

17 October, 1768

.

Dear Sir:—

I have for some time omitted to write to you, from an apprehension that my letters might not meet you in England. But finding by your favor of August 13th, now before me, that you have altered your intention of seeing America this fall, I again resume my pen.

The new Assembly of this province, chiefly composed of the old members, adjourned on Saturday last to the 2d of January. They have again appointed yourself and Mr. Jackson their agents, to whom I enclose a letter from the Committee of Correspondence. You will perceive by it that they have a sixth time renewed the instructions relating to a change of government, every member now approving of the measure, save the Chief-Justice. So that you are not to judge of the desire of the House to have the measure accomplished by the brevity of the letter, which was occasioned by the shortness of their sitting, and the fulness of the instructions of former Houses, which rendered much on the subject unnecessary.

I am much obliged by the particular account of the situation in which this matter stands. No part of it, which you wish to be concealed, shall transpire. You really judge right; should the petitions be rejected or neglected, the crown will never have the like request made by the people, nor such another opportunity of resuming one of the most beneficial governments in Edition: current; Page: [43] America. Their own welfare will oblige them to court the proprietary favor; and, should they continue to gratify the people, by the lenient measures adopted during the last year, they will place all their confidence in them, and lose all ideas of loyalty or affection to the person, where alone they ought to be fixed. The revenues of our Proprietaries are immense; not much short, at this time, of one hundred thousand pounds per annum. And, had they as much policy as money, they might easily find means with their vast treasure so to endear themselves to the people, as to prevail on them to forget all duty and affection to others. As to the peoples paying, it never can be done, nor is it just they should; nor would they ever agree to establish fixed salaries on governors, for the reasons you have mentioned.

It is truly discouraging to a people, who wish well to the mother country, and by their dutiful behaviour during these times of American confusion have recommended themselves to the crown, to have an application so honorable and beneficial to the latter so much neglected. Would the ministry coolly attend to the matter, it would certainly be otherwise. However, I am convinced, should the people once despair of the change, either the greatest confusion, or the consequence you have pointed out, will assuredly ensue.

Two regiments, commanded by Colonel Dalrymple, are arrived at Boston, and we learn the town is providing quarters for them; so that I hope the mischiefs, which some have thought would attend that measure, will not follow. Great pains have been Edition: current; Page: [44] taken in this city by some hot-headed, indiscreet men, to raise a spirit of violence against the late act of Parliament; but the design was crushed in its beginning by our friends so effectually, that I think we shall not soon have it renewed.

Your continuance in London this winter gives the Assembly much satisfaction, as there is a great probability that American affairs will come before the present Parliament, and they have the fullest confidence in you. My good friend, Governor Franklin, is now at Fort Stanwix with Sir William Johnson, where a treaty is holding respecting a general boundary. I have had a letter from him since his arrival there, and he is well. I write in much hurry, which will apologize for incorrectness. Believe me, my dear friend, with the most perfect esteem, &c.,

CCCXLV

TO MISS MARY STEVENSON

I see very clearly the unhappiness of your situation, and that it does not arise from any fault in you. I pity you most sincerely. I should not, however, have thought of giving you advice on this occasion, if you had not requested it, believing, as I do, that your own good sense is more than sufficient to direct you in every point of duty to others and yourself. If, then, I should advise you to any thing that may Edition: current; Page: [45] be contrary to your own opinion, do not imagine that I shall condemn you if you do not follow such advice. I shall only think that, from a better acquaintance with circumstances, you form a better judgment of what is fit for you to do.

Now, I conceive with you, that ——, both from her affection to you, and from the long habit of having you with her, would really be miserable without you. Her temper, perhaps, was never of the best; and, when that is the case, age seldom mends it. Much of her unhappiness must arise from thence; and since wrong turns of mind, when confirmed by time, are almost as little in our power to cure as those of the body, I think with you that her case is a compassionable one.

If she had, through her own imprudence, brought on herself any grievous sickness, I know you would think it your duty to attend and nurse her with filial tenderness, even were your own health to be endangered by it. Your apprehension, therefore, is right, that it may be your duty to live with her, though inconsistent with your happiness and your interest; but this can only mean present interest and present happiness; for I think your future, greater, and more lasting interest and happiness will arise from the reflection that you have done your duty, and from the high rank you will ever hold in the esteem of all that know you, for having persevered in doing that duty under so many and great discouragements.

My advice, then, must be, that you return to her as soon as the time proposed for your visit is expired; and that you continue, by every means in your power, Edition: current; Page: [46] to make the remainder of her days as comfortable to her as possible. Invent amusements for her; be pleased when she accepts of them, and patient when she perhaps peevishly rejects them. I know this is hard, but I think you are equal to it; not from any servility of temper, but from abundant goodness. In the meantime, all your friends, sensible of your present uncomfortable situation, should endeavour to ease your burden, by acting in concert with you, and to give her as many opportunities as possible of enjoying the pleasures of society, for your sake.

