VOLUME II: East India Company - Nullification

E

EAST INDIA COMPANY

EAST INDIA COMPANY, a famous association, originally established for prosecuting the trade between England and India, which they acquired a right to carry on exclusively. Since the middle of the last century, however, the company's political became of more importance than their commercial concerns.

—The persevering efforts of the Portuguese to discover a route to India, by sailing round Africa, were crowned with success in 1497. And it may appear singular, that, notwithstanding the exaggerated accounts that had been prevalent in Europe, from the remotest antiquity. with respect to the wealth of India, and the importance to which the commerce with it had raised the Phœnicians and Egyptians in antiquity, the Venetians in the middle ages, and which it was then seen to confer on the Portuguese, the latter should have been allowed to monopolize it for nearly a century after it had been turned into a channel accessible to every nation. But the prejudices by which the people of most European states were actuated in the sixteenth century, and the peculiar circumstances under which they were placed, hindered them from embarking with the alacrity and ardor which might have been expected in this new commercial career. Soon after the Portuguese began to prosecute their discoveries along the coast of Africa, they applied to the pope for a bull, securing to them the exclusive right to and possession of all countries occupied by infidels which the Portuguese either had discovered, or might discover, to the south of Cape Non, on the west coast of Africa, in 27° 54' north latitude; and the pontiff, desirous to display, and at the same time to extend, his power, immediately issued a bull to this effect. Nor, preposterous as a proceeding of this sort would now appear, did any one then doubt that the pope had a right to issue such a bull and that all states and empires were bound to obey it. In consequence, the Portuguese were, for a lengthened period, allowed to prosecute their conquests in India without the interference of any other European power; and it was not till a considerable period after the beginning of the war which the blind and brutal bigotry of Philip II. kindled in the Low Countries, that the Dutch navigators began to display their flag on the eastern ocean, and laid the foundations of their Indian empire.

—The desire to comply with the injunctions in the pope's bull, and to avoid coming into collision, first with the Portuguese, and subsequently with the Spaniards, who had conquered Portugal in 1580, seems to have been the principal cause that led the English to make repeated attempts, in the reigns of Henry VIII. and Edward VI., and the early part of the reign of Elizabeth, to discover a route to India by a northwest or northeast passage—channels from which the Portuguese would have had no pretense for excluding them. But these attempts having proved unsuccessful, and the pope's bull having ceased to be of any effect in England, the English merchants and navigators resolved to be no longer deterred by the imaginary rights of the Portuguese from directly entering upon what was then reckoned by far the most lucrative and advantageous branch of commerce. Captain Stephens, who performed the voyage in 1582, was the first Englishman who sailed to India by the cape of Good Hope. The voyage of the famous Sir Francis Drake contributed greatly to diffuse a spirit of naval enterprise, and to render the English better acquainted with the newly opened route to India. But the voyage of the Edition: current; Page: [2] celebrated Thomas Cavendish was, in the latter respect, the most important. Cavendish sailed from England in a little squadron, fitted out at his own expense, in July, 1586: and having explored the greater part of the Indian ocean, as far as the Philippine islands, and carefully observed the most important and characteristic features of the people and countries which he visited, returned to England, after a prosperous navigation, in September, 1588. But perhaps nothing contributed so much to inspire the English with a desire to embark in the Indian trade as the captures that were made about this period from the Spaniards. A Portuguese East India ship, or carrack, captured by Sir Francis Drake during his expedition to the coast of Spain, inflamed the capidity of the merchants by the richness of her cargo, at the same time that the papers found on board gave specific information respecting the traffic in which she had been engaged. A still more important capture of the same sort was made in 1593. An armament, fitted out for the East Indies by Sir Walter Raleigh, and commanded by Sir John Borroughs, fell in, near the Azores, with the largest of all the Portuguese carracks, a ship of 1,600 tons burden, carrying 700 men and 36 brass cannon; and, after an obstinate conflict, carried her into Dartmouth. She was the largest vessel that had been seen in England; and her cargo, consisting of gold, spices, calicoes, silks, pearls, drugs, porcelain, ivory, etc., excited the ardor of the English to engage in so opulent a commerce.

—In consequence of these and other concurring causes, an association was formed in London in 1599 for prosecuting the trade to India. The adventurers applied to the queen for a charter of incorporation, and also for power to exclude all other English subjects, who had not obtained a license from them, from carrying on any species of traffic beyond the cape of Good Hope or the straits of Magellan. As exclusive companies were then very generally looked upon as the best instruments for prosecuting most branches of commerce and industry, the adventurers seem to have had little difficulty in obtaining their charter, which was dated Dec. 31, 1600. The corporation was entitled: "The Governor and Company of Merchants of London trading into the East Indies." The first governor (Thomas Smythe, Esq.) and twenty-four directors were nominated in the charter, but power was given to the company to elect a deputy governor, and in future to elect their governor and directors, and such other office bearers as they might think fit to appoint. They were empowered to make by laws; to inflict punishments, either corporal or pecuniary, provided such punishments were in accordance with the laws of England; to export all sorts of goods free of duty for four years; and to export foreign coin or bullion to the amount of £30,000 a year, £6,000 of the same being previously coined at the mint; but they were obliged to import, within six months after the completion of every voyage except the first, the same quantity of silver, gold and foreign coin that they had exported. The duration of the charter was limited to a period of fifteen years; but with and under the condition that, if it were not found for the public advantage, it might be canceled at any time upon two years' notice being given. Such was the origin of the British East India company, the most celebrated commercial association of ancient or modern times, and which in course of time extended its sway over the whole of the Mogul empire.

—It might have been expected that, after the charter was obtained, considerable eagerness would have been manifested to engage in the trade. But such was not the case. Notwithstanding the earnest calls and threats of the directors, many of the adventurers could not be induced to come forward to pay their proportion of the charges incident to the fitting out of the first expedition. And as the directors seem either to have wanted power to enforce their resolutions, or thought it better not to exercise it, they formed a subordinate association, consisting of such members of the company as were really willing to defray the cost of the voyage, and to bear all the risks and losses attending it, on condition of their having the exclusive right to whatever profits might arise from it. It was by such subordinate associations that the trade was conducted during the first thirteen years of the company's existence.

—The first expedition to India, the cost of which amounted, ships and cargoes included, to £69.091, consisted of five ships, the largest being 600, and the smaller 130 tons burden. The goods put on board were principally bullion, iron, tin, broadcloths, cutlery, glass, etc. The chief command was intrusted to Capt. James Lancaster, who had already been in India. They set sail from Torbay on Feb. 13, 1601. Being very imperfectly acquainted with the seas and countries they were to visit, they did not arrive at their destination, Acheen in Sumatra, till June 5, 1602. But though tedious, the voyage was, on the whole, uncommonly prosperous. Lancaster entered into commercial treaties with the kings of Acheen and Bantam; and having taken on board a valuable cargo of pepper and other produce, he was fortunate enough, on his way home, to fall in with and capture, in concert with a Dutch vessel, a Portuguese carrack of 900 tons burden, richly laden. Lancaster returned to the Downs on Sept. 11, 1603. (Modern Universal History, vol. x. p. 16; Macpherson's Commerce of the European Powers with India, p. 81.)

—But notwithstanding the favorable result of this voyage, the expeditions fitted out in the years immediately following, though sometimes consisting of larger ships, were not, at an average, materially increased. In 1612 Capt. Best obtained from the court at Delhi several considerable privileges; and among others, that of establishing a factory at Surat, which city was henceforth looked upon as the principal British station in the west of India, till the acquisition of Bombay.

—In establishing factories in India, the English only followed the Edition: current; Page: [3] example of the Portuguese and Dutch. It was contended that they were necessary to serve as dépôts for the goods collected in the country for exportation to Europe, as well as for those imported into India, in the event of their not meeting with a ready market on the arrival of the ships. Such establishments, it was admitted, are not required in civilized countries; but the peculiar and unsettled state of India was said to render them indispensable there. Whatever weight may be attached to this statement, it is obvious that factories formed for such purposes could hardly fail of speedily degenerating into a species of forts. The security of the valuable property deposited in them furnished a specious pretext for putting them in a condition to withstand an attack; while the agents, clerks, warehousemen, etc., formed a sort of garrison. Possessing such strongholds, the Europeans were early emboldened to act in a manner quite inconsistent with their character as merchants, and but a very short time elapsed before they began to form schemes for monopolizing the commerce of particular districts, and acquiring territorial dominion.

