(A.) Bibliography of Ricardo’s Works

This list includes the writings of Ricardo which were published separately. Apart from these there are only the contributions to the Morning Chronicle of 1809 and 1810, the article ‘Funding System’ in 1820, and after his death a few scattered letters which were printed at various times. References to these will be found where the items appear in the present edition.

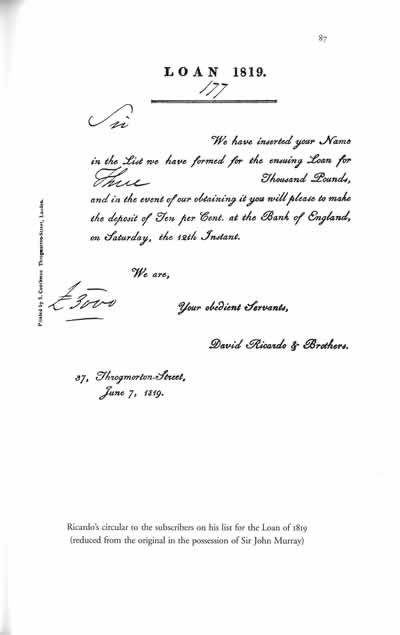

To the bibliographical descriptions have been added some items of information that seemed of interest, such as the numbers of copies printed according to the publishers’ records. Since there was no official day of publication in Ricardo’s time (Murray’s ‘Publications date book’ begins only in 1840), the date on which the original editions appeared can only be inferred approximately, chiefly from advertisements in the newspapers; such dates, with the evidence on which they are based, have been quoted in the introduction to each work in the previous volumes. Facsimiles of title-pages have been included in vols. I-IV. The size is octavo, unless otherwise stated.

The bibliography closes in 1932, the year in which most of the material for it was collected. It has not seemed reasonable to trouble again so many people in so many places in order to extend it beyond that date. It may be mentioned, however, that the following foreign editions of the Principles have since come to the notice of the editor: a new French translation by C. Debyser (in 2 vols., Paris, A. Costes, 1933–34), a new Italian translation by R. Fubini (with appended new translations of four of the pamphlets byA. Campolongo, Turin, U.T.E.T., 1948) and for the first time a Spanish translation by E. Pepe (Buenos Aires, Claridad, 1937) and a Greek translation by N. P. Constantinides (Athens, 1938).

The absence till recently of a Spanish edition is curious, the more so since L. Cossa in one of his bibliographical essays (Supplement to Giornale degli Economisti, August 1895) lists a Spanish translation of Ricardo’s Principles by Juan Antonio Seoane as published at Madrid in 1848. No copy of such a translation has been traced, and its existence is extremely doubtful. Edition: current; Page: [356]Perhaps there had been some preliminary announcement, but the project was submerged by the events of that year.

Foreign editions have been grouped by countries; the American editions being placed after the English and the others following in the chronological order of their first translation. The list of Russian translations is mainly based on that given in the 1929 Moscow edition of the Principles.

Information on their respective editions has been kindly supplied by Sir John Murray, Messrs G. Bell and Sons, Messrs J. M. Dent and Sons and The Macmillan Company. Help in tracing foreign editions has to be acknowledged from: Professor Jacob Viner, Professor Fritz Machlup, Dr P. N. Rosenstein-Rodan, Dr Oskar Lange, Professor Harald Westergaard, Mr N. J. Kohanovsky of Riga, Professor Shinzo Koizumi of Keio University, Tokyo, Professor Tsuneo Hori of the Osaka University of Commerce, Professor T. Uyeda of the Tokyo University of Commerce, Mr M. Y. Chao of Yenching University, Peking, Mr T. C. Li of Shanghai and Mr P. C. Ghosh of the University of Calcutta.

[1a] The High Price of Bullion, A Proof of the Depreciation of Bank Notes. [tapering rule] By David Ricardo. [double rule]

London: Printed for John Murray, 32, Fleet-street; and sold by every other Bookseller in Town and Country. [rule] 1810.

Collation: [A]2 B-D8; 26 leaves.

Contents: [A]1 title-page; [A]1v advertisement Just Published, The Quarterly Review, No. IV [contents given] and at the bottom imprint Harding and Wright, Printers, St. John’s-square, London; [A]2–2v (pp. [iii]-iv) Introduction; B1-D8v (pp. [1]–48) text, and at the bottom of D8v imprint Harding and Wright, Printers, St. John’s-Square, London.

Note: The price is given as 2s. in the advt. in The Times 3 Jan. 1810.

Edition: current; Page: [357]

[1b] The High Price of Bullion, A Proof of the Depreciation of Bank Notes. [tapering rule] Second Edition, Corrected. [tapering rule] By David Ricardo. [double rule]

London: Printed for John Murray, 32, Fleet-street. [rule] 1810.

Collation: [*]2 [A]2 B-D8; 28 leaves. [*]2 is folded round the rest of the pamphlet so as to enclose it.

Contents: [*]1 half-title Second Edition. [rule] Ricardo on Bullion and Bank notes. [double rule] Price Two Shillings.; [*]1v imprint Harding and Whight [sic], Printers, St. John’s-Square, London.; [A]1 title-page; [A]1v blank; [A]2–2v (pp. [iii]-iv) Introduction; B1-D8v (pp. [1]–48) text; [*]2 blank; [*]2v advertisement Just published, The Quarterly Review, No. IV [contents given], and at the bottom imprint Harding and Wright, Printers, St. John’s-square, London.

[1c] The High Price of Bullion, A Proof of the Depreciation of Bank Notes. [tapering rule] Third Edition, with Additions. [tapering rule] By David Ricardo. [double rule]

London: Printed by Harding & Wright, St. John’s-square, for John Murray, 32, Fleet-street. [rule] 1810.

Collation: [*]2 [A]2 B-D8 E4; 32 leaves. [*]2 is folded round the rest of the pamphlet so as to enclose it.

Contents: [*]1 half-title Third Edition, with Additions. [tapering rule] Ricardo on Bullion and Bank Notes. [double rule] Price Two Shillings and Sixpence. [*]1v blank; [A]1 title-page;[A]1v blank; [A]2–2v (pp. [iii]-iv) Introduction; B1-E4v (pp. [1]–56) text; [*]2 blank; [*]2v advertisement Lately published by J. Murray, 32, Fleet-street. [list of six titles, the first being The Quarterly Review, No. IV., with note No. V. will be published in March]; at the bottom of [*]2v imprint Harding and Wright, Printers, St. John’s Square, London.

[1d] The High Price of Bullion, A Proof of the Depreciation of Bank Notes. [tapering rule] By David Ricardo. [tapering rule] The Fourth Edition, Corrected. To which is added, An Appendix, containing Observations Edition: current; Page: [358]on some passages in an Article in the Edinburgh Review, on the Depreciation of Paper Currency; also Suggestions for securing to the Public a Currency as Invariable as Gold, with a very moderate Supply of that Metal. [double rule]

London: Printed for John Murray, 32, Fleet-street; William Blackwood, Edinburgh; and M. N. Mahon, Dublin. [rule] 1811.

Collation: [A]2 B-G8 H2; 52 leaves.