Nothing is more apt to sour the temper of aged people, than the apprehension that they are neglected; and they are extremely apt to entertain such suspicions. It was therefore that I proposed asking her to be of our late party; but, your mother disliking it, the motion was dropped, as some others have been, by my too great easiness, contrary to my judgment. Not but that I was sensible her being with us might have lessened our pleasure, but I hoped it might have prevented you some pain.

In fine, nothing can contribute to true happiness, that is inconsistent with duty; nor can a course of action, conformable to it, be finally without an ample reward. For God governs; and he is good. I pray him to direct you; and, indeed, you will never be without his direction, if you humbly ask it, and show yourself always ready to obey it. Farewell, my dear friend, and believe me ever sincerely and affectionately yours,

Edition: current; Page: [47]

CCCXLVI

TO A FRIEND

London,

28 November, 1768

.

Dear Sir:—

I received your obliging favor of the 12th instant. Your sentiments of the importance of the present dispute between Great Britain and the colonies appear to me extremely just. There is nothing I wish for more than to see it amicably and equitably settled.

But Providence will bring about its own ends by its own means; and if it intends the downfall of a nation, that nation will be so blinded by its pride and other passions as not to see its danger, or how its fall may be prevented.

Being born and bred in one of the countries, and having lived long and made many agreeable connexions of friendship in the other, I wish all prosperity to both; but I have talked and written so much and so long on the subject, that my acquaintance are weary of hearing, and the public of reading, any more of it, which begins to make me weary of talking and writing; especially as I do not find that I have gained any point in either country, except that of rendering myself suspected by my impartiality; —in England, of being too much an American, and in America, of being too much an Englishman. Your opinion, however, weighs with me, and encourages me to try one effort more, in a full though concise statement of facts, accompanied with arguments drawn from those facts; to be published about the meeting of Parliament, Edition: current; Page: [48] after the holidays. If any good may be done I shall rejoice; but at present I almost despair.

Have you ever seen the barometer so low as of late? The 22d instant mine was at 28.41, and yet the weather fine and fair. With sincere esteem, I am, dear friend, yours affectionately,

CCCXLVII

TO MRS. DEBORAH FRANKLIN

London,

21 December, 1768

.

My Dear Child:—

I wonder to hear that my friends were backward in bringing you my letters when they arrived, and think it must be a mere imagination of yours, the effect of some melancholy humor you happened then to be in. I condole with you sincerely on poor Debby’s account, and I hope she got well to her husband with her two children.

You say in yours of October 18th, “For me to give you any uneasiness about your affairs here, would be of no service, and I shall not at this time enter on it.” I am made by this to apprehend that something is amiss, and perhaps have more uneasiness from the uncertainty than I should have had if you had told me what it was. I wish, therefore, you would be explicit in your next. I rejoice that my good old friend, Mr. Coleman, is got safe home and continues well.

Remember me respectfully to Mr. Rhoads, Mr. Wharton, Mr. Roberts, Mr. and Mrs. Duffield, neighbour Edition: current; Page: [49] Thomson, Dr. and Mrs. Redman, Mrs. Hopkinson, Mr. Duché, Dr. Morgan, Mr. Hopkinson, and all the other friends you have from time to time mentioned as inquiring after me. As you ask me, I can assure you that I do really intend, God willing, to return in the summer, and that as soon as possible after settling matters with Mr. Foxcroft, whom I expect in April or May. I am glad that you find so much reason to be satisfied with Mr. Bache. I hope all will prove for the best. Captain Falconer has been arrived at Plymouth some time, but, the winds being contrary, could get no farther; so I have not yet received the apples, meal, &c., and fear they will be spoiled. I send with this some of the new kind of oats much admired here to make oatmeal of, and for other uses, as being free from husks; and some Swiss barley, six rows to an ear. Perhaps our friends may like to try them, and you may distribute the seed among them. Give some to Mr. Roberts, Mr. Rhoads, Mr. Thomson, Mr. Bartram, our son, and others.

I hope the cold you complain of in two of your letters went off without any ill consequences. We are, as you observe, blest with a great share of health, considering our years, now sixty-three. For my own part, I think of late that my constitution rather mends. I have had but one touch of the gout, and that a light one, since I left you. It was just after my arrival here, so that this is the fourth winter I have been free. Walking a great deal tires me less than it used to do. I feel stronger and more active. Yet I would not have you think that I fancy I shall Edition: current; Page: [50] grow young again. I know that men of my bulk often fail suddenly. I know that, according to the course of nature, I cannot at most continue much longer, and that the living even of another day is uncertain. I therefore now form no schemes but such as are of immediate execution, indulging myself in no future prospect except one, that of returning to Philadelphia, there to spend the evening of life with my friends and family.

Mr. and Mrs. Strahan, and Mr. and Mrs. West, when I last saw them, desired to be kindly remembered to you. Mrs. Stevenson and our Polly send their love. Mr. Coombe, who seems a very agreeable young man, lodges with us for the present. Adieu, my dear Debby. I am, as ever, your affectionate husband,

CCCXLVIII

TO MICHAEL COLLINSON, ESQ.

[Date uncertain.]