—Though the company met with several heavy losses during the earlier part of their traffic with India, from shipwrecks and other unforeseen accidents, and still more from the hostility of the Dutch, yet, on the whole, the trade was decidedly profitable. There can, however, be little doubt that their gains at this early period have been very much exaggerated. During the first thirteen years they are said to have amounted to 132 per cent. But then it should be borne in mind, as Mr. Grant has justly stated, that the voyages were seldom accomplished in less than thirty months, and sometimes extended to three or four years; and it should further be remarked, that, on the arrival of the ships at home, the cargoes were disposed of at long credits of eighteen months or two years; and that it was frequently even six or seven years before the concerns of a single voyage were finally adjusted. (Sketch of the History of the Company, p. 13.) When these circumstances are taken into view, it will immediately be seen that the company's profits were not, really, by any means so great as has been represented. Still it may not be uninstructive to remark that the principal complaint that was then made against the company did not proceed so much on the circumstance of its charter excluding the public from any share in an advantageous traffic, as in its authorizing the company to export gold and silver of the value of £30,000 a year. It is true that the charter stipulated that the company should import an equal quantity of gold and silver within six months of the termination of every voyage; but the enemies of the company contended that this condition was not complied with, and that it was, besides, highly injurious to the public interest, and contrary to all principle, to allow gold and silver to be sent out of the kingdom. The merchants and others interested in the support of the company could not controvert the reasoning of their opponents without openly impugning the ancient policy of absolutely preventing the exportation of the precious metals. They did not, however, venture to contend, if the idea really occurred to them, that the exportation of bullion to the east was advantageous on the broad ground of the commodities purchased by it being of greater value in England; but they contended that the exportation of bullion to India was advantageous because the commodities thence imported were chiefly re-exported to other countries from which a much greater quantity of bullion was obtained than had been required to pay for them in India. Mr. Thomas Mun, a director of the East India company, and the ablest of its early advocates, ingeniously compares the operations of the merchant in conducting a trade carried on by the exportation of gold and silver, to the seed-time and harvest of agriculture. "If we only behold," says he, "the actions of the husbandman in the seed-time, when he casteth away much good corn into the ground, we shall account him rather a madman than a husbandman; but when we consider his labors in the harvest, which is the end of his endeavors, we find the worth and plentiful increase of his actions" (Treasure by Foreign Trade, p 50, ed. 1664)

—We may here remark that what has been called the mercantile system of political economy, or that system which measures the progress of a country in the career of wealth by the supposed balance of payments in its favor, or by the estimated excess of the value of its exports over that of its imports, appears to have originated in the excuses now set up for the exportation of bullion. Before this epoch the policy of prohibiting the exportation of bullion had been universally admitted; but it now began to be pretty generally allowed that its exportation might be productive of advantage, provided it occasioned the subsequent exportation of a greater amount of raw or manufactured products to countries whence bullion was obtained for them. This, when compared with the previously existing prejudice (for it hardly deserves the name of system) which wholly interdicted the exportation of gold and silver, must be allowed to be a considerable step in the progress to sounder opinions. The maxim ce n'est que le premier pas qui coute was strikingly verified on this occasion. The advocates of the East India company began gradually to assume a higher tone, and at length boldly contended that bullion was nothing but a commodity, and that its exportation should be rendered as free as that of anything else. Nor were these opinions confined to the partners of the East India company, they were gradually communicated to others; and many eminent merchants were taught to look with suspicion on several of the previously received dogmas with respect to commerce, and were, in consequence, led to acquire more correct and comprehensive views. The new ideas ultimately made their way into the house of commons; Edition: current; Page: [4] and in 1663 the statutes prohibiting the exportation of foreign coin and bullion were repealed, and full liberty given to the East India company and to private traders to export them in unlimited quantities.

—But the objection to the East India company, or rather the East India trade, on the ground of its causing the exportation of gold and silver, admitted of a more direct and conclusive, if not a more ingenious reply How compendious soever the ancient intercourse with India by the Red sea and the Mediterranean, it was unavoidably attended with a good deal of expense. The productions of the remote parts of Asia, brought to Ceylon, or the ports on the Malabar coast, by the natives, were there put on board the ships which arrived from the Arabian gulf. At Berenice they were landed, and carried by camels 250 miles to the banks of the Nile. They were there again embarked, and conveyed down the river to Alexandria, whence they were dispatched to different markets. The addition to the price of goods by such a multiplicity of operations must have been considerable. Pliny says that the cost of the Arabian and Indian products brought to Rome (A. D. 70) was increased a hundredfold by the expenses of transit (Hist. Nat, lib. vi., c. 23). but there can be little or no doubt that this is to be regarded as a rhetorical exaggeration. There are good grounds for thinking that the less bulky sorts of eastern products, such as silk, spices, balsams, precious stones, etc., which were those principally made use of at Rome, might, supposing there were no political obstacles in the way, be conveyed from most parts of India to the ports on the Mediterranean by way of Egypt, at a decidedly cheaper rate than they could be conveyed to them by the cape of Good Hope.

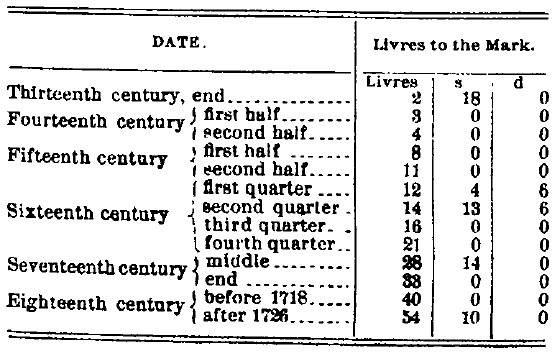

—But at the period when the latter route to India began to be frequented, Syria, Egypt, etc., were occupied by Turks and Mamelukes—barbarians who despised commerce and navigation, and were, at the same time, extremely jealous of strangers, especially of Christians or infidels. The price of the commodities obtained through the intervention of such persons was necessarily very much enhanced; and the discovery of the route by the cape of Good Hope was, consequently, of the utmost importance; for, by putting an end to the monopoly enjoyed by the Turks and Mamelukes, it introduced, for the first time, something like competition into the Indian trade, and enabled the western parts of Europe to obtain supplies of Indian products for about one-third of what they had previously cost. Mr. Mun, in a tract published in 1621, estimates the quantity of Indian commodities imported into Europe, and their cost when bought in Aleppo and India, as follows:

| lbs. | £ | s. | d. |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6,000,000 pepper cost, with charges, etc, at Aleppo, 2s. per lb... | 600,000 | 0 | 0 |

| 450,000 cloves, at 4s. 9d... | 106,875 | 10 | 0 |

| 150,000 mace, at 4s. 9d... | 35,626 | 0 | 0 |

| 400,000 nutmegs, at 2s. 4d... | 46,666 | 2 | 4 |

| 350,000 indigo, at 4s. 4d... | 75,833 | 6 | 8 |

| 1,000,000 Persian raw silk, at 12s... | 600,000 | 0 | 0 |

| 1,465,000 | 19 | 0 |

But the same quantities of the same commodities cost, when bought in the East Indies, according to Mr. Mun, as follows:

| lbs | £ | s. | d. |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6,000,000 pepper, at 2½d. per lb... | 62,500 | 0 | 0 |

| 450,000 cloves, at 9d... | 15,875 | 0 | 0 |

| 150,000 mace, at 8d... | 5,000 | 0 | 0 |

| 400,000 nutmegs, at 4d... | 6,666 | 13 | 4 |

| 350,000 indigo, at ls. 2d... | 20,416 | 12 | 4 |

| 1,000,000 raw silk, at 8s... | 400,000 | 0 | 0 |

| 511,458 | 5 | 8 |

Which being deducted from the former, leaves a balance of £953,542 13s. 4d. And supposing that the statements made by Mr. Mun are correct, and that allowance is made for the difference between the freight from Aleppo and India, the result would indicate the saving which the discovery of the route by the cape of Good Hope occasioned in the purchase of the above-mentioned articles. (A Discourse of Trade from England to the East Indies, by T. M., original edition, p. 10. This tract which is very scarce, is reprinted in Purchas' Pilgrims.)