Contents: [A]1 half-title The High Price of Bullion, A Proof of the Depreciation of Bank Notes. [double rule] 4s. [rule] T. Davison, Lombard-street, Whitefriars, London. [A]1v blank;[A]2 title-page; [A]2v blank; B1-F1v (pp. [1]–66) text; F2-H1 (pp. [67]–97) Appendix [printed in smaller type]; H1v blank; H2–2v advertisement Books Published by John Murray, Fleet-street. [list of twelve titles including Ricardo’s Reply to Bosanquet and Huskisson’s Depreciation of our Currency, 7th ed.] and at bottom of H2v imprint T. Davison, Lombard-street, Whitefriars, London.

Notes: In some newspaper advertisements the price is given as 3s. 6d. (Monthly Literary Advertiser, 10 April, Morning Chronicle, 27 April 1811); but 4s., as stated on the pamphlet, seems more likely to be correct.

In Murray’s ledgers there is no record of the numbers printed of the first three eds.; as regards ed. 4 an entry ‘No. 500’ probably refers to the number printed, but it might be the order number. The cost of the first three eds. put together was £16 as compared with £18 for ed. 4 alone.

[1e] Observations on some passages in an Article in the Edinburgh Review, on the Depreciation of Paper Currency; also Suggestions for securing to the Public a Currency as Invariable as Gold, with a very moderate Supply of that Metal. [rule] Being the Appendix to the Fourth Edition of “High Price of Bullion,” &c. [rule] By David Ricardo. [tapering rule]

London: Printed for John Murray, 32, Fleet-street; William Blackwood, Edinburgh; and M. N. Mahon, Dublin. [rule] 1811.

Edition: current; Page: [359]

Collation: [A]2 B-C8; 18 leaves.

Contents: [A]1 half-title Appendix to Ricardo on Bullion. [double rule] 2s. [rule] T. Davison, Lombard-street, Whitefriars, London. [A]1v blank; [A]2 title-page; [A]2v blank; B1-C8 (pp. [1]–31) text; C8v imprint [double rule] T. Davison, Lombard-street, Whitefriars, London. [double rule]

[1f ] The High Price of Bullion...

Included in [9], Works ed. by McCulloch, 1846 etc.

[1g] The High Price of Bullion...

Included (without the Appendix) in A Select Collection of Scarce and Valuable Tracts and other Publications on Paper Currency and Banking, [edited by J. R. McCulloch, printed for Lord Overstone] London, 1857

Note: 150 copies printed.

[1h] The High Price of Bullion....

Included in [13], Economic Essays ed. by Gonner, 1923 etc.

[2a] Reply to Mr. Bosanquet’s Practical Observations on the Report of the Bullion Committee. [double rule] By David Ricardo. [double rule]

London: Printed for John Murray, 32, Fleet-street; William Blackwood, Edinburgh; and M. N. Mahon, Dublin. [rule] 1811.

Collation: [A]4 B-K8; 76 leaves. An Errata slip with five entries was issued and is found in some copies.

Contents: [A]1 half-title [double rule] Reply to Mr. Bosanquet’s Observations on the Report of the Bullion Committee. [double rule] Price 4s. [rule] T. Davison, Lombard-street, Whitefriars, London. [A]1v blank; [A]2 title-page; [A]2v blank; [A]3–4 (pp. [v]-vii) Contents; (A)4v blank; B1-I7 (pp. [1]–125) text; I7v (p. [126]) blank; I8-K7 (pp. [127]–141) Appendix; K7v-8 blank; K8v imprint [double rule] T. Davison, Lombard-street, Whitefriars, London. [double rule]

Note: 750 copies were printed.

[2b] Reply to Mr. Bosanquet....

Included in [9], Works ed. by McCulloch, 1846 etc.

Edition: current; Page: [360]

[2c] Reply to Mr. Bosanquet...

Included in [13], Economic Essays ed. by Gonner, 1923 etc.

[3a] An Essay on The Influence of a low Price of Corn on the Profits of Stock; shewing the Inexpediency of Restrictions on Importation: with Remarks on Mr. Malthus’ two last Publications: “An Inquiry into the Nature and Progress of Rent;” and “The Grounds of an Opinion on the Policy of restricting the Importation of Foreign Corn.” [double rule] By David Ricardo, Esq. [double rule]

London: Printed for John Murray, Albemarle Street.1815.

Collation: B-H4; 28 leaves. H3 and H4 are folded round the rest of the pamphlet so as to enclose it and form its half-title and title.

Contents: H3 half-title An Essay, &c. [rule] 3s.; H3v blank; H4 title-page; H4v imprint [rule] J. F. Dove, Printer, St. John’s Square.; B1–1v (pp. [1]–2) Introduction; B2-H1v (pp. [3]–50) text, and at bottom of the last page imprint [rule] J. F. Dove, Printer, St. John’s Square, London. [rule]; H2 blank; H2v advertisement Just Published [four Titles: Malthus’s Observations on the Corn Laws, Third Ed., 2s. 6d., Grounds of an Opinion, 2s. 6d., Inquiry into...Rent, 3s. and Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations, A new Edition...by David Buchanan, 4 vol. 8vo. 2l. 8s.]

Note: In Murray’s ledgers there is a single entry for this pamphlet, ‘Printing 500’, which presumably includes the ‘second edition’ issued immediately after.

[3b] An Essay...[as 3a up to ‘Ricardo, Esq.’] [double rule] Second Edition [double rule]

London: Printed for John Murray, Albemarle Street.1815.

Collation and Contents: Generally as in [3a]; the advertisement leaf, H2, however, is missing in all the copies examined.

Note: This ‘edition’ is identical with [3a] even in typographical detail (e.g. a displaced ‘t’ on p. 34, l. 1) and was obviously printed from the same standing type.

Edition: current; Page: [361]

[3c] An Essay on the Influence of a Low Price of Corn on the Profits of Stock...

Included in [9], Works ed. by McCulloch, 1846 etc.

[3d] An Essay on the Influence of a Low Price of Corn on the Profits of Stock...

Included in [13], Economic Essays ed. by Gonner, 1923 etc.

[4a] Proposals for an Economical and Secure Currency; with Observations on the Profits of the Bank of England, as they regard the Public and the Proprietors of Bank Stock. [double rule] By David Ricardo, Esq. [double rule]

London: Printed for John Murray, Albemarle-street. [rule] 1816.

Collation: [A]2 B-I8; 66 leaves.

Contents: [A]1 half-title Proposals for an Economical and Secure Currency. [rule] T. Davison, Lombard-street, Whitefriars, London. [A]1v blank; [A]2 title-page; [A]2v blank; B1–3v (pp. [1]–6) Introduction; B4-H1 (pp. [7]–97) text; H1v(p. [98]) blank; H2-I7v (pp. [99]–126) Appendix [printed in smaller type]; I8 blank; I8v imprint [double rule] T. Davison, Lombard-street, Whitefriars, London. [double rule]

Note: 500 copies were printed. Price 4s. 6d.

[4b] Proposals for an Economical and Secure Currency; with Observations on the Profits of the Bank of England, as they regard the Public and the Proprietors of Bank Stock. [double rule] By David Ricardo, Esq. [double rule] Second Edition. [tapering rule]

London: Printed for John Murray, Albemarle-street. [rule] 1816.

Collation: [A]2 B-I8; 66 leaves.

Contents: [A]1 half-title Second Edition. [rule] Proposals for an Economical and Secure Currency. [rule] 4s. 6d. [rule] T. Davison, Lombard-street, Whitefriars, London. [A]1v blank; Edition: current; Page: [362][A]2 title-page; [A]2v blank; B1–3v (pp. [1]–6) Introduction; B4-H2 (pp. [7]–99) text; H2v (p. [100]) blank; H3-I8v (pp. [101]–128) Appendix [printed in smaller type], and at the bottom of I8v advertisement In a few Days will be published, The Speech of Pascoe Grenfell, Esq., delivered...on Tuesday, Feb. 13, 1816...3s. 6d. and imprint T. Davison, Lombard-street, Whitefriars, London.

