Edition: orig; Page: [433] THE I N D E X.

N.B. The Roman Figures refer to the Preface.

A.

A Belard, page 101.

Absurd, nothing is thought so that we have been used to, 159.

Absurdities in sacred matters not incompatible with Politeness and worldly Wisdom, 243, 244. 249.

Acclamations made at Church, 163.

Active, stirring Man. The difference between such a one, and an easy indolent Man in the same Circumstances, from 108 to 120.

Accomplishments. The Foundation of them is laid in our Youth, 412.

Adam. All Men are his Descendants, 220. was not predestinated to fall, 271. A miraculous Production, 370.

Administration (the civil) how it ought to be contriv’d, 389. What Men it requires, ibid. 390. most Branches of it seem to be more difficult than they are, ibid. Is wisely divided in several Branches, 393. Is a Ship that never lies at Anchor, 404.

Affections of the Mind mechanically influence the Body, 175.

Affectionate Scheme, 293. would have been inconsistent with the present Plan, 294. When it might take place, 303.

Age (the golden) fabulous, 367. Inconsistent with human Nature, 370.

Alexander Severus, his absurd Worship, 243.

Edition: orig; Page: [434]Americans. The disadvantage they labour’d under, 383. may be very ancient, ibid. 384.

Ananas (the) or Pine-apple excels all other Fruit, 218. To whom we owe the Production and Culture of it in England, 219.

Edition: current; Page: [360]

Anaxagoras. The only Man in Antiquity that really despised Riches and Honour, 113.

Anger, describ’d, 193. The Origin of it in Nature, ibid. What Creatures have most Anger, 194. The natural way of Venting Anger is by fighting, 351.

Animal Oeconomy. Man contributes nothing to it, 257.

Animals (all) of the same Species intelligible to one another, 337.

Antagonists (the) of prime Ministers, 396, 397. are seldom better than the Ministers themselves, 406.

Applause, always grateful, 164. The Charms of it, page xx.

Arts and Sciences. What encourages them, 414. which will always be the most lucrative, 423.

Atheism and Superstition, of the same Origin, 374. What People are most in danger of Atheism, 375. Atheism may be abhorr’d by Men of little Religion, x.

Atheists may be Men of good Morals, 376.

Avarice. What ought to be deem’d as such, x [xiv].

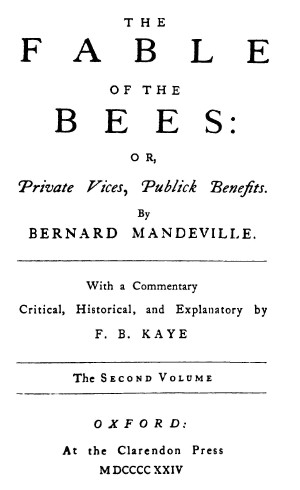

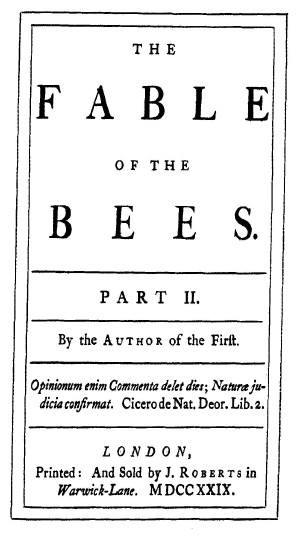

Author of the Fable of the Bees (the) desires not to conceal any thing that has been said against him, ii. The reason of his Silence, ibid. How far only he defends his Book, iii. Has call’d it an inconsiderable Trifle and a Rhapsody, ibid. iv. Was unjustly censured for confessing his Vanity, v. How far he is answerable for what Horatio says, xxv. His Fears of what will happen, xxvi. The Report of his having burnt his Book, xxvii. The Preparatory Contrivance this Report was built upon, xxx, xxxi.

Authors compared to Architects, 362. ought to be upon the same footing with their Criticks, i. When most foolishly employ’d, iii.

B.

Bears brought forth chiefly in cold Countries, 273.

Bear-Gardens not inferiour to Opera’s as to the real Virtue of the Companies that frequent either, 41.

Edition: orig; Page: [435]Beau Monde censured, 98. what has always employ’d the Wishes of them, 156. are every where the Judges and Refiners of Language, 346, 347. A Character of a considerable part of the Beau Monde throughout Christendom, x. The Indulgence of the Beau Monde censured, xi, xii, xiii, xiv, xv. Their easy Compliance with Ceremonies in Divine Worship, xvii. Exceptions from the generality of them, ibid.

Bees (in) Society is natural, in Man artificial, 205, 206, 207.

Behaviour (the) of a fine Gentleman at his own Table, 52. Abroad, ibid. To his Tenants, 55. To his Servants, 56. To Tradesmen, 57. Of an indolent Man of no Fortune, 108, 109. Of an active Man in the same Circumstances, 110. Of Men meanly born, 359. Of Savages, 137, 138. 227, 228. Of the ill-bred Vulgar, 336. Of different Parties, 406, 407

Edition: current; Page: [361]

Believing. The necessity of it, 378.

Blessing (a) there is nothing created that is always so, 140. The Children of the Poor one of the greatest Blessings, 302.

Bodies (our) visibly contriv’d not to last, 284.

Brain (the) compared to a Spring-Watch, 177. 180. The Oeconomy of it unknown, 178. Conjectures on the Use of it, 179. 183. Of Infants compared to a Slate and a Sampler, 184. The Labour of the Brain, 187. The Brain more accurate in Women than it is in Men, 189.

Brutes have Privileges and Instincts which Men have not, 338.

C.

Cardinals (the most valuable Accomplishments among) 34, 35.

Care (what ought to employ our first) 131.

Carthaginians. Their abominable Worship, 243.

Castrati. See Eunuchs.

Castration. The Effects of it upon the Voice, 100.

Cat-calls, 166.

Cato. His Self-denial, vi.

Centaurs, Sphinxes and Dragons. Their Origin, 266, 267.

Edition: orig; Page: [436]Chance. What it is, 305, 306.

Chancelor (the Lord) of Great Brittain. What he should be, 389. His Post requires greater Qualifications than any other, 395.

Charity often counterfeited, 120. The World hates those who detect the Counterfeits, 121. An instance of an unjust Pretence to Charity, ibid. 122.

Chastity. The World’s Opinion about it, xiii.

Children of the Poor, one of the greatest Blessings, 302. What their Lot always will be, 424. 426.

Children. What they are indebted for to Parents, 255. Whether People marry with design of having them, 259. The Children of Savages when sociable, 226.

Christianity (the Essentials of) never to be talk’d of among the Beau Monde, xi.

Cicero imitated Plato, vi [viii].

Cid. The six famous Lines of it censured, 354, 355.

Cities (great flourishing) the Work of Providence, 385. What is requisite to govern them, 386.

Claim (the unjust) Men lay to every thing that is laudable, 237. 257.

Cleomenes begs of Horatio to accept of the Fable of the Bees, and read it, 37. is denied, 38. Thinking Horatio displeas’d, breaks off the Discourse, 59, 60. But Horatio owning himself in the wrong, is persuaded again to go on, 61. Shews himself not uncharitable or censorious, 65. Gives Reasons why well-accomplish’d Persons may be ignorant of the Principles they act from, 66, 67. Explodes Duelling, demonstrates the Laws of Honour to be clashing with the Edition: current; Page: [362] Laws of God, from 72 to 97. Shews the false Pretences that are made to Virtue, from 107 to 123. His Maxim of enquiring into the Rise of Arts and Inventions, 133. Gives his Conjectures concerning the Origin of Politeness, from 134 to 154. Shews the Inconsistency of the Affectionate Scheme with the World as it is, from 294 to 304. Proves his Assertions, concerning the Nature of Man, from the Tendency of all Laws, especially the Ten Commandments, from 315 to 335. Gives his Opinion concerning the different Designs Lord Shaftsbury and his Friend have wrote with, 431, 432. His Character, xviii, &c. His censuring of his own Actions, xx. His Aversion to Contempt, xxii.

Edition: orig; Page: [437]Clergyman (the social) 25. Why many Clergymen are angry with the Fable of the Bees, 99.

Combabus, 101.

Commandments (the Ten) are a strong Proof of the Principle of Selfishness and Instinct of Sovereignty in human Nature, 318. 320. All of them have their Political Uses, 333. 335. What is implied in the Ninth Commandment, 321. What may be inferr’d from the Sixth, 322. The two first point at our natural Blindness and Ignorance of the true Deity, 324. The Purport of the Third discuss’d, 327, 328, 329. the Fifth explain’d, 330, 331, 332. The Usefulness of the Fourth in worldly Affairs, 333, 334.

Company. Why Man loves it, 203.

Compliments, which are Gothick, 160. not begun among Equals, 161. lose their Dignity, 162.

Conclaves (a Character of) 35.

Confidence repos’d in Prime Ministers, 402, 403.

Confucius, 379.

Conjectures on the Origin of Politeness, 134. 145. On the first Motive that could make Savages associate, 264. This Conjecture not clashing with any of the Divine Attributes, 281, 282. 292. 305. 307.

Consciousness. What it consists in, 191.

Constitution (the) 393. The Wisdom of that of Great Britain, 394. Is chiefly to be taken care of in all Countries, 404.

Constructions (the kind) of the Beau Monde, xiv, xv. are hurtful to the Practice of Christianity, xvi.

Contracts never lasting among Savages, 313.

Corneille cited, 354. Defended, 356, 357.

Covetousness. What People are not tax’d with it by the Beau Monde, xv.

Councelor (the Social) 24.

Courage (artificial) 78. Why it does not appear in Dangers where Honour is not concern’d, 91, 92. is the most useful in War, 364. may be procured by Discipline, 382.

Courage (natural) 77. impudent Pretences to it, 364.

Courtiers. Their Business, 399.

Courts of Princes. What procures Men Admittance there, 363.

Edition: current; Page: [363]

Edition: orig; Page: [438] Creatures. How some came to be talk’d of that never had any Existence, 266, 267.

Creatures (living) compared to an Engine that raises Water by Fire, 181. The Production of their Numbers in every Species proportion’d to the Consumption of them, 289. This is very conspicuous in Whales, ibid.

Cruelty. Not greater in a Wolf that eats a Man than it is in a Man who eats a Chicken, 281.