Dear Sir:—

Understanding that on account of our dear departed friend, Mr. Peter Collinson, is intended Edition: current; Page: [51] to be given to the public, I cannot omit expressing my approbation of the design. The characters of good men are exemplary, and often stimulate the well-disposed to an imitation, beneficial to mankind and honorable to themselves. And as you may be unacquainted with the following instance of his zeal and usefulness in promoting knowledge, which fell within my observation, I take the liberty of informing you that in 1730, a subscription library being set on foot at Philadelphia, he encouraged the design by making several very valuable presents to it, and procuring others from his friends; and as the library company had a considerable sum arising annually to be laid out in books, and needed a judicious friend in London to transact the business for them, he voluntarily and cheerfully undertook that service, and executed it for more than thirty years successively, assisting in the choice of books, and taking the whole care of collecting and shipping them, without ever charging or accepting any consideration for his trouble. The success of this library (greatly owing to his kind countenance and good advice) encouraged the erecting others in different places on the same plan; and it is supposed there are now upwards of thirty subsisting in the several colonies, which have contributed greatly to the spreading of useful knowledge in that part of the world; the books he recommended being all of that kind, and the catalogue of Edition: current; Page: [52] the first library being much respected and followed by those libraries that succeeded.

During the same time he transmitted to the directors of the library the earliest account of every new European improvement in agriculture and the arts, and every philosophical discovery; among which, in 1745, he sent over an account of the new German experiments in electricity, together with a glass tube, and some directions for using it, so as to repeat those experiments. This was the first notice I had of that curious subject, which I afterwards prosecuted with some diligence, being encouraged by the friendly reception he gave to the letters I wrote to him upon it. Please to accept this small testimony of mine to his memory, for which I shall ever have the utmost respect; and believe me, with sincere esteem, dear Sir, your most humble servant,

CCCXLIX

TO LORD KAMES

It is always a great pleasure to me to hear from you, and would be a much greater to be with you, to converse with you on the subjects you mention, or any other. Possibly I may one day enjoy that pleasure. In the meantime we may use the privilege that the knowledge of letters affords us, of conversing at a distance by the pen.

Edition: current; Page: [53]

I am glad to find you are turning your thoughts to political subjects, and particularly to those of money, taxes, manufactures, and commerce. The world is yet much in the dark on these important points; and many mischievous mistakes are continually made in the management of them. Most of our acts of Parliament for regulating them are, in my opinion, little better than political blunders, owing to the ignorance of science or to the designs of crafty men, who mislead the legislature, proposing something under the specious appearance of public good, while the real aim is to sacrifice that to their private interest. I hope a good deal of light may be thrown on these subjects by your sagacity and acuteness. I only wish I could first have engaged you in discussing the weighty points in dispute between Britain and the colonies. But the long letter I wrote you for that purpose, in February or March, 1767, perhaps never reached your hand, for I have not yet had a word from you in answer to it.

The act you inquire about had its rise thus: During the war Virginia issued great sums of paper money for the payment of their troops to be sunk in a number of years by taxes. The British merchants trading thither received these bills in payment for their goods, purchasing tobacco with them to send home. The crop of tobacco one or two years falling short, the factors, who were desirous of making a speedy remittance, sought to pay, with the paper money, bills of exchange. The number of bidders for these bills raised the price of them thirty per cent. Edition: current; Page: [54] above par. This was deemed so much loss to the purchasers, and supposed to arise from a depreciation of the paper money. The merchants, on this supposition, founded a complaint against that currency to the Board of Trade. Lord Hillsborough, then at the head of that Board, took up the matter strongly, and drew a report, which was presented to the King in Council, against all paper currency in the colonies. And, though there was no complaint against it from any merchants but those trading to Virginia, all those trading to the other colonies being satisfied with its operation, yet the ministry proposed and the Parliament came into the making a general act, forbidding all future emissions of paper money, that should be a legal tender in any colony whatever.

The Virginia merchants have since had the mortification to find that, if they had kept the paper money a year or two, the above-mentioned loss would have been avoided; for as soon as tobacco became more plenty, and of course bills of exchange also, the exchange fell as much as it before had risen. I was in America when the act passed. On my return to England I got the merchants trading to New York, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, &c., to meet, to consider, and join in an application to have the restraining act repealed. To prevent this application, a copy was put into the merchants’ hands of Lord Hillsborough’s report, by which it was supposed they might be convinced that such an application would be wrong. They desired my sentiments on it, which I gave in the paper I send you enclosed. I have no copy by me of the report itself; but in my answer Edition: current; Page: [55] you will see a faithful abridgment of all the arguments or reasons it contained. Lord Hillsborough has read my answer, but says he is not convinced by it, and adheres to his former opinion. We know nothing can be done in Parliament; that the minister is absolutely against, and therefore we let that point rest for the present. And as I think a scarcity of money will work with our other present motives for lessening our fond extravagance in the use of the superfluous manufactures of this country, which unkindly grudges us the enjoyment of common rights, and will tend to lead us naturally into industry and frugality, I am grown more indifferent about the repeal of the act, and if my countrymen will be advised by me, we shall never ask it again.