Note: 500 copies were printed.

[4c] Proposals for an Economical and Secure Currency; with Observations on the Profits of the Bank of England, as they regard the Public and the Proprietors of Bank Stock. [rule] By David Ricardo, Esq. [rule] Third Edition. [rule]

London: John Murray, Albemarle-street. [rule]1819.

Collation: [A]2 B-I8; 66 leaves.

Contents: [A]1 half-title Third Edition. [rule] Proposals for an Economical and Secure Currency. [rule] 4s. 6d. [A]1v blank;[A]2 title-page; [A]2v imprint [rule] Printed by W. Clowes, Northumberland-court, Strand, London. [rule]; B1–3v (pp. [1]–6) Introduction; B4-H2 (pp. [7]–99) text; H2v (p. [100]) blank; H3-I8v (pp. [101]–128) Appendix [printed in smaller type], and at the bottom of I8v imprint London: Printed by W. Clowes, Northumberland-court, Strand.

Note: 750 copies were printed.

[4d] Proposals for an Economical and Secure Currency...

Included in [9], Works ed. by McCulloch, 1846 etc.

[4e] Proposals for an Economical and Secure Currency...

Included (without Appendix V) in [13], Economic Essays ed. by Gonner, 1923 etc.

[5a] On the Principles of Political Economy, and Taxation. [rule] By David Ricardo, Esq. [rule]

London: John Murray, Albemarle-street. [rule]1817.

Edition: current; Page: [363]

Collation: [A]4 B-Z8 2A-2P8 2Q4 2R2; 306 leaves.

Contents: [A]1 title-page; [A]1v imprint [rule] J. M’Creery, Printer, Black Horse Court, London. [A]2–3v (pp. [iii]-vi) Preface; [A]4–4v (pp. [vii]-viii) Contents; B1–2P7 (pp. [1]–589) text; 2P7v Errata [four corrections referring to pp. 190, 521, 543, 555]; 2P8–2R2 Index, and at the bottom of 2R2 imprint J. M’Creery, Printer, Black-Horse-court, London.; 2R2v blank.

Cancel: Leaves 6, 7 and 8 of signature P (pp. 219–224) are cancels: P6 and P7 in cancel state are conjugate and appear to have been imposed with the two leaves of 2R to form a half-sheet. See above, I, xxviii-xxx and (for reference to a copy which has P6 and P7 in both pre-cancel and cancel states) below, p. 403.

Binding: Brown paper boards with printed label on spine:

[double rule] | ricardo | on | political | economy | [rule] | 14s. | [double rule]. This is the usual binding, no doubt as issued by Murray. Some booksellers, however, used to buy copies in sheet and have them bound on their own, though with the same printed label (e.g. one copy examined, which is in blue boards with brown back, has Constable’s catalogue dated 20 March 1818 bound in).

Note: 750 copies were printed.

[5b] On the Principles of Political Economy, and Taxation. [rule] By David Ricardo, Esq. [rule] Second Edition.

London: John Murray, Albemarle-street. [rule] 1819.

Collation: [A]4 B-Z8 AA-MM8 NN4; 280 leaves. Contents: [A]1 title-page; [A]1v imprint G. Woodfall, Printer, Angel-court, Skinner-street, London. [A]2–3v (pp. [iii]-vi) Preface; [A]4–4v (pp. [vii]-viii) Contents; B1-MM 4 (pp. [1]–535) text; MM 4v (p. [536]) blank; MM 5-NN 3v (pp. [537]–550) Index, and at the bottom of NN 3v (p. 550) imprint G. Woodfall, Printer, Angel Court, Skinner Street, London. NN 4 advertisement Tracts By the Same Author [four titles] and Preparing for Publication, The Principles of Political Economy considered, with a View to their practical Application. By T. R. Malthus, A.M. 8vo. NN 4v advertisement Tracts Lately Published [nine titles by various authors].

Edition: current; Page: [364]

Binding: Brown paper boards with printed label on spine: [double rule] | ricardo | on | political | economy. | [rule] | second edition. | [rule] | Price 14s. | [double rule].

Note: 1000 copies were printed.

[5c] On the Principles of Political Economy, and Taxation. [rule] By David Ricardo, Esq. [rule] Third Edition. [rule]

London: John Murray, Albemarle-street. [rule] 1821.

Collations: [*]2 a4 B-Z8 AA-LL8 MM6; 276 leaves.

Contents: [*]1 half-title On the Principles of Political Economy, and Taxation. [*]1v blank; [*]2 title-page; [*]2v imprint G. Woodfall, Printer, Angel-court, Skinner-street, London. a1–2v (pp. [v]-viii) Preface; a3–3v (pp. [ix]-x) Advertisement to the Third Edition; a4–4v (pp. [xi]-xii) Contents; B1-LL 5 (pp. [1]–521) text; LL 5v (p. [522]) blank; LL 6-MM 5v (pp. [523]–538) Index, and at the bottom of MM 5v (p. 538) imprint G. Woodfall, Printer, Angel Court, Skinner Street, London. MM 6–6v blank.

Variant: Signature 2P exists in two states, according as the last line of 2P7 (the end of the text) has the word ‘differently’ or the word ‘variously’ (this being clearly the later version). See the ‘Corrections’, below, p. 411, referring to I, 429.

Binding: Paper boards, blue sides and brown spine, with printed label: [double rule] | ricardo | on | political | economy. | [rule] | Price 12s. | [double rule]

Notes: From ‘unopened’ copies it appears that MM was printed as a complete octavo sheet and that the two central leaves were cut out, these presumably being the title-leaves here denoted as [*].

In this edition there are running-titles to each page giving the number and title of the Chapter.

1000 copies were printed.

[5d] On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation...

Included in [9], Works ed. by McCulloch, 1846 etc.

[5e] Principles of Political Economy and Taxation, by David Ricardo. Edited, with Introductory Essay, Notes, and Appendices, by E. C. K. Gonner, M.A., Lecturer on Economic Science, University College, Liverpool.

Edition: current; Page: [365]

London: George Bell and Sons, York Street Covent Garden. 1891.

pp. lxii, 2, 455.

A volume in Bohn’s Economic Library. Bound in cloth, price 5s., raised to 6s. after the first World War.

The edition contains an analytical table of contents and bibliographies of ‘Works by Ricardo’ (pp. 439–40) and of ‘Chief Works on Ricardo’ (pp. 441–46). The text is that of ed. 3. It has been ‘paragraphed’ by the editor; that is, divided into 151 numbered sections. The editorial notes indicate some of the variants of the earlier editions and also the minor errors which crept into McCulloch’s ed. Comparison of the latter with ed. 3 must have been given up before the last few pages, since no mention is made of the only deliberate omission by McCulloch which occurs near the end (see above, I, 426, n.).

The first printing was of 1500 copies. There were reprints in 1895, 1903, 1907, 1911, 1913, 1919, 1922, 1924, 1925, 1927 and 1929 aggregating a further 8250 copies.

[5f ] The Principles of Political Economy and Taxation by David Ricardo

London: Published by J. M. Dent & Sons Ltd. and in New York by E. P. Dutton & Co [1912]

pp. xvi, 300.