D.

Danger (the) from wild Beasts the first Inducement to make Savages associate, 264, 265. The Effects of it upon Man’s Fear, ibid. 266. Objections to this Conjecture, 267. 271. 275. 280, 281. 283. 304, 305. This Danger is what our Species will never be entirely exempt from upon Earth, 309.

Death (it is) and not the manner of Dying to which our Aversion is universal, 284, 285.

Debate (a) about Pride, and what sort of People are most affected with it, 48, 49, 50. About Money to Servants, 56, 57. About the Principles a fine Gentleman may act from, 61, 62, 63. About which it is that enclines Men most to be Religious, Fear or Gratitude, from 237 to 247. About the first Step to Society, from 264 to 309.

Deism (modern) what has encreas’d it in this Kingdom, 376. no greater Tie than Atheism, 377.

Deity (Notions worthy of the) 207. 233. 250. 293. 298. 305. The same, unworthy, 249. 250. 297, 298.

Dialogues. The Reputation that has been gain’d by writing them, vii. Why they are in Disrepute, ibid.

Dice spoke of to illustrate what Chance is, 306.

Discourse (a) on the social Virtues according to the System of Lord Shaftsbury, from 17 to 43. on Duelling, natural and artificial Courage, from 72 to 97. on the different Effects the same Passions have on Men of different Tempers, from 108 to 113. on Pride and the various Effects and Symptoms of it, from 123 to 131. on the Origin of Politeness, from 132 to 154. on Compliments, Tokens of Respect, Laughing, &c. from 157 to 176. on the Faculty of Thinking, from 178 to 192. on the Sociableness of Man, from 195 to 223. on the Edition: orig; Page: [439]first Motive that could make Savages associate, from 264 to 311. on the second Step to Society, and the Necessity of written Laws, from 311 to 335. on Language, from 336 to 357. on diverse Subjects relating to our Nature, and the Origin of Things, from 357 to 381. on Government, Capacities, and the Motives to Study, on Ministers, Partiality and the Power of Money, to the End.

Docility depends upon the Pliableness of the Parts, 201. Lost if neglected in Youth, 211. The superior Docility in Man in a great measure owing to his remaining young longer than other Creatures, 213.

Edition: current; Page: [364]

Dominion (The Desire of.) All Men are born with it, 229. seen in the Claim of Parents to their Children, ibid.

Dress. The only thing by which Men are judg’d of at Courts, 363.

Drunkenness. How it is judg’d of, xiii, xiv.

Dryades and Hama-Dryades, 236.

Duelling. Men of Honour would be laugh’d at if they scrupled it because it is a Sin, 73. What Considerations are slighted for it, 88, 89. The Usefulness of it, 97.

Duellists. Their Concern chiefly owing to the Struggles between the Fear of Shame and the Fear of Death, 86. Seem to act by Enchantment, 88, 89.

Dying, (the Means of) are all equally the Contrivance of Nature, 284. It is as much requisite to die as it is to be born, 283. Several ways of dying are necessary, 295.

E.

Earth (the) our Species would have overstock’d it if there never had been War, 295.

Education (a refined) teaches no Humility, 49. The most effectual Means to succeed in the Education of Children, 66. Teaches to conceal and not to conquer the Passions, 49. 106. The best Proof for the necessity of a good Education, 355. People may be miserable only for want of Education, 366. The necessity of a Christian Education, 375, 377. A Gentleman’s Education destructive to Christian Humility, xx.

Edition: orig; Page: [440]Eggs in Fish not impregnated by the Male as in other oviparous Animals, 287. The Use of this, ibid.

Envy accounted for, 194.

Epicurus (the Doctrine of) exploded, 371, 373.

Evil. The Cause of it more enquired into than that of Good, 293.

Eunuchs overvalued, 101. no part of the Creation, ibid.

Examination of ones self, 44. 68. 94. 104. xxi.

Exchequer. The wise Regulations of it, 390. In all the Business belonging to it the Constitution does nine parts in ten, 391.

Exclaim. Why all Nations cry Oh! when they exclaim, 170, 171.

Experience of greater Use in procuring good Laws than Genius, 382.

F.

Fable (the) or what is supposed to have occasion’d the first Dialogue, xxiii, xxiv.

Fable of the Bees (the first part of the) quoted, 86. 97. 283. 424. spoke against, 3. 38. 96. 104. Defended, 38. 97. 431. What view the Book ought to be seen in, 98. The Treatment it has had, illustrated by a Simile, 99. Vice is no more encouraged in it than Robbing is in the Beggar’s Opera, iv, v.

Edition: current; Page: [365]

Fall (the) of Man not predestinated, 271.

Fathers of the Church delighted in Acclamations whilst they were preaching, 163.

Fear, the only thing Man brings into the World with him towards Religion, 232. The Epicurean Axiom that Fear made the Gods exploded, 233.

Fees. The Power of them upon Lawyers and Physicians, 27. 430.

Fish. A visible Provision made by Nature for their extraordinary Numbers, 287. The vast Consumption of them, 288.

Flatterers of our Species. Why they confound what is acquired with what is natural, 359, 360, 361.

Flattery. Men of the best Parts not proof against it, 68. The Beginning of it in Society, 153. Becomes less bare-faced as Politeness encreases, 163.

Flies, 290.

Edition: orig; Page: [441]Folly of Infants, 263 [183?].

Fools (learned) where to be met with, 187.

Frailties paum’d upon the World for Virtues, 107.

Friendship, never lasting without Discretion on both Sides, 107.

Frowning describ’d, 169.

Frugality. When it is no Virtue, 112.

Fulvia. The Reason why no Character is given of her, xxiii.

G.

Gassendus is the Example the Author has follow’d in these Dialogues, xxv.

Genius. Many Things are ascrib’d to Genius and Penetration, that are owing to Time and Experience, 149. Has the least Share in making Laws, 386.

Gentleman (a fine) drawn, and the Picture approved of by Horatio, from 51 to 58. Why there are not many such, from 61 to 66.

Gestures made from the same Motive in Infants and Orators, 344. The Abuse of them, ibid. To make use of them more natural than to speak without, 345.

Glory (the Love of) in Men of Resolution and Perseverance may without other Help produce all the Accomplishments Men can be possess’d of, 61, 62. 65. A Tryal to know whether a fine Gentleman acts from Principles of Virtue and Religion, or from Vain-glory, 70, 71. When only the Love of Glory can be commendable, 83. The eager Pursuit of worldly Glory inconsistent with Christianity, xix.

Governing. Nothing requires greater Knowledge than the Art of it, 382. Is built on the Knowledge of human Nature, 384.

Government. Which is the best Form of it, is yet undecided, 208. Is in Bees the Work of Nature, 206. None can subsist without Laws, 315. What the best Forms of it are subject to, 381.

Edition: current; Page: [366]

Government (the) of a large City: What sort of Wisdom it requires, 386. Compared to the knitting Frame, ibid. To a musical Clock, 387. Once put into good Order may go right, tho’ there should not be a wise Man in it, 388.

Edition: orig; Page: [442]Gratitude (Man’s) examined into, as the Cause of Divine Worship, 238. 245, 246.

H.

Happiness on Earth like the Philosophers’ Stone, 197.

Hero’s of Antiquity chiefly famed for subduing of Monsters and wild Beasts, 265.

Honour. The Principle of it extoll’d, 37, 38. 72. The same condemn’d, 73. Is a Chimerical Tyrant, 79. Is the Result of Pride; but the same Cause produces not always the same Effect, 85. Is acquired, and therefore no Passion belonging to any one’s Nature, 86. Is not compatible with the Christian Religion, 93. In Women more difficult to be preserv’d than in Men, 126. Is not founded upon any Principle of Virtue or Religion, 128. The Signification of the Word whimsical, ibid.

Horatio refuses to accept of the Fable of the Bees, 38. Is tax’d with maintaining the Theory of what he cannot prove to be practicable, 39. Owns that the Discourse of Cleomenes had made an Impression upon him, 44. Mistakes Cleomenes and grows angry, 45, 46, 47. Interrupts him, 48. Finds fault again with Cleomenes wrongfully, and seems displeas’d, 58. Sees his Error, begs Pardon, and desires Cleomenes to go on, 60. Takes upon him to be the Fine Gentleman’s Advocate, 70. Labours hard to justify the Necessity of Duelling, 72, 73. 79. Shews the intolerable Consequences of Affronts not resented, ibid. 80. Accepts of the Fable of the Bees, 94. Why he dislikes it, 104. Having consider’d on the Origin of Politeness, pays a Visit to Cleomenes, 175 [157]. Invites him to dinner, 217. Cannot reconcile the Account of Savages with the Bible, 220. Proposes mutual Affection as a Means to make Men associate, 293. Allows of the Conjecture about the first Step towards Society, 307. Comes into the Sentiments of Cleomenes, 430. His Character, xvii, xviii.

Horses, not tame by Nature, 316. What is call’d vicious in them, 317.

Humility (Christian.) No Virtue more scarce, xx.

Hutcheson (Mr.) A Favour ask’d him, 417.

Hypocrisy. To deceive by counterfeiting it, 35. Of some Edition: orig; Page: [443]Divines, 98. Few are never guilty of it, 107. Detected in the Pretences to Content in Poverty, 110, 111. When own’d, 119.

I.

Idiots not affected with Pride, 176. Made by loss of Memory, 192.

Idolatry. All the Extravagancies of it pointed at in the second Commandment, 325. Of the Mexicans, 326.

Edition: current; Page: [367]

Jews knew Truths which the politest Nations were ignorant of 1500 Years after, 249.

Ignorance of the true Deity is the Cause of Superstition, 233. 236. 374.

Indolence not to be confounded with Laziness, 116.

Indolent, easy Man (An.) The difference between him and an active, stirring Man in the same Circumstances, from 108 to 120.

Infants. The Management of them, 183. Why they ought to be talk’d to, 184. 201. Imagine every thing to think and to feel, 235. This folly humour’d in them, 236. Their Crying given them to move Pity, 339. Vent their Anger by Instinct, 351.

Innes (The Reverend Dr.) quoted, xxx. His Sentiments on Charity, xxxi.

Insects would over-run the Earth in two Years time, if none were destroy’d, 289.