—In the same publication (p. 37) Mr. Mun informs us that, from the beginning of the company's trade to July, 1620, they had sent seventy-nine ships to India; of which thirty-four had come home safely and richly laden, four had been worn out by long service in India, two had been lost in careening, six had been lost by the perils of the sea, and twelve had been captured by the Dutch. Mr. Mun further states that the exports to India since the formation of the company had amounted to £840,376; that the produce brought from India had cost £356,288, and had produced in England the enormous sum of £1,914,600; that the quarrels with the Dutch had occasioned a loss of £84,088; and that the stock of the company, in ships, goods in India, etc., amounted to £400,000.

—The hostility of the Dutch to which Mr. Mun has here alluded, was long a very formidable obstacle to the company's success. The Dutch early endeavored to obtain the exclusive possession of the spice trade, and were not at all scrupulous as to the means by which they attempted to effect this their favorite object. The English, on their part, naturally exerted themselves to obtain a share of so valuable a commerce; and as neither party was disposed to abandon its views and pretensions, the most violent animosities grew up between them. In this state of things it would be ridiculous to suppose that unjustifiable acts were not committed by the one party as well as the other; though the worst act of the English appears venial when compared with the conduct of the Dutch in the massacre at Amboyna in 1622. While, however, the Dutch company was vigorously supported by the government at home, the English company met with no efficient assistance from the feeble and vacillating policy of James and Charles. The Dutch either despised their remonstrances, or defeated them by an apparent compliance; so that no real reparation was obtained for the outrages they had committed. During the civil war Indian affairs were necessarily Edition: current; Page: [5] lost sight of; and the Dutch continued, until the ascendency of the republican party had been established, to reign triumphant in the east, where the English commerce was nearly annihilated.

—But, notwithstanding their depressed condition, the company's servants in India laid the foundation, during the period in question, of the settlements at Madras and in Bengal. Permission to build Fort St. George was obtained from the native authorities in 1640. In 1658 Madras was raised to the station of presidency. In 1645 the company began to establish factories in Bengal, the principal of which was at Hooghly. These were, for a lengthened period, subordinate to the presidency at Madras.

—No sooner, however, had the civil war terminated than the arms and councils of Cromwell retrieved the situation of English affairs in India. The war which broke out between the long parliament and the Dutch in 1652 was eminently injurious to the latter. In the treaty of peace, concluded in 1654, it was stipulated that indemnification should be made by the Dutch for the losses and injuries sustained by the English merchants and factories in India. The 27th article bears, "that the lords, the states-general of the United Provinces, shall take care that justice be done upon those who were partakers or accomplices in the massacre of the English at Amboyna, as the republic of England is pleased to term that fact, provided any of them be living." A commission was at the same time appointed, conformably to another article of the treaty, to inquire into the reciprocal claims which the subjects of the contracting parties had upon each other for losses sustained in India, Brazil, etc.; and, upon their decision, the Dutch paid the sum of £85,000 to the East India company, and £3,615 to the heirs or executors of the sufferers at Amboyna. (Bruce's Annals, vol. i., p. 489)

—The charter under which the East India company prosecuted their exclusive trade to India, being merely a grant from the crown, and not ratified by any act of parliament, was understood by the merchants to be at an end when Charles I. was deposed. They were confirmed in this view of the matter from the circumstance of Charles having himself granted, in 1635, a charter to Sir William Courten and others, authorizing them to trade with those parts of India with which the company had not established any regular intercourse. The reasons alleged in justification of this measure, by the crown, were, that "the East India company had neglected to establish fortified factories, or seats of trade, to which the king's subjects could resort with safety; that they had consulted their own interests only, without any regard to the king's revenue; and in general that they had broken the condition on which their charter and exclusive privileges had been granted to them." (Rym. Fœdera, vol. xx, p. 146.)

—Courten's association, for the foundation of which such satisfactory reasons had been assigned, continued to trade with India during the remainder of Charles' reign; and no sooner had the arms of the commonwealth forced the Dutch to desist from their depredations, and to make reparation for the injuries they had inflicted on the English in India, than private adventurers engaged in great numbers in the Indian trade, and carried it on with a zeal, economy and success that monopoly can never expect to rival. It is stated in a little work, entitled Britannia Languens, published in 1680, the author of which has evidently been a well-informed and intelligent person, that during the years 1653, 1654, 1655, and 1656, when the trade to India was open, the private traders imported East India commodities in such large quantities, and sold them at such reduced prices, that they not only fully supplied the British markets, but had even come into successful competition with the Dutch in the market of Amsterdam, "and very much sunk the actions (shares) of the Dutch East India company." (P. 132.) This circumstance naturally excited the greatest apprehensions on the part of the Dutch company; for, besides the danger that they now ran of being deprived, by the active competition of the English merchants, of a considerable part of the trade which they had previously enjoyed, they could hardly expect that, if the trade were thrown open in England, the monopoly would be allowed to continue in Holland. A striking proof of what is now stated is to be found in a letter in the third volume of Thurlow's State Papers, dated at the Hague, Jan. 15, 1654, where it is said that "the merchants of Amsterdam have advice that the lord protector intends to dissolve, the East India company at London, and to declare the navigation and commerce of the East Indies free and open; which doth cause great jealousy at Amsterdam, as a thing that will very much prejudice the East India company in Holland."

—Feeling that it was impossible to contend with the private adventurers under a system of fair competition, the moment the treaty with the Dutch had been concluded the company began to solicit a renewal of their charter; but in this they were not only opposed by the free traders, but by a part of themselves. To understand how this happened, it may be proper to mention that Courten's association, the origin of which has been already noticed, had begun, in 1648, to found a colony in Assuda, an island near Madagascar. The company, alarmed at this project, applied to the council of state to prevent its being carried into effect: and the council, without entering on the question of either party's rights, recommended them to form a union, which was accordingly effected in 1649. But the union was, for a considerable time, rather nominal than real; and when the Dutch war had been put an end to, most of those holders of the company's stock who had belonged to Courten's association joined in petitioning the council of state that the trade might in future be carried on, not by a joint stock, but by a regulated company; so that each individual engaging in it might be allowed to employ his own stock, servants and shipping in whatever way he might conceive Edition: current; Page: [6] most for his own advantage. (Petition of Adventurers, Nov. 17, 1656; Bruce's Annals, vol. i., p. 518.)

—This proposal was obviously most reasonable. The company had always founded their claim to a monopoly of the trade on the alleged ground of its being necessary to maintain forts, factories and ships of war in India; and that as this was not done by government, it could only be done by a company. But, by forming the traders with India into a regulated company, they might have been subjected to whatever rules were considered most advisable; and such special duties might have been laid on the commodities they exported and imported as would have sufficed to defray the public expenses required for carrying on the trade, at the same time that the inestimable advantages of free competition would have been secured; each individual trader being left at liberty to conduct his enterprises, subject only to a few general regulations, in his own way and for his own advantage.

—But notwithstanding the efforts of the petitioners, and the success that was clearly proved to have attended the operations of the private traders, the company succeeded in obtaining a renewal of their charter from Cromwell in 1657. Charles II. confirmed this charter in 1661, and at the same time conferred on them the power of making peace or war with any power or people not of the Christian religion; of establishing fortifications, garrisons and colonies; of exporting ammunition and stores to their settlements duty free; of seizing and sending to England such British subjects as should be found trading to India without their leave; and of exercising civil and criminal jurisdiction in their settlements, according to the laws of England. Still, however, as this charter was not fully confirmed by any act of parliament, it did not prevent traders, or interlopers as they were termed, from appearing within the limits of the company's territories. The energy of private commerce, which, to use the words of Mr. Orme, "sees its drift with eagles' eyes," formed associations at the risk of trying the consequence at law, being safe at the outset and during the voyage, since the company were not authorized to stop or seize the ships of those who thus attempted to come into competition with them. Hence their monopoly was by no means complete; and it was not till after the revolution, and when a free system of government had been established at home, that by a singular contradiction, the authority of parliament was interposed to enable the company wholly to engross the trade with the east.