A volume in Everyman’s Library. Bound in ordinary cloth, price 2s., and library edition, 3s.

Introduction by F. W. Kolthammer, pp. vii-xiii.

First printing, 10,000 copies; reprinted 1917, 1923, 1926 and 1929, each impression of 4000 copies.

[6a] On Protection to Agriculture. By David Ricardo, Esq. M.P. [rule]

London: John Murray, Albemarle-street. [rule] mdcccxxii.

Collation: [A]2 B-G8; 50 leaves, plus an inserted folding table.

Contents: [A]1 title-page; [A]1v imprint London: Printed by William Clowes, Northumberland-court. [A]2 Contents;[A]2v blank; B1–1v (pp. [1]–2) Introduction; B2-G4 (pp. [3]–87) text; G4v (p. [88]) blank; G5–7v (pp. [89]–94) Appendix Edition: current; Page: [366]A [printed in smaller type]; inserted folding table (p. 95) Appendix B [printed in smaller type]; G8 imprint London: Printed by William Clowes, Northumberland-court.; G8v blank.

Note: 500 copies printed. Price 3s.

[6b] On Protection to Agriculture. By David Ricardo, Esq. M.P. [rule] Second Edition. [rule]

London: John Murray, Albemarle-street. [rule] mdcccxxii.

Collation and Contents as in [6a].

Note: 250 copies printed.

[6c] On Protection to Agriculture. By David Ricardo, Esq. M.P. [rule] Third Edition. [rule]

London: John Murray, Albemarle-street. [rule] mdcccxxii.

Collation and Contents as in [6a].

Note: 250 copies printed.

[6d] On Protection to Agriculture. By David Ricardo, Esq. M.P. [rule] Fourth Edition. [rule]

London: John Murray, Albemarle-street. [rule] mdcccxxii.

Collation and Contents as in [6a].

Note: two impressions of 250 copies each.

[6e] On Protection to Agriculture.

Included in [9], Works ed. by McCulloch, 1846 etc.

[6f ] On Protection to Agriculture.

Included in [13], Economic Essays ed. by Gonner, 1923 etc.

[7] Mr. Ricardo’s Speech on Mr. Western’s Motion, for a Committee to consider the Effects produced by the Edition: current; Page: [367]Resumption of Cash Payments, delivered the 12th of June, 1822. [rule]

London: Printed by G. Harvey, Crane-court, Fleet-street. [rule] 1822.

Collation: [A]8; 8 leaves.

Contents: [A]1 title; [A]1v blank; [A]2–7v (pp. 3–14) text, with imprint repeated at bottom of p. 14; [A]8–8v blank.

[8a] Plan for the Establishment of a National Bank. [tapering rule] By (the late) David Ricardo, Esq. M.P. [double rule]

London: John Murray, Albemarle-street. mdcccxxiv.

Collation: [*]2 A-B8 C2; 20 leaves.

Contents:[*]1 half-title Plan for a National Bank. [double rule]; [*]1v imprint [double rule] London: Printed by C. Roworth, Bell Yard, Temple Bar. [double rule]; [*]2 title-page; [*]2v blank; A1–1v (pp. [v]-vi) Preface; A2-C1v (pp. [1]–32) text; C2 advertisement Works of the late David Ricardo, Esq. M.P. [six titles; unusual features are that of The High Price of Bullion the third edition is listed, 2s., of the Essay on Profits the first, and of the Economical and Secure Currency the second]; C2v imprint [double rule] London: Printed by C. Roworth, Bell-yard, Temple-bar. [double rule]

Note: 500 copies were printed. Price 2s. 6d.

[8b] Plan for a National Bank.

Reprinted as an Appendix to A National Bank the Remedy for the Evils attendant upon our Present System of Paper Currency, by Samson Ricardo, Esq., London, Pelham Richardson, 1838, pp. 49–65.

[8c] Plan for the Establishment of a National Bank.

Included in [9], Works ed. by McCulloch, 1846 etc.

[8d] Plan for the Establishment of a National Bank.

Reprinted as a Supplement to History of the Bank of Edition: current; Page: [368]England, by A. Andréadès, London, P. S. King & Son, 1909, pp. 417–427.

[9] The Works of David Ricardo, Esq., M.P. With a Notice of the Life and Writings of the Author, By J. R. McCulloch, Esq.

London: John Murray, Albemarle Street. mdcccxlvi

Collation: [a]8 b-c8 B-Z8 AA-NN8 OO4; 308 leaves.

Contents: p. [i] half-title The Works of David Ricardo, Esq., M.P.; p. [iii] title-page; p. [v] ‘Advertisement’ [editorial note dated London, April 1846]; pp. [vii]-xiv Contents; pp. xv-xxxiii Life and Writings of Mr Ricardo [the last page is numbered xxxiii, but the subsequent pagination presupposes that it should be 1]; pp. [3]–260 Principles of Political Economy, 3rd ed.; pp. [261]– 301 High Price of Bullion, 4th ed.; pp. [303]–366 Reply to Mr. Bosanquet; pp. [367]–390 Essay on the Influence of a Low Price of Corn, 2nd ed.; pp. [391]–454 Proposals for an Economical and Secure Currency, 2nd ed.; pp. [455]–498 On Protection to Agriculture, 4th ed.; pp. [499]–512 Plan for a National Bank; pp. [513]–548 Essay on the Funding System, pp. [549]–556 Observations on Parliamentary Reform; pp. [557]–564 Speech on the Plan of Voting by Ballot; pp. [565]–584 Index. At bottom of p. 584 imprint Murray and Gibb, Printers, Edinburgh.

Notes: Bound in cloth, with Murray’s advertisements (variously dated, according to the time of binding) bound in at the end. Price 16s.

This edition was reprinted at intervals over half a century from the same setting. The dates of the impressions and the numbers printed in each case, as shown in Murray’s ledgers, were as follows:

| 1846 |

500 copies |

1876 |

250 copies |

| 1852 |

260 ,, |

1881 |

250 ,, |

| 1862 |

250 ,, |

1885 |

250 ,, |

| 1871 |

250 ,, |

1888 |

500 ,, |

It went out of print in 1913.

Copies of each of these have been traced (the reprint of 1885 bearing the date 1886) except that no copy has been found with the imprint of 1862. On the other hand there are two quite distinct variants dated 1852; one showing the year in roman, the other in arabic numerals. The ‘roman’ variant, Edition: current; Page: [369]like the 1846 impression, describes Ricardo on the title-page as ‘Esq., M.P.’ and McCulloch as ‘Esq.’, whereas the ‘arabic’ one, like the 1871 and subsequent impressions (all of them, incidentally, ‘arabic’), drops these titles and instead describes McCulloch as ‘Member of the Institute of France.’ Moreover, the ‘roman’, like the 1846 impression, signs the third sheet ‘c ’, while the ‘arabic’, like the 1871 and subsequent ones, changes the signature of the third sheet to ‘A’. These two points make it certain that the ‘arabic’ is the later impression of the two. Since we know that there was a printing in 1862 and only one in 1852, we must conclude that the impression dated 1852 in arabic was really printed in 1862 with a wrong date. There remains, however, the anomaly, if this conclusion be true, that the ‘arabic 1852’ impression drops the portrait of Ricardo engraved by Holl which had first appeared as a frontispiece in the ‘roman’ 1852 issue and reappears from 1871 onwards. But, surprisingly enough, this actually confirms the 1862 theory: since Murray’s ledgers, while showing a charge for a portrait both in 1852 and 1871, show no such charge in 1862.