Instinct teaches Men the use of their Limbs, 147. Savages to love, and Infants to suck, neither of them thinking on the Design of Nature, 258. All Men are born with an Instinct of Sovereignty, 319. 322. 323.

Invention of Ships, 149, 150. What sort of People are best at Invention, 152, 153. No Stability in the Works of human Invention, 208.

Invisible Cause. (An) How Savages come to fear it, 234. The Perplexity it gives to Men ignorant of the true Deity, 239, 240. The wildest Parents would communicate the Fear of it to their Children, 241. The Consequences of different Opinions about it, ibid. 242.

Judges (who are fit to be) 389.

Judgment (sound) What it consists in, 188. Women are as capable of acquiring it as Men, ibid.

Edition: orig; Page: [444]Justice and Injustice. What Notions a Savage of the first Class would have of it, 223.

Justice. The Administration of it impracticable without written Laws, 315.

Juvenal quoted on Superstition, 325, 326.

K.

Knowledge nor Politeness belong to a Man’s Nature, 363.

Knowing à priori, belongs to God only, 207.

L.

Labour. The usefulness of dividing and subdividing it, 335, 336.

Lampridius quoted, 244.

Language. That of the Eyes is understood by the whole Species, 340. is too significant, ibid. How Language might come into the World from two Savages, 341. Signs and Gestures would not cease after the Invention of Speech, 342. A Conjecture on the Strength and Beauty of the English Language, 346. The Reason for it, 348. Edition: current; Page: [368] Whether French or English be more fit to persuade in, 352. The same things are not beautiful in both Languages, 353. The Intention of opprobrious Language, 394. is an equivalent for fighting, 351.

Laughter. Conjectures on the Rationale of that Action, 168.

Laws. All point at some Frailty or Defect belonging to human Nature, 318. The Necessity of written Laws, 315. The Israelites had Laws before they knew Moses, 319. What the wisest of human Laws are owing to, 382. Laws in all Countries restrain the Usurpation of Parents, 229. Laws of Honour are pretended to be superior to all other, 72. are clashing with the Laws of God, 73. Whether there are false Laws of Honour, 86, 87.

Law-givers. What they have chiefly to consider, 323.

Lawyers. When fit to be Judges, 389.

Leaping. Cunning display’d in it, 147.

Learned Fools. Where to be met with, 186.

Learning. How all sorts of it are kept up, and look’d Edition: orig; Page: [445]into in flourishing Nations, 412, 413, 414. 416. How the most useful Parts of it may be neglected for the most trifling, 415. An Instance of it, 416.

Letters. The Invention of them, the third Step to Society, 315.

Lies. Concerning the invisible Cause, 241.

Life in Creatures. The Analogy between it, and what is perform’d by Engines that raise Water by the help of Fire, 181, 182.

Lion (the) describ’d, 268. What design’d for by Nature, ibid. in Paradise, 269, 270. Not made to be always in Paradise, 271. The Product of hot Countries, 273.

Literature. Most Parents that are able bring up their Sons to it, 413.

Love to their Species is not more in Men, than in other Creatures, 203. 364.

Love. Whether the end of it is the Preservation of our Species, 260. Is little to be depended upon among the ill-bred Vulgar, 364, 365.

Lowdness, a Help to Language, 345.

Lucian, viii.

Lucre. A Cordial in a literal Sense, 429.

M.

Males (more) than Females born of our Species, 299.

Man. In the State of Nature, 134. 137. Every Man likes himself better than he can like any other, 143. No Man can wish to be entirely another, 144. Always seeks after Happiness, 196. Always endeavours to meliorate his Condition, 200. Has no Fondness for his Species beyond other Animals, 203. Has a Prerogative above most Animals in point of Time, 202. Remains young longer than any other Creature, 213. May lose his Sociableness, 214. There can be no civilis’d Man, before there is Civil Society, ibid. Man is born with a Desire after Government, and no Capacity for it, 230. Edition: current; Page: [369] Claims every thing he is concern’d in, 238. 257. Is more inquisitive into the Cause of Evil, than he is into that of Good, 238. Is born with a Desire of Superiority, 254. 311. Has been more mischievous to his Species, than wild Beasts have, 285. What gives us an Insight into the Nature of Man, 315. Edition: orig; Page: [446]Is not naturally inclined to do as he would be done by, 317. Whether he is born with an Inclination to forswear himself, 321. Thinks nothing so much his own as what he has from Nature, 359. The higher his Quality is, the more necessitous he is, 199. Why he can give more ample Demonstrations of his Love than other Creatures, 364. Could not have existed without a Miracle, 371. 378, 379.

Man of War, 149.

Manners (the Doctrine of good) has many Lessons against the outward Appearances of Pride, but none against the Passion itself, 49. What good Manners consists in, 104. Their Beginning in Society, 154. Have nothing to do with Virtue or Religion, 155.

Marlborough (the Duke of) opposite Opinions concerning him, 407, 408. Was an extraordinary Genius, ibid. A Latin Epitaph upon him, 409. The same in English, 410.

Mathematicks of no Use in the curative Part of Physick, 174.

Memory. The total Loss of it makes an Idiot, 192.

Men of very good Sense may be ignorant of their own Frailties, 65, 66. All Men are partial Judges of themselves, 107. All bad that are not taught to be good, 316.

Mexicans. Their Idolatry, 326.

Milton quoted, 269.

Minister (the Prime.) No such Officer belonging to our Constitution, 393. Has Opportunities of knowing more than any other Man, 395. The Stratagems plaid against him, 396. Needs not to be a consummate Statesman, 397. What Capacities he ought to be of, 309 [399]. 401. Prime Ministers not often worse than their Antagonists, 406.

Miracles. What they are, 231. Our Origin inexplicable without them, 371. 378, 379.

Mobs not more wicked than the Beau Monde, 42. In them Pride is often the Cause of Cruelty, 131.

Money to Servants. A short Debate about it, 56, 57.

Money is the Root of all Evil, 421. The Necessity of it in a large Nation, ibid. 422. Will always be the Standard of Worth upon Earth, 423. The Invention of it adapted to human Nature beyond all others, 427. Edition: orig; Page: [447]Nothing is so universally charming as it, 428. Works mechanically on the Spirits, 429, 430.

Montain. A Saying of his, 136.

Moreri censured, 244.

Moses vindicated, 220, 221. 248, 249, 250. 269, 270. 368. 378, 379, 380.

Edition: current; Page: [370]

Motives. The same may produce different Effects, 107. To study and acquire Learning, 412, 413. 417, 418. They are what Actions ought to be judg’d by only, xxi.

N.

Nations. Why all cry Oh! when they exclaim, 170. In large flourishing Nations no sorts of Learning will be neglected, 416.

Natural. Many things are call’d so, that are the Product of Art, 159. How we may imitate the Countenance of a natural Fool, 175. Why it is displeasing to have what is Natural distinguish’d from what is Acquired, 359, 360, &c.

Nature. Not to be follow’d by great Masters in Painting, 11. Great difference between the Works of Art and those of Nature, 207. Nature makes no Tryals or Essays, ibid. What she has contributed to all the Works of Art, 209. She forces several Things upon us mechanically, 170. Her great Wisdom in giving Pride to Man, 192. All Creatures are under her perpetual Tutelage, 257. And have their Appetites of her as well as their Food, 258. 261 Nature seems to have been more sollicitous for the Destruction, than she has been for the Preservation of Individuals, 290. Has made an extraordinary Provision in Fish, to preserve their Species, 287. Her Impartiality, 290. The Usefulness of exposing the Deformity of untaught Nature, 352. She has charged every Individual with the Care of itself, 418.

Nature (human) is always the same, 163. The Complaints that are made against it are likewise the same every where, 317. The Selfishness of it is visible in the Decalogue, 318. 320.

Noah, 220 An Objection started concerning his Descendants, 221.

Edition: orig; Page: [448]Noise made to a Man’s Honour is never shocking to him, 164. Of Servants, why displeasing, 167.

O.

Oaths. What is requisite to make them useful in Society, 313.

Obedience (human) owing to Parents, 331.

Objection (an) to the Manner of managing these Dialogues, xxiv.

Opera’s extravagantly commended, 12, 13, &c. Compared to Bear-gardens, 41.

Opera (Beggar’s) injuriously censured, iv.

Opinions. The Absurdity of them in Sacred Matters, 243. How People of the same Kingdom differ in Opinion about their Chiefs, 407.

Origin (the) of Politeness, from 132 to 154. Of Society, 226. 263. Of all Things, 371, 372, 373. The most probable Account of our Origin, 378, 379.

Ornaments bespeak the Value we have for the Things adorned, 362. What makes Men unwilling to have them seen separately, 363.

P.

Edition: current; Page: [371]

Pain. Limited in this Life, 285.

Painters, blamed for being too natural, 10.

Painting. How the people of the Grand Gout judge of it, 5, 6. &c.

Paradise. The State of it miraculous, 269, 370.

Parents. The Unreasonableness of them, 229. 257. Compared to inanimate Utensils, 261, 262. Why to be honoured, 330. The Benefit we receive from them, 331.

Partiality is a general Frailty, 406, 407.

Passion. What it is to play that of Pride against itself, 67, 129. 132. How to account for the Passions, 193.

Personages introduced in Dialogues. The Danger there is in imitating the Ancients in the Choice of them, viii. Caution of the Moderns concerning them, ibid. When they are displeasing, ix. It is best to know something of them beforehand, x.

Edition: orig; Page: [449]Philalethes, an invincible Champion, viii [ix].

Physician (the social) 24. Physicians are ignorant of the constituent Parts of Things, 174.

Physick. Mathematicks of no use in it, 174.

Places of Honour and Trust. What Persons they ought to be flll’d with, 388, 389.

Plagues. The Fatality of them, 281.

Plato. His great Capacity in writing Dialogues, vii, viii.

Pleas, and Excuses of worldly Men, xviii, xix.

Politician. His chief Business, 385.

Politeness expos’d. 97. 104. xix. The Use of it, 131, 132. The Seeds of it lodg’d in Self-Love, and Self-liking, 138. How it is produc’d from Pride, 145. A Philosophical Reason for it, 146.

Polite (a) Preacher. What he is to avoid, xi.

Poor. (the) Which sort of them are most useful to others, and happy in themselves; and which are the reverse, 424. The Consequence of forcing Education upon their Children, 426, 427.

Popes. What is chiefly minded in the Choice of them, 35.