—In addition to the losses arising from this source, the company's trade suffered severely, during the reign of Charles II. from the hostilities that were then waged with the Dutch, and from the confusion and disorders caused by contests among the native princes; but in 1668 the company obtained a very valuable acquisition in the island of Bombay. Charles II. acquired this island as a part of the marriage portion of his wife, Catherine of Portugal; and it was now made over to the company, on condition of their not selling or alienating it to any persons whatever, except such as were subjects of the British crown. They were allowed to legislate for their new possession; but it was enjoined that their laws should be consonant to reason, and "as near as might be" agreeable to the practice of England. They were authorized to maintain their dominion by force of arms; and the natives of Bombay were declared to have the same liberties as natural born subjects. The company's western presidency was soon after transferred from Surat to Bombay.

—In 1664 the French East India company was formed, and ten years afterward they laid the foundation of their settlementsat Pondicherry.

—But the reign of Charles II. is chiefly memorable in the company's annals from its being the era of the commencement of the tea trade. The first notice of tea in the company's records is found in a dispatch addressed to their agent at Bantam, dated Jan. 24, 1667-8, in which he is desired to send home 100 lbs. of tea, "the best he can get" (Bruce's Annals, vol. ii., p. 210.) Such was the late and feeble beginning of the tea trade—a branch of commerce that has long been of vast importance to the British nation, and without which it is more than probable that the East India company would long since have ceased to exist, at least as a mercantile body.

—In 1677 the company obtained a fresh renewal of their charter; receiving at the same time an indemnity for all past misuse of their privileges, and authority to establish a mint at Bombay.

—During the greater part of the reigns of Charles II. and James II. the company's affairs at home were principally managed by the celebrated Sir Josiah Child, the ablest commercial writer of the time; and in India by his brother, Sir John Child. In 1681 Sir Josiah published an apology for the company, under the signature of —"A Treatise wherein is demonstrated that the East India Trade is the most National of all Foreign Trades;" in which, besides endeavoring to vindicate the company from the objections that had been made against it, he gives an account of its state at the time. From this account it appears that the company consisted of 556 partners; that they had from 35 to 36 ships of from 100 to 775 tons, employed in the trade between England and India, and from port to port in India (p. 23); that the customs duties upon the trade amounted to about £60,000 a year; and that the value of the exports, "in lead, tin, cloth, and stuffs, and other commodities of the production and manufacture of England," amounted to about £60,000 or £70,000 a year. Sir Josiah seems to have been struck, as he well might, by the inconsiderable amount of the trade; and he therefore dwells on the advantages of which it was indirectly productive in enabling the English to obtain supplies of raw silk, pepper, etc., at a much lower price than they would otherwise have fetched. But this, though true, proved nothing in favor of the company; it being an admitted fact that those articles were furnished at a still lower price by the Edition: current; Page: [7] interlopers or private traders.

—Sir Josiah Child was one of the first who projected the formation of a territorial empire in India. But the expedition fitted out in 1686, in the view of accomplishing this purpose, proved unsuccessful; and the company were glad to accept peace on the terms offered by the Mogul. Sir John Child, having died during the course of these transactions, was succeeded in the principal management of the company's affairs in India by Mr. Vaux. On the appointment of the latter, Sir Josiah Child, to whom he owed his advancement, exhorted him to act with vigor, and to carry whatever instructions he might receive from home into immediate effect. Mr. Vaux returned for answer, that he should endeavor to acquit himself with integrity and justice, and that he would make the laws of his country the rule of his conduct. Sir Josiah Child's answer to this letter is curious. "He told Mr. Vaux roundly that he expected his orders were to be his rules, and not the laws of England, which were a heap of nonsense, compiled by a few ignorant country gentlemen, who hardly knew how to make laws for the good government of their own private families, much less for the regulating of companies and foreign commerce." (Hamilton's New Account of the East Indies, vol. i., p. 232)

—During the latter part of the reign of Charles II. and that of his successor, the number of private adventurers, or interlopers, in the Indian trade, increased in an unusual degree. The company vigorously exerted themselves in defense of what they conceived to be their rights; and the question with respect to the validity of the powers conferred on them by their charter was at length brought to issue by a prosecution carried on at their instance against Mr. Thomas Sandys, for trading to the East Indies without their license. Judgment was given in favor of the company in 1685. But this decision was ascribed to corrupt influence; and instead of allaying only served to increase the clamor against them. The meeting of the convention parliament gave the company's opponents hopes of a successful issue to their efforts; and had they been united, they might probably have succeeded. Their opinions were, however, divided—part being for throwing the trade open, and part for the formation of a new company on a more liberal footing. The latter being formed into a body, and acting in unison, the struggle against the company was chiefly carried on by them. The proceedings that took place on this occasion are among the most disgraceful in the history of England. The most open and unblushing corruption was practiced by all parties. "It was, in fact, a trial which side should bribe the highest; public authority inclining to one or other as the irresistible force of gold directed." (Modern Universal History, vol. x., p. 127.) Government appears, on the whole, to have been favorable to the company, and they obtained a fresh charter from the crown in 1693. But in the following year the trade was virtually laid open by a vote of the house of commons, "that all the subjects of England had an equal right to trade to the East Indies unless prohibited by act of parliament." Matters continued on this footing till 1698. The pecuniary difficulties in which government was then involved induced them to apply to the company for a loan of £2,000,000, for which they offered 8 per cent. interest. The company offered to advance £700,000, at 4 per cent.; but the credit of government was at the time so low, that they preferred accepting an offer from the associated merchants, who had previously opposed the company, of the £2,000,000, at 8 per cent., on condition of their being formed into a new and exclusive company. While this project was in agitation, the advocates of free trade were not idle, but exerted themselves to show that, instead of establishing a new company, the old one ought to be abolished. But however conclusive, their arguments, having no adventitious recommendations in their favor, failed of making any impression. The new company was established by authority of the legislature; and as the charter of the old company was not yet expired, the novel spectacle was exhibited of two legally constituted bodies, each claiming an exclusive right to the trade of the same possessions!

—Notwithstanding all the pretensions set up by those who had obtained the new charter during their struggle with the old company, it was immediately seen that they were as anxious as the latter to suppress everything like free trade. They had not, it was obvious, been actuated by any enlarged views, but merely by a wish to grasp at the monopoly, which they believed would redound to their own individual interest. The public, in consequence, became equally disgusted with both parties; or if there were any difference, it is probable that the new company was looked upon with the greatest aversion, inasmuch as we are naturally more exasperated by what we conceive to be duplicity and bad faith than by fair, undisguised hostility.

—At first the mutual hatred of the rival associations knew no bounds. But they were not long in perceiving that such conduct would infallibly end in their ruin; and that while one was laboring to destroy the other, the friends of free trade might step in and procure the dissolution of both. In consequence they became gradually reconciled; and in 1702, having adjusted their differences, they resolved to form themselves into one company, entitled The United Company of Merchants of England trading to the East Indies.

—The authority of parliament was soon after interposed to give effect to this agreement.

—The united company engaged to advance £1,200,000 to government without interest, which, as a previous advance had been made of £2,000,000 at 8 per cent., made the total sum due to them by the public £3,200,000, bearing interest at 5 per cent., and government agreed to ratify the terms of their agreement, and to extend the charter to March 25, 1726, with three years' notice.

— Edition: current; Page: [8] While these important matters were transacting at home, the company had acquired some additional possessions in India. In 1692 the Bengal agency was transferred from Hooghly to Calcutta. In 1698 the company acquired a grant, from one of the grandsons of Aurengzebe, of Calcutta and two adjoining villages: with leave to exercise judiciary powers over the inhabitants, and to erect fortifications. These were soon after constructed, and received, in compliment to William III., then king of England, the name of Fort William. The agency at Bengal, which had hitherto been subsidiary only, was now raised to the rank of a presidency.