The copies of the ‘arabic 1852’ issue examined do not contain Murray’s advertisements at the end: these, when preserved, should bear dates of 1862 or later.

On the title-page, the ‘roman’ 1852 impression is described as ‘Second Edition’; the ‘arabic’ one has no such description, and the 1871 and subsequent ones have ‘New Edition. With a Portrait.’ From the 1876 impression onwards Ricardo’s Preface and his ‘Advertisement to the Third Edition’ of the Principles are transposed (although the second page of the former retains its page-number, 6).

Note on the Biography: The ‘Life and Writings’ of Ricardo, which McCulloch included in this volume, is only one of a succession of versions which he published at various times. Immediately after Ricardo’s death McCulloch wrote an obituary in the Scotsman of 17 Sept. 1823, and a few months later a long appreciation, ‘Works and Character of Mr Ricardo’, in the Scotsman of 6 December. These two, with extensive extracts from the Memoir by Ricardo’s brother, were the basis for his ‘Life and Writings of Mr Ricardo’. This appeared first in its finished form, unsigned, in the Edinburgh Annual Register for 1823, published by Constable in 1824. It was issued with minor modifications as a separate pamphlet, again unsigned, under the title Memoir of the Life and Writings of David Ricardo, Esq., M.P. (London, Printed by Richard Taylor, Edition: current; Page: [370]1825, pp. 32), probably in connection with the annual Ricardo Lectures which McCulloch delivered in London. It next formed the article on Ricardo in the 7th edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica (1830–1842), before appearing in 1846 in Ricardo’s Works. It appeared yet again with some further modifications in McCulloch’s Treatises and Essays, Edinburgh, 1853 (2nd ed. 1859), and in the 8th edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica (1853–1860).

Each of these shows significant alterations, several of which have been noticed above (I, xix, n. 5; II, xiv; IV, 8, n. 2 and 358; X, 39). Other alterations are of interest as showing McCulloch’s changed outlook over the years; such as his newfound benevolence for the Bank of England (‘it was wisely judged better’, according to the version of 1846, p. xxiii, to discontinue Ricardo’s ingot plan; whereas the 1824–25 version had attributed its abandonment to ‘the errors and misapprehensions of the Directors of the Bank of England’); or his growing admiration for Peel, which is first expressed in 1846, and rises to a climax in the version in Treatises and Essays (‘The most disinterested and truly patriotic minister that this country has had since the Revolution’). Moreover, a number of alterations when taken together clearly show that McCulloch’s adherence to Ricardo’s doctrines became more and more qualified as years went on (a fact noted by Mallet in a diary-entry of 10 Jan. 1834, in Political Economy Club, Cent. Vol., p. 254 and cp. p. 238). In particular, the emphasis in 1846 upon the abstract character of the principles established by Ricardo and upon the failure of his conclusions to ‘harmonise with what really takes place’ (p. xxv), contrasts with McCulloch’s denial in 1824–25 of the allegation that those doctrines were ‘merely speculative’: ‘On the contrary, they enter deeply into almost all the practical investigations of the science, and especially into those...which relate to the distribution of wealth.’

[10] Letters of David Ricardo to Thomas Robert Malthus 1810–1823 Edited by James Bonar M.A. Oxford, LL.D. Glasgow

Oxford At the Clarendon Press 1887

pp. xxiv, 251.

Bound in cloth, price 10s. 6d.

Edition: current; Page: [371]

[11] Letters written by David Ricardo during a Tour on the Continent

Privately Printed 1891 John Bellows, Gloucester

Quarto, pp. 105, bound in cloth.

[12] Letters of David Ricardo to Hutches Trower and Others 1811–1823 Edited by James Bonar M.A. Oxford, LL.D. Glasgow and J. H. Hollander Ph.D. Associate Professor of Finance, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore

Oxford At the Clarendon Press 1899

pp. xxiii, 240.

Bound in cloth, price 7s. 6d. An Erratum slip was issued for p. 61.

[13] Economic Essays by David Ricardo edited with Introductory Essay and Notes by E. C. K. Gonner, K.B.E., Litt.D. Late Professor of Economic Science in the University of Liverpool

London G. Bell and Sons, Ltd. 1923

pp. xxxvi, 315.

‘Designed as a companion’ volume (according to the Preface) to [5e], with each work similarly ‘paragraphed’. Contains High Price of Bullion, Reply to Mr Bosanquet, Proposals for an Economical and Secure Currency, Essay on the Influence of a Low Price of Corn on the Profits of Stock and On Protection to Agriculture.

Bound in cloth, price 6s. Reprinted in 1926. 1000 copies printed of each impression.

AMERICAN

On the Principles of Political Economy, and Taxation. By

David Ricardo, Esquire. First American Edition.

Georgetown, D.C. Published by Joseph Milligan.

Jacob Gideon, Junior, Printer, Washington City. 1819.

pp. viii, 448 and 8 (unnumbered) of Index.

Edition: current; Page: [372]

Contrary to the title-page, the imprint at the end of the volume is: Printed by Davis & Force, Publishers of the New Calendar. The numeration of chapters, including double-numbering, follows that of the 1st English edition, of which it is a reprint.

The idea of this edition seems to have been suggested to Milligan by McCulloch’s review in the Edinburgh for June 1818. When Thomas Jefferson heard of the project, he wrote to Milligan (12 Jan. 1819): ‘On receipt of your letter proposing to republish Ricardo, I turned to the Edinburgh review and read that article...If you do republish it I wish but doubt your seeing your own by it. It is a work in my opinion which will not stand the test of time and trial.’ After referring to the ‘muddy reasoning’ of Ricardo and of his Edinburgh critic, he concluded: ‘The reputation of the work will, I think, fall as soon as it comes to be read.’ Milligan, however, replied that he was going forward with an edition of 500 to 600 copies, being assured of 250 subscriptions from members of Congress and of the Government. (Quoted by G. Chinard, Jefferson et les Idéologues, Baltimore, The Johns Hopkins Press, 1925, pp. 186–7, and by E. Lowenthal in American Economic Review, Dec. 1952, vol. xlii, p. 878.)

(No confirmation has been found for a casual allusion to a Washington second edition of 1830 in M. J. L. O’Connor, Origins of Academic Economics in the United States, New York, 1944, p. 150.)

The First Six Chapters of the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation of David Ricardo 1817

New York Macmillan and Co. and London 1895

pp. xii, 118.

A volume in the series Economic Classics, edited by W. J. Ashley.

Bound in cloth, price $.75 (later raised to $1.50). First published in January 1895 (2160 copies), it was reprinted in 1909, 1913, 1914, 1921, 1923, 1927 and 1931 (the reprints totalling 5490 copies).

The differences between the texts of the first and third editions (1817 and 1821) are given, though with several omissions.

Letters of David Ricardo to John Ramsay McCulloch 1816– 1823 Edited, with introduction and annotations, byJ. H. Hollander, Ph.D. Instructor in Economics in the Johns Hopkins University

Edition: current; Page: [373]

September and November 1895. Published for the American Economic Association by Macmillan & Company New York. London: Swan Sonnenschein & Co.

pp. xxii, 185.

No. 5–6 of Publications of the American Economic Association, Vol. x (of which it forms pp. 613–819: both paginations are given in the headlines). The number was also issued separately bound in cloth.