Poverty (voluntary) very scarce, 113. The only Man in Antiquity that can be said to have embraced it, ibid. The greatest Hardship in Poverty, 115.

Predestination. An inexplicable Mystery, 271. 292.

Preferment. What Men are most like to get it, 418, 419.

Pride. The Power of it, 47, 48. No Precepts against it in a refined Education, 49. Encreases in proportion with the Sense of Shame, 66. What is meant by playing the Passion of Pride against itself, 67. Is able to blind the Understanding in Men of Sense, 68. Is the Cause of Honour, 85. Pride is most enjoy’d when it is well hid, 96. Why more predominant in some than it is in others, 123, 124. Whether Women have a greater Share of it than Men, 125. Why more encourag’d in Women, 126. The natural and artificial Edition: current; Page: [372] Symptoms of it, 129, 130. Why the artificial are more excusable, ibid. In whom the Passion is most troublesome, 131. To whom it is most easy to stifle it, ibid. In what Creatures it is most conspicuous, 135. The Disguises of it, 141. Who will learn to conceal it soonest, 148. Is our most dangerous Enemy, 352.

Principle. A Man of Honour, and one that has none, may act from the same Principle, 83. Reasons why Edition: orig; Page: [450]the Principle of Self-esteem is to be reckon’d among the Passions, 84, 85. Honour not built upon any Principle, either of Virtue or Religion, 128. Principles most Men act from, 417, 418.

Proposal (a) of a Reverend Divine for an human Sacrifice, to compleat the Solemnity of a Birth-Day, xxxi.

Providence saved our Species from being destroy’d by wild Beasts, 272. 282. A Definition of it, 275. The raising of Cities and Nations, the Work of Providence, 384.

Prudence, 324.

Purposes. Fire and Water are made for many that are very different from one another, 282 [283].

Q.

Qualifications. The most valuable in the Beginning of Society, would be Strength, Agility, and Courage, 311.

Quarrels. How to prevent them, 71. The Cause of them on account of Religion, 241. Occasion’d by the Word Predestination, 271. A Quarrel between two learned Divines, 416.

R.

Reason is acquired, 212. The Art of Reasoning not brought to perfection in many Ages, 248, 249. The Stress Men lay upon their Reason is hurtful to Faith, 375. xvi.

Religion (the Christian) the only solid Principle, 98. 376. Came into the World by Miracle, 231. What was not reveal’d, is not worthy to be call’d Religion, 232. The first Propensity toward Religion, not from Gratitude in Savages, 237, 238.

Reneau (Monsieur) accounts mechanically for the sailing and working of Ships, 150, 151.

Respect. Whether better shewn by Silence or by making a Noise, 166, 167.

Revenge. What it shews in our Nature, 322.

Reverence. The Ingredients of it, 226. Illustrated from the Decalogue, 328. The Weight of it to procure Obedience, 330.

Riches. The Contempt of them very scarce, 113. Lavishness no Sign of it, ibid. Are the necessary Support of Honour.

Edition: orig; Page: [451]Ridicule. The Lord Shaftsbury’s Opinion concerning it, 32.

Right (the) which Parents claim to their Children, is unreasonable, 229. 252 [255].

Edition: current; Page: [373]

Right and Wrong. The Notions of it acquired, 251, 252. 254.

Roman Catholicks are no Subjects to be relied upon, but in the Dominions of his Holiness, 92.

Rome (the Court of) the greatest Academy of refin’d Politicks, 34. Has little Regard for Religion or Piety, 35.

Rule (a) to know what is natural, from what is acquired, 358.

S.

Sabbath. (the) The Usefulness of it in worldly Affairs, 333, 334.

Savages of the first Class are not to be made sociable when grown up, 137. It would require many Ages to make a polite Nation from Savages, 137, 138. The Descendants of civilis’d Men may degenerate into Savages, 220. 309. There are Savages in many Parts of the World, 224. Savages do all the same Things, 335. Those of the first Class could have no Language, 336. nor imagine they wanted it, 337. Are incapable of learning any when full grown, 338.

Savage (a) of the first Class of Wildness, would take every thing to be his own, 223. Be incapable of governing his Off-spring, 225. 227. Would create Reverence in his Child, 226. Would want Conduct, 228. Could only worship an invisible Cause out of Fear, 234. Could have no Notions of Right and Wrong, 252. Propagates his Species by Instinct, 258. Contributes nothing to the Existence of his Children as a voluntary Agent, 261. The Children of his bringing-up would be all fit for Society, 264.

Scheme (the) of Deformity. The System of the Fable of the Bees so call’d by Horatio, 2. 5.

Scheme (the) or Plan of this Globe, requires the Destruction, as well as the Generation of Animals, 283. Mutual Affection in our Species would have been destructive to it, 296 &c.

Edition: orig; Page: [452]Scolding, and calling Names, bespeak some degree of Politeness, 350. The Practice of it could not have been introduced without Self-denial at first, 351.

Security of the Nation. What a great Part of it consists in, 403.

Self-liking different from Self-love, 134. Given by Nature for Self-preservation, ibid. The Effect it has upon Creatures, 135. 141. Is the Cause of Pride, 136. What Creatures don’t shew it, ibid. What Benefit Creatures receive from Self-liking, 139. Is the Cause of many Evils, ibid. Encomiums upon it, 141, 142. Suicide impracticable whilst Self-liking lasts, ibid.

Selfishness (the) of human Nature, visible in the Ten Commandments, 318, 320.

Self-love the Cause of Suicide, 142. Hates to see what is Acquired separated from what is Natural, 359, 360, 361.

Services (reciprocal) are what Society consists in, 421. Are impracticable without Money, 422, 423.

Shaftsbury (the Lord) Remarks upon him. For jesting with Reveal’d Edition: current; Page: [374] Religion, 24. 432. For holding Joke and Banter to be the best and surest Touchstone, to try the Worth of Things by, 32. For pretending to try the Scriptures by that Test, ibid. Was the first who held that Virtue required no Self-denial, 105. Encomiums on him, 32. 431, 432.

Shame is a real Passion in our Nature, 90. The Struggle between the Fear of it, and that of Death, is the Cause of the great Concern of Men of Honour in the Affair of Duelling, 86. 90. The same Fear of Shame that may produce the most worthy Actions, may be the Cause of the most heinous Crimes, 127.

Shame. (the Sense of) The Use that is made of it in the Education of Children, 66. Is not to be augmented without encreasing Pride, ibid.

Ships are the Contrivance of many Ages, 149. Who has given the rationale of working and steering them, 150, 151.

Simile (a) to illustrate the Treatment that has been given to the Fable of the Bees, 99. Applied, 103.

Sighing describ’d, 169.

Signs and Gestures. The Significancy of them, 339. Confirm Words, [453] 343. Would not be left off after the Edition: orig; Page: [453]Invention of Speech, 342. Added to Words are more persuading than Speech alone, 344.

Sociableness. The Love of our Species not the Cause of it, 195. 202. Erroneous Opinions about it, 196, 197, 198. Reasons commonly given for Man’s Sociableness, 199. Great part of Man’s Sociableness is lost, if neglected in his Youth, 201. What it consists in, 204, 205. 209. The Principle of it is the work of Providence, 206. Mutual Commerce is to Man’s Sociableness what Fermentation is to the Vinosity of Wine, 210, 211. Sociableness in a great measure owing to Parents, 331.

Social System. The manner of it in judging of State-Ministers and Politicians, 17. Of the Piety of Princes, 18. Of Foreign Wars, 19. Of Luxury, ibid.

Social Virtue, according to the System of Lord Shaftsbury, discovered in a Poor Woman who binds her Son Prentice to a Chimneysweeper, 20. in Lawyers and Physicians, 24. in Clergymen, 25. is of little use unless the Poor and meaner sort of People can be possess’d of it, 28, 29.

Social Toyman (the) describ’d, 30, 31.

Society, (civil) Cautions to be used in judging of Man’s Fitness for Society, from 195 to 204. is of human Invention, 205. Man is made for it as Grapes are for Wine, ibid. 206. what Man’s Fitness for it consists in, 209. might arise from private Families of Savages, 214. 224. Difficulties that would hinder Savages from it, 225. 227, 228. 263. The first step toward it would be their common danger from wild Beasts, 264. The second step would be the danger they would be in from one another, 311. The third and last would be the Invention of Letters, 315. Civil Society is built upon the Edition: current; Page: [375] Variety of our Wants, 421. Temporal Happiness is in all large Societies as well to be obtain’d without Speech, as without Money, 423.

Sommona-codom, 379.

Soul (the) compared to an Architect, 178. We know little of it that is not reveal’d to us, 182.

Species, (our) the high Opinion we have of it, hurtful, xvi.

Speech, tho’ a Characteristick of our Species, must be taught, 212. is not to be learn’d by People come to Maturity, if till then they never had heard any, 213, 338. The want of it easily supply’d by Signs among Edition: orig; Page: [454]two Savages of the first Class, 339. Whether invented to make our Thoughts known to one another, 342. The first Design of it was to persuade, 343. Lowness of Speech a piece of good Manners, 346. The Effect it has, 348.

Spinosism, 373.

Statesman (a consummate) what he ought to be, 397, 398. The scarcity of those who deserve that Name, 411.

Study (hard) whether Men submit to it to serve their Country or themselves, 417, 418. 420.

Sun (the) not made for this Globe only, 282.

Superiority of Understanding in Man, when most visibly useful, 357. when disadvantageous, 358.

Superstition. The Objects of it, 325, 326. What sort of People are most in danger of falling into it, 374.

Superstitious Men may blaspheme, 377.

Symptoms of Pride, natural and artificial, 129, 130.

System, (the) that Virtue requires no Self-denial is dangerous, 106. The reason, ibid.

T.

Tears. Drawn from us from different Causes, 172.

Temple (Sir William) animadverted upon, 214. 222. A long Quotation from him, 215, 216.

Tennis-play spoke of to illustrate what Chance is, 306.

Thinking. Where perform’d, 178. What it consists in, 179. 183. Immense difference in the Faculty of it, 185. Acquired by Time and Practice, 212.

Thought operates upon the Body, 177.

Time. Great difficulty in the division of it, 333. The Sabbath a considerable help in it, 334.

Treasurer (the Lord) when he obeys at his Peril, 392.