—The vigorous competition that had been carried on, for some years before the coalition of the old and new companies, between them and the private traders, had occasioned a great additional importation of Indian silks, piece goods and other products, and a great reduction of their price. These circumstances occasioned the most vehement complaints among the home manufacturers, who resorted to the arguments invariably made use of on such occasions by those who wish to exclude foreign competition; affirming that manufactured Indian goods had been largely substituted for those of England; that the English manufacturers had been reduced to the cruel necessity either of selling nothing, or of selling their commodities at such a price as left them no profit; that great numbers of their workmen had been thrown out of employment; and, last of all, that Indian goods were not bought by British goods, but by gold and silver, the exportation of which had caused the general impoverishment of the kingdom! The merchants and others interested in the Indian trade could not, as had previously happened to them in the controversy with respect to the exportation of bullion, meet these statements without attacking the principles on which they rested, and maintaining, in opposition to them, that it was for the advantage of every people to buy the products they wanted in the cheapest market. This just and sound principle was, in consequence, enforced in several petitions presented to parliament by the importers of Indian goods; and it was also enforced in several able publications that appeared at the time. But these arguments, how unanswerable soever they may now appear, had then but little influence, and in 1701 an act was passed, prohibiting the importation of Indian manufactured goods for home consumption.

—For some years after the re-establishment of the company, it continued to prosecute its efforts to consolidate and extend its commerce. But the unsettled state of the Mogul empire, coupled with the determination of the company to establish factories in every convenient situation, exposed their affairs to perpetual vicissitudes. In 1715 it was resolved to send an embassy to Delhi, to solicit from Furucksur, an unworthy descendant of Aurengzebe, an extension and confirmation of the company's territory and privileges. Address, accident, and the proper application of presents conspired to insure the success of the embassy. The grants or patents solicited by the company were issued in 1717—thirty-four in all. The substance of the privileges they conferred was, that English vessels wrecked on the coast of the empire should be exempt from plunder; that the annual payment of a stipulated sum to the government of Surat should free the English trade at that port from all duties and exactions, that those villages contiguous to Madras, formerly granted and afterward refused by the government of Arcot, should be restored to the company; that the island of Dieu, near the port of Masulipatam, should belong to the company, paying for it a fixed rent; that in Bengal, all persons, whether European or native, indebted or accountable to the company, should be delivered up to the presidency on demand; that goods of export or import, belonging to the English, might, under a dustuck or passport from the president of Calcutta, be conveyed duty free through the Bengal provinces: and that the English should be at liberty to purchase the lordship of thirty-seven towns contiguous to Calcutta, and in fact commanding both banks of the river for ten miles south of that city. (Grant's Sketch of the History of the East India Company, p. 128.)

—The important privileges thus granted were long regarded as constituting the great charter of the English in India. Some of them, however, were not fully conceded, but were withheld, or modified by the influence of the emperor's lieutenants, or soubahdars.

—In 1717 the company found themselves in danger from a new competitor. In the course of that year some ships appeared in India, fitted out by private adventurers from Ostend. Their success encouraged others to engage in the same line, and in 1722 the adventurers were formed into a company under a charter from his imperial majesty. The Dutch and English companies, who had so long been hostile to each other, at once laid aside their animosities, and joined heartily in an attempt to crush their new competitors. Remonstrances being found ineffectual, force was resorted to; and the vessels of the Ostend company were captured under the most frivolous pretenses, in the open seas and on the coasts of Brazil. The British and Dutch governments abetted the selfish spirit of hostility displayed by their respective companies; and the emperor was, in the end, glad to purchase the support of Great Britain and Holland to the pragmatic sanction, by the sacrifice of the company at Ostend.

—Though the company's trade had increased, it was still inconsiderable; and it is very difficult, indeed, when one examines the accounts that have from time to time been published of the company's mercantile affairs, to imagine how the idea ever came to be entertained that their commerce was of any considerable, much less paramount, importance. At an average of the ten years ending with 1724, the total value of the British manufactures and other products annually exported to India amounted Edition: current; Page: [9] to only £92,410 12s. 6d. The average value of the bullion annually exported during the same period amounted to £518,102 11s.; making the total annual average exports £617,513 3s. 10d.—a truly pitiful sum, when we consider the wealth, population and industry of the countries between which the company's commerce was carried on, and affording by its smallness a strong presumptive proof of the effect of the monopoly in preventing the growth of the trade.

—In 1730, though there were three years still unexpired of the company's charter, a vigorous effort was made by the merchants of London, Bristol and Liverpool to prevent its removal. It has been said that the gains of the company, had they been exactly known, would not have excited any very envious feelings on the part of the merchants; but, being concealed, they were exaggerated; and the boasts of the company as to the importance of their trade contributed to spread the belief that their profits were enormous, and consequently stimulated the exertions of their opponents. Supposing, however, that the real state of the case had been known, there was still enough to justify the almost exertions on the part of the merchants; for the limited profits made by the company, notwithstanding their monopoly, were entirely owing to the misconduct of their agents, which they had vainly endeavored to restrain, and to the waste inseparable from such unwieldy establishments.

—The merchants on this occasion followed the example that had been set by the petitioners for free trade in 1656. They offered, in the first place, to advance the £3,200,000 lent by the company to the public, on more favorable terms; and, in the second place, they proposed that the subscribers to this loan should be formed into a regulated company, for opening the trade, under the most favorable circumstances, to all classes of their countrymen.

—It was not intended that the company should trade upon a joint stock, and in their corporate capacity, but that every individual who pleased should trade in the way of private adventure. The company were to have the charge of executing and maintaining the forts and establishments abroad; and for this, and for other expenses attending what was called the enlargement and preservation of the trade, it was proposed that they should receive a duty of 1 per cent. upon all exports to India, and of 5 per cent. upon all imports from it. For ensuring obedience to this and other regulations, it was to be enacted that no one should engage in trade to India without license from the company; and it was proposed that thirty-one years, with three years' notice, should be granted as the duration of their peculiar privilege.

—"It appears from this," says Mr. Mill, "that the end which was proposed to be answered by incorporating such a company was the preservation and erection of the forts, buildings and other fixed establishments required for the trade of India. This company promised to supply that demand which has always been held forth as peculiar to the Indian trade, as the grand exigency which, distinguishing the traffic with India from all other branches of trade, rendered monopoly advantageous in that peculiar case, how much soever it might be injurious in others. While it provided for this real or pretended want, it left the trade open to all the advantages of private enterprise, private vigilance, private skill and private economy—the virtues by which individuals thrive and nations prosper; and it gave the proposed company an interest in the careful discharge of its duty by making its profits increase in exact proportion with the increase of the trade, and, of course, with the facilities and accommodation by which the trade was promoted.

—Three petitions were presented to the house of commons in behalf of the proposed company, by the merchants of London, Bristol and Liverpool. It was urged that the proposed company would, through the competition of which it would be productive, cause a great extension of the trade; that it would produce a larger exportation of English produce and manufactures in India, and reduce the price of all Indian commodities to the people at home; that new channels of traffic would be opened in Asia and America as well as in Europe; that the duties of customs and excise would be increased; and that the waste and extravagance caused by the monopoly would be entirely avoided." (Mill's India, vol. iii., p. 37.)

—But these arguments did not prevail. The company magnified the importance of their trade, and contended that it would be unwise to risk advantages already realized for the sake of those that were prospective and contingent. They alleged that, if the trade to India were thrown open, the price of goods in India would be so much enhanced by the competition of different traders, and their price in England so much diminished, that the freedom of the trade would certainly end in the ruin of all who had been foolish enough to adventure in it. To enlarge on the fallacy of these statements would be worse than superfluous. It is obvious that nothing whatever could have been risked, and that a great deal would have been gained, by opening the trade in the way that was proposed. And if it were really true that the trade to India ought to be subjected to a monopoly, lest the traders by their competition should ruin each other, it would follow that the trade to America—and not that only, but every branch both of the foreign and home trade of the empire—should be surrendered to exclusive companies. But such as the company's arguments were, they seemed satisfactory to parliament. They, however, consented to reduce the interest on the debt due to them by the public from 5 to 4 per cent., and contributed a sum of £200,000 for the public service. On these conditions it was agreed to extend their exclusive privileges to Lady-day, 1766, with the customary addition of three years' notice.