Three Letters on The Price of Gold Contributed to The Morning Chronicle (London) in August-November, 1809 by David Ricardo

Baltimore The Johns Hopkins Press 1903

pp. 30, plus blank leaf at the end.

Issued in grey paper covers, bearing the title Three Letters on The Price of Gold by David Ricardo.

One of the series A Reprint of Economic Tracts Edited by Jacob H. Hollander, Ph.D. Associate Professor of Political Economy Johns Hopkins University.

Notes on Malthus’ “Principles of Political Economy” By David Ricardo Edited with an introduction and notes by Jacob H. Hollander and T. E. Gregory.

1928 The Johns Hopkins Press Baltimore, Maryland Humphrey Milford Oxford University Press Amen House, London, E.C. 4.

pp. 4 unnumbered, cvii, 246.

On the third unnumbered page: Semicentennial Publications of The Johns Hopkins University 1876–1926.

Bound in cloth, price $5.

Minor Papers on the Currency Question 1809–1823 By David Ricardo Edited with an introduction and notes by Jacob H. Hollander.

Baltimore The Johns Hopkins Press 1932.

pp. 2 blank, ix, 231.

Edition: current; Page: [374]

This volume contains an oddly assorted collection of papers, notes and jottings, as well as a few letters, from that bundle of the Ricardo Papers which is referred to below, p. 387, as having become separated from the main body and found with the Notes on Malthus in 1919.

Bound in cloth, price $3.

FRENCH

Le haut prix de l’or et de l’argent, considéré comme une preuve de la dépréciation des billets de banque. Troisièmeédition revue et augmentée; par David Ricardo. Londres,1810. (A translation of The High Price of Bullion published in three instalments in the Paris daily Gazette Nationale ou Le Moniteur Universel, Nos. 267, 268 and 269, of 24, 25 and 26 September 1810, under the general heading ‘Finances—Commerce’.)

This war-time translation was evidently unknown to Ricardo, and does not seem to have been noticed until Achille Loria drew attention to it with the statement that ‘Napoleon caused Ricardo’s essay to be translated in full in the Moniteur ’(Annali di Economia, 1925, vol. ii, p. 44).

Des Principes de l’Économie politique, et de l’impôt, par M. David Ricardo; traduit de l’anglais par F. S. Constancio, D.M., etc.; avec des notes explicatives et critiques, par M. Jean-Baptiste Say, Membre des Académies de St.-Pétersbourg, de Zurich, de Madrid, etc.; Professeur d’Économie politique à l’Athénée de Paris. Tome premier. [Tome second.]

A Paris, chez J. P. Aillaud, Libraire, Quai Voltaire, No 21. 1819.

pp. xii, 431 and vi, 375.

Although dated 1819, a copy had reached Ricardo by the middle of December 1818 and Say’s notes were discussed in letters between him and Mill of that month, above, VII, 361–2, 371, 375.

The translator, Francisco Solano Constancio, a Portuguese resident in Paris, was a doctor of medicine of Edinburgh University and in 1821 was appointed Portuguese Minister in Washington. In Edition: current; Page: [375]1820 he translated into French Malthus’s Political Economy for the same bookseller Aillaud; and when Malthus visited Paris in August of that year he was told that Ricardo’s work had already sold 900 copies (above, VIII, 225).

Des Principes de l’Économie politique et de l’impot, par David Ricardo; traduit de l’anglais par F.-S. Constancio, D.M., etc. avec des notes explicatives et critiques parJ.-B. Say, membre des Académies de Saint-Pétersbourg, de Zurich, de Madrid, etc., professeur d’Économie politique a l’Athénée de Paris. Seconde édition, Revue, corrigée et augmentée d’une notice sur la vie et les écrits de Ricardo, publiée par sa famille.—Tome premier. [Tome second.]—

Paris, J.-P. Aillaud, libraire, Quai Voltaire, ii.—1835.

pp. xl [misprinted lx], 378 and iv, 330.

Although described as ‘seconde édition’ it reproduces the preceding one and is therefore based on the text of the first English edition, without even the insertion of the chapter On Machinery. The Life of Ricardo prefixed to it is a translation of the memoir by McCulloch from the anonymous pamphlet of 1825 (mentioned above, under his edition of the Works, 1846).

Œuvres complètes de David Ricardo traduites en français par MM. Constancio et Alc. Fonteyraud, augmentées des notes de Jean-Baptiste Say, de nouvelles notes et de commentaires par Malthus, Sismondi, MM. Rossi, Blanqui, etc. et précédées d’une notice biographique sur la vie et les travaux de l’auteur, par M. Alcide Fonteyraud.

Paris, Guillaumin et Cie Libraires, 1847.

pp. xlviii, 752.

Vol. xiii in the Collection des principaux économistes; it contains all the works given in McCulloch’s edition with the exception of the two papers on Parliamentary Reform. This has provided for nearly a century the standard introduction to Ricardo for a large part of the non-English-speaking world. Yet the version of the Principles which it presents is no better than a pastiche of the first and third original editions. It is based on Constancio’s translation Edition: current; Page: [376]of ed. 1, revised (e.g. substituting ‘rente’ for ‘fermage’) by Fonteyraud who has also translated the most obvious passages added by Ricardo in ed. 3, including the new chapter On Machinery: the revision however is far from complete and much of the resulting text is still that of ed. 1. In one case indeed a long passage is translated twice, the version of the third edition being inserted after that of the first without noticing that they are almost identical (p. 375, ‘N’y aurait-il pas’ to p. 377, line 5, ‘abondance’ and p. 377, ‘N’arrive-t-il donc’ to p. 378, end of the second paragraph, ‘abondance ’).

Œuvres complètes de David Ricardo traduites en français par MM. Constancio et Alc. Fonteyraud augmentées de notes de J.-B. Say, Malthus, Sismondi, Rossi, Blanqui, etc. précédées d’une notice biographique sur la vie et les travaux de l’auteur par M. Alcide Fonteyraud et d’une préface par M. Maurice Block Membre de l’Institut

Paris, Guillaumin et Cie, Libraires, 1882

pp. xvi, xlviii, 707.

At the top of the title-page: ‘Collection des principaux économistes’. Apart from the addition of a short preface by Block, it is a reprint of the 1847 edition.

P. Beauregard—Ricardo—Rente, salaires et profits. Traduction revue par M. Formentin

Paris, Guillaumin et Cie [1888]

16 mo, pp. 6 not numbered, xxxiv, 224 and portrait.

Forms vol. vii of the Petite bibliothèque économique française etétrangère and contains eight chapters of the Principles with an Introduction by Paul Beauregard.

GERMAN

Die Grundsätze der politischen Oekonomie oder der Staatswirtschaft und des Besteuerung. Von David Ricardo, Esq. Nebst erläuternden und kritischen Anmerkungen von J. B. Say Aus dem Englischen, und, in Beziehung auf die Anmerkungen, aus dem Franzùsischen übersetzt von Christ. Aug. Schmidt.

Edition: current; Page: [377]

Weimar, im Verlage des Gr. H. S. priv. Landes-Industrie-Comptoirs, 1821.

pp. viii, 584.

David Ricardo’s Grundsätze der Volkswirthschaft und der Besteuerung. Aus dem Englischen übersetzt und erläutert von Dr. Edw. Baumstark.

Erster Theil. Leipzig, Verlag von Wilh. Engelmann. 1837.

pp. xxxii, 461.