Treasury. What the Management of it requires, 390, 391.

Truth. Impertinent in the sublime, 5. not to be minded in Painting, 9.

V.

Vanity may be own’d by modest Men, v, vi.

Vice has the same Origin in Man that it has in Horses, 317. Why the Edition: current; Page: [376] Vices of particular Men may be said to belong to the whole Species, 323. Vice is exposed in Edition: orig; Page: [455] the Fable of the Bees, v. What it consists in, vi. Why bare-faced Vice is odious, xiii.

Virtue, in the Sense of the Beau Monde, imbibed at Opera’s, 15. What most of the Beau Monde mean by it, xii. Real Virtue not more to be found at Opera’s than at Bear-gardens, 41, 42. A Tryal, whether a fine Gentleman acts from Principles of Virtue and Religion, or from Vain-glory, 70, 71. It requires Self-denial, 106. False Pretences to Virtue, 108, 109. 118. No Virtue more often counterfeited than Charity, 120. Virtue is not the Principle from which Men attain to great Accomplishments, 412. 419, 420. is the most valuable Treasure, 421. yet seldom heartily embraced without Reward, ibid. No Virtue more scarce than Christian Humility, xx.

Virtuous. When the Epithet is improper, 106. Actions are call’d virtuous that are manifestly the Result of Frailties, 107. There are virtuous Men; but not so many as is imagin’d, 405.

Vitzliputzli. Idol of the Mexicans, 326.

Unity (the) of a God, a Mystery taught by Moses, 248. disputed and denied by the greatest Men in Rome, 249.

Understanding (Man’s superiour) has defeated the Rage of wild Beasts, 272. when found most useful, 357. disadvantageous in Savages, 358.

W.

Wars. The Cause of them, 294. What would have been the Consequence if there never had been any, 295. 301, 302.

Watches and Clocks. The Cause of the Plenty as well as Exactness of them, 336.

Weeping. A Sign of Joy as well as Sorrow, 171. A Conjecture on the Cause of it, 172.

Whales. Their Food, 289. Why the Oeconomy in them different from other Fish, ibid.

Wild Beasts. The danger from them the first step toward Society, 264. always to be apprehended whilst Societies are not well settled, ibid. 265. 275, 276. 309, 310. Why our Species was never totally extirpated by them, 273, 274. 277, 278, 279. The many Mischiefs our Species has sustain’d from them, 265. 271. 274. 279. 281. Have Edition: orig; Page: [456]never been so fatal to any Society of Men as often Plagues have, 281. Have not been so calamitous to our Species as Man himself, 285. are part of the Punishment after the Fall, 308. Range now in many Places where once they were routed out, 309. Our Species will never be wholly free from the danger of them, ibid.

Wild Boars. Few large Forests without in temperate Climates, 276. Great Renown has been obtain’d by killing them, ibid.

Edition: current; Page: [377]

Will (the) is sway’d by our Passions, 262.

Wisdom (the divine) very remarkable in the contrivance of our Machines, 173. 230. in the different Instincts of Creatures, 273. 282. in the second Commandment, 324. Acts with original Certainty, 201 [207]. Becomes still more conspicuous as our Knowledge encreases, 233. 380. Wisdom must be antecedent to the things contriv’d by it, 373.

Wolves only dreadful in hard Winters, 279.

Woman (a Savage) of the first Class would not be able to guess at the Cause of her Pregnancy, 259.

Women are equal to Men in the Faculty of Thinking, 188. Excell them in the Structure of the Brain, 189. What Blessing the Scarcity of them would deprive Society of, 302.

Works of Art lame and imperfect, 207.

Worship (Divine) has oftener been perform’d out of Fear than out of Gratitude, 237. 244, 245.

Wrongheads, who think Vice encouraged when they see it exposed, v.

Y.

Youth. A great part of Man’s Sociableness owing to the long continuance of it, 213.

Z.

Zeuxis, 10.

F I N I S.

References to Mandeville’s Work.

References to Mandeville’s Work.

A LIST CHRONOLOGICALLY ARRANGED of references to MANDEVILLE’S WORK

THIS is not intended to be a complete list. Only such references have been recorded as from contemporaneousness, representativeness, astuteness, or the importance of their author are of some interest. Purely biographical references are not noted. Although later editions are often referred to, works are listed under the date of the earliest edition to include the indicated reference to Mandeville. Certain works are placed, proper indication being made, not under date of first publication, but under date of composition. Capitalization in titles has been standardized. Dates of editions have uniformly been expressed in arabic numerals.

[1716]COWPER, Mary, Countess. Diary of Mary Countess Cowper, Lady of the Bedchamber to the Princess of Wales 1714–1720. 1864.

‘Mr. Horneck, who wrote The High German Doctor. … told me that Sir Richard Steele had no Hand in writing the Town Talk, which was attributed to him; that it was one Dr. Mandeville and an Apothecary of his Acquaintance that wrote that Paper; and that some Passages were wrote on purpose to make believe it was Sir R. Steele’ (see under date of 1 Feb. 1716). There seem no grounds for this assertion.

[1722]MEMOIRES HISTORIQUES ET CRITIQUES. Amsterdam. 1722. [Periodical]

See pp. 45–54 (July) for fair-minded review of Pensées Libres: ‘… il raisonne clairement et solidement, mais il faut avoüer aussi, qu’il n’est pas toûjours heureux dans les applications qu’il fait. … Son premier chapitre, où il traitte de la religion en general, est magnifiquement bien conçu. … Rien de plus grand, rien de plus vrai que ce qu’il en pense’ (p. 46). ‘… de politesse, de précision et de vivacité [of the style]. … Ces sortes de vivacité … ne font jamais honneur à un Autheur Chretien’ (p. 54).

Edition: current; Page: [419]

EVENING POST. [Periodical][1723]

The issue of 11 July contained the Grand Jury’s presentment of the Fable; see Fable i. 383–6.

FORTGESETZTE SAMMLUNG VON ALTEN UND NEUEN THEOLOGISCHEN SACHEN. Leipsic. 1723. [Periodical] [Also known as Unschuldige Nachrichten.]

See pp. 751–3 for review of French version of Free Thoughts.

LONDON JOURNAL. 27 July 1723. [Periodical]

The ‘abusive’ letter to Lord C. against Mandeville, signed Theophilus Philo-Britannus. It is reprinted in Fable i. 386–401.

MAENDELYKE UITTREKSELS, of Boekzael der Geleerde Werelt. Amsterdam. 1723. [Periodical]

See xvi. 688–714, xvii. 71–96 and 152–72 for reviews of the French and Dutch translations of the Free Thoughts.

NEUER ZEITUNGEN VON GELEHRTEN SACHEN. Leipsic. 1723. [Periodical]

See pp. 252–3 for complimentary notice of the French translation of the Free Thoughts.

PASQUIN. 13 May 1723. [Periodical]

Contains the earliest reference which I know to the Fable.

‘I am obliged to a Book, intitled, The Fable of the Bees, or private Vices publick Benefits, for another good Argument in Defence of my Clients in this particular, which is contained in this following Paradox, (viz.) That if every Body paid his Debts honestly, a great many honest Men would be ruined: For, as it is learnedly argued in the aforesaid Book, that we are indebted to particular, private Vices for the flourishing Condition and Welfare of the Publick;. and as, if Luxury ceased, great part of our Commerce would cease with it; and if the Reformation of Manners should so far prevail as to abolish Fornication, Multitudes of Surgeons would be ruined; so, if every Body should grow honest and pay his Debts willingly, what would become of the long Robe and Westminster-hall?’

BARNES, W. G. Charity and Charity Schools Defended. A Sermon Preach’d at St. Martin’s Palace, in Norwich, on March 6. 1723 [1724]. By the Appointment of the Right Reverend Father in God, Thomas Late Lord Bishop of that Diocese: and since at St. Mary’s in White-Chapel. 1727.[1724]

This sermon attacks ‘Cato’s’ ‘Letter’ on charity-schools, and the Fable as being representative of the arguments against these schools.

COLERUS.

A review of Mandeville’s Free Thoughts, in the Auserlesene Theologische Bibliothec i. 515. [This attack is cited from Lilienthal’s Theologische Bibliothec (1741), pp. 327–8. The Neuer Zeitungen von Gelehrten Sachen for 1724 refers to parts 5 and 6 of the Auserlesene Theologische Bibliothec for a consideration of the French translation of the Free Thoughts. Walch’s Bibliotheca Theologica (1757–65) i. 762, n., mentions a review of the Free Thoughts in the Auserlesene Theologische Bibliothec i. 379 and 489. I have been unable to secure this work to check up these references.]

Edition: current; Page: [420]

DENNIS, John. Vice and Luxury Publick Mischiefs: or, Remarks on a Book intituled, the Fable of the Bees. 1724.

See above, ii. 407–9.

FIDDES, Richard. A General Treatise of Morality, Form’d upon the Principles of Natural Reason Only. With a Preface in Answer to Two Essays lately Published in the Fable of the Bees. 1724.

See above, ii. 406–7.

[HAYWOOD, Eliza.] The Tea-Table. [Periodical]

See no. 25, for 15 May 1724: ‘… I have a very high Opinion of this Author’s Parts. … I am very far from endeavouring to refute what he therein [in the Fable] advances, I am too sensible that is not so easily done. I would only intreat the Author to consider … whether the propagating such Opinions as these, can possibly be of any Benefit … but whether, on the contrary, they are not likely to do a great deal of Mischief, which I … believe the Author was very far from intending’ (p. [2]).

[HUTCHESON, Francis.] A letter, signed Philanthropos, ‘To the Author of the London Journal’, published in two parts in that paper on 14 and 21 Nov. 1724.

This letter announces and anticipates the Inquiry into the Original of our Ideas of Beauty and Virtue, noticed below under year 1725.

LAW, William. Remarks upon a Late Book, entituled, the Fable of the Bees. … In a Letter to the Author. To which is added, a Postscript, containing an Observation or Two upon Mr. Bayle. 1724. See above, ii. 401–6.

LÖSCHER, V. Nötige Reflexiones über das im Jahr 1722 zum Vorschein gebrachte Buch Pensées libres sur la religion etc. oder freye Gedanken von der Religion, nebst wohlgemeinter Warnung vor dergleichen Büchern abgefasst von Valentin Ernst Löschern D. Oberkonsistoriali und Superintendenten zu Dressden. 1724. [Cited from Sakmann, Bernard de Mandeville, p. 214.]