—For about fifteen years from this period the company's affairs went on without any very prominent changes. But notwithstanding the Edition: current; Page: [10] increased importation of tea, the consumption of which now began rapidly to extend, their trade continued to be comparatively insignificant. At an average of the eight years ending with 1741, the value of the British goods and products of all sorts, exported by the company to India and China, amounted to only £157,944 4s. 7d. a year! During the seven years ending with 1748 they amounted to only $188,176 16s. 4d: When it is borne in mind that these exports included the military stores of all sorts forwarded to the company's settlements in India and at St. Helena, the amount of which was at all times very considerable, it does appear exceedingly doubtful whether the company really exported, during the entire period from 1730 to 1748, £150,000 worth of British produce as a legitimate mercantile adventure! Their trade, such as it was, was entirely carried on by shipments of bullion; and even its annual average export, during the seven years ending with 1748, only amounted to £548,711 19s. 2d. It would seem, indeed, that the company had derived no perceptible advantage from the important concessions obtained from the Mogul emperor in 1717. But the true conclusion is, not that these concessions were of little value, but that the deadening influence of monopoly had so paralyzed the company that they were unable to turn them to account; and that, though without competitors, and with opulent kingdoms for their customers, their commerce was hardly greater than that carried on by some single merchants.

—In 1732 the company were obliged to reduce their dividend from 8 to 7 per cent, at which rate it continued till 1744.

—The opposition the company had experienced from the merchants when the question as to the renewal of their charter was agitated in 1730 made them very desirous to obtain the next renewal in as quiet a manner as possible. They therefore proposed, in 1743, when twenty-three years of their charter were yet unexpired, to lead £1,000,000 to government, at 3 per cent., provided their exclusive privileges were extended to 1780, with the usual notice; and, as none were expecting such an application, or prepared to oppose it, the consent of the government was obtained without difficulty.

—But the period was now come when the mercantile character of the East India company—if, indeed, it could with propriety be at any time said to belong to them—was to be eclipsed by their achievements as a military power, and the magnitude of their conquests. For about two centuries after the European powers began their intercourse with India, the Mogul princes were regarded as among the most opulent and powerful of monarchs. Though of a foreign lineage—being descended from the famous Tamerlane, or Timur Beg, who overran India in 1400—and of a different religion from the great body of their subjects, their dominion was firmly established in every part of their extensive empire. The administration of the different provinces was committed to officers, denominated soubahdars, or nabobs, intrusted with powers, in their respective governments, similar to those enjoyed by the Roman prætors. So long as the emperors retained any considerable portion of the vigor and bravery of their hardy ancestors, the different parts of the government were held in due subordination, and the soubahdars yielded a ready obedience to the orders from Delhi. But the emperors were gradually debauched by the apparently prosperous condition of their affairs. Instead of being educated in the council or the camp, the heirs of almost unbounded power were brought up in the slothful luxury of the seraglio; ignorant of public affairs; benumbed by indolence; depraved by the flattery of women, of ennuchs and slaves; their minds contracted with their enjoyments; their inclinations were vilified by their habits; and their government grew as vicious, as corrupt and as worthless as themselves. When the famous Kouli Khan, the usurper of the Persian throne, invaded India, the effeminate successor of Tamerlane and Aurengzebe was too unprepared to oppose, and too dastardly to think of avenging, the attack. This was the signal for the dismemberment of the monarchy. No sooner had the invader withdrawn than the soubahdars either openly threw off their allegiance to the emperor, or paid only a species of nominal or mock deference to his orders. The independence of the soubahdars was very soon followed by wars among themselves; and, being well aware of the superiority of European troops and tactics, they anxiously courted the alliance and support of the French and English East India companies. These bodies, having espoused different sides, according as their interests or prejudices dictated, began very soon to turn the quarrels of the soubahdars to their own account. Instead of being contented, as hitherto, with the possession of factories and trading towns, they aspired to the dominion of provinces; and the struggle soon came to be, not which of the native princes should prevail, but whether the English or the French should become the umpires of India.

—But these transactions are altogether foreign to the subject of this work; nor could any intelligible account of them be given without entering into lengthened statements. We shall only, therefore, observe that the affairs of the French were ably conducted by La Bourdonnais, Dupleix and Lally, officers of distinguished merit, and not less celebrated for their great actions than for the base ingratitude of which they were the victims. But though victory seemed at first to incline to the French and their allies, the English affairs were effectually retrieved by the extraordinary talents and address of a single individual. Colonel (afterward Lord) Clive was equally brave, cautions and enterprising; not scrupulous in the use of means; fertile in expedients; endowed with wonderful sagacity and resolution; and capable of turning even the most apparently adverse circumstances to advantage. Having succeeded in humbling the French power in the vicinity of Madras. Clive landed at Calcutta in 1757, in order to chastise Edition: current; Page: [11] the soubdahdar, Surajah ul Dowlah, who had a short while before attacked the English factory at that place, and inhumanly shut up 146 Englishmen in a prison, where, owing to the excessive heat and want of water, 123 perished in a single night. Clive had only 700 European troops and 1,400 Sepoys with him when he landed; but with these, and 570 sailors furnished by the fleet, he did not hesitate to attack the immense army commanded by the soubahdar, and totally defeated him in the famous battle of Plassey. This victory threw the whole provinces of Bengal, Bahar and Orissa into the hands of the English, and they were finally confirmed to them by the treaty negotiated in 1765.

—Opinion has been long divided as to the policy of English military operations in India; and it has been strenuously contended that England should never have extended its conquests beyond the limits of Bengal. The legislature seems to have taken this view of the matter; the house of commons having resolved, in 1782, "that to pursue schemes of conquest and extent of dominion in India are measures repugnant to the wish, the honor and the policy of this nation." But others have argued, and apparently on pretty good grounds, that, having gone thus far, England was compelled to advance. The native powers, trembling at the increase of British dominion, endeavored, when too late, to make head against the growing evil. In this view they entered into combinations and wars against the English; and the latter having been uniformly victorious, their empire necessarily went on increasing, till all the native powers have been swallowed up in its vast extent.

—The magnitude of the acquisitions made by Lord Clive powerfully excited the attention of the British public. Their value was prodigiously exaggerated; and it was generally admitted that the company had no legal claim to enjoy, during the whole period of their charter, all the advantages resulting from conquests to which the fleets and armies of the state had largely contributed. In 1767 the subject was taken up by the house of commons; and a committee was appointed to investigate the whole circumstances of the case, and to calculate the entire expenditure incurred by the public on the company's account. During the agitation of this matter the right of the company to the new conquests was totally denied by several members. In the end, however, the question was compromised by the company agreeing to pay £400,000 a year for two years; and in 1769 this agreement, including the yearly payment, was further extended for five years more. The company at the same time increased their dividend, which had been fixed by the former agreement at 10, to 12½ per cent.

—But the company's anticipations of increased revenue proved entirely visionary. The rapidity of their conquests in India, the distance of the controlling authority at home, and the abuses in the government of the native princes, to whom the company had succeeded, conspired to foster a strong spirit of peculation among their servants. Abuses of every sort were multiplied to a frightful extent. The English, having obtained, or rather enforced, an exemption from those heavy transit duties to which the native traders were subject, engrossed the whole internal trade of the country. They even went so far as to decide what quantity of goods each manufacturer should deliver, and what he should receive for them. It is due to the directors to say that they exerted themselves to repress these abuses; but their resolutions were neither carried into effect by their servants in India, nor sanctioned by the proprietors at home; so that the abuses, instead of being repressed, went on acquiring fresh strength and virulence. The resources of the country were rapidly impaired; and while many of the company's servants returned to Europe with immense fortunes, the company itself was involved in debt and difficulties; and so far from being able to pay the stipulated sum of £400,000 a year to government, was compelled to apply in 1772 to the treasury for a loan!

—In this crisis of their affairs government interposed, and a considerable change was made in the constitution of the company. The dividend was restricted to 6 per cent, till the sum of £1,400,000, advanced to them by the public, should be paid. It was further enacted that the court of directors should be elected for four years, six members annually, but none to hold their seats for more than four years at a time; that no person was to vote at the courts of proprietors who had not possessed his stock for twelve months; and that the amount of stock required to qualify for a vote should be increased from £500 to £1,000. The jurisdiction of the mayor's court at Calcutta was in future confined to small mercantile cases; and, in lieu of it, a new court was appointed, consisting of a chief justice and three principal judges appointed by the crown. A superiority was also given to Bengal over the other presidencies. Mr. Warren Hastings being named in the act as governor general of India. The governor general, councilors and judges were prohibited from having any concern whatever in trade; and no person residing in the company's settlements was allowed to take more than 12 per cent. per annum for money. Though strenuously opposed, these measures were carried by a large majority.