Zweiter Band. Erläuterungen. Leipzig, Verlag von Wilh. Engelmann, 1838.

pp. xii, 830.

The first volume contains the translation of the Principles, the second the commentary. The translator explains in his preface that he has used the second English edition (1819) since, despite all his efforts, the third edition proved unobtainable both in England and in Germany.

David Ricardo’s Grundgesetze der Volkswirthschaft und Besteuerung. Aus dem Englischen übersetzt von Dr. Ed. Baumstark. Zweite, durchgesehene, verbesserte und vermehrte Auflage.

Leipzig, Verlag von Wilhelm Engelmann. 1877.

pp. xxiv, 396.

The translator says in the preface that this edition is based on the third English edition, as contained in the Works, ed. by McCulloch.

The commentary which had formed the second volume of the earlier Baumstark edition did not appear again until it was entirely rewritten by Karl Diehl as Sozialwissenschaftliche Erläuterungen, ‘Zweite, neu verfasste Auflage’, in 2 vols., Leipzig, Engelmann, 1905 (3rd ed., 1922).

Grundsätze der Volkswirtschaft und Besteuerung Von David Ricardo. Aus dem englischen Original, und zwar nach der Ausgabe letzter Hand (3. Auflage 1821), in’s Deutsche Edition: current; Page: [378]übertragen von Ottomar Thiele und eingeleitet von Heinrich Waentig.

Jena, Gustav Fischer, 1905, pp. xi, 444.

In the second edition (Jena, Fischer, 1921) the name of Thiele disappears as translator and the title-page reads, ‘ins Deutsche übertragen und eingeleitet von Professor Dr. Heinrich Waentig’: in his preface Waentig explains that owing to the many defects of the original translation it had been found necessary to revise it thoroughly and for him to assume full responsibility for the new text.

A third edition appeared in 1923 from the same publisher.

David Ricardo’s kleinere Schriften. I. Schriften über Getreidezölle. Aus dem englischen Original ins Deutsche übertragen und eingeleitet von Professor Dr E. Leser.

Jena, Gustav Fischer, 1905, pp. xx, 125.

Contains Essays on the Influence of a Low Price of Corn and On Protection to Agriculture. There was a second edition in 1922. Although this volume is described as Part I, the second part never appeared.

David Ricardo. Der hohe Preis der Edelmetalle, ein Beweis für die Entwertung der Banknoten. (In: Ausgewählte Lesestücke zum Studium der politischen Oekonomie, herausgegeben von Karl Diehl und Paul Mombert, Band 1. Zur Lehre vom Geld, Karlsruhe, G. Braun, 1910.)

A fourth ed. of this volume appeared in 1923. Subsequent volumes of this series of ‘readings’ contain translations of single chapters of Ricardo’s Principles, and Band xvi (1923) of his Funding System.

Ricardo’s Währungsplan aus dem Jahre 1816. Übersetzt von Dr. Wilhelm Fromowitz und Dr. Fritz Machlup. (Appendix to: Die Goldkernwährung, von Dr. Fritz Machlup, Halberstadt, H. Meyer, 1925, pp. 183–203.)

This is a translation of the first part of Economical and Secure Currency.

Edition: current; Page: [379]

Vorschläge für eine wirtschaftliche und sichere Währung. Von David Ricardo. Aus dem Englischen übertragen von Dr. Wilhelm Fromowitz und Dr. Fritz Machlup.

Halberstadt, H. Meyer, 1927, pp. 29.

This is a reprint of the previous item.

POLISH

Dawid Ricardo, O zasadach ekonomii politycznej i o podatku.

Vol. i, Warsaw, 1826, pp. x, 283; vol. ii, Warsaw, 1827, pp. 227.

This is a translation, by Stanislaw Kunatt, of the first English edition of the Principles. The translator was one of the two young Polish travellers whom Ricardo met on the Simplon in 1822; see above, p. 290, n.

Dawid Ricardo, Zasady ekonomji politycznej i podatkowania.

Warsaw, 1919, pp. xii, 357.

Translated by M. Bornsteinowa. Reprinted in 1929.

BELGIAN

Des Principes de l’Économie politique et de l’impot, par David Ricardo; traduit de l’anglais par F.-S. Constancio, D.M., etc. avec des notes explicatives et critiques parJ.-B. Say, membre des Académies de Saint-Pétersbourg, de Zurich, de Madrid, etc., professeur d’Économie politique a l’Athénée de Paris. Troisième édition, Revue, corrigée et augmentée d’une notice sur la vie et les écrits de Ricardo, publiée par sa famille.—

Bruxelles, H. Dumont, Libraire-éditeur.—1835.

pp. 310 [numbered i-xxii, 23–310].

This is a pirate reprint of the Paris ‘seconde édition’ of the same year; hence its claim to be a ‘troisième édition’. The text presented, however, is still that of the first London edition.

Edition: current; Page: [380]

DANISH

David Ricardo: Om Nationaloeconomiens og Beskatningens Grundsatninger.

Kopenhagen, 1839.

The translator was Ludvig Sophus Fallesen (1807–1840), a mathematician.

ITALIAN

David Ricardo—Principii dell’economia politica, con note di G. B. Say, Sismondi, McCulloch, Blanqui, Fonteyraud. (In: Biblioteca dell’economista, Prima serie, Trattati complessivi, vol. xi, pp. 365–642.)

Torino, Stamperia dell’Unione tipografico-editrice, 1856.

An introduction by the editor, Francesco Ferrara (pp. v-lxxvii), is mainly devoted to a criticism of Ricardo’s theory of value. The translation is from the 3rd English edition.

Ricardo—Opuscoli bancarii. (In: Biblioteca dell’economista, Seconda serie, Trattati speciali, vol. vi, Moneta e suoi surrogati, pp. 197–379.)

Torino, Stamperia dell’Unione tipografico-editrice,1857.

Includes four pamphlets: Dell’alto prezzo de’ metalli preziosi; Risposta alle osservazioni pratiche del signor Bosanquet; Proposta di una circolazione monetaria economica e sicura; Disegno della istituzione di un banco nazionale.

David Ricardo—Saggio sulla influenza del basso prezzo del grano sui profitti del capitale. (In: Biblioteca dell’economista, Seconda serie, Trattati speciali, vol. ii, Agricoltura e quistioni economiche che la riguardano, pp. 1049–1072.)

Torino, Stamperia dell’Unione tipografico-editrice, 1860.

Edition: current; Page: [381]

Ricardo—Intorno alla protezione accordata all’agricoltura. (In: Biblioteca dell’economista, Seconda serie, Trattati speciali, vol. viii, pp. 427–466.)

Torino, Stamperia dell’Unione tipografico-editrice, 1866.

RUSSIAN

Сочинения Давида Рикардо. Русский перевод Н. Зибера. Киев, Университетская тидография, 1875 г. (Works of David Ricardo, translated by N. Sieber. Kiev, University Press, 1875, pp. xxxiii, 327.)

500 copies were printed, according to the ‘Systematic Catalogue of Russian Books, 1875–76’ (Russian). The translator was Professor of Political Economy at the University of Kiev, and the first part of this translation had originally appeared in the ‘University Izvestia’ of 1873, Nos. 1–10 (see ‘Russian Biographical Dictionary’ of the Imperial Russian Historical Society, 1916).