NEUER ZEITUNGEN VON GELEHRTEN SACHEN. Leipsic. 1724. [Periodical]

See pp. 840–1, 982–3, and 1060 for notice of French translation of Free Thoughts.

[THOMASIUS, Christian.] Vernünfftige und christliche aber nicht scheinheilige Thomasische Gedancken und Erinnerungen über allerhand gemischte philosophische und juristische Händel. Andrer Theil. Halle. 1724.

See pp. 686 and 688–90. This is more a review of Löscher’s Nötige Reflexiones than of the Free Thoughts.

THE WEEKLY JOURNAL OR SATURDAY’S-POST [MIST’S]. [Periodical]

See issue of 5 Aug. 1724, for attack: ‘… a Composition of Dulness and Wickedness, as even this extraordinary Age has not produced before.’

Edition: current; Page: [421]

[WILSON], Thomas, Bishop of Sodor and Man. The True Christian Method of Educating the Children both of the Poor and Rich, Recommended more especially to the Masters and Mistresses of the Charity-Schools, in a Sermon Preach’d in the Parish-Church of St. Sepulchre, May 28, 1724. 1724.

See pp. 11–12.

BIBLIOTHEQUE ANGLOISE, ou Histoire Litteraire de la Grande[1725]

Bretagne, par Armand de la Chapelle. Amsterdam. [Periodical]

See xiii. 97–125 (review of the Fable) and 197–225 (review of Bluet’s Enquiry). ‘Assurément le dessein ne sauroit être plus mauvais’ (xiii. 99). ‘Le luxe, comme on le sait, est un de ces vices qui paroissent les moins odieux, parce qu’il est un des plus sociables, et c’est apparemment pour cette raison que l’auteur de la Fable l’a choisi, comme par préference sur tous les autres, pour en tirer sa conclusion générale’ (xiii. 206).

[BLUET, George.] An Enquiry whether a General Practice of Virtue tends to the Wealth or Poverty, Benefit or Disadvantage of a People? In which the Pleas … of the Fable of the Bees … are considered. 1725.

See above, ii. 410–12.

FORTGESETZTE SAMMLUNG VON ALTEN UND NEUEN THEOLOGISCHEN SACHEN. Leipsic. 1725. [Periodical] [Also known as Unschuldige Nachrichten.]

See pp. 516–20 for review of V. E. Löscher’s ‘Nöthige Reflexions über die Pensées libres’, Wittenberg, 1724. ‘Diese gottlosen Pensées …’ (p. 516).

HENDLEY, William. A Defence of the Charity-Schools. Wherein the Many False, Scandalous and Malicious Objections of those Advocates for Ignorance and Irreligion, the Author of the Fable of the Bees, and Cato’s Letter in the British Journal, June 15. 1723. are fully and distinctly answer’d; and the Usefulness and Excellency of Such Schools clearly set forth. To which is added by Way of Appendix, the Presentment of the Grand Jury of the British Journal, at their Meeting at Westminster, July 3. 1723. 1725.

See above, i. 14, n. 1.

[HUTCHESON, Francis.] An Inquiry into the Original of our Ideas of Beauty and Virtue; in Two Treatises. In which the Principles of … Shaftesbury are … defended against … the Fable of the Bees. 1725.

Announced as ‘On Monday next will be publish’d’, in the Post-Boy for 25–27 Feb. 172 4/5. See above, ii. 420, under Hutcheson, and ii. 345, n. 1.

NEUER ZEITUNGEN VON GELEHRTEN SACHEN. Leipsic. [Periodical]

See pp. 838–43 for review of Fable, and pp. 847–50 for a notice of Bluet’s Enquiry cited from the Bibliothèque Angloise of this same year.

Edition: current; Page: [422]

[1726]ALOGIST, Isaac (pseudonym). Three Letters to the Dublin Journal, published therein on 10 and 17 Sept. and 22 Oct. 1726. They were reprinted in A Collection of Letters and Essays … Publish’d in the Dublin Journal, ed. Arbuckle, ii. 181–200 and 239–50.

‘All the Papers subscribed Isaac Alogist’, says Arbuckle (ii. 429), ‘came to me from a Gentleman, who will not so much as permit me to enquire after him, far less to publish his Name.’

FORTGESETZTE SAMMLUNG VON ALTEN UND NEUEN THEOLOGISCHEN SACHEN. Leipsic. 1726. [Periodical] [Also known as Unschuldige Nachrichten.]

See pp. 841–3 for derogatory review of the German version of the Free Thoughts.

[HUTCHESON, Francis.] Three Letters to the Dublin Journal, published therein on 5, 12, and 19 Feb. 1726. These three letters make up the last half of Hutcheson’s Reflections upon Laughter, and Remarks upon the Fable of the Bees, 1750. They were reprinted in A Collection of Letters and Essays on Several Subjects, lately Publish’d in the Dublin Journal, ed. Arbuckle, also known as Hibernicus’ Letters (1729) i. 370–407.

JOURNAL DES SÇAVANS, … Augmenté de Divers Articles qui ne se trouvent point dans l’Edition de Paris. Amsterdam. 1726. [Periodical]

See lxxviii. 465–73 for a review—unfavourable to Mandeville—of Bluet’s answer to Mandeville.

NEUER ZEITUNGEN VON GELEHRTEN SACHEN. Leipsic. 1726. [Periodical]

See p. 510 for an excerpt from the review in the Journal des Sçavans of Bluet’s reply.

REIMARUS, H. S. Programma quo Fabulam de Apibus examinat simulque ad Orationes IV. de Religionis et Probitatis in Republica Commodis ex Legato Peterseniano a Qvatuor Alumnis Classis Primae ad D.V. Sept. hor. IX matut. habendas Literarum Patronos O. O. Observanter invitat. M. Hermannus Samuel Reimarus. Lcy. Wism. Rect. Wismariae. Typis Zanderianis. [1726.]

[Cited from Sakmann, Bernard de Mandeville, p. 212.]

THOROLD, John. A Short Examination of the Notions Advanc’d in a (Late) Book, intituled, the Fable of the Bees or Private Vices, Publick Benefits. 1726.

THE TRUE MEANING OF THE FABLE OF THE BEES; in a Letter to the Author of a Book entitled an Enquiry whether a General Practice of Virtue …? Shewing that he has manifestly mistaken the True Meaning of the Fable of the Bees. 1726.

Concerning the mistaken attribution of this work to Mandeville, see my ‘Writings of Bernard Mandeville’, in the Journal of English and Germanic Philology for 1921, xx. 463–4.

Edition: current; Page: [423]

[ARBUCKLE, James.] A Collection of Letters and Essays on Several[1727] Subjects, lately Publish’d in the Dublin Journal. 2 vol. Dublin. 1729.

See ii. 429. First published in the Dublin Journal for 25 March 1727.

MOSHEIM, Joh. Lor. Heilige Reden u̔ber wichtige Wahrheiten der Lehren Jesu Christi. Zweyter Theil. Hamburg. 1727.

[This title is cited from the Neuer Zeitungen von Gelehrten Sachen (1727), p. 796, which mentions it as dealing with the Fable. Vogt’s Catalogus Historico-Criticus Librorum Rariorum (1747), p. 276, also mentions Mosheim’s book in this connexion.]

NEUER ZEITUNGEN VON GELEHRTEN SACHEN. Leipsic. 1727. [Periodical]

See pp. 796–7 for attribution of the Fable to Jakob Masse.

CHANDLER, Sam. Doing Good Recommended from the Example of Christ. A Sermon Preach’d for the Benefit of the Charity-School in Gravel-Lane, Southwark, January 172 7/8. To which is added, an Answer to an Essay on Charity-Schools, by the Author of the Fable of the Bees. 1728.[1728]

Summarized in Sakmann, Bernard de Mandeville, p. 200. The exact date of the sermon was 1 Jan.; see Isaac Watts, Works (1812) vi. 9, n.

DAILY JOURNAL. [Periodical]

The issue of 11 March contained the advertisement of Innes’s book mentioned in Fable ii. 23–4.

[GIBSON, Edmund.] The Bishop of London’s Pastoral Letter to the People of his Diocese. … Occasion’d by Some Late Writings in Favour of Infidelity. 1728.

See p. 2.

GRAND JURY’S PRESENTMENT.

This second presentment of the Fable is reprinted in Remarks upon Two Late Presentments (1729), pp. 3–6 (cf. above, i. 13, n. 1).

INNES, Alexander. ΑΡΕΤΗ-ΛΟΓΙΑ or, an Enquiry into the Original of Moral Virtue. 1728.

See Fable ii. 24–8 and below, ii. 426, under Campbell.

THE LONDON EVENING POST. [Periodical]

The issues of 9 March and 16–19 March (p. 4) contained the advertisement of Innes’s book mentioned in Fable ii. 23–4.

THE PRESENT STATE OF THE REPUBLICK OF LETTERS. 1728. [Periodical]

See ii. 462 (December) for notice and description (in the tone of an advertisement) of Part II of the Fable.

WATTS, Isaac. An Essay towards the Encouragement of Charity Schools, particularly those … supported by Protestant Dissenters. 1728.

This is an elaboration of a sermon preached in Nov. 1727 against the Fable and other attacks on charity-schools.

Edition: current; Page: [424]

WHITEHALL EVENING POST. [Periodical]

The issue of 21–3 March (p. 4) contained the advertisement of Innes’s book mentioned in Fable ii. 23–4.

[1729]BIBLIOTHEQUE RAISONNÉE des Ouvrages des Savans de l’Europe. Amsterdam. 1729. [Periodical]

See viii. 402–45 for review of both parts of the Fable: ‘Les endroits où il prétend accorder la Raison & la Revelation sont ceux qui nous paroissent les plus foibles du second Volume; les raisonnemens qu’il fait sur ce sujet sont si extraordinaires que s’ils avoient le moindre sens on seroit tenté d’y en chercher encore un autre’ (viii. 445).

BYROM, John. The Private Journals and Literary Remains. … Edited by Richard Parkinson. (Chetham Society, vol. 32, 34, 40, 44.) 1824–7.

Cf. above, i. xxviii, n. 1.

THE LONDON JOURNAL. 7 and 14 June 1729. [Periodical]

Both these issues contain several columns attacking the Fable.

NEUER ZEITUNGEN VON GELEHRTEN SACHEN. Leipsic. 1729. [Periodical]

See p. 98 for notice of Innes’s reply.

[1731]THE GENTLEMAN’S MAGAZINE: or, Monthly Intelligencer for the Year 1731. [Periodical]

See p. 118.

READ’S WEEKLY JOURNAL, or BRITISH-GAZETTEER. 27 March 1731. [Periodical]

Contains attack on Fable.

REIMMANN, Jacob Friedrich. Catalogus Bibliothecæ Theologicæ, Systematico-Criticus, in quo, Libri Theologici, in Bibliotheca Reimanniana Extantes, Editi & Inediti, in Certas Classes Digesti, qua fieri potuit Solertia, enumerantur. Hildesheim. 1731.

See pp. 1066–7 for notice of Free Thoughts.

[1732]BERKELEY, George. Alciphron: or, the Minute Philosopher. In Seven Dialogues. Containing an Apology for the Christian Religion, against those who are called Free-Thinkers. 2 vol. 1732.

See above, ii. 412–14.

BIBLIOTHEQUE RAISONNÉE des Ouvrages des Savans de l’Europe. Amsterdam. 1732. [Periodical]

See viii. 227 for notice of the Origin of Honour, and ix. 232 for notice of the Letter to Dion.

THE CHARACTER OF THE TIMES DELINEATED. … Design’d for the Use of those who … are convinc’d, by Sad Experience, that Private Vices are Publick and Real Mischiefs. 1732.

A general jeremiad rather than an attack on Mandeville.

- And, if GOD-MAN Vice to abolish came,

- Who Vice commends, MAN-DEVIL be his Name (p. 10).

Edition: current; Page: [425]

CLARKE, Dr. A. A letter to Mrs. Clayton from Winchester, dated 22 April 1732, in which Dr. Clarke gives his opinion and a one-page summary of the Origin of Honour [in Sundon, Memoirs (1848) ii. 110–11].

Cf. above, i. xxvii, n.

THE CRAFTSMAN. By Caleb D’Anvers, of Gray’s-Inn, Esq. Vol. IX. 1737. [Periodical]

This contains letters (pp. 1–6 and 154–6) against the Fable, addressed to Caleb D’Anvers, in the issues for 29 Jan. and 24 June 1732. One of the letters is mentioned in Mandeville’s Letter to Dion, p. 6.

THE GENTLEMAN’S MAGAZINE: or, Monthly Intelligencer. 1732. [Periodical]

See ii. 687 for citation of an attack on the Fable in Read’s Weekly Journal for 1 April.

[HERVEY, John, Lord.] Some Remarks on the Minute Philosopher. In a Letter from a Country Clergyman to his Friend in London. 1732.

See above, ii. 412.

INDEX EXPURGATORIUS.

The French version of the Free Thoughts was damned by decree of 21 Jan. 1732 (Index Librorum Prohibitorum … Pii Sexti, ed. 1806, p. 112).

JOURNAL HISTORIQUE DE LA REPUBLIQUE DES LETTRES. Leyden. 1732. [Periodical]

See i. 420 for brief review of Letter to Dion.

MOYNE, Abraham LE. Preservatif contre l’Incredulité & le Libertinage en Trois Lettres Pastorales de Monseigneur l’Eveque de Londres. The Hague. 1732. [Title cited from Freytag, Analecta Litteraria (1750), p. 330. Reusch’s Index der verbotenen Bücher (ed. 1883–5, ii. 865, n. 2) also mentions this translation.]

Only the first pastoral letter refers specifically to the Fable. For notice of the pastoral letters here translated, see in this bibliography under Edmund Gibson in the year 1728.

NOVA ACTA ERUDITORUM. Leipsic. 1732. [Periodical]

See pp 212–23 in the May issue for mention of Innes’s reply to Mandeville: the APETH-7?∍3!.

POPE, alexander. Moral Essays.

Courthope, in the Elwin and Courthope edition of Pope, thinks the following lines inspired by Mandeville: iii. 13–14 and 25–6.

See below, Elwin and Courthope, under year 1871.

THE PRESENT STATE OF THE REPUBLICK OF LETTERS 1732. [Periodical]

See ix. 32–6 (January) and ix. 93–105 (February) for two reviews of the Origin of Honour; and ix. 142–63 (February) for a review of Berkeley’s answer to Mandeville.

‘We cannot say that every thing in this Piece is new, the Author of a Book intitled: Les pensées sur les Cometes … has very justly shewn us, in that ingenious Performance, how much Men in their manner of living deviate from their Principles …’ (p. 32).

Edition: current; Page: [426]

‘This book … is written in an agreeable, correct, and masterly Stile, as all the other Writings of this Author …’ (p. 93).

SWIFT, Jonathan [?]. A True and Faithful Narrative of what passed in London, during the General Consternation.

See Prose Works, ed. Temple Scott, iv. 283. Cf. above, ii. 24, n.

[1733]BIBLIOTHEQUE BRITANNIQUE, ou Histoire des Ouvrages des Savans de la Grande-Bretagne. 1733. [Periodical]

See i. 1–36 and ii. 1–16 for a careful description of The Origin of Honour. A brief obituary of Mandeville is contained in i. 244–5.

[BRAMSTON, James.] The Man of Taste. Occasion’d by an Epistle of Mr. Pope’s on that Subject. By the Author of the Art of Politics. 1733.

The author writes ironically:

T’improve in Morals Mandevil I read,

And Tyndal’s Scruples are my settled Creed (p. 9).

CAMPBELL, Archibald. An Enquiry into the Original of Moral Virtue wherein it is shewn, (against the Author of the Fable of the Bees, &c.) that Virtue is founded in the Nature of Things, is Unalterable, and Eternal, and the Great Means of Private and Publick Happiness. Edinburgh. 1733.

See above, ii. 25, n. 1. Campbell has substituted his own preface for Innes’s and enlarged the book.

THE COMEDIAN, or Philosophic Enquirer. Numb. IX, and Last. 1733. [Periodical]

See pp. 30–1. ‘… Fable of the Bees … discovers a great Knowledge of human Nature … has several Strokes of true Humour in it …, but the Philosophy, thereof is ill grounded … and the Diction is very inaccurate and vulgar’ (p. 30).

JOURNAL HISTORIQUE DE LA REPUBLIQUE DES LETTRES. Leyden. 1733. [Periodical]

See ii. 422–3 for a letter from London protesting against the leniency towards Mandeville of the Journal Historique (see above under the year 1732). ‘[The Fable] … annéantit toute Différence réelle entre le Vice & la Vertu. …’

JOURNAL LITTERAIRE. The Hague. 1733. [Periodical]

See xx. 207–8 for brief account of Berkeley’s Alciphron and the Letter to Dion.

POPE, Alexander. Essay on Man.

Elwin, in his edition of Pope, thinks the followi:ig lines derived from Mandeville: ii. 129–30, ii. 157–8, ii. 193–4, and iv. 220. Note, also that Pope’s original manuscript had (instead of the present line ii. 240) ‘And public good extracts from private vice’.

See below, under Elwin and Courthope, ii. 445.

[1734]HALLER, Albrecht von. Ueber den Ursprung des Uebels.

Und dieses ist die Welt, worüber Weise klagen,

Die man zum Kerker macht, worin sich Thoren plagen!

Wo mancher Mandewil des guten Merkmal misst,

Die Thaten Bosheit würkt und fühlen leiden ist (i. 71–4).

Edition: current; Page: [427]

JOURNAL LITTERAIRE. The Hague. 1734. [Periodical]

See xxi. 223 for review of Archibald Campbell’s reply to MandevIlle (see above under year 1733) and xxii. 72 for a review of Berkeley’s Alciphron—a review favourable to Berkeley, but not hostile to Mandeville.

LEIPZIGE GELEHRTE ZEITUNGEN. 1734. [Periodical]

See p. 61 for notice of Campbell’s reply to Mandeville. [Cited from Trinius’s Freydenker-Lexicon, p. 347.]

MERCURE DE FRANCE. Paris. 1734. [Periodical]

See p. 1401 for brief notice of the Origin of Honour.

NIEDERSÄCHS. NACHR. VON GELEHRTEN SACHEN. 1734. [Periodical]

See p. 320. [Cited from the Fortsetzung… zu … Jöchers allgemeinem Gelehrten-Lexiko iv. 553.]

A VINDICATION OF THE REVEREND D—— B——Y, from the Scandalous Imputation of being Author of … Alciphron. 1734.

‘Especially seeing he [Berkeley] thought fit to borrow from that Quiver his best Weapons against the Fable of the Bees …; as may be evident to any who will be at the Pains to compare it with the three Papers published among Hibernicus’s Letters, written by … Hutcheson …’ (p. 22).

NOVELLE DELLA REPUBLICA DELLE LETTERE. Venice.[1735] 1735. [Periodical]

See pp. 357–8 for a review of Berkeley’s Alciphron ‘. . . la famosa Favola delle Api …’ (p. 357).

UFFENBACH, ZACHAR. CONRADUS AB. Bibliotheca Uffenbachiana, seu Catalogus Librorum. 4 vol. Frankfort. 1735.

See i. 248 for inclusion of Fable, edition of 1725, under ‘Appendix. Exhibens Libros Vulgo Prohibitos, Sive Suspectæ Fidei et Argumenti Paradoxi atque Profani Scripta.’

BERKELEY, George. A Discourse Addressed to Magistrates and Men in Authority.[1736]

‘We esteem it a horrible thing … with him who wrote the Fable of the Bees, to maintain that “moral virtues are the political offspring which flattery begot upon pride” ’ (Works, ed. Fraser, 1901, iv. 499).

DU CHÂTELET-LOMONT, Gabrielle Émilie. A letter to Algarotti, dated 20 May 1736.

‘Je traduis The fable of the bees de Mandeville; c’est un livre qui mérite que vous le lisiez si vous ne le connaissez pas. Il est amusant et instructif’ (Lettres, ed. Asse, 1882, p. 90).

VOLTAIRE, F. A. de. Le Mondain.

For the indebtedness of this to the Fable, see Morize, L’Apologie du Luxe au XVIIIe Siècle et “Le Mondain” de Voltaire (1909).