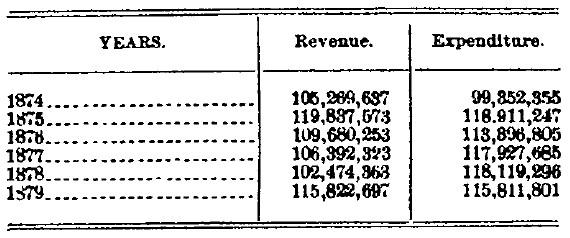

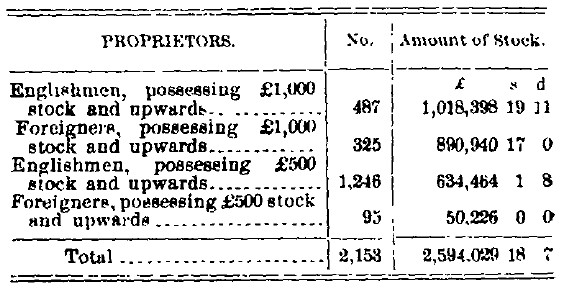

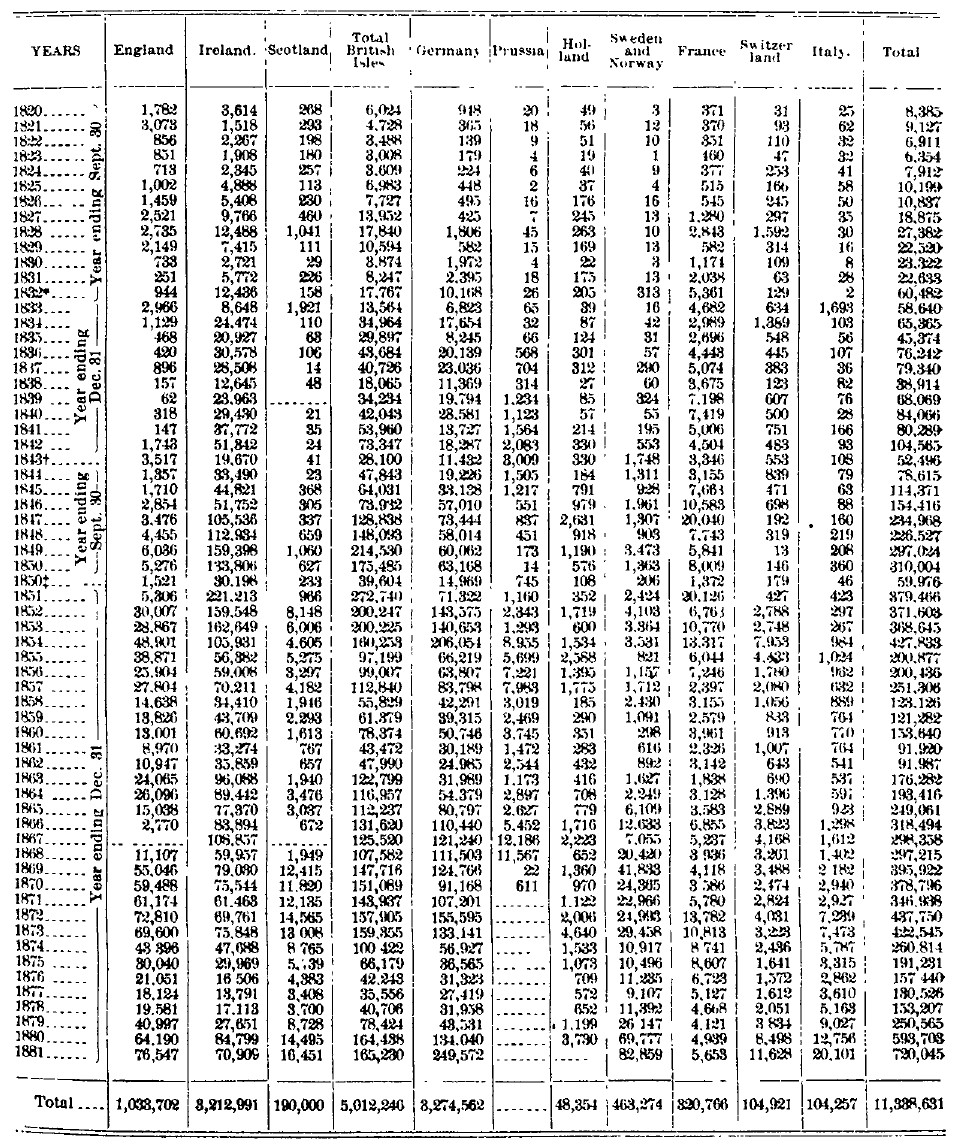

—At this period (1773) the total number of proprietors of East India stock, with their qualifications as they stood in the company's book, were as follows:

—Notwithstanding the vast extension of the company's territories, their trade continued to be apparently insignificant. During the three years ending with 1773 the value of the entire exports of British produce and manufactures, including military stores, sent out by the company to Ind a and China, amounted to £1,469,411, being at the rate of £489,803 a year; the annual exports of bullion during the same period being only £84,9334 During the same three years twenty-three ships sailed annually for India. The truth, indeed, seems to be, that, but for the increased consumption of tea in Great Britain, the company would have entirely ceased to carry on any branch of trade with the east, and that the monopoly would have excluded the English as effectually from the markets of India and China as if the trade had reverted to its ancient channels, and the route by the cape of Good Hope been relinquished.

—In 1781 the exclusive privileges of the company were extended to 1791, with three years' notice; the dividend on the company's stock was fixed at 8 per cent.; three-fourths of their surplus revenues, after paying the dividend and the sum of £400,000 payable to government, was to be applied to the public service, and the remaining fourth to the company's own use.

—In 1780 the value of British produce and manufactures exported by the company to India and China amounted to only £386,152; the bullion exported during the same year was £15,014. The total value of the exports during the same year was £12,648,616; showing that the East India trade formed only one thirty-second part of the entire foreign trade of the empire.

—The administration of Mr. Hastings was one continued scene of war, negotiation and intrigue. The state of the country, instead of being improved, became worse; so much so, that in a council minute by Marquis Cornwallis, dated Sept. 18, 1789, it is distinctly stated "that one-third part of the company's territory is now a jungle for wild beasts." Some abuses in the conduct of their servants were, indeed, rectified; but, notwithstanding, the net revenue of Bengal. Bahar and Orissa, which in 1772 had amounted to £2,126,766, declined in 1785 to £2,072,963. This exhaustion of the country, and the expenses incurred in the war with Hyder Ally and France, involved the company in fresh difficulties; and being unable to meet them, they were obliged in 1783 to present a petition to parliament, setting forth their inability to pay the stipulated sum of £400,000 a year to the public, and praying to be excused from that payment and to be supported by a loan of £900,000.

—All parties seemed now to be convinced that some further changes in the constitution of the company had become indispensable. In this crisis Mr. Fox brought forward his famous India bill, the grand object of which was to abolish the courts of directors and proprietors, and to vest the government of India in the hands of seven commissioners appointed by parliament. The coalition between Lord North and Mr. Fox having rendered the ministry exceedingly unpopular, advantage was taken of the circumstance to raise an extraordinary clamor against the bill. The East India company stigmatized it as an invasion of their chartered rights; though it is obvious that, from their inability to carry into effect the stipulations under which those rights were conceded to them, they necessarily reverted to the public; and it was as open to parliament to legislate upon them as upon any other question. The political opponent of the government represented the proposal for vesting the nomination of commissioners in the legislature as a daring invasion of the prerogative of the crown, and an insidious attempt of the minister to render himself all-powerful by adding the patronage of India to that already in his possession. The bill was, however, carried through the house of commons; but, in consequence of the ferment it had excited, and the avowed opposition of his majesty, it was thrown out in the house of lords. This event proved fatal to the coalition ministry. A new one was formed, with Mr Pitt at its head; and parliament being soon after dissolved, the new minister acquired a decisive majority in both houses. When thus secure of parliamentary support, Mr. Pitt brought forward his India bill, which was successfully carried through all its stages. By this bill a board of control was erected, consisting of six members of the privy council, who were "to check, superintend and control all acts, operations and concerns which in anywise relate to the civil or military government or revenues of the territories and possessions of the East India company." All communications to or from India, touching any of the above matters, were to be submitted to this board, the directors being ordered to yield obedience to its commands, and to alter or amend all instructions sent to India as directed by it. A secret committee of three directors was formed, with which the board of control might transact any business it did not choose to submit to the court of directors. Persons returning from India were to be obliged, under very severe penalties, to declare the amount of their fortunes; and a tribunal was appointed for the trial of all individuals accused of misconduct in India, consisting of a judge from each of the courts of king's bench, common pleas and exchequer; five members of the house of lords, and seven members of the house of commons; the last being chosen by lot at the commencement of each session. The superintendence of all commercial matters continued, as formerly, in the hands of the directors.