Сочинения Давида Рикардо. Русский перевод Н. Зибера. Второе дополненное и исправленное издание с примечаниями от переводчика. С.-Петербург, издание Пантелеева, 1882 г. (Second edition of the preceding, completed and revised, with notes by the translator. St Petersburg, Panteleev, 1882, pp. 659.)

Contains all the writings in McCulloch’s edition of the Works. A third edition was published in 1897.

Давид Рикардо, Начала политической экономии. Перевод Н. В. Фабриканта. Под редакцией М. Щепкина и И. Вернера. Москва, изд. Солдатенкова, 1895 г. (Principles of Political Economy. Translated by N. V. Fabrikant. Edited by M. Shchepkin and I. Werner. Moscow, Soldatenkov, 1895.)

A volume in the ‘Library of Economists’.

Трактаты Мальтуса и Рикардо о ренте. Перевел А. Миклашевский. Юрьев, типограэия Н. Маттисена, Edition: current; Page: [382]1908 г. (Tracts by Malthus and Ricardo on Rent. Translated by A. Miklashevsky. Dorpat, Mattisen, 1908.)

Contains on pp. 97–128 Ricardo’s Essay on the Influence of a Low Price of Corn.

Давид Рикардо, Собрание сочинений, Перевод Н. Рязанова. С.-Петербург, 1908 г. (Collected Works, translated by N. Riazanov, St Petersburg, 1908.)

Mr. Kohanovsky, who reported this item, had seen only a first volume. This presumably consists of the translation of the Principles, which D. (alias N.) Riazanov mentions in his preface to the edition of 1929 (listed below) as having been published by ‘Zerno’ in 1908: curiously, however, it is not included in the bibliography at the end of the same 1929 edition.

Давид Рикардо, Начала политической экономии и податного обложения. Перевод с английского под редакцией Н. Рязанова. Москва, изд. ‘Звено’, 1910. (Principles of Political Economy and Taxation. Translation from the English, edited by N. Riazanov. Moscow, ‘Zveno’, 1910.)

Давид Рикардо, Принципы политической экономии. Сокращенный перевод с английского, под редакцией и с историко-критическим очерком Д. Р. Черныщева. Ленинград, изд. ‘Прибой’, 1924 г. (Principles of Political Economy. Abridged translation from the English, edited with an historical and critical essay by D. R. Chernishev. Leningrad, ‘Priboy’, 1924.)

Давид Рикардо, Высокая цена слютков есть доказательство обесценения банковых билетов. Сокращенный перевод. Сборник ‘Деньги’. Москва, изд. ‘Плановое хозяйство’, 1926 г. Теоретическая экономия в отрывках, стр. 89-119. (The High Price of Bullion. Abridged translation. Collection ‘Money’. Moscow, published by ‘Planned Economy’, 1926. Theoretical Economics in Selections, pp. 89–119.)

Edition: current; Page: [383]

Давид Рикардо, Экономические памфлеты. Перевод с английского под редакцией и с предисловием С. Б. Членова. Москва, изд. ‘Московский рабочий’, 1928 г. (Ricardo’s Economic Pamphlets. Translation from the English edited with an introduction by S. B. Chlenov. Moscow, published by ‘Moscow Worker’, 1928.)

Давид Рикардо, Начала политической экономии и податного обложения. Перевод, вступительная статья и примечания Г. Рязанова. Институт К. Маркса и ф. Энгельса. Государственное издательство, Москва, Ленинград, 1929 г. (Principles of Political Economy and Taxation. Translated, with introduction and notes, by D. Riazanov. Marx-Engels Institute. State Publishing House, Moscow-Leningrad, 1929, pp. xxxix, 368.)

Contains a bibliography of Russian literature on Ricardo, pp. 354–366.

HUNGARIAN

Ricardo Dávid: A közgazdaságtan és adózás alapelvei. Forditotta: Láng Lajos. (The Principles, translated by L. Lang: vol. 5 of the ‘Collection of Economic Writers’.) Budapest, Pallas, 1892.

Ricardo: Levelek Malthushoz. Angolból forditották: Jónás János és gróf Eszterházy Mihály. (Letters to Malthus, translated by J. Jonas and Count M. Esterhazy: vol. xiv of the ‘Hungarian Economic Library’.)

Budapest, Grill, 1913.

JAPANESE

Essays on Currency and Finance by David Ricardo, edited by C. S. Griffin, A.M., Professor of Political Economy and Finance, Imperial University of Tokyo. Tokyo and Osaka, Maruzen Co., 1901, pp. vi, 237.

Edition: current; Page: [384]

The above is an edition in English of The High Price of Bullion, Reply to Mr Bosanquet, Economical Currency, Plan for a National Bank, Funding System.

Principles of Political Economy (Chapters 1–7, 19–21, 24, 30–32), translated by Tsuneo Hori. Tokyo, Iwanami-Shoten, 1921.

Principles of Political Economy (Chapters 1–6, 21, 30), translated by Saichiro Wada. Tokyo, Uchida-Rôkakuho, 1921.

The High Price of Bullion, translated by Motoyuki Takabatake and Hiroshi Abe (a volume in the series ‘Economic Doctrines’). Tokyo, Jiryu-sha, 1925.

Essay on the Influence of a Low Price of Corn on the Profits of Stock, translated by Toyokichi Yamamoto (in ‘Studies in Economics’, vol. 4, No. 3, July 1927).

The High Price of Bullion (without the Appendix) and extracts from Proposals for an Economical and Secure Currency, translated by Akeo Hashizume (in his own book ‘Theories of Money’, Chapters viii and ix). Tokyo, Nihon-Hyoronsha, 1928.

Principles of Political Economy, translated by Shinzo Koizumi (a volume in ‘Iwanami Library’). Tokyo, Iwanami-Shoten, 1928.

Principles of Political Economy, translated by Tsuneo Hori. Kyoto, Kôbundo-Shobô, 1928.

The text of the original 3rd ed. with the variants of the 1st and 2nd eds.

Principles of Political Economy, translated by Shinzo Koizumi (a volume in the series ‘Economic Classics’). Tokyo, Iwanami-Shoten, 1930.

Edition: current; Page: [385]

This is a new edition of Professor Koizumi’s translation of 1928, with the addition of an introduction and notes, in which the texts of the three original editions are compared.

Ricardo’s Works on Money and Banking, translated by Shigeo Obata. Tokyo, Dôbun-kan, 1931.

This includes The Price of Gold, The High Price of Bullion, Reply to Mr Bosanquet, Economical Currency, Plan for a National Bank.

Essays on the Influence of a Low Price of Corn, Principles of Political Economy, On Protection to Agriculture, translated by Hideo Yoshida and Akira Kinoshita (a volume in the series ‘Sekai-Daishiso-Zenshu’). Tokyo, Shunjû-sha,1932.

INDIAN

Ricardo’s Principles of Political Economy and Taxation, translated into Bengali by Sudha-Kanta De (in the periodical Arthic Unnati [Economic Progress], Calcutta, 1928–30).

CHINESE

Principles of Political Economy and Taxation, by David Ricardo, translated by Tso-liang Chen. Shanghai, Hua T’ung Book Company, 1930.

Principles of Political Economy and Taxation, by David Ricardo, translated by Ta-li Kuo and Ya-nan Wang. Shanghai, Shen Chow Kuo Kuang Book Company, 1931.

Principles of Political Economy and Taxation, by David Ricardo, [English text] abridged with notes in Chinese by Chuan Shih Li. Shanghai, The Commercial Press Limited, 1931.