[COVENTRY, Henry.] Philemon to Hydaspes; Relating a Second Conversation with Hortensius upon the Subject of False Religion. 1737.[1737]

See pp. 96–7, n.: ‘This false Notion of confounding Superfluities and Vices, is what runs thro’ that whole Piece; otherwise, (as all that Author’s Pieces are) very ingeniously written.’

Edition: current; Page: [428]

Coventry is identified as author by a reference in Bibliotheca Parriana (1827), pp. 85–6, in the Gentleman’s Magazine for 1779, xlix. 413, n., and by Horace Walpole, Letters (ed. Cunningham) i. 7.

GELEHRTE ZEIT. 1737.

[Cited from Lilienthal’s Theologische Bibliothec (1741), p. 326, which refers to p. 697 of the above journal as noticing the Free Thoughts.]

VOLTAIRE, F. A. de. Défense du Mondain ou l’Apologie du Luxe.

According to Morize (L’Apologie du Luxe au XVIIIe Siècle, pp. 162 and 166), lines 11 and 12 are derived from the Fable.

[1738]BIRCH, Thomas. A General Dictionary, Historical and Critical: in which a … Translation of that of … Bayle… is included. 10 vol. 1734–41.

See the article on Mandeville, contributed by Birch. The articles on Mandeville in Chaufepié’s Nouveau Dictionnaire Historique et Critique (1753) and in the Supplement to Biographia Britannica are derived from the General Dictionary.

REPUBL. DER GELEERDEN. 1738. [Periodical]

See article 2 in the issue for September and October for consideration of the Free Thoughts. [Cited from Trinius’s Freydenker-Lexicon, p. 345.]

VOGT, Johann. Catalogus Historico-Criticus Librorum Rariorum. Hamburg. 1738.

See p. 251.

VOLTAIRE, F. A. de Observations sur MM. Jean Lass, Melon et Dutot sur le Commerce, le Luxe, les Monnaies, et les Impots. 1738.

Compare xxii. 363 (Œ uvres Complètes, ed. Moland, 1877–85) with Fable i. 123 and i. 170 for derivation by Voltaire.

WARBURTON, William. The Divine Legation of Moses Demonstrated.

See Works (1811) i. 281–6: ‘… the low buffoonery and impure rhetoric of this wordy declaimer’ (i. 281). Cf. above, i. cxxviii, n. 5. Warburton also has references to Mandeville in his edition of Pope [1751]; see Pope, Works, ed. Elwin and Courthope, ii. 493–4 and iv. 159, n. 4.

[1740]BIBLIOTHEQUE FRANÇOISE, ou Histoire Litteraire de la France. Amsterdam. 1740. [Periodical]

See xxxii. 315–19. ‘Les digressions de Mr. Mandeville sont ennuyeuses, les plaisanteries sont froides, les peintures des mœurs sont sans noblesse & sans finesse. … a … merité le froid accueil qu’on lui a fait en France’ (xxxii. 319).

BIBLIOTHEQUE RAISONNÉE des Ouvrages des Savans de l’Europe. Amsterdam. 1740. [Periodical]

See xxiv. 240 for notice of the French version of the Fable.

FORTGESETZTE SAMMLUNG VON ALTEN UND NEUEN THEOLOGISCHEN SACHEN. Leipsic. 1740. [Periodical]

See pp. 482–3 for notice of Fable. ‘Die höchst ärgerliche Engelländische Schrifft des Mondeville …’ (p. 482).

Edition: current; Page: [429]

GÖTTINGISCHE ZEITUNGEN von gelehrten Sachen auf das Jahr mdccxl. Göttingen. 1740. [Periodical]

See pp. 67–8 for notice of the French version of the Fable, ‘auf Kosten der holländischen Buchhändlergesellschaft … gedrucket’ (p. 67).

MEMOIRES pour l’Histoire des Sciences & des Beaux Arts [Mémoires de Trévoux]. Trévoux. 1740. [Periodical]

See pp. 941–81, 1596–1636, and 2103–47 for serial review of the Fable. ‘… la Traduction est reçue bien plus paisiblement en France …’ [than the original in England] (p. 981).

[STOLLE, Gottlieb.] Kurtze Nachricht von den Büchern und deren Urhebern in der Stollischen Bibliothec. Der neundte Theil. Jena. 1740.

See pp. 52–67 for review of the Free Thoughts in the form of excerpts.

LILIENTHAL, Michael. Theologische Bibliothec, das ist: richtiges Verzeichniss, zulängliche Beschreibung, und bescheidene Beurtheilung der dahin gehörigen vornehmsten Schriften welche in M. Michael Lilienthals … Bücher-Vorrath befindlich sind. Königsberg. 1741.[1741]

See pp. 326–30 for review of Free Thoughts and pp. 330–2 for review of Fable. There is a statement (p. 326) that some people judged the Free Thoughts to be by B. Masle.

CASTEL, Charles Irenéee, Abbé de St. Pierre. Contre l’Opinion de Mandeville. Que Toutes les Passions sont des Vices Injustes & que les Passions, même Injustes sont plus Utiles que Nuizibles à l’Augmantation du Bonheur de la Societié. [In Ouvrajes de Morale et de Politique (Rotterdam, 1741) xvi. 143–56.]

This is a somewhat altered version of the article of similar title in vol. 15 of the same date—pp. 197–212.

[BROWN, John.] Honour a Poem. Inscribed to … Lord Viscount Lonsdale. 1743.[1743]

Th’ envenom’d Stream that flows from Toland’s Quill,

And the rank Dregs of Hobbes and Mandeville.

Detested Names! yet sentenc’d ne’er to die;

Snatch’d from Oblivion’s Grave by Infamy! (ll. 17–69).

NOTIZIE LETTERARIE OLTRAMONTANE [Giornale de’ Letterati]. Rome. 1743.

‘Il fu Dottor Mandeville va più lungi [than Morgan and Chubb]. Arriva insino a combattere questa Religione, che gli altri ne’ loro scritti rispettano’ (ii[2].321–2). Then follows a short and accurate summary of the Fable and the Origin of Honour.

POPE, Alexander. The Dunciad Variorum. With the Prolegomena of Scriblerus.

See ii. 414 (Works, ed. Elwin and Courthope, iv. 159): ‘… Morgan and Mandevil could prate no more… .’ This line first appeared in 1743.

FORTGESETZTE SAMMLUNG VON ALTEN UND NEUEN THEOLOGISCHEN SACHEN. Leipsic. 1745. [Periodical][1745]

See pp. 950–6.

Edition: current; Page: [430]

INDEX EXPURGATORIUS. The French version of the Fable was placed on the Index by decree of 22 May 1745 (Index Librorum Prohibitorum … Pii Sexti, ed. 1806, p. 112).

[1746]DUNKEL, Johann Gottlob Wilhelm. Diatriba Philosophica, qua Sententia, Auctoris Fabulae de Apibus refutatur. Berlin. 1747.

According to the Fortsetzung … zu … Jöchers allgemeinem Gelehrten-Lexiko, iv. 554, Jacob Elsner published an answer to the Fable at Berlin in 1747. This work was, I conjecture, the one referred to by Dunkel, in his Historisch-critische Nachrichten (1753–7) i. 102–3, who states: ‘Im Jahre 1746 habe ich selbst, auf Veranlassung des sel. D. Jacob Elsners in Berlin, eine absonderliche Diatribam philosophicam … ausgearbeitet, und die Handschrift davon um 1747, weil er solche zum Druck zu befördern sich erbot, an ihn nach Berlin übersendet: ob er aber solches Manuscript an einen andern Ort verschickt, oder unter seinen geschriebenen Sachen nach seinem Tode hinterlassen habe, kann ich nicht wissen.’

LEWIS, Edward. Private Vices the Occasion of Publick Calamities. … An Essay. 1747.

Noticed in London Magazine for Nov. 1746. Only the title and a phrase on p. 11 seem to refer to Mandeville.

LUC, Jacques-Fran;ccedil;ois de. Lettre Critique sur la “Fable des Abeilles” de M. Mandeville. Geneva. 1746.

[Cited from Quérard, La France Littéraire (1830) ii. 464.]

[1747][VAUVENARGUES, Luc de Clapiers, Marquis de.] Introduction a la Connoissance de l’Esprit Humain. Paris. 1747.

Several passages may refer to Mandeville—for example this passage from the third book, ‘Du bien et du mal moral’: ‘On demande si la plûpart des vices ne concourent pas au bien public, comme les plus pures vertus. Qui feroit fleurir le commerce sans la vanité, l’avarice, &c.? En un sens cela est très-vrai; mais il faut m’accorder aussi, que le bien produit par le vice est toujours mêlé de grands maux’ (p. 103).

[1748]FEUERLEIN, D. and P. Specimen Concordiae Fidei et Rationis in Vindiciis Religionis Christianae adversus Petrum Baelium, Fingentem, Rempublicam, quae Tota e Veris Christianis est composita, conseruare se non posse. Göttingen. 1748.

[Cited from Dunkel, Historisch-critische Nachrichten (1753–7) i. 102.]

HOLBERG, Ludvig. Epistler. Udgivne … af Chr. Bruun. 5 vol. Copenhagen. 1865–75.

See i. 92–9 (letter 21). ‘Den LACEDÆMONISKE Lovgiver Lycurgus haver ved sin Stiftelse viset, at et Land uden saadanne Laster, om hvis Nødvendighed Mandeville prædiker, ikke alleene kand beskytte sig mod andre, men og blive anseelig’ (i. 95).

[MONTESQUIEU, Baron de la Brède et de.] De l’Esprit des Loix. Geneva. 1748.

See book 7, ch. 1: ‘Plus il y a d’hommes ensemble, plus ils sont vains & sentent naître en eux l’envie de se signaler par de petites choses.’ A footnote to this reads: ‘Dans une grande Ville, dit l’Auteur de la Fable des Abeilles, tome I, p. 133, on s’y habille au dessus de sa qualité, pour être estimé plus qu’on n’est par la multitude. C’est un plaisir pour un esprit foible, presqu’aussi grand que celui de l’accomplissement de ses desirs.’

Edition: current; Page: [431]

[BAUMGARTEN, Siegm. Jac.] Nachrichten von einer Hallischen Bibliothek. Halle. 1748–52.[1749]

See iii. 133, n., for bibliographical notice of the Fable.