—During the administration of Marquis Cornwallis, who succeeded Mr. Hastings, Tippoo Saib, the son of Hyder Ally, was stripped of nearly half of his dominions; the company's territorial revenue was, in consequence, greatly increased; at the same time that the permanent settlement was carried into effect in Bengal, and other important changes accomplished. Opinion has been long divided as to the influence of these changes. On Edition: current; Page: [13] the whole, however, we are inclined to think that they have been decidedly advantageous. Lord Cornwallis was, beyond all question, a sincere friend to the people of India, and labored earnestly, if not always successfully, to promote their interests, which he well knew were identified with those of the British nation.

—During the three years ending with 1793 the value of the company's exports of British produce and manufactures fluctuated from £928,783 to £1,031,262. But this increase is wholly to be ascribed to the reduction of the duty on tea in 1784, and the vast increase that consequently took pace in its consumption. Had the consumption of tea continued stationary, there appear no grounds for thinking that the company's exports in 1793 would have been greater than in 1780, unless an increase had taken place in the quantity of military stores exported.

—In 1793 the company's charter was prolonged till March 1,1814. In the act for this purpose a species of provision was made for opening the trade to India to private individuals. All his majesty's subjects residing in any part of his European dominions were allowed to export to India any article of the produce or manufacture of the British dominions, except military stores, ammunition, masts, spars, cordage, pitch, tar and copper; and the company's civil servants in India, and the free merchants resident there, were allowed to ship, on their own account and risk, all kinds of Indian goods, except calicoes, dimities, muslins, and other piece goods. But neither the merchants in England, nor the company's servants and merchants in India, were allowed to export or import except in the company's ships. And in order to insure such conveyance, it was enacted that the company should annually appropriate 3,000 tons of shipping for the use of private traders; it being stipulated that they were to pay in time of peace £5 outwards, and £15 homewards, for every ton occupied by them in the company's ships; and that this freight might be raised in time of war with the approbation of the board of control.

—It might have been, and indeed most probably was, foreseen that very few British merchants or manufacturers would be inclined to avail themselves of the privilege of sending out goods in company's ships, or of engaging in a trade fettered on all sides by the jealousy of powerful monopolists, and where consequently their superior judgment and economy would have availed almost nothing. As far, therefore, as they were concerned, the relaxation was more apparent than real, and did not produce any useful results. (In a letter to the East India company, dated March 21, 1812, Lord Melville says: "It will not be denied that the facilities granted by that act [the act of 1793] have not been satisfactory, at least to the merchants either of this country or of India. They have been the source of constant dispute, and they have even entailed a heavy expense upon the company, without affording to the public any adequate benefit from such a sacrifice." Papers published by East India Company, 1813, p. 84.) It was, however, made use of to a considerable extent by private merchants in India, and also by the company's servants returning from India, many of whom invested a part and some the whole of their fortune in produce fit for the European markets.

—The financial difficulties of the East India company led to the revolution which took place in its government in 1784. But notwithstanding the superintendence of the board of control, its finances have continued nearly in the same unprosperous state as before. We have been favored from time to time with the most dazzling accounts of revenue that was to be immediately derived from India; and numberless acts of parliament have been passed for the appropriation of surpluses that never had any existence except in the imagination of their framers. The proceedings that took place at the renewal of the charter in 1793 afford a striking example of this. Lord Cornwallis had then concluded the war with Tippoo Saib, which had stripped him of half of his dominions; the perpetual settlement, from which so many benefits were expected to be derived, had been adopted in Bengal; and the company's receipts had been increased, in consequence of accessions to their territory, and subsidies from native princes, etc, to upwards of eight millions sterling a year, which it was calculated would afford a future annual surplus, after every description of charge had been deducted, of £1,240,000. Mr. Dundas (afterward Lord Melville), then president of the board of control, availed himself of these favorable appearances to give the most flattering representation of the company's affairs. There could, he said, be no question as to the permanent and regular increase of the company's surplus revenue; he assured the house that the estimates had been framed with the greatest care; that the company's possessions were in a state of prosperity till then unknown in India; that the abuses which had formerly insinuated themselves into some departments of the government had been rooted out, and that the period had at length arrived when India was to pour her golden treasures into the lap of England! Parliament participated in these brilliant anticipations, and in the act prolonging the charter it was enacted, 1. That £500,000 a year of the surplus revenue should be set aside for reducing the company's debt in India to £2,000,000; 2 That £500,000 a year should be paid into the exchequer, to be appropriated for the public service as parliament should think fit to order; 3. When the India debt should be reduced to £2,000,000, and the bond debt to £1,500,000, one-sixth part of the surplus was to be applied to augment the dividends, and the other five-sixths were to be paid into the bank, in the name of the commissioners of the national debt, to be accumulated as a guarantee fund, until it amounted to £12,000,000; and when it reached that sum, the dividends upon it were to be applied to make up the dividends on the capital stock of the company to 10 Edition: current; Page: [14] per cent., if at any time the funds appropriated to that purpose should prove deficient, etc.

—Not one of these anticipations was realized! Instead of being diminished, the company's debts began immediately to increase. In 1795 they were authorized to add to the amount of their floating debt. In 1796 a new device to obtain money was fallen upon. Mr. Dundas represented that as all competition had been destroyed in consequence of the war, the company's commerce had been greatly increased, and that their mercantile capital had become insufficient for the extent of their transactions. In consequence of this representation, leave was given to the company to add two millions to their capital stock by creating 20,000 new shares; but as these shares sold at the rate of £173 each, they produced £3,460,000. In 1797 the company issued additional bonds to the extent of £1,417,000; and notwithstanding all this, Mr. Dundas stated in the house of commons, March 13,1799, that there had been a deficit in the previous year of £1,319,000.

—During the administration of the Marquis Wellesley, which began in 1797-8 and terminated in 1805-6, the British empire in India was augmented by the conquest of Seringapatam and the whole territories of Tippoo Saib, the cession of large tracts by the Mahratta chiefs, the capture of Delhi, the ancient seat of the Mogul empire, and various other important acquisitions; so that the revenue, which had amounted to £8,039,000 in 1797, was increased to £15,403,000 in 1805. But the expenses of government and the interest of the debt increased in a still greater proportion than the revenue, having amounted in 1805 to £17,672,000, leaving a deficit of £2,269,000. In the following year the revenue fell off nearly £1,000,000, while the expenses continued nearly the same; and there was, at an average, a continued excess of expenditure, including commercial charges, and a contraction of fresh debt, down to 1811-12.

—Notwithstanding the vast additions made to their territories, the company's commerce with them continued to be very inconsiderable. During the five years ending with 1811 the exports to India by the company, exclusive of those made on account of individuals in their ships, were as follows; 1807, £952,416; 1808, £919,544; 1809, £866,153; 1810, £1,010,815; 1811, £1,033,816. The exports by the private trade, and the privilege trade, that is, the commanders and officers of the company's ships, during the above-mentioned years, were about as large. During the five years ending with 1807-8 the annual average imports into India by British private traders, only amounted to £305,496. (Papers, published by the East India company in 1813, 4to, p. 56.) The company's exports included the value of the military stores sent from Great Britain to India. The ships employed in the trade to India and China during the same five years varied from 44 to 53, and their burden from 36,671 to 45,342 